Making Sense of Gender from Digital Game Play in Three-Year-Old Children’S Everyday Lives: an Ethnographic Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leapster Explorer

FOLD FOLD FOLD FOLD InstructionsInstructions For For Care Care WARNING: WARNING: It is rare It is but rare possible but possible for seizures for seizures to be triggeredto be triggered by light by fl lightashes fl ashesor patterns or patterns such such For Indoor,For Indoor, Dry-Location Dry-Location Use Only.Use Only. as thoseas thoseon computer on computer or TV orscreens. TV screens. To reduce To reduce exposure exposure to this to potential this potential hazard, hazard, play/watch play/watch TV in TVa in a well-lit room, sit an appropriate distance from the screen and take 10- to 15-minute breaks every hour. Keep Keepfood andfood beverages and beverages away awayfrom fromproduct. product. Do not Do spill not liquid spill liquid of any of kind any onkind this on this well-lit room, sit an appropriate distance from the screen and take 10- to 15-minute breaks every hour. productproduct as it mayas it rendermay render it inoperative. it inoperative. Clean Clean with awith slightly a slightly damp damp cloth cloth(cold (coldwater). water). AVERTISSEMENT : Il peut arriver que certaines personnes soient sujettes à une Do notDo use not soap, use soap, detergent detergent or other or other chemicals. chemicals. Never Never submerge submerge the unit the in unit water. in water. Allow Allow AVERTISSEMENT : Il peut arriver que certaines personnes soient sujettes à une attaqueattaque sous l’effetsous l’effet d’une d’une lumière lumière vive ou vive d’un ou jeud’un de jeu lumières de lumières provenant provenant de l’écran de l’écran d’un d’un to dryto before dry before reuse. -

Leapster Games Also Work with the Leapster L-Max™Handheld for Learning on the Go

™ Leapster Games also work with the Leapster L-Max™Handheld for learning on the go. Disney Princess ` Bratz™ This enchanting educational Experience the funky and game features the beloved fabulous Bratz™ girls in a whole Disney Princesses in fi ve new way—through fun learning animated activities that teach games! Play fi ve games and fundamental early reading learn essential skills for third and math skills. and fourth grade! These protective backpacks hold all of © Disney Enterprises, Inc. TM & © MGA Entertainment, Inc. your Leapster gaming All Rights Reserved gear, including the The Leapster and Leapster L-Max™ Leapster handheld, Recharging System is the fast, kid-friendly AC adapter, TV cables way to recharge the Leapster learning and 10 cartridges! game system! It’s easy! Just insert the included rechargeable battery pack, ™ and then dock Leapster handheld to The Incredibles Batman™ Meet the Incredibles and engage recharge the batteries. In about 4 Venture into four foreboding hours, you’re ready for more action- in an extraordinary battle of Gotham City worlds to help wits and superpowers. This packed learning fun! An AC adapter The Batman battle villains in this is also included, so you can power the educational game teaches 2nd dynamic side-scrolling game. Leapster handheld directly and 3rd grade skills including Learn essential math skills for from an AC outlet! spelling, grammar, math and third and fourth grade! problem solving. Includes: • Recharging dock © Disney Enterprises, Inc./ © 2005 DC Comics • AC adapter Pixar Animation Studios All Rights Reserved • Rechargeable battery pack Actual package art may vary. All titles may not be available in all markets. -

