Donina Et El Burial Practices at Lapiņi Curonian Cremation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar ) in Subdivisions 22–31 (Baltic

ICES Advice on fishing opportunities, catch, and effort Baltic Sea ecoregion Published 29 May 2020 Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in subdivisions 22–31 (Baltic Sea, excluding the Gulf of Finland) ICES advice on fishing opportunities ICES advises that when the precautionary approach is applied, total commercial sea catch in 2021 should be no more than 116 000 salmon, assuming no change in recreational effort. Applying the same catch proportions estimated from observations in the 2019 fishery, the catch in 2021 would be split as follows: 106 000 salmon projected landings (91%; i.e. 83% reported, 7% unreported, and 1% misreported) and projected discards of 10 000 salmon (9%; previously referred to as discards). This would correspond to commercial landings (the reported projected landings) of 96 600 salmon. ICES advises that management of salmon fisheries should be based on the status of individual river stocks. Fisheries on mixed stocks that encompass weak wild stocks present particular threats, and should be kept as close to zero as possible. Fisheries in open-sea areas or in coastal waters target mixed stocks; they are thus more likely to pose a threat to depleted stocks than fisheries in estuaries and in healthy (at or above MSY) wild or reared salmon rivers. The salmon stocks of rivers Rickleån, Sävarån, Öreälven, and Lögdeälven in the Gulf of Bothnia, Emån in southern Sweden, and all rivers in the southeastern Main Basin (AU 5) are particularly weak, and several have shown limited recovery to previous reductions in exploitation rates at sea. The offshore and coastal fisheries in the Main Basin includes catches from all of these weak salmon stocks on their feeding migration. -

East Baltic Vikings - with Particular Consideration to the Ctrronians

East Baltic Vikings - with particular consideration to the Ctrronians Swedish Allies in the Saga World EAST BALTIC At the mythical battlefield of Bravellir (Sw. VIKINGS - WITH Bnl.vallama), Danes and the Swedes clashed in a PARTICULAR fight of epic dimensions. The over-aged Danish king Harald Hildetand finally lost his life, and CONSIDERA his nephew king Sigurdr hringr won Denmark TION TO THE for the Swedes. The story appears in a fragment CURONIANS of a Norse saga from around 1300. But since Sa xo Grammaticus tells it, the written tradition Nils Blornkvist must go back at least to the late 12th century. Wri ting in Latin he prefers to call it bellum Suetici, 'the Swedish war'. It's for several reasons ob vious that Saxo has built his text on a Norse text that must have been quite similar to the preser ved fragment. The battle of Bravellir- the Norse fragment claims - was noteworthy in ancient tales for having be en the greatest, the hardest and the most even and uncertain of the wars that had been fought in the Nordic countries.1 Both sources give long lists of the famous heroes that joined the two armies in a way that recalls the list of ships in Homer's Iliad. These champions are the knight errants of Germanic epics, to some degree rela ted with those of chansons de geste. They are pre sented with characteristic epithets and eponyms that point out their origins in a town, a tribe or a country. When summed up they communicate a geographic vision of the northern World in the 11 th and 12th centuries. -

Latvia Toponymic Factfile

TOPONYMIC FACT FILE Latvia Country name Latvia State title Republic of Latvia Name of citizen Latvian Official language Latvian (lv) Country name in official language Latvija State title in official language Latvijas Republika Script Roman n/a. Latvian uses the Roman alphabet with three Romanization System diacritics (see page 3). ISO-3166 country code (alpha-2/alpha-3) LV / LVA Capital (English conventional) Riga1 Capital in official language Rīga Population 1.88 million2 Introduction Latvia is the central of the three Baltic States3 in north-eastern Europe on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. It has existed as an independent state c.1918 to 1940 and again since 1990. In size it is similar to Sri Lanka or Sierra Leone. Latvia is approximately 1% smaller than neighbouring Lithuania, but has only two-thirds the population, estimated at 1.88 million in 20202. The population has been falling steadily since a high of 2,660,000 in 1989 source: Eurostat). Geographical names policy Latvian is written in Roman script. PCGN recommends using place names as found on official Latvian-language sources, retaining all diacritical marks. Latvian generic terms frequently appear with lower-case initial letters, and PCGN recommends reflecting this style. Allocation and recording of geographical names in Latvia are the responsibility of the Latvia Geospatial Information Agency (Latvian: Latvijas Ģeotelpiskās informācijas aģentūra – LGIA) which is part of the Ministry of Defence (Aizsardzības ministrija). The geographical names database on the LGIA website: http://map.lgia.gov.lv/index.php?lang=2&cPath=3&txt_id=24 is a useful official source for names. -

