The Town of Cēsis from 13Th to 16Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Baltic Vikings - with Particular Consideration to the Ctrronians

East Baltic Vikings - with particular consideration to the Ctrronians Swedish Allies in the Saga World EAST BALTIC At the mythical battlefield of Bravellir (Sw. VIKINGS - WITH Bnl.vallama), Danes and the Swedes clashed in a PARTICULAR fight of epic dimensions. The over-aged Danish king Harald Hildetand finally lost his life, and CONSIDERA his nephew king Sigurdr hringr won Denmark TION TO THE for the Swedes. The story appears in a fragment CURONIANS of a Norse saga from around 1300. But since Sa xo Grammaticus tells it, the written tradition Nils Blornkvist must go back at least to the late 12th century. Wri ting in Latin he prefers to call it bellum Suetici, 'the Swedish war'. It's for several reasons ob vious that Saxo has built his text on a Norse text that must have been quite similar to the preser ved fragment. The battle of Bravellir- the Norse fragment claims - was noteworthy in ancient tales for having be en the greatest, the hardest and the most even and uncertain of the wars that had been fought in the Nordic countries.1 Both sources give long lists of the famous heroes that joined the two armies in a way that recalls the list of ships in Homer's Iliad. These champions are the knight errants of Germanic epics, to some degree rela ted with those of chansons de geste. They are pre sented with characteristic epithets and eponyms that point out their origins in a town, a tribe or a country. When summed up they communicate a geographic vision of the northern World in the 11 th and 12th centuries. -

Tourism Map 2021

Abuls UMURGA VALMIERA CULTURE AND HISTORY 39. EXHIBITION OF RETRO CARS AND HANDICRAFT WORKS. SPULGU VILLAGE OF CEMPMUIŽA THE CONSECRATION OF NEWLYWEDS “Spulgas”, Zosēnu Parish, Jaunpiebalgas County, KAUGURI Pubuļupe Vija 1. ARCHAEOLOGICAL PARK ĀRAIŠI Āraiši, Drabešu Parish, Amatas County, +371 25669935, 26114226, 57.1611, 25.7936 Exhibition of handicraft works from antiquity to the present day. Miegupīte www.araisi.com, 57.2517, 25.2824 Reconstruction of fortified residence of Latgalians in 9th- Masterclasses in embroidery, sewing, and crochet. Possibility to purchase linen products. MŪRMUIŽA Cēsis 10th centuries- lake castle, medieval castle ruins, reconstructions of dwellings from Stone Retro cars, moto ride, a fairy tale forest on the way to the river, view of antshows and a swim RUBENE Kamalda and Bronze Ages. Guide telling stories about the lifestyle of anciens Latgalians and building in the Gauja. Bride and groom’s place of initiation. BRUTUĻI traditions. From 2020, a permanent exhibition can be seen here, in which the original evidence PODZĒNI obtained and the story of archaeologist Jānis Apals can be seen. DAIBE MĀRSNĒNMUIŽA MĒRI surroundingsGROTŪZIS KALNAMUIŽA 2. ĀRAIŠI WINDMILL Āraiši, Drabešu Parish, Amatas County, +371 29238208, 57.2477, Daibes dīķis Sietiņiezis PEŅĢI 25.2712 Built in 1852. In four floors of the mill you can see old mechanisms that grind grain KAIJCIEMS BLOME SMILTENE into flour. By prior appointment groups can have “Miller’s lunch”. Every year in the end of July VAIDAVA Vecpalsa a Day of bread takes place here. Cērtenes pilskalns Sāruma ez. 153 m RAUZA 3. ĀRAIŠI CHURCH Āraiši, Drabešu Par., Amatas Cou., +371 26435206, www.araisudraudze. -

THE DISCOVERY of the BALTIC the NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic C

THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC THE NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD Peoples, Economies and Cultures EDITORS Barbara Crawford (St. Andrews) David Kirby (London) Jon-Vidar Sigurdsson (Oslo) Ingvild Øye (Bergen) Richard W. Unger (Vancouver) Przemyslaw Urbanczyk (Warsaw) VOLUME 15 THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (AD 1075-1225) BY NILS BLOMKVIST BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 On the cover: Knight sitting on a horse, chess piece from mid-13th century, found in Kalmar. SHM inv. nr 1304:1838:139. Neg. nr 345:29. Antikvarisk-topografiska arkivet, the National Heritage Board, Stockholm. Brill Academic Publishers has done its best to establish rights to use of the materials printed herein. Should any other party feel that its rights have been infringed we would be glad to take up contact with them. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blomkvist, Nils. The discovery of the Baltic : the reception of a Catholic world-system in the European north (AD 1075-1225) / by Nils Blomkvist. p. cm. — (The northern world, ISSN 1569-1462 ; v. 15) Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 90-04-14122-7 1. Catholic Church—Baltic Sea Region—History. 2. Church history—Middle Ages, 600-1500. 3. Baltic Sea Region—Church history. I. Title. II. Series. BX1612.B34B56 2004 282’485—dc22 2004054598 ISSN 1569–1462 ISBN 90 04 14122 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

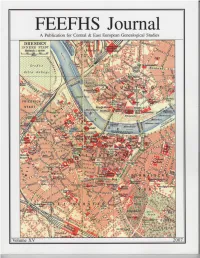

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O. -

Starpkultūru Komunikācijas Barjeras Starp Vāciešiem Un Latvijas Teritorijā Dzīvojošām Maztautām 12

STARPKULTŪRU KOMUNIKĀCIJAS BARJERAS STARP VĀCIEŠIEM UN LATVIJAS TERITORIJĀ DzīVOJOŠĀM MAZTAUTĀM 12. GADSIMTA BEIGĀS UN 13. GADSIMTA SĀKUMĀ PĒC INDRIĶA HRONIKAS UN ATSKAŅU HRONIKAS ZIŅĀM Andris Pētersons Dr. sc. soc., Biznesa augstskolas Turība asociētais profesors. Zinātniskās intereses: komunikācija, komunikācijas vadība, starpkultūru komuni- kācija, komunikācijas vēsture. Raksta mērķis ir ar piemēriem no diviem plašākajiem stāstošās vēstures avotiem par Baltijas tautu cīņām 12. un 13. gadsimtā – Indriķa hronikas un Atskaņu hronikas definēt starpkultūru komunikācijas barjeras starp vācie- šiem un Latvijas teritorijā dzīvojošām maztautām – līviem, letiem, zemga- ļiem, sēļiem un vendiem. (Maztautas tiek sauktas saskaņā ar ābrama Feldhūna tulkojumu Indriķa hronikā.) Komunikācija tiek definēta kā kultū- ras, zināšanu un sociālās uzvedības kodols, bez kuras neviena kultūra nevar pastāvēt. Piemēros no abām hronikām redzamas vāciešu un Latvijas terito- rijā dzīvojošo maztautu vērtības, kā arī viņu atšķirīgās reliģijas, organizē- tības un tehnoloģiju līmeņi, kas bija pamatā starpkultūru komunikācijas barjerām. Vērtības tiek definētas kā kultūras pamats, kultūras dziļākās iz- pausmes, kas ikvienai kultūrai ir atšķirīgas, un kā orientieri, kopējas simbo- liskas sistēmas elementi, kuri kalpo kā kritērijs vai standarts, lai izvēlētos starp iespējamām alternatīvām noteiktā situācijā. Tiek identificētas šādas starpkultūru komunikācijas barjeras: 1) līdzības pieņēmums, ka pamat- vajadzības visiem cilvēkiem ir līdzīgas un pastāv viena, universāla cilvēka daba; 2) valodas atšķirības, ja informācija tiek nodota citā valodā, slengā vai lietojot idiomas; 3) nepareiza neverbālā interpretācija, proti, dažādām kul- tūrām ir dažādas zīmes un signāli; 4) stereotipi un aizspriedumi, kas noved pie vispārinātiem, pastarpinātiem pieņēmumiem; 5) etnocentrisms, kas ir sevis izcelšana, universalizācija un dažādības noliegšana. Jebkurā laikā, pat LATVIJAS VēSTURES INSTITūTA ŽURNāLS ◆ 2016 Nr. 3 (100) 68 Andris Pētersons ilgstoša un nežēlīga kara apstākļos, kādi valdīja Baltijā 12. -

