Tectonic-Sedimentary System of the Atlantis‒Meteor Seamounts (North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mantle Dynamics and Characteristics of the Azores Plateau

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 362 (2013) 258–271 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Mantle dynamics and characteristics of the Azores plateau C. Adam a,n, P. Madureira a,b, J.M. Miranda c, N. Lourenc-o c,d, M. Yoshida e, D. Fitzenz a,1 a Centro de Geofı´sica de E´vora/Univ. E´vora, 7002-554 E´vora, Portugal b Estrutura de Missao~ para a Extensao~ da Plataforma Continental (EMEPC), 2770-047, Pac-o d’ Arcos, Portugal c Instituto Portugues do Mar e da Atmosfera, Lisboa, Portugal d University of Algarve, IDL, Campus de Gambelas, 8000 Faro, Portugal e Institute for Research on Earth Evolution (IFREE), Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), Yokosuka, Kanagawa 237-0061, Japan article info abstract Article history: Situated in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, the Azores plateau is a region of elevated topography Received 25 July 2012 encompassing the triple junction between the Eurasian, Nubian and North American plates. The plateau is Received in revised form crossed by the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and the Terceira Rift is generally thought of as its northern boundary. 2 November 2012 The origin of the plateau and of the Terceira Rift is still under debate. This region is associated with active Accepted 5 November 2012 volcanism. Geophysical data describe complex tectonic and seismic patterns. The mantle under this region Editor: T. Spohn Available online 18 January 2013 is characterized by anomalously slow seismic velocities. However, this mantle structure has not yet been used to quantitatively assess the influence of the mantle dynamics on the surface tectonics. -

S41598-020-76691-1 1 Vol.:(0123456789)

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Rifting of the oceanic Azores Plateau with episodic volcanic activity B. Storch1*, K. M. Haase1, R. H. W. Romer1, C. Beier1,2 & A. A. P. Koppers3 Extension of the Azores Plateau along the Terceira Rift exposes a lava sequence on the steep northern fank of the Hirondelle Basin. Unlike typical tholeiitic basalts of oceanic plateaus, the 1.2 km vertical submarine stratigraphic profle reveals two successive compositionally distinct basanitic to alkali basaltic eruptive units. The lower unit is volumetrically more extensive with ~ 1060 m of the crustal profle forming between ~ 2.02 and ~ 1.66 Ma, followed by a second unit erupting the uppermost ~ 30 m of lavas in ~ 100 kyrs. The age of ~ 1.56 Ma of the youngest in-situ sample at the top of the profle implies that the 35 km-wide Hirondelle Basin opened after this time along normal faults. This rifting phase was followed by alkaline volcanism at D. João de Castro seamount in the basin center indicating episodic volcanic activity along the Terceira Rift. The mantle source compositions of the two lava units change towards less radiogenic Nd, Hf, and Pb isotope ratios. A change to less SiO2-undersaturated magmas may indicate increasing degrees of partial melting beneath D. João de Castro seamount, possibly caused by lithospheric thinning within the past 1.5 million years. Our results suggest that rifting of oceanic lithosphere alternates between magmatically and tectonically dominated phases. Oceanic plateaus with a crustal thickness to 30 km cover large areas in the oceans and these bathymetric swells afect oceanic currents and marine life 1,2. -

PDF Linkchapter

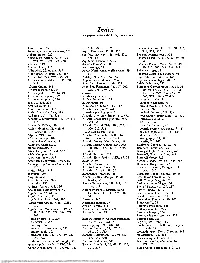

Index [Italic page numbers indicate major references] Abaco Knoll, 359 116, 304, 310, 323 Bahama Platform, 11, 329, 331, 332, Abathomphalus mayaroensis, 101 Aquia Formation, 97, 98, 124 341, 358, 360 Abbott pluton, 220 aquifers, 463, 464, 466, 468, 471, Bahama volcanic crust, 356 Abenaki Formation, 72, 74, 257, 476, 584 Bahamas basin, 3, 5, 35, 37, 39, 40, 259, 261, 369, 372, 458 Aquitaine, France, 213, 374 50 ablation, 149 Arcadia Formation, 505 Bahamas Fracture Zone, 24, 39, 40, Abyssal Plain, 445 Archaean age, 57 50, 110, 202, 349, 358, 368 Adirondack Mountains, 568 Arctic-North Atlantic rift system, 49, Bahamas Slope, 12 Afar region, Djibouti, 220, 357 50 Bahamas-Cuban Fault system, 50 Africa, 146, 229, 269, 295, 299 Ardsley, New York, 568, 577 Baja California, Mexico, 146 African continental crust, 45, 331, Argana basin, Morocco, 206 Bajocian assemblages, 20, 32 347 Argo Fan, Scotian margin, 279 Balair fault zone, 560 African Craton, 368 Argo Salt Formation, 72, 197, 200, Baltimore Canyon trough, 3, 37, 38, African margin, 45, 374 278, 366, 369, 373 40, 50, 67, 72 , 81, 101, 102, African plate, 19, 39, 44, 49 arkoses, 3 138, 139, 222, 254, 269, 360, Afro-European plate, 197 artesian aquifers, 463 366, 369, 396, 419,437 Agamenticus pluton, 220 Ashley Formation, 126 basement rocks, 74 age, 19, 208, 223 Astrerosoma, 96 carbonate deposits, 79 Agulhas Bank, 146 Atkinson Formation, 116, 117 crustal structure, 4, 5, 46 Aiken Formation, 125 Atlantic basin, 6, 9, 264 faults in, 32 Aikin, South Carolina, 515 marine physiography, 9 geologic -