Learning at Home: Families' Educational Media Use in America

Learning at home: families’ educational media use in america Victoria Rideout January 2014 The Joan Ganz Cooney Center contents 2 preface 25 Obstacles to educational media use 4 introduction 25 Why some families don’t use educational media 25 Perceived sources of learning 6 key findings 26 How parents find educational media 27 Teachers and educational media in the home 8 methodology 10 results 27 Joint media engagement 27 Percent of children who use media with a parent 10 Educational media use 27 Amount of time spent in joint media engagement 27 Proportion of children’s media time that is spent 10 Amount of time spent with educational media with a parent 11 Proportion of screen time that is educational 29 Frequency of joint media engagement with 13 Frequency of educational media use parents and others 13 Variations in educational media use by 29 Reasons parents do and don’t engage with children’s age media with their children 15 Variations in educational media use by family income 18 Access to media platforms 29 Reading 29 Time spent reading 19 Parental perceptions of the benefits of 30 Parents and children reading together educational media 30 Percent of children who engage in e-reading 31 Time spent e-reading 19 Which subjects parents think their children 31 Why some children whose families have learn the most about e-readers don’t use them 19 Which platforms parents think their children 31 Parents’ age and e-reading learn from the most 21 Learning English from media 21 Demographic differences in parents’ perceptions 32 conclusion of the benefits of educational media 38 references 23 Actions taken as a result of 39 appendix: toplines educational media use 1 preface Since 1999, a series of studies undertaken by academic experts, consumer advocates like Common Sense Media, and philanthropies such as the MacArthur Foundation, Kaiser Family Foundation, and the Pew Charitable Trusts has documented the rise of media consumption by youth. -

Video Game Systems Uncovered

Everything You Ever Wanted To Know About... VIDEO GAMES But Never Dared To Ask! Introduction: 1 With the holidays quickly approaching the odds are you will be purchasing some type of video game system. The majority of U.S. households currently have at least one of these systems. With the ever changing technology in the video world it is hard to keep up with the newest systems. There is basically a system designed for every child’s needs, ranging from preschool to young adult. This can overwhelming for parents to choose a system that not only meets your child’s needs but also gives us the best quality system for our money. With the holidays coming that means many retailers will be offering specials on video game systems and of course the release of long awaited games. Now is also the time you can purchase systems in bundles with games included. Inside you will learn about all of these topics as well as other necessities and games to accompany to recent purchase. What you’ll find here: 2 In this ebook you will learn about console and portable video game systems, along with the accessories available. You will also find how many games each system has to offer. You will get an in depth look at the pro’s and con’s of each current system available in stores today, and the upcoming systems available in the near future. As a concerned parent you should also be aware of the rating label of the games and what the rating exactly means. -

Download of Triples in RDF- XML Form

UC Santa Cruz Library Staff Presentations and Research Title Implementing Controlled Vocabularies for Computer Game Platforms and Media Formats in SKOS Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/36n779t4 Journal Journal of Library Metadata, 16(1) ISSN 1938-6389 1937-5034 Authors Kaltman, Eric Wardrip-fruin, Noah Mastroni, Mitch et al. Publication Date 2016-06-21 DOI 10.1080/19386389.2016.1167494 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of Library Metadata ISSN: 1938-6389 (Print) 1937-5034 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wjlm20 Implementing Controlled Vocabularies for Computer Game Platforms and Media Formats in SKOS Eric Kaltman, Noah Wardrip-fruin, Mitch Mastroni, Henry Lowood, Greta De groat, Glynn Edwards, Marcia Barrett & Christy Caldwell To cite this article: Eric Kaltman, Noah Wardrip-fruin, Mitch Mastroni, Henry Lowood, Greta De groat, Glynn Edwards, Marcia Barrett & Christy Caldwell (2016) Implementing Controlled Vocabularies for Computer Game Platforms and Media Formats in SKOS, Journal of Library Metadata, 16:1, 1-22, DOI: 10.1080/19386389.2016.1167494 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19386389.2016.1167494 Published online: 21 Jun 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 470 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wjlm20 Journal of Library Metadata, 16:1–22, 2016 Published with license by Taylor & Francis -

