The Water Framework Directive in the Baltic Sea Region Countries - Vertical Implementation, Horizontal Integration and Transnational Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar ) in Subdivisions 22–31 (Baltic

ICES Advice on fishing opportunities, catch, and effort Baltic Sea ecoregion Published 29 May 2020 Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in subdivisions 22–31 (Baltic Sea, excluding the Gulf of Finland) ICES advice on fishing opportunities ICES advises that when the precautionary approach is applied, total commercial sea catch in 2021 should be no more than 116 000 salmon, assuming no change in recreational effort. Applying the same catch proportions estimated from observations in the 2019 fishery, the catch in 2021 would be split as follows: 106 000 salmon projected landings (91%; i.e. 83% reported, 7% unreported, and 1% misreported) and projected discards of 10 000 salmon (9%; previously referred to as discards). This would correspond to commercial landings (the reported projected landings) of 96 600 salmon. ICES advises that management of salmon fisheries should be based on the status of individual river stocks. Fisheries on mixed stocks that encompass weak wild stocks present particular threats, and should be kept as close to zero as possible. Fisheries in open-sea areas or in coastal waters target mixed stocks; they are thus more likely to pose a threat to depleted stocks than fisheries in estuaries and in healthy (at or above MSY) wild or reared salmon rivers. The salmon stocks of rivers Rickleån, Sävarån, Öreälven, and Lögdeälven in the Gulf of Bothnia, Emån in southern Sweden, and all rivers in the southeastern Main Basin (AU 5) are particularly weak, and several have shown limited recovery to previous reductions in exploitation rates at sea. The offshore and coastal fisheries in the Main Basin includes catches from all of these weak salmon stocks on their feeding migration. -

East Baltic Vikings - with Particular Consideration to the Ctrronians

East Baltic Vikings - with particular consideration to the Ctrronians Swedish Allies in the Saga World EAST BALTIC At the mythical battlefield of Bravellir (Sw. VIKINGS - WITH Bnl.vallama), Danes and the Swedes clashed in a PARTICULAR fight of epic dimensions. The over-aged Danish king Harald Hildetand finally lost his life, and CONSIDERA his nephew king Sigurdr hringr won Denmark TION TO THE for the Swedes. The story appears in a fragment CURONIANS of a Norse saga from around 1300. But since Sa xo Grammaticus tells it, the written tradition Nils Blornkvist must go back at least to the late 12th century. Wri ting in Latin he prefers to call it bellum Suetici, 'the Swedish war'. It's for several reasons ob vious that Saxo has built his text on a Norse text that must have been quite similar to the preser ved fragment. The battle of Bravellir- the Norse fragment claims - was noteworthy in ancient tales for having be en the greatest, the hardest and the most even and uncertain of the wars that had been fought in the Nordic countries.1 Both sources give long lists of the famous heroes that joined the two armies in a way that recalls the list of ships in Homer's Iliad. These champions are the knight errants of Germanic epics, to some degree rela ted with those of chansons de geste. They are pre sented with characteristic epithets and eponyms that point out their origins in a town, a tribe or a country. When summed up they communicate a geographic vision of the northern World in the 11 th and 12th centuries. -

