Roll of Honour 1914 –18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

ANZAC Day 2015 100Th Anniversary Pilgrimage to Gallipoli School and Youth Group Programme

Cox & Kings Education Travel "Those heroes that shed their blood And lost their lives. You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies And the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side Here in this country of ours. You, the mothers, Who sent their sons from far away countries Wipe away your tears, Your sons are now lying in our bosom And are in peace After having lost their lives on this land they have Become our sons as well." - Kemal Ataturk ANZAC DAY 2015 100th Anniversary Pilgrimage to Gallipoli School and Youth Group programme Cox & Kings Education Travel is proud to offer two very special packages to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the ANZACs’ landing at Gallipoli. The Centenary services are expected to draw the largest crowds ever seen at Gallipoli, so you’ll need to book early to reserve your spot at this truly unforgettable occasion. THE PILGRIMAGE FOR SCHOOL AND YOUTH GROUps One of the aims of our pilgrimage is to provide a deeper understanding of the Gallipoli campaign. Our groups attend services as close to the actual battle sites as possible, and all excursions are accompanied by expert historians who will explain the events that took place a century ago. While the main emphasis is on the contributions of troops from Australia and New Zealand, we will also take time to explore the British, French and Turkish aspects of the campaign. LEGENDS OF GALLIPOLI PILGRIMAGE 8 days/7 nights - Departs 19 April 2015 Day 1 – Sun 19 April: Arrive Istanbul Arrive at Istanbul’s Ataturk Airport and transfer Istanbul to your hotel. -

Drinkerdrinker

FREE DRINKERDRINKER Volume 41 No. 3 June/July 2019 The Anglers, Teddington – see page 38 WETHERSPOON OUR PARTNERSHIP WITH CAMRA All CAMRA members receive £20 worth of 50p vouchers towards the price of one pint of real ale or real cider; visit the camra website for further details: camra.org.uk Check out our international craft brewers’ showcase ales, featuring some of the best brewers from around the world, available in pubs each month. Wetherspoon also supports local brewers, over 450 of which are set up to deliver to their local pubs. We run regular guest ale lists and have over 200 beers available for pubs to order throughout the year; ask at the bar for your favourite. CAMRA ALSO FEATURES 243 WETHERSPOON PUBS IN ITS GOOD BEER GUIDE Editorial London Drinker is published on behalf of the how CAMRA’s national and local Greater London branches of CAMRA, the campaigning can work well together. Of Campaign for Real Ale, and is edited by Tony course we must continue to campaign Hedger. It is printed by Cliffe Enterprise, Eastbourne, BN22 8TR. for pubs but that doesn’t mean that we DRINKERDRINKER can’t have fun while we do it. If at the CAMRA is a not-for-profit company limited by guarantee and registered in England; same time we can raise CAMRA’s profile company no. 1270286. Registered office: as a positive, forward-thinking and fun 230 Hatfield Road, St. Albans, organisation to join, then so much the Hertfordshire AL1 4LW. better. Material for publication, Welcome to a including press The campaign will be officially releases, should preferably be sent by ‘Summer of Pub’ e-mail to [email protected]. -

“Come on Lads”

“COME ON LADS” ON “COME “COME ON LADS” Old Wesley Collegians and the Gallipoli Campaign Philip J Powell Philip J Powell FOREWORD Congratulations, Philip Powell, for producing this short history. It brings to life the experiences of many Old Boys who died at Gallipoli and some who survived, only to be fatally wounded in the trenches or no-man’s land of the western front. Wesley annually honoured these names, even after the Second World War was over. The silence in Adamson Hall as name after name was read aloud, almost like a slow drum beat, is still in the mind, some seventy or more years later. The messages written by these young men, or about them, are evocative. Even the more humdrum and everyday letters capture, above the noise and tension, the courage. It is as if the soldiers, though dead, are alive. Geoffrey Blainey AC (OW1947) Front cover image: Anzac Cove - 1915 Australian War Memorial P10505.001 First published March 2015. This electronic edition updated February 2017. Copyright by Philip J Powell and Wesley College © ISBN: 978-0-646-93777-9 CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................. 2 Map of Gallipoli battlefields ........................................................ 4 The Real Anzacs .......................................................................... 5 Chapter 1. The Landing ............................................................... 6 Chapter 2. Helles and the Second Battle of Krithia ..................... 14 Chapter 3. Stalemate #1 .............................................................. -