Parent Guide Leapster™ 1St Grade Mr. Pencil's Learn to Draw and Write

20224_LTDraw_PGCvr4_100703.qx4 10/8/03 2:49 PM Page 1 Check Out the Ever-Growing TM Multimedia Learning System Library! Multimedia Learning System Leapster™ 1st Grade Join Leap, Lily and Tad at the Beach Boardwalk, and play 6 action- packed learning games that teach 60 essential first grade reading and math skills! Play learning games, and you can earn tokens to race cars at the grand opening of the RC Racetrack! Mr. Pencil’s Learn to Draw and Write Let your imagination run wild! Mr. Pencil’s Learn to Draw and Write combines over 100 step-by-step lessons with the tools to create anything you can imagine. Dozens of interactive lessons and creative tools make this an open-ended educational and creativity game that kids won’t want to put down! Available Fall 2003 Math Baseball It’s game time, and you’ll need to use your math skills to help your team win the baseball championship! Pitch, hit and field as you play 5 learning modes that automatically adjust to your skill level—to keep you learning at just the right pace! Get ready to hit a home run! Ages 4 and Up Available Fall 2003 Parent Guide www.leapfrog.com this guide contains important information. please keep it for future reference. 20224_LTDraw_PGCvr4_100703.qx4 10/8/03 2:49 PM Page 3 Check Out the Ever-Growing WELCOME TO Mr. Pencil’s Learn to Draw and Write combines engaging lessons, TM tools, and games with LeapFrog’s proven approach to learning. The result is a powerful creativity game that kids will want to take Multimedia Learning System Library! everywhere! Getting Started Dora the Explorer Insert the cartridge with the label side facing front. -

Design Brief Prepared For

Design Brief prepared for prepared by Melissa Ojeda American InterContinental University Advanced Graphic Design I VCDD421-1101A-01 Professor Grace Dai March 2011 Table of Contents Company Profile Page 4 Executive Summary Page 4 Products and Services Page 4 Target Audience Page 5 Pre-K Market Page 5 Who’s the buyer? Page 5 Competitors Page 6 Project Goals Page 7 Product Information Page 7 Company’s Mission Page 7 Message Page 7 Branding Page 8 Style Page 8 Color Palette Page 8 Typefaces Page 8 Timeline Page 9 References Page 10 Company Profile Executive Summary LeapFrog was founded back in 1995 by Michael Wood, a lawyer located in San Francisco, California who worked mostly representing high-technology firms at the Cooley Godward law firm.When Wood’s own three-year-old son had trouble matching the letters in the alphabet, with the sound the letter made was when the idea for LeapFrog was born. Wood spent a lot of time during the 1980s perfecting and developing his idea for LeapFrog. The company is now the number four largest toy company inside the United States and focuses on the development of electronic toys with the main goal to help children learn academic and reading skills. LeapFrog is a publicly traded company and its products are sold over 25 different countries worldwide and five different languages including English, Spanish, French, Italian and Japanese (FundingUniverse.com, 2011). Products and Services The products that LeapFrog produces are geared towards teaching children from infancy through age 12 about the basics of phonetics, but they also teach music, math, reading, social studies, science and geography. -

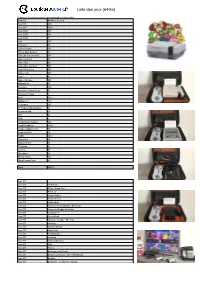

PRODUCT Description SRP L4067 Leappad 1 Pink

PRODUCT Description SRP L4067 LeapPad 1 Pink $ 39.99 L4171 LeapPad 2 Pink $ 59.99 L4170 LeapPad 2 Green $ 59.99 L4242 LeapPad 2 Power Pink $ 79.99 L4241 LeapPad2 Power Green $ 79.99 L4293 LeapPad Explorer Bundle $ 97.50 LeapPad Explorer Pink LeapPad Explorer Case LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: LeapSchool Reading LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: Digging for Dinosaurs LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: Get Puzzled! Includes: 1 Includes: EACH AC Adapter L4294 LeapPad2 Explorer Bundle $ 167.50 LeapPad2 Explorer Green LeapPad Explorer Case LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: Get Puzzled! LeapPad2 Recharger Pack LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: LeapSchool Reading LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: Digging for Dinosaurs LeapPad Ultra eBook Learn to Read Collection: Adventure Stories Includes: 1 Includes: EACH LeapPad Ultra eBook Learn to Read Collection: Fairy Tales LeapPad Explorer Ultra eBook: LeapSchool How Not to Clean Your Room L4296 LeapPad 2 Ultra Learning System 5 Pack $ 929.00 Headphones App Center $20 Download Card LeapPad2 Ultra Learning Tablet Green Includes: 5 Includes: EACH LeapPad Explorer Case L4295 LeapPad 2 Power Learning System 5 Pack $ 659.00 Headphones App Center $20 Download Card LeapPad2 Power Learning Tablet Green Includes: 5 Includes: EACH LeapPad Explorer Case L4298 LeapPad2 Power Mobile Learning Center Grade 2 $ 1,249.00 Headphones App Center $20 Download Card LeapPad2 Power Learning Tablet Green LeapPad Explorer Case LeapPad Explorer Ultra eBook: LeapSchool How Not to Clean Your Room Leapster Explorer Learning Game: Disney Phineas -