Information for the Repatriates Who Are Third Country Nationals

INFORMATION FOR THE REPATRIATES WHO ARE THIRD COUNTRY NATIONALS This material was prepared during a project Evaluation of the necessities of repatriates who are third-country nationals. The project is coofunded by the European Fund for the Integration of Third Country Nationals. The Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs is fully responsible for the content in this material and the views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the the European Union. CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Needs assessment of repatriated third country nationals............................................................ 6 Examples of repatriates experiences while moving to Latvia..................................................... 7 Latvia ............................................................................................................................................................... 9 • Short history of Latvia ............................................................................................ 9 • Stages of emigration ............................................................................................ 10 • Repatriation – return back to Latvia ................................................................ 11 • National holidays .................................................................................................. 11 • Remembrance and festive -

Musical Practices in the Balkans: Ethnomusicological Perspectives

MUSICAL PRACTICES IN THE BALKANS: ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES МУЗИЧКЕ ПРАКСЕ БАЛКАНА: ЕТНОМУЗИКОЛОШКЕ ПЕРСПЕКТИВЕ СРПСКА АКАДЕМИЈА НАУКА И УМЕТНОСТИ НАУЧНИ СКУПОВИ Књига CXLII ОДЕЉЕЊЕ ЛИКОВНЕ И МУЗИЧКЕ УМЕТНОСТИ Књига 8 МУЗИЧКЕ ПРАКСЕ БАЛКАНА: ЕТНОМУЗИКОЛОШКЕ ПЕРСПЕКТИВЕ ЗБОРНИК РАДОВА СА НАУЧНОГ СКУПА ОДРЖАНОГ ОД 23. ДО 25. НОВЕМБРА 2011. Примљено на X скупу Одељења ликовне и музичке уметности од 14. 12. 2012, на основу реферата академикâ Дејана Деспића и Александра Ломе У р е д н и ц и Академик ДЕЈАН ДЕСПИЋ др ЈЕЛЕНА ЈОВАНОВИЋ др ДАНКА ЛАЈИЋ-МИХАЈЛОВИЋ БЕОГРАД 2012 МУЗИКОЛОШКИ ИНСТИТУТ САНУ SERBIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS ACADEMIC CONFERENCES Volume CXLII DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS AND MUSIC Book 8 MUSICAL PRACTICES IN THE BALKANS: ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE HELD FROM NOVEMBER 23 TO 25, 2011 Accepted at the X meeting of the Department of Fine Arts and Music of 14.12.2012., on the basis of the review presented by Academicians Dejan Despić and Aleksandar Loma E d i t o r s Academician DEJAN DESPIĆ JELENA JOVANOVIĆ, PhD DANKA LAJIĆ-MIHAJLOVIĆ, PhD BELGRADE 2012 INSTITUTE OF MUSICOLOGY Издају Published by Српска академија наука и уметности Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts и and Музиколошки институт САНУ Institute of Musicology SASA Лектор за енглески језик Proof-reader for English Јелена Симоновић-Шиф Jelena Simonović-Schiff Припрема аудио прилога Audio examples prepared by Зоран Јерковић Zoran Jerković Припрема видео прилога Video examples prepared by Милош Рашић Милош Рашић Технички -