West Sussex County Council Designation Full Report 19/09/2018

West Sussex County Council Designation Full Report 19/09/2018 Number of records: 36 Designated Memorials in West Sussex DesigUID: DWS846 Type: Listed Building Status: Active Preferred Ref NHLE UID Volume/Map/Item 297173 1027940 692, 1, 151 Name: 2 STREETLAMPS TO NORTH FLANKING WAR MEMORIAL Grade: II Date Assigned: 07/10/1974 Amended: Revoked: Legal Description 1. 5401 HIGH STREET (Centre Island) 2 streetlamps to north flanking War Memorial TQ 0107 1/151 II 2. Iron: cylindrical posts, fluted, with "Egyptian" capitals and fluted cross bars. Listing NGR: TQ0188107095 Curatorial Notes Type and date: STREET LAMP. Main material: iron Designating Organisation: DCMS Location Grid Reference: TQ 01883 07094 (point) Map sheet: TQ00NW Area (Ha): 0.00 Administrative Areas Civil Parish Arundel, Arun, West Sussex District Arun, West Sussex Postal Addresses High Street, Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9AB Listed Building Addresses Statutory 2 STREETLAMPS TO NORTH FLANKING WAR MEMORIAL Sources List: Department for the Environment (now DCMS). c1946 onward. List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest for Arun: Arundel, Bognor Regis, Littlehampton. Greenbacks. Web Site: English Heritage/Historic England. 2011. The National Heritage List for England. http://www.historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/. Associated Monuments MWS11305 Listed Building: 2 Streetlamps flanking the War Memorial, Arundel Additional Information LBSUID: 297173 List Locality: List Parish: ARUNDEL List District: ARUN List County: WEST SUSSEX Group Value: Upload Date: 28/03/2006 DesigUID: DWS8887 Type: Listed Building Status: Active Preferred Ref NHLE UID Volume/Map/Item 1449028 1449028 Name: Amberley War Memorial DesignationFullRpt Report generated by HBSMR from exeGesIS SDM Ltd Page 1 DesigUID: DWS8887 Name: Amberley War Memorial Grade: II Date Assigned: 24/08/2017 Amended: Revoked: Legal Description SUMMARY OF BUILDING First World War memorial granite cross, 1919, with later additions for Second World War. -

"HERO of the MONTH" LORD ASHCROFT's "HERO of the MONTH" Private Sidney Frank Godley VC Private Sidney Frank Godley VC LORD ASHCROFT's

LORD ASHCROFT'S "HERO OF THE MONTH" LORD ASHCROFT'S "HERO OF THE MONTH" Private Sidney Frank Godley VC Private Sidney Frank Godley VC LORD ASHCROFT'S LEFT: "HERO OF THE MONTH" Private Sidney Frank Godley. Private Sidney Frank Godley VC ABOVE: This bridge at Nimy is a modern replacement for the one on which Lieutenant Maurice Dease and Private Sidney Godley made their stand on 23 August 1914. HE SON of a painter and MAIN PICTURE: officer added an “e” to his family name The Germans later took over the given a civic reception at Lewisham, decorator, Sidney Frank Godley A contemporary of “Godly”. Godley, who had fair hair and hospital and Godley was taken south London (where he lived), 50 T(always known as Frank) was First World a thick moustache, embarked for France prisoner. He refused to answer guineas and a copy of the Lewisham born in East Grinstead, Sussex, on 14 War artist’s and Belgium in August 1914 when his questions but was still well-treated Roll of Honour. August 1889. However, he was largely depiction of battalion was one of the first to go to war. by the Germans, being sent to Berlin There are several memorials in his the action for brought up by an aunt in Willesden, Godley and his comrades arrived at for skin grafts, while his injured back honour and, in 1938, he was presented which Private Middlesex, after his mother died Sidney Godley Mons on 22 August. The next day, during alone required 150 stitches. When he with a special gold medal struck by the when he was six. -