Latvia Toponymic Factfile

TOPONYMIC FACT FILE Latvia Country name Latvia State title Republic of Latvia Name of citizen Latvian Official language Latvian (lv) Country name in official language Latvija State title in official language Latvijas Republika Script Roman n/a. Latvian uses the Roman alphabet with three Romanization System diacritics (see page 3). ISO-3166 country code (alpha-2/alpha-3) LV / LVA Capital (English conventional) Riga1 Capital in official language Rīga Population 1.88 million2 Introduction Latvia is the central of the three Baltic States3 in north-eastern Europe on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. It has existed as an independent state c.1918 to 1940 and again since 1990. In size it is similar to Sri Lanka or Sierra Leone. Latvia is approximately 1% smaller than neighbouring Lithuania, but has only two-thirds the population, estimated at 1.88 million in 20202. The population has been falling steadily since a high of 2,660,000 in 1989 source: Eurostat). Geographical names policy Latvian is written in Roman script. PCGN recommends using place names as found on official Latvian-language sources, retaining all diacritical marks. Latvian generic terms frequently appear with lower-case initial letters, and PCGN recommends reflecting this style. Allocation and recording of geographical names in Latvia are the responsibility of the Latvia Geospatial Information Agency (Latvian: Latvijas Ģeotelpiskās informācijas aģentūra – LGIA) which is part of the Ministry of Defence (Aizsardzības ministrija). The geographical names database on the LGIA website: http://map.lgia.gov.lv/index.php?lang=2&cPath=3&txt_id=24 is a useful official source for names. -

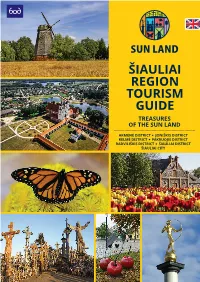

Saules Zemes Turtai EN(6).Pdf

3 SEVEN WONDERS OF THE LAND OF ŠIAULIAI THE HILL OF CROSSES with over 200,000 crosses. Every year, the hill is visited by thousands of tourists from all over the world. SUNDIAL SQUARE with the highest sundial in Lithuania and a gilded sculpture “Šaulys” (“Archer”) that has become the city’s symbol. THE ENSEMBLE OF TYTUVĖNAI CHURCH AND MONASTERY – one of the most interesting and largest examples of Lithuanian sacral architecture, adorned with frescoes, dating back to the 17th-18th centuries. THE BUTTERFLY EXPOSITION – you will find the largest collection of diurnal butterflies in Lithuania in the Akmenė Regional Museum. CHERRIES OF ŽAGARĖ – a four-day cherry festival and the election of the most beautiful scarecrow in one of the most unique Lithuanian towns in Joniškis land. WINDMILLS OF PAKRUOJIS – the wind accelerating in wide plains is turning the vanes of as many as 18 windmills. THE TULIP FLOWERING FESTIVAL – held every spring in the Burbiškis manor, Radviliškis land; as many as half a thousand tulip species burst into flower. 4 4 ŠIAULIAI The centre of the city, which was twice destroyed during the wars of the 20th century and rebuilt again, has distinct architectural heritage of the interwar pe- riod modernism, which has survived to this day. Šiauliai is a city-phoenix, every time rising from ashes. Discover Šiauliai and experience the magic of 3 “S”: sweets, special museums, and the sun. The symbols of the sun, scattered all over the city (sundials, stained glass, etc.), have become an integral part of the city. The oldest sweet factory of Lithuania, “Rūta”, operating for over 100 years, special museums of chocolate, photogra- phy, telephony, and the only such Vanda Kavaliauskienė’s Cats Museum with over 4000 exhibits. -

Ancient Natural Sacred Sites in Kurzeme Region, Latvia

dating back to 1234 about enfeoffing of 25 acres of land 5 to the Riga St. Peter’s Church, was situated. The hill fort IN THE WAKE OF THE CURONIANS was located in the Curonian land of Vanema. The Mežīte Hill Fort was constructed on a solitary, about 13 m high Longer distances of the route are hill, the slopes of which had been artificially made steep- heading along asphalt roads, but 3 The CURONIAN HILL FORT er. Its plateau is of a triangular form, 55 x 30–50 m large, access to ancient cult sites mostly is OF VeCKULDīGA with a narrower southern part, on which a 3 meters high available along gravel and forest roads. Kuldīga 56º59’664 21º57’688 rampart had been heaped up. It used to protect the as- Long before the introduction of Christianity in cent to the hill fort, which, just like in many other Latvian Length of the route 145 km the ancient land of Cursa and expansion of the hill forts, was planned in such a way that when invaders 9 10 22 Livonian Order, on the present site of the hill fort of were striving to conquer the hill fort, their shoulders, Veckuldīga, at the significant waterway of the Venta unprotected by a shield, would be turned against the 21 has been observed: in the nearby trees, there have ancestors’ traditions are still kept alive by celebrating cult tree, its age could be around 400–500 years. River, one of the largest and best fortified castles of hill fort’s defenders. -