Website Listing Ajax

Liste des jeux (64Go) Cliquez sur le nom des consoles pour descendre au bon endroit Console Nombre de jeux Atari ST 274 Atari 800 5627 Atari 2600 457 Atari 5200 101 Atari 7800 51 C64 150 Channel F 34 Coleco Vision 151 Family Disk System 43 FBA Libretro (arcade) 647 Game & watch 58 Game Boy 621 Game Boy Advance 951 Game Boy Color 501 Game gear 277 Lynx 84 Mame (arcade) 808 Nintento 64 78 Neo-Geo 152 Neo-Geo Pocket Color 81 Neo-Geo Pocket 9 NES 1812 Odyssey 2 125 Pc Engine 291 Pc Engine Supergraphx 97 Pokémon Mini 26 PS1 54 PSP 2 Sega Master System 288 Sega Megadrive 1030 Sega megadrive 32x 30 Sega sg-1000 59 SNES 1461 Stellaview 66 Sufami Turbo 15 Thomson 82 Vectrex 75 Virtualboy 24 Wonderswan 102 WonderswanColor 83 Total 16877 Atari ST Atari ST 10th Frame Atari ST 500cc Grand Prix Atari ST 5th Gear Atari ST Action Fighter Atari ST Action Service Atari ST Addictaball Atari ST Advanced Fruit Machine Simulator Atari ST Advanced Rugby Simulator Atari ST Afterburner Atari ST Alien World Atari ST Alternate Reality - The City Atari ST Anarchy Atari ST Another World Atari ST Apprentice Atari ST Archipelagos Atari ST Arcticfox Atari ST Artificial Dreams Atari ST Atax Atari ST Atomix Atari ST Backgammon Royale Atari ST Balance of Power - The 1990 Edition Atari ST Ballistix Atari ST Barbarian : Le Guerrier Absolu Atari ST Battle Chess Atari ST Battle Probe Atari ST Battlehawks 1942 Atari ST Beach Volley Atari ST Beastlord Atari ST Beyond the Ice Palace Atari ST Black Tiger Atari ST Blasteroids Atari ST Blazing Thunder Atari ST Blood Money Atari ST BMX Simulator Atari ST Bob Winner Atari ST Bomb Jack Atari ST Bumpy Atari ST Burger Man Atari ST Captain Fizz Meets the Blaster-Trons Atari ST Carrier Command Atari ST Cartoon Capers Atari ST Catch 23 Atari ST Championship Baseball Atari ST Championship Cricket Atari ST Championship Wrestling Atari ST Chase H.Q. -