El Vi Naciones Más Igualado

Boletín informativo de la Federación Española de Rugby Boletín Especial VI Naciones 2005 3 de febrero de 2005 Seis Naciones 2005 ¡Vuelve el espectáculo! Federación Española de Rugby La liga “on line”: Tel: 91 541 49 78 / 88 Calle Ferraz, 16 - 4º dcha ℡ 806 517 818 Fax: 91 559 09 86 28008 - MADRID www.ferugby.com [email protected] Boletín Extra VI Naciones 2005 EL VI NACIONES MÁS IGUALADO no han sido nada malos, sólo Australia ha En esta ocasión no se puede decir que conseguido derrotarles, y lo hizo por un haya un equipo a batir. Francia, ajustado 19 a 21. defensora del título, e Inglaterra, único equipo campeón del Mundo de La selección irlandesa ha confirmado su los que participan en el torneo, son candidatura a la lucha por ganar el 6 Naciones. Unos muy buenos resultados en sus los favoritos. Pero las lesiones y los enfrentamientos internacionales así lo resultados cosechados por ambos confirman con victorias sobre Sudáfrica, EEUU. equipos unidos al buen momento de y Argentina. El quince del trébol vive buenos Irlanda y Gales hacen presagiar el 6 momentos y espera confirmarlo en esta edición Naciones más igualado de los últimos del clásico torneo. años. Otro equipo a tener en cuenta en esta edición es el de Gales que ha resuelto sus partidos internacionales muy correctamente. Plantó cara a Nueva Zelanda que sólo logró ganarles de un punto, lo mismo le ocurrió a Sudáfrica que lo hizo por dos puntos. Estos ajustados resultados junto con sus holgadas victorias frente a selecciones como Rumania y Japón hacen que haya que tener muy en cuenta a una selección en auge. -

Rory Underwood's

Rugby legend and ex-RAF pilot Rory Underwood’s top tips on how to get your civilian career off to a flying start By Laura Joint for Equipped Magazine England’s record try scorer Rory Underwood MBE is a perfect example of how it’s possible to achieve success at the highest level in completely different environments. The former Leicester, Bedford, England and British & Irish Lions winger was an RAF pilot throughout his rugby years and successfully adapted his skills – such as teamwork and decision-making – so that they were equally effective whether on a rugby field or in an RAF jet. Rory has now transferred his skills to business, as boss of his performance consultancy firm, Wingman, based in Grantham. So he’s well placed when it comes to offering guidance on how to use and build your skillset, whatever the arena. The arena most of us associate Rory with, of course, is Twickenham. His 85 England caps spanned 12 years from 1984-1996. His debut, as a 20-year-old against Ireland, came only a year after his first game for Leicester – a club he was to play for until 1997. His international career also included all six British & Irish Lions Tests in the two tours to Australia and New Zealand in 1989 and 1993. In his 85 appearances for England he scored 49 tries – an England record that’s unlikely to be broken soon, if ever: “I can’t see it being broken in the near future,” Rory told Equipped. “There’s nobody currently playing who is anywhere near even second place in the list (Will Greenwood and Ben Cohen share second spot with 31 tries). -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

Titles Ordered August 12 - 19, 2016

Titles ordered August 12 - 19, 2016 Audiobook New Adult Audiobook Release Date: Kingsbury, Karen. Brush of wings [sound recording] / Karen Kingsbury. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1532910 3/29/2016 Malzieu, Mathias. The Boy With the Cuckoo-Clock Heart [sound http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1532909 3/2/2010 recording] / Mathias Malzieu [translated by Sarah Ardizzone]. Blu-Ray Non-fiction Blu-Ray Release Date: Bonamassa, Joe Live At The Greek Theatre http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1532904 9/23/2016 Book Adult Fiction Release Date: Benjamin, J. M. (Jimmie M.), author. On the run with love / by J.M. Benjamin. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1533079 Cogman, Genevieve, author. The masked city / Genevieve Cogman. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1532892 9/6/2016 Colgan, Jenny, author. The bookshop on the corner : a novel / Jenny Colgan. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1532882 9/20/2016 Jefferies, Dinah, 1948- author. The tea planter's wife / Dinah Jefferies. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1532897 9/13/2016 Malzieu, Mathias. The Boy With the Cuckoo-Clock Heart / Mathias http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1532883 11/29/2011 Malzieu [translated by Sarah Ardizzone]. Mullen, Thomas. Darktown : a novel / Thomas Mullen. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1532884 9/13/2016 Saunders, Kate, 1960- author. The secrets of wishtide : a Laetitia Rodd mystery / http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1532895 9/13/2016 Kate Saunders. Adult Non-Fiction Release Date: Beck, Glenn, author. Liars : how progressives exploit our fears for power http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1532934 8/2/2016 and control / Glenn Beck. De Sena, Joe, 1969- author. -