Application Form for Listing Under the “European Heritage Label” Scheme

Application form for listing under the “European Heritage Label” scheme Country Latvia Region/province Kurzeme region, Kuldiga city Name of the cultural property1, monument, natural or urban site2, Kuldiga or site that has played a key role in European history. Owner the cultural property, Kuldiga Municipality monument, natural or urban site, or site that has played a key role in European history Public or private authorities Kuldiga Town Council responsible for the site or property (delegated management) Postal address Geographic coordinates Geographical location: Latitude 56°58’03’’; Longitude 21°58’14’’ The property is located in the western part of Latvia, in Kuldiga district, 150 km from Riga, the capital of Latvia. See attached map – appendix nr. 1. Reasons for listing Kuldiga is a little unique old town, which is significant for Preserved town planning of middle age style; Preserved splendid wooden buildings of 17-19 centuries; There is the widest waterfall in all the Europe situated (the width is 249 - 275 m depending from season); The coasts of the riversides are linked with old, one of the longest brick bridges; Since 1368 Kuldiga has been a member of the Hanseatic League; It is the native town of the duke Jacob; In 1595-1618, has been a capital of Kurland. Kuldiga is a province town of the Baltic region where number of unique values is concentrated at one place. There is specific town environment with unrepeatable social life where dominates throw centuries unchanged romantic and intimate spirit. Kuldiga old town fulfils following criteria – site of cultural and historical interest that have particular European significance for Member States in general and urban and natural area, riverside archaeological site. -

Recreational Fishing in the Baltic Sea Region

PROTECTING THE BALTIC SEA ENVIRONMENT - WWW.CCB.SE RECREATIONAL FISHING IN THE BALTIC SEA REGION Coalition Clean Baltic Researched and written by Niki Sporrong for Coalition Clean Baltic E-mail: [email protected] Address: Östra Ågatan 53, 753 22 Uppsala, Sweden www.ccb.se © Coalition Clean Baltic 2017 With the contribution of the LIFE financial instrument of the European Community and the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management Contents Background ...................................................................................................................4 Introduction ..................................................................................................................5 Summary .......................................................................................................................6 Terminology .................................................................................................................12 Finland (not including Åland1) .....................................................................................15 Estonia ..........................................................................................................................23 Latvia ............................................................................................................................32 Lithuania ......................................................................................................................39 Russia (Kaliningrad region) ..........................................................................................45 -