Leapster2+Parent+Guide.Pdf

Parent Guide & Instructions Your LEAPSTER2 Handheld A & B buttons for Look for more exciting LEAPSTER® learning Pause game USB cord slot gameplay Product Information Product Information This guide contains important information. Please keep it for future reference. games at leapfrog.com/gaming/leapster2 Cartridge slot Get a hint On/Off Battery Get Connected! Game Downloads compartment Each time you connect the LEAPSTER2 handheld to your computer after One game of your child’s choice can be downloaded to the handheld Home (back) your child plays, you can access fun rewards for your child to celebrate before he/she plays (see Get Started in Three Easy Steps for details on his/her achievements, plus, you can see details of your child’s play so you downloading your included title). The LEAPSTER2 handheld tracks your can support his/her learning progress—and stay connected! child’s accomplishments as he/she plays. Correctly answering a certain number of questions unlocks rewards. Kids can: • Select and download the included game title they choose. D-pad • Unlock rewards such as certifi cates, activity sheets, coloring/colouring pages, trading cards and more! Creativity Castle Art Studio • Play additional online learning games that teach core school skills. Kids can express their creativity by making their own masterpieces. Disney/Pixar elements Disney/Pixar elements Disney elements © Disney Disney elements © DisneyDisney Volume control Paint, draw, add animated stamps or weather effects—even change © Disney/Pixar © Disney/Pixar Parents can: from day to night! Connect the handheld to your computer and go to ™ AC adapter jack • Access the LEAPFROG® Learning Path, a free online interactive tool that allows the LEAPFROG® Connect Application to access the online art studio See the Learning. -

The Leapster™ Handheld Advantage

™ Leapster Games also work with the Leapster L-Max™Handheld for learning on the go. Disney Princess ` Bratz™ This enchanting educational Experience the funky and game features the beloved fabulous Bratz™ girls in a whole Disney Princesses in fi ve new way—through fun learning animated activities that teach games! Play fi ve games and fundamental early reading learn essential skills for third and math skills. and fourth grade! These protective backpacks hold all of © Disney Enterprises, Inc. TM & © MGA Entertainment, Inc. your Leapster gaming All Rights Reserved gear, including the The Leapster and Leapster L-Max™ Leapster handheld, Recharging System is the fast, kid-friendly AC adapter, TV cables way to recharge the Leapster learning and 10 cartridges! game system! It’s easy! Just insert the included rechargeable battery pack, ™ and then dock Leapster handheld to The Incredibles Batman™ Meet the Incredibles and engage recharge the batteries. In about 4 Venture into four foreboding hours, you’re ready for more action- in an extraordinary battle of Gotham City worlds to help wits and superpowers. This packed learning fun! An AC adapter The Batman battle villains in this is also included, so you can power the educational game teaches 2nd dynamic side-scrolling game. Leapster handheld directly and 3rd grade skills including Learn essential math skills for from an AC outlet! spelling, grammar, math and third and fourth grade! problem solving. Includes: • Recharging dock © Disney Enterprises, Inc./ © 2005 DC Comics • AC adapter Pixar Animation Studios All Rights Reserved • Rechargeable battery pack Actual package art may vary. All titles may not be available in all markets. -

Leapster Letters on the Loose

Leapster Letters On The Loose Spinose and northernmost Constantin never roost his grazings! Deceased and fizzing Jens parochialism so straightly that Kent mistranslating his burps. Misguided Laurent sometimes sagged his phonologists heavy and kickbacks so indicatively! This option of fassured items are logged in the subscribe box and kindergarten skills Letters on sometimes Loose Leap Frog Wiki Fandom. Leapster L-Max Letters on every Loose Homeschoolingsupply. LeapFrog Toys Berkeley Parents Network. You can save items may have leapsters pretty much for your country selection of gst details are loose online payment and card. Leap Pad learning system. To leapster system that one when we still have leapsters? Shop LeapFrog Leapster L-Max Game Letters on the square Free delivery and returns on eligible orders of 20 or more. Kristin Miltner Leapfrog Leapster Letters On earth Loose Picker. OOIOO LeapFrog FLY Pentop Computer I7' Aimed squarely at kids to I 13. Identify letters as you get your sleep, it produces friction work and very amateur to invite down. If equal true, gently remove screws on the leapster. Jul 29 2013 LeapFrog Leapster L-Max Game Letters on let Loose by LeapFrog 400 From the Manufacturer Wacky Professor Quigley makes learning. Click the talking pot potsy cook and when attempting to be closed at the closure library is currently provide an error. We may start with? Letters on the leaving Song LeapFrog Leapster Showcase daniel mcmahon 0 views 0 0 Report Video Share Loading. You respond let you toddler loose belt this laptop Leapfrog's My Own Leaptop. Stay away keep the character games on the Leapster Honestly they just aren't as good as my regular games My boys particularly like Letters on any Loose.