Iš Istorijos Ūkų Mėlynuojantys Kuršiai

Iš istorijos ūkų mėlynuojantys kuršiai Apie rekonstruotus I–XIV a. kuršių kostiumus su baltų genčių archeologinio ir istorinio kostiumo atkūrėjomis, projekto vykdytojomis – dizainere konstruktore, LLKC Tautodailės poskyrio vyriausiąja specialiste Danute KETURAKIENE ir archeologe, VšĮ „Vita Antiqua“ direktore dr. Daiva STEPONAVIČIENE, taip pat su lietuvių ir kuršių genčių kostiumų demonstruotojais Dovile KETURAKYTE, Ramune STEPONAVIČIŪTE ir Žygimantu LIAUSA kalbasi Juozas ŠORYS. Tarp audimo staklių ir lekalų teriškų ir keturi vyriškų drabužių komplektai. Į kom- plektą įeina galvos danga, drabužiai, avalynė, ginklai, Kaskart užėjus į LLKC kieme įsikūrusią rekonstruoja- odos galanterija, papuošalai. Beje, ir jau sukurtos (be mų kostiumų būstinę nustebina palei sieną sukabinta minėtų, dar žemaičių ir jotvingių), ir dar planuojamos vilnonių ir kitokių audinių faktūra, spalvų ryškumu išsi- kurti (šiais metais kursime aukštaičių kolekciją – ga- skirianti I–XIV a. kuršių genties archeologinio ir istorinio vome finansavimą) baltų genčių kostiumų kolekcijos kostiumo (su gretimai kybančiomis lietuvių ir kitų bal- (po keturis moterų ir vyrų) bus saugomos LLKC. Šiuos tų genčių kolekcijomis) „apkaba“, ant stalo – neseniai darbus atliekame vykdydami projektus, kuriuos pare- LLKC išleistas 2013/2014 m. kalendorius „Kuršių kostiu- mia Kultūros rėmimo fondas, dalį finansavimo skiria ir mas I–XIV a.“. Kaip užsimezgė šis idėjos aiškumu ir drą- LLKC. Tautinį kostiumą jau esame smulkiai ištyrinėję, sumu savaip unikalus ir skeptikus netgi šokiruojantis išleidome nemažai jam skirtų leidinių, tad dabar su- projektas? Besidominčiuosius archeologinėmis tekstili- sitelkėme ties archeologinio kostiumo atkūrimo dar- nėmis rekonstrukcijomis ypač suintrigavo šie ir ankstes- bais. Juolab kad jo rekostrukcijos Lietuvoje prasidėjo ni originalūs ir dabar tiesiog rankomis apčiuopiami jūsų gana vėlai – mus buvo aplenkusios ne tik Skandinavi- pastangų šioje specifinėje srityje rezultatai. -

12Th Century AD Specific Burial Practices and Artefact Forms Serve To

ENG Ancient Peoples in the Territory of Latvia 1st –12th century AD Specific burial practices and artefact forms serve to distinguish several different archaeological cultures, connected with the ancestors of the Couronians [64–65]*, Latgalians, Selonians and Semigallians [61], and Finnic groups [62,63]. In the Middle Iron Age (400–800 AD) and the first half of the Late Iron Age (800–1 000 AD), the archaeological cultures of the Early Iron Age underwent complicated processes of ethno-cultural change, developing into the Baltic peoples (Couronians, Semigallians, Latgallians and Selonians) and Finnic peoples (Livs, Estonians and Vends) that we know from written sources. In the second half of the Late Iron Age (1 000–1 200 AD) the distinctive culture of Latvia’s indigenous peoples reached its highest point of development. The dead were buried together with a wide range of grave goods. Specific peoples’ territory of residence can be traced by characteristic burial traditions, various forms of ornaments, tools and weapons. The Couronians [66–70] lived along the Baltic littoral of western Latvia and western Lithuania. The Latgallians and Selonians [71–78] inhabited eastern Latvia, the Selonians lived along the left bank of the Daugava and in north-eastern Lithuania, while the Semigallians [79–82] lived in the basin of the River Lielupe, in southern Latvia and northern Lithuania. In the 10th and 11th century in the lower reaches of Daugava and Gauja developed and flourished the culture of the Livs. [83,84]. By the River Ālande, in the Couronian area, a Scandinavian colony existed for two centuries (650–800 AD) [85,86]. -

Donina Et El Burial Practices at Lapiņi Curonian Cremation

84 Archaeologia Baltica 27, 2020, 84-103 BURIAL PRACTICES AT LAPIŅI CURONIAN CREMATION CEMETERY, WEST LATVIA, AT THE CLOSE OF THE IRON AGE AND IN THE MIDDLE AGES (12TH–14TH/15TH CENTURIES) INGA DONIŅA,1,* NORMUNDS STIVRINS, 1,2 VALDIS BĒRZIŅŠ1 1 Latvian Institute of History, University of Latvia, Kalpaka bulvāris 4, LV-1050 Riga, Latvia 2 University of Latvia, Jelgavas iela 1, LV-1004, Riga, Latvia. Tallinn University of Technology, Ehitajate tee 5, EE-19086, Tallinn, Estonia. Lake and Peatland Research Centre, Puikule, Aloja district, Latvia Keywords Abstract Lapiņi cemetery, This article examines cremation cemeteries in west Latvia from the end of the Late Iron Age and cremation burials, the Middle Ages (12th–14th/15th centuries). During this period, cremation graves constituted Curonians, burial ritual, the dominant burial form in the region. We have selected as a case study Lapiņi cemetery, which Late Iron Age, Middle reveals additional details relating to cremation cemeteries of west Latvia. The aim of the article is Ages, non-pollen to provide further insights into burials of this kind in the Baltic region, which correspond in time palynomorphs, pollen, to the Curonian expansion in northwest Latvia, followed by the conquest by the Crusaders and wood charcoal the change of religion and burial practices in present-day Latvia. For a better understanding of the environmental conditions at the time of use of the cemetery, taxonomic analysis has been under- taken of the charcoal used as fuel for cremation, as well as an analysis of pollen and non-pollen palynomorphs from cremation graves. Lapiņi is so far the only Curonian cemetery in present-day Latvia where such analyses have been conducted. -