Tourism Map 2021

Abuls UMURGA VALMIERA CULTURE AND HISTORY 39. EXHIBITION OF RETRO CARS AND HANDICRAFT WORKS. SPULGU VILLAGE OF CEMPMUIŽA THE CONSECRATION OF NEWLYWEDS “Spulgas”, Zosēnu Parish, Jaunpiebalgas County, KAUGURI Pubuļupe Vija 1. ARCHAEOLOGICAL PARK ĀRAIŠI Āraiši, Drabešu Parish, Amatas County, +371 25669935, 26114226, 57.1611, 25.7936 Exhibition of handicraft works from antiquity to the present day. Miegupīte www.araisi.com, 57.2517, 25.2824 Reconstruction of fortified residence of Latgalians in 9th- Masterclasses in embroidery, sewing, and crochet. Possibility to purchase linen products. MŪRMUIŽA Cēsis 10th centuries- lake castle, medieval castle ruins, reconstructions of dwellings from Stone Retro cars, moto ride, a fairy tale forest on the way to the river, view of antshows and a swim RUBENE Kamalda and Bronze Ages. Guide telling stories about the lifestyle of anciens Latgalians and building in the Gauja. Bride and groom’s place of initiation. BRUTUĻI traditions. From 2020, a permanent exhibition can be seen here, in which the original evidence PODZĒNI obtained and the story of archaeologist Jānis Apals can be seen. DAIBE MĀRSNĒNMUIŽA MĒRI surroundingsGROTŪZIS KALNAMUIŽA 2. ĀRAIŠI WINDMILL Āraiši, Drabešu Parish, Amatas County, +371 29238208, 57.2477, Daibes dīķis Sietiņiezis PEŅĢI 25.2712 Built in 1852. In four floors of the mill you can see old mechanisms that grind grain KAIJCIEMS BLOME SMILTENE into flour. By prior appointment groups can have “Miller’s lunch”. Every year in the end of July VAIDAVA Vecpalsa a Day of bread takes place here. Cērtenes pilskalns Sāruma ez. 153 m RAUZA 3. ĀRAIŠI CHURCH Āraiši, Drabešu Par., Amatas Cou., +371 26435206, www.araisudraudze. -

THE DISCOVERY of the BALTIC the NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic C

THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC THE NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD Peoples, Economies and Cultures EDITORS Barbara Crawford (St. Andrews) David Kirby (London) Jon-Vidar Sigurdsson (Oslo) Ingvild Øye (Bergen) Richard W. Unger (Vancouver) Przemyslaw Urbanczyk (Warsaw) VOLUME 15 THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (AD 1075-1225) BY NILS BLOMKVIST BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 On the cover: Knight sitting on a horse, chess piece from mid-13th century, found in Kalmar. SHM inv. nr 1304:1838:139. Neg. nr 345:29. Antikvarisk-topografiska arkivet, the National Heritage Board, Stockholm. Brill Academic Publishers has done its best to establish rights to use of the materials printed herein. Should any other party feel that its rights have been infringed we would be glad to take up contact with them. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blomkvist, Nils. The discovery of the Baltic : the reception of a Catholic world-system in the European north (AD 1075-1225) / by Nils Blomkvist. p. cm. — (The northern world, ISSN 1569-1462 ; v. 15) Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 90-04-14122-7 1. Catholic Church—Baltic Sea Region—History. 2. Church history—Middle Ages, 600-1500. 3. Baltic Sea Region—Church history. I. Title. II. Series. BX1612.B34B56 2004 282’485—dc22 2004054598 ISSN 1569–1462 ISBN 90 04 14122 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