Page 1 of 31

Date Name Awards Address Comments RN Lt; married Mary Christine Willis (daughter of Admiral Algernon and Olive http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/life/features/friday- 01 May 1942 John Desmond Davey (inscription to Olive Christine Willis) Willis) on 2 Nov 1942 in Simon's Town, people-shaun-davey-29834708.html South Africa. Lt Cdr 18 Jul 1948. VRD 21 Oct 1950. PAGE HEADED GLENCRAGG, GLENCAIRN, SIMONSTOWN, SOUTH AFRICA 34 Thirlemere Avenue, Standish, Wigan, 24 May 1942 Pilot Officer Frederick George Bamber (121134) KIA 22 Aug 1942 Lancashire The Willows, Lakeside Path, Canvey Island, 24 May 1942 Pilot Officer Peter Robert Griffin (116787) Essex Son of Eric E Billington and brother of Frances Margaret, 26 May 1942 Lieut Robert Edward Billington RNVR DSC Wyke End, West Kirby, Wirral, Cheshire who married The Rev Evan Whidden in Hamilton, Ontario on 28 June 1941 26 May 1942 Harold Mervyn Temple Richards RM The Common, Lechlade, Gloucestershire 19 June 1942 Sydney Mons Stock RN 47 Queens Park Parade, Northampton Kinsdale, Hazledean Road, East Croydon, 28 April 1942 Rear-Admiral Peter George La Niece CB, CBE Surrey [HMS Emerald] St Mary's, Dark [Street] 02 July 1942 Lieut [later Commander] Anthony Gerald William Bellars MBE, MID Lane, Plymton, Nr Plymouth [HMS Express] Langdon Green, Parkland No date Lieutenant (E) John James Tayler Grove, Ashford, Middlesex No date John Desmond Davey VRD, RN Pier House, Cultra, Belfast, Northern Ireland 26 June 1942 Paymaster Commander Harold Stanley Parsons Watch OBE 29 Vectis Road, Alverstoke, Hampshire Bluehayes, Gerrards Cross, June-July 1942 Paymaster Lieutenant William Nevill Dashwood Lang RNVR Buckinghamshire Durnton, Dundas Avenue, North Berwick, http://www.chad.co.uk/news/local/tributes-paid-to-surgeon- No date Surgeon Lieutenant Alexander McEwen-Smith MB, ChB, RNVR Scotland 89-1-694569 Bedford House, Farnborough Road, No date Instructor Lieutenant [later Instructor Commander] Henry Festubert Pearce BSc, RN Farnborough, Hampshire OBE (Malaya). -

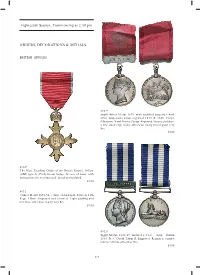

Eighteenth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm ORDERS, DECORATIONS

Eighteenth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm ORDERS, DECORATIONS & MEDALS BRITISH SINGLES 4932* South Africa Medal 1879, with modifi ed suspender with silver suspension clasp engraved 1879 & 1880. Corpl. P.Besserve. Natal Native Contgt. Engraved. Incorrect ribbon, a few small edge nicks, otherwise nicely toned good very fi ne. $200 4930* The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Offi cer (OBE type 2) (Civil) breast badge. In case of issue, with instructions for wearing card, toned uncirculated. $150 4931 Crimea Medal 1854-56, - clasp - Sebastopol. E.Green 11th Regt. 3 Batn. Engraved and renamed. Light scuffi ng and hairlines, otherwise nearly very fi ne. $100 4933* Egypt Medal, 1882-89, undated reverse, - clasp - Suakin 1885. Pte C.Gould T.Supr R. Engraved. Renamed, contact marks in fi elds, otherwise fi ne. $150 418 4934 Khedives Star, 1884-6, reverse impressed Berks 950. Very fi ne. $150 4937* India Medal 1895-1902, (VRI), - two clasps - Relief of Chitral 1895, Tirah 1897-98. Cook Sudh Singh 34th Bl Infy. Engraved in running script. Some contact marks and one 4935* time cleaned, otherwise very fi ne. British South Africa Company's Medal, 1890-97, Rhodesia $120 1896 reverse. Tpr. A.J.Browne. B.S.A.P. Renamed, engraved. Ex Trevor Bushell Taylor Collection. Contact marks, otherwise good very fi ne. $150 Ex M.M.Andrews Collection. 4936 Africa General Service Medal 1902-56, (EVIIR), - clasp - Somaliland 1902-04, Somaliland 1908-10. 175847. F.Hussey, Sto. H.M.S.Fox. Impressed. Hairlines, otherwise good very fi ne. $120 Ex Trevor Bushell Taylor Collection.