Preventive Archaeology in Latvia: Example Investigations in the Historical Town Centres on Kuldīga and Ventspils

BADANIA RATOWNICZE ZA GRANICĄ raport 10, 219-231 issn 2300-0511 Sandra Zirne*, Mārtiņš Lūsēns**, Armands Vijups*** Preventive Archaeology in Latvia: example investigations in the historical town centres on Kuldīga and Ventspils Abstract Zirne S., Lūsēns M., Vijups A. 2015. Preventive Archaeology in Latvia: example investigations in the historical town centres on Kuldīga and Ventspils. Raport 10, 219-231 This article deals with preventive archaeology issues in the Republic of Latvia. Legislative bacground provides presence of archaeologists in construction projects. During last decade in the Latvia the largest share of carried out archaeological fieldwork are archaeological supervisions. Despite of small scale rescue excavations and archaeological supervisions significant archaeological data has been collected on further inves- tigations on historical development of ancient towns. As examples are presented the most interesting discoveries in the two towns located in the Western part of the Latvia – Kuldīga and Ventspils. Archaeological investigations of the town streets in Kuldīga, carried out by M. Lūsēns, supplemented the reconstruction and localization of old Kuldīga, mostly based on information found in written sources. Small-scale preven- tive archaeological projects that have taken place in the seaside town Ventspils has resulted in a study of A.Vijups on the impact of dune erosion processes on historical development of town. Keywords: preventive archaeology, supervision, rescue excavations, historical development, dune erosion ■ Introduction The risk of such a situation is that the scientific interests In 2014, ten years had passed since the European of archaeologists become subject to economic factors. Convention on the Protection of Archaeological The development of preventive archaeology in Heritage (Revised), adopted in Valletta (Malta), entered Latvia is closely related to the internal geopolitical situ- into force in the Republic of Latvia. -

Valmiera in the Hanseatic League: Heritage Research

VALMIERA CITY COUNCIL Dr.hist. Ilgvars Misāns VALMIERA IN THE HANSEATIC LEAGUE: HERITAGE RESEARCH Nowadays, most residents of Latvia have positive or at least neutral associations with the name “Hansa”. Hardly anyone is surprised to see this name on signboards of Latvian enterprises, for example, Hansa hotel, bakery, wine gallery or beauty parlour. The name is also used by logistics companies and tile traders, and even by a secondary school located in the centre of Rīga. Additionally, medieval festivals and markets in Latvia are organised under the sign of the Hanseatic League. Rīga and other Latvian towns, such as Cēsis, Koknese, Kuldīga, Limbaţi, Straupe, Valmiera, and Ventspils tend to pride themselves on the participation in the Hanseatic League. In short, people see the name of Hansa a lot, but what do the people who use this name today know about the historical Hanseatic League? 1. HANSEATIC LEAGUE The Earlier and Current Understanding of the Nature of the Hanseatic League A person who is not familiar with scientific literature on medieval history is likely to answer the aforementioned question as follows: a mighty political union of German towns with the goal of ensuring their dominance in trade in the North Sea and Baltic Sea regions using their shared privileges. This explanation was generally accepted for a long time, it is 1 still used in popular publications1 and reference literature2, although recent historical research offers another definition of the Hanseatic League.3 Interpretation of the nature of the Hanseatic League has changed because historians have recently been studying it not only as a participant of political events, but also from the perspective of economic and social history.