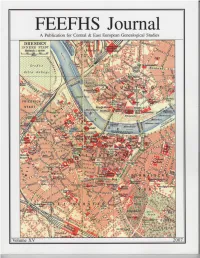

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O. -

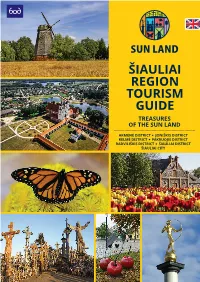

Saules Zemes Turtai EN(6).Pdf

3 SEVEN WONDERS OF THE LAND OF ŠIAULIAI THE HILL OF CROSSES with over 200,000 crosses. Every year, the hill is visited by thousands of tourists from all over the world. SUNDIAL SQUARE with the highest sundial in Lithuania and a gilded sculpture “Šaulys” (“Archer”) that has become the city’s symbol. THE ENSEMBLE OF TYTUVĖNAI CHURCH AND MONASTERY – one of the most interesting and largest examples of Lithuanian sacral architecture, adorned with frescoes, dating back to the 17th-18th centuries. THE BUTTERFLY EXPOSITION – you will find the largest collection of diurnal butterflies in Lithuania in the Akmenė Regional Museum. CHERRIES OF ŽAGARĖ – a four-day cherry festival and the election of the most beautiful scarecrow in one of the most unique Lithuanian towns in Joniškis land. WINDMILLS OF PAKRUOJIS – the wind accelerating in wide plains is turning the vanes of as many as 18 windmills. THE TULIP FLOWERING FESTIVAL – held every spring in the Burbiškis manor, Radviliškis land; as many as half a thousand tulip species burst into flower. 4 4 ŠIAULIAI The centre of the city, which was twice destroyed during the wars of the 20th century and rebuilt again, has distinct architectural heritage of the interwar pe- riod modernism, which has survived to this day. Šiauliai is a city-phoenix, every time rising from ashes. Discover Šiauliai and experience the magic of 3 “S”: sweets, special museums, and the sun. The symbols of the sun, scattered all over the city (sundials, stained glass, etc.), have become an integral part of the city. The oldest sweet factory of Lithuania, “Rūta”, operating for over 100 years, special museums of chocolate, photogra- phy, telephony, and the only such Vanda Kavaliauskienė’s Cats Museum with over 4000 exhibits. -

Ancient Natural Sacred Sites in Kurzeme Region, Latvia

dating back to 1234 about enfeoffing of 25 acres of land 5 to the Riga St. Peter’s Church, was situated. The hill fort IN THE WAKE OF THE CURONIANS was located in the Curonian land of Vanema. The Mežīte Hill Fort was constructed on a solitary, about 13 m high Longer distances of the route are hill, the slopes of which had been artificially made steep- heading along asphalt roads, but 3 The CURONIAN HILL FORT er. Its plateau is of a triangular form, 55 x 30–50 m large, access to ancient cult sites mostly is OF VeCKULDīGA with a narrower southern part, on which a 3 meters high available along gravel and forest roads. Kuldīga 56º59’664 21º57’688 rampart had been heaped up. It used to protect the as- Long before the introduction of Christianity in cent to the hill fort, which, just like in many other Latvian Length of the route 145 km the ancient land of Cursa and expansion of the hill forts, was planned in such a way that when invaders 9 10 22 Livonian Order, on the present site of the hill fort of were striving to conquer the hill fort, their shoulders, Veckuldīga, at the significant waterway of the Venta unprotected by a shield, would be turned against the 21 has been observed: in the nearby trees, there have ancestors’ traditions are still kept alive by celebrating cult tree, its age could be around 400–500 years. River, one of the largest and best fortified castles of hill fort’s defenders. -

Application Form for Listing Under the “European Heritage Label” Scheme

Application form for listing under the “European Heritage Label” scheme Country Latvia Region/province Kurzeme region, Kuldiga city Name of the cultural property1, monument, natural or urban site2, Kuldiga or site that has played a key role in European history. Owner the cultural property, Kuldiga Municipality monument, natural or urban site, or site that has played a key role in European history Public or private authorities Kuldiga Town Council responsible for the site or property (delegated management) Postal address Geographic coordinates Geographical location: Latitude 56°58’03’’; Longitude 21°58’14’’ The property is located in the western part of Latvia, in Kuldiga district, 150 km from Riga, the capital of Latvia. See attached map – appendix nr. 1. Reasons for listing Kuldiga is a little unique old town, which is significant for Preserved town planning of middle age style; Preserved splendid wooden buildings of 17-19 centuries; There is the widest waterfall in all the Europe situated (the width is 249 - 275 m depending from season); The coasts of the riversides are linked with old, one of the longest brick bridges; Since 1368 Kuldiga has been a member of the Hanseatic League; It is the native town of the duke Jacob; In 1595-1618, has been a capital of Kurland. Kuldiga is a province town of the Baltic region where number of unique values is concentrated at one place. There is specific town environment with unrepeatable social life where dominates throw centuries unchanged romantic and intimate spirit. Kuldiga old town fulfils following criteria – site of cultural and historical interest that have particular European significance for Member States in general and urban and natural area, riverside archaeological site. -