DRAINAGE BASIN of the BALTIC SEA Chapter 8

216 DRAINAGE BASIN OF THE BALTIC SEA Chapter 8 BALTIC SEA 217 219 TORNE RIVER BASIN 221 KEMIJOKI RIVER BASIN 222 OULUJOKI RIVER BASIN 223 JÄNISJOKI RIVER BASIN 224 KITEENJOKI-TOHMAJOKI RIVER BASINS 224 HIITOLANJOKI RIVER BASIN 226 VUOKSI RIVER BASIN 228 LAKE PYHÄJÄRVI 230 LAKE SAIMAA 232 JUUSTILANJOKI RIVER BASIN 232 LAKE NUIJAMAANJÄRVI 233 RAKKOLANJOKI RIVER BASIN 235 URPALANJOKI RIVER BASIN 235 NARVA RIVER BASIN 237 NARVA RESERVOIR 237 LAKE PEIPSI 238 GAUJA/KOIVA RIVER BASIN 239 DAUGAVA RIVER BASIN 241 LAKE DRISVYATY/ DRUKSHIAI 242 LIELUPE RIVER BASIN 245 VENTA, BARTA/BARTUVA AND SVENTOJI RIVER BASINS 248 NEMAN RIVER BASIN 251 LAKE GALADUS 251 PREGEL RIVER BASIN 254 VISTULA RIVER BASIN 260 ODER RIVER BASIN Chapter 8 218 BALTIC SEA This chapter deals with major transboundary rivers discharging into the Baltic Sea and some of their transboundary tributaries. It also includes lakes located within the basin of the Baltic Sea. TRANSBOUNDARY WATERS IN THE BASIN OF THE BALTIC SEA1 Basin/sub-basin(s) Total area (km²) Recipient Riparian countries Lakes in the basin Torne 40,157 Baltic Sea FI, NO, SE Kemijoki 51,127 Baltic Sea FI, NO, RU Oulujoki 22,841 Baltic Sea FI, RU Jänisjoki 3,861 Lake Ladoga FI, RU Kiteenjoki-Tohmajoki 1,595 Lake Ladoga FI, RU Hiitolanjoki 1,415 Lake Ladoga FI, RU Lake Pyhäjärvi and Vuoksi 68,501 Lake Ladoga FI, RU Lake Saimaa Juustilanjoki 296 Baltic Sea FI, RU Lake Nuijamaanjärvi Rakkonlanjoki 215 Baltic Sea FI, RU Urpanlanjoki 557 Baltic Sea FI, RU Saimaa Canal including 174 Baltic Sea FI, RU Soskuanjoki Tervajoki 204 -

CHANGES of TOTAL ANNUAL RUNOFF DISTRIBUTION, HIGH and LOW DISCHARGES in LATVIAN RIVERS Elga Apsîte*, Anda Bakute*, and Ilze Rudlapa**

PROCEEDINGS OF THE LATVIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES. Section B, Vol. 63 (2009), No. 6 (665), pp. 279–286. DOI: 10.2478/v10046-010-0004-y CHANGES OF TOTAL ANNUAL RUNOFF DISTRIBUTION, HIGH AND LOW DISCHARGES IN LATVIAN RIVERS Elga Apsîte*, Anda Bakute*, and Ilze Rudlapa** * Faculty of Geography and Earth Sciences, University of Latvia, Raiòa bulv. 19, Rîga, LV-1586, LATVIA, E-mail: [email protected] ** Latvian Environment, Geology and Meteorology Agency, Maskavas iela 165, Rîga, LV-1019, LATVIA Communicated by Mâris Kïaviòð The paper examines climate change impacts on the hydrological regime of nineteen different river basins in Latvia. Hydrological data series for the period of 1951–2006 were analysed for river ba- sins of four hydrological districts: Western, Central, Northern and Eastern. Climate change has in- fluenced the temporal and spatial distribution of total annual river runoff and high and low flows in Latvia at the turn of century. The results confirm the hypothesis that the main tendency in the run- off change is a decrease in spring floods and increase in winter. Generally, statistically insignifi- cant long-term trends were observed for summer and autumn. Key words: river runoff, high and low flows, trends, climate change, Latvia. INTRODUCTION Ziverts and Apsite (2005), Rogozova (2006). These studies showed seasonal changes of long-term river runoff and ice Climate change impacts on rivers hydrological regime have regime. For example, Frisk et al. (2002) concluded that in been extensively studied world-wide (Hisdal et al., 2003; general the discharge changes are minimal and have in- Pekarova et al., 2006; Rödel, 2006; Rees and Collins, 2006; creased only in the main rivers in Latvia. -

Online Conflict Discourse, Identity, and the Social Imagination of Silesian Minority in Poland by Krzysztof E