Recreational Fishing in the Baltic Sea Region

PROTECTING THE BALTIC SEA ENVIRONMENT - WWW.CCB.SE RECREATIONAL FISHING IN THE BALTIC SEA REGION Coalition Clean Baltic Researched and written by Niki Sporrong for Coalition Clean Baltic E-mail: [email protected] Address: Östra Ågatan 53, 753 22 Uppsala, Sweden www.ccb.se © Coalition Clean Baltic 2017 With the contribution of the LIFE financial instrument of the European Community and the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management Contents Background ...................................................................................................................4 Introduction ..................................................................................................................5 Summary .......................................................................................................................6 Terminology .................................................................................................................12 Finland (not including Åland1) .....................................................................................15 Estonia ..........................................................................................................................23 Latvia ............................................................................................................................32 Lithuania ......................................................................................................................39 Russia (Kaliningrad region) ..........................................................................................45 -

Starpkultūru Komunikācijas Barjeras Starp Vāciešiem Un Latvijas Teritorijā Dzīvojošām Maztautām 12

STARPKULTŪRU KOMUNIKĀCIJAS BARJERAS STARP VĀCIEŠIEM UN LATVIJAS TERITORIJĀ DzīVOJOŠĀM MAZTAUTĀM 12. GADSIMTA BEIGĀS UN 13. GADSIMTA SĀKUMĀ PĒC INDRIĶA HRONIKAS UN ATSKAŅU HRONIKAS ZIŅĀM Andris Pētersons Dr. sc. soc., Biznesa augstskolas Turība asociētais profesors. Zinātniskās intereses: komunikācija, komunikācijas vadība, starpkultūru komuni- kācija, komunikācijas vēsture. Raksta mērķis ir ar piemēriem no diviem plašākajiem stāstošās vēstures avotiem par Baltijas tautu cīņām 12. un 13. gadsimtā – Indriķa hronikas un Atskaņu hronikas definēt starpkultūru komunikācijas barjeras starp vācie- šiem un Latvijas teritorijā dzīvojošām maztautām – līviem, letiem, zemga- ļiem, sēļiem un vendiem. (Maztautas tiek sauktas saskaņā ar ābrama Feldhūna tulkojumu Indriķa hronikā.) Komunikācija tiek definēta kā kultū- ras, zināšanu un sociālās uzvedības kodols, bez kuras neviena kultūra nevar pastāvēt. Piemēros no abām hronikām redzamas vāciešu un Latvijas terito- rijā dzīvojošo maztautu vērtības, kā arī viņu atšķirīgās reliģijas, organizē- tības un tehnoloģiju līmeņi, kas bija pamatā starpkultūru komunikācijas barjerām. Vērtības tiek definētas kā kultūras pamats, kultūras dziļākās iz- pausmes, kas ikvienai kultūrai ir atšķirīgas, un kā orientieri, kopējas simbo- liskas sistēmas elementi, kuri kalpo kā kritērijs vai standarts, lai izvēlētos starp iespējamām alternatīvām noteiktā situācijā. Tiek identificētas šādas starpkultūru komunikācijas barjeras: 1) līdzības pieņēmums, ka pamat- vajadzības visiem cilvēkiem ir līdzīgas un pastāv viena, universāla cilvēka daba; 2) valodas atšķirības, ja informācija tiek nodota citā valodā, slengā vai lietojot idiomas; 3) nepareiza neverbālā interpretācija, proti, dažādām kul- tūrām ir dažādas zīmes un signāli; 4) stereotipi un aizspriedumi, kas noved pie vispārinātiem, pastarpinātiem pieņēmumiem; 5) etnocentrisms, kas ir sevis izcelšana, universalizācija un dažādības noliegšana. Jebkurā laikā, pat LATVIJAS VēSTURES INSTITūTA ŽURNāLS ◆ 2016 Nr. 3 (100) 68 Andris Pētersons ilgstoša un nežēlīga kara apstākļos, kādi valdīja Baltijā 12. -

Information for the Repatriates Who Are Third Country Nationals

INFORMATION FOR THE REPATRIATES WHO ARE THIRD COUNTRY NATIONALS This material was prepared during a project Evaluation of the necessities of repatriates who are third-country nationals. The project is coofunded by the European Fund for the Integration of Third Country Nationals. The Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs is fully responsible for the content in this material and the views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the the European Union. CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Needs assessment of repatriated third country nationals............................................................ 6 Examples of repatriates experiences while moving to Latvia..................................................... 7 Latvia ............................................................................................................................................................... 9 • Short history of Latvia ............................................................................................ 9 • Stages of emigration ............................................................................................ 10 • Repatriation – return back to Latvia ................................................................ 11 • National holidays .................................................................................................. 11 • Remembrance and festive