Online Conflict Discourse, Identity, and the Social Imagination of Silesian Minority in Poland By Krzysztof E. Borowski © 2020 Krzysztof E. Borowski M.A., University of Wrocław, 2011 B.A., University of Wrocław, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Slavic Languages and Literatures and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Marc L. Greenberg Co-Chair: Renee Perelmutter Svetlana Vassileva-Karagyozova Arienne Dwyer Nathan Wood Date Defended: 29 April 2020 ii The dissertation committee for Krzysztof E. Borowski certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Online Conflict Discourse, Identity, and the Social Imagination of Silesian Minority in Poland Co-Chair: Marc L. Greenberg Co-Chair: Renee Perelmutter Date Approved: 29 April 2020 iii Abstract The second decade of the twenty-first century has been that of digital nationalism. In particular, the 2016 United States presidential elections and Brexit vote in the United Kingdom have shown that the increased use of social media has raised popular nationalism (Whitmeyer 2002) to a whole new level. While Europe and other parts of the world have visibly become more globalized, the Northern Atlantic region has witnessed a contradictory tendency for the rise and spread of nationalist sentiment. Much of this phenomenon has been taking place on the internet where conditions of apparent anonymity created a fertile ground for uninhibited identity expressions and performances. From the United States to Poland, people have retreated to their stable, national identities as a way of coping with the various facets of liquid modernity, in which the need for networking pushes individuals to engage in community building by bonding with other individuals through shared emotions (Bauman 2006, 37). -

International River Basins in the Baltic Sea Region

Project part-financed by the European Union (European Regional Development Fund) within the BSR INTERREG III B Programme International river basins in the Baltic Sea Region February 2006 By Susanna Nilsson, Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Department of Land and Water Resources Engineering ([email protected]) There are 14 larger international river basins within the Baltic Sea Drainage Basin. These river basins vary in size, number of countries sharing the basins, environmental problems experienced and the way they are managed. But, they do have something in common. They are all international and they are all situated in the same geographical area, the Baltic Sea Region. The Interreg IIIB project TRABANT, launched to address topical issues in international water management, has decided to set up a small “fact sheet” for international river basins within the Baltic Sea Region. The fact sheet gives an overview of international cooperation and pressures on and status of water resources in the international basins. This may be of interest to water managers, stakeholders and other interested in international water Figure 1. Fourteen largest international river management in the region. basins in the Baltic Sea Drainage Basin. Description Daugava, Lielupe, Venta, Nemunas, The Baltic Sea Drainage Basin (BSDB) is Vistula, Pregola and Oder. a large heterogeneous region. The drainage basin covers an area of 1 739 For each river basin, a one-page “fact 2 000 km , is shared by 14 countries sheet” has been produced. Each fact (Belarus, Czech Republic, Denmark, sheet lists the following information: Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Russia, • Area of basin (km2) Slovakia, Sweden and Ukraine) and home • Population (total number of to about 84 million people (Hannerz and inhabitants) Destouni, 2005). -

Poland As the Destination for Business Services Centres

KPMG in Poland Poland as the destination for Business Services Centres 2015 Edition kpmg.pl 2 | Section or Brochure name © 2015 KPMG Sp. z o.o., a Polish limited liability company and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. Poland as the destination for Business Services Centres | 3 Foreword Poland is one of the most attractive destinations for business service centres worldwide. Tholons in its report 2015 TOP 100 Outsourcing Destinations ranks Kraków as the 9th top service location worldwide. A recent report published by the Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency and Hays shows that in Poland there are over 650 business service centres employing over 150,000 people. KPMG’s IT Outsourcing Service Provider Performance & Satisfaction Study published in March 2015 shows that Poland is the #2 location for IT outsourcing services according to the surveyed organisations, 450 polled in this survey worldwide. The importance of the service industry for the Polish economy has been also recognised by the Polish government and local authorities in cities that are attracting more and more investors. KPMG has dedicated global Shared Services and Outsourcing Advisory (SSOA) teams that service various companies, taking care of the entire lifecycle of business services centres, or outsourcing contracts, from design to implementation, and performance improvement. Many of our clients are making the decision on where to locate their global business centre, extend the existing business center, or they are redefining their global sourcing strategy. Our Polish team that is a part of the global SSOA practice supports many businesss services centers in Poland.