98-031 Oceanus F/W 97 Final

A hotspot created the island of Iceland and its characteristic volcanic landscape. Hitting the Hotspots Hotspots are rela- tively small regions on the earth where New Studies Reveal Critical Interactions unusually hot rocks rise from deep inside Between Hotspots and Mid-Ocean Ridges the mantle layer. Jian Lin Associate Scientist, Geology & Geophysics Department he great volcanic mid-ocean ridge system hotspots may play a critical role in shaping the stretches continuously around the globe for seafloor—acting in some cases as strategically T 60,000 kilometers, nearly all of it hidden positioned supply stations that fuel the lengthy beneath the world’s oceans. In some places, how- mid-ocean ridges with magma. ever, mid-ocean ridge volcanoes are so massive that Studies of ridge-hotspot interactions received a they emerge above sea level to create some of the major boost in 1995 when the US Navy declassified most spectacular islands on our planet. Iceland, the gravity data from its Geosat satellite, which flew Azores, and the Galápagos are examples of these from 1985 to 1990. The satellite recorded in unprec- “hotspot” islands—so named because they are edented detail the height of the ocean surface. With believed to form above small regions scattered accuracy within 5 centimeters, it revealed small around the earth where unusually hot rocks rise bumps and dips created by the gravitational pull of from deep inside the mantle layer. dense underwater mountains and valleys. Research- But hotspots may not be such isolated phenom- ers often use precise gravity measurements to probe ena. Exciting advances in satellite oceanography, unseen materials below the ocean floor. -

Hotspots and Mantle Plumes Pdf

Hotspots and mantle plumes pdf Continue The mantle feathers area is hot, upwelling the mantle. A hot spot develops above the train. Magma, generated by a hot spot, rises through rigid slabs of the lithosphere and produces active volcanoes on the Earth's surface. As ocean volcanoes move away from the hotspot, they cool and subside, producing old islands, atolls and seamounts. As continental volcanoes move away from the hotspot, they cool, subside and die out. Hot spots are places inside the mantle where stones melt to generate magma. The presence of a hot spot stems from abnormal volcanism (i.e. not on the plate boundary) such as Hawaiian volcanoes within the Pacific Plate. The Hawaiian hotspot has been active for at least 70 million years, producing a volcanic chain that stretches for 3,750 miles (6,000 km) across the Pacific Northwest. Hot spots also develop under continents. Yellowstone hot spot has been active for at least 15 million years, producing a chain of caldera and volcanic features along the plains of the Snake River, which stretches 400 miles (650 km) west from northwest Wyoming to the Idaho-Oregon border. Keep in mind, however, that these are just theories. No one knows the answer. The honest answer is that many people are working on it but have not yet come up with an answer. Graphics After Morgan, J., 1971, Convection feathers in the lower mantle: Nature, art 230, p. 42-43. Volcanic regions, which are thought to feed on the underlying mantle, are abnormally hot compared to the surrounding mantle Diagram, showing a cross-section across the Earth's lithosphere (yellow) with magma rising from the mantle (red). -

Northward Drift of the Azores Plume in the Earth’S Mantle

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11127-7 OPEN Northward drift of the Azores plume in the Earth’s mantle Maëlis Arnould 1,2,3, Jérôme Ganne4, Nicolas Coltice1 & Xiaojun Feng 5 Mantle plume fixity has long been a cornerstone assumption to reconstruct past tectonic plate motions. However, precise geochronological and paleomagnetic data along Pacific continuous hotspot tracks have revealed substantial drift of the Hawaiian plume. The 1234567890():,; question remains for evidence of drift for other mantle plumes. Here, we use plume-derived basalts from the Mid-Atlantic ridge to confirm that the upper-mantle thermal anomaly associated with the Azores plume is asymmetric, spreading over ~2,000 km southwards and ~600 km northwards. Using for the first time a 3D-spherical mantle convection where plumes, ridges and plates interact in a fully dynamic way, we suggest that the extent, shape and asymmetry of this anomaly is a consequence of the Azores plume moving northwards by 1–2 cm/yr during the past 85 Ma, independently from other Atlantic plumes. Our findings suggest redefining the Azores hotspot track and open the way for identifying how plumes drift within the mantle. 1 Laboratoire de Géologie, École Normale Supérieure, CNRS UMR 8538, PSL Research University, 75005 Paris, France. 2 Laboratoire de Géologie de Lyon, Terre, Planètes, Environnement, École Normale Supérieure de Lyon, Université de Lyon, Université Claude Bernard, CNRS UMR 5276, 2 rue Raphaël Dubois, 69622 Villeurbanne, France. 3 EarthByte Group, School of Geosciences, Madsen Building F09, University of Sydney, Sydney 2006 NSW, Australia. 4 IRD, CNRS, GET, Université Toulouse III, 14 Avenue Edouard Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France. -

Source Characteristics of Jurassic Ferropicrites from Dronning Maud

A106 Goldschmidt Conference Abstracts 2005 Basalt Geochemistry and Mantle Dynamics Source characteristics of Jurassic The Azores hotspot: A lower mantle ferropicrites from Dronning Maud origin for Terceira magmas as shown Land, Antarctica by Ne isotopic data 1 2 1,2 1 3 A.V. LUTTINEN AND H. HUHMA P. MADUREIRA , M. MOREIRA AND J. MATA 1Department of Geology, P.O.Box 64, FI-00014 University of 1Institut de Physique du globe de Paris, Université paris VII, Helsinki, Finland ([email protected]) CNRS UMR 7579, 4 place Jussieu, 75005 Paris, France 2Geological Survey of Finland, P.O.Box 123, FI-21520 Espoo, ([email protected]) Finland ([email protected]) 2Centro de Geofísica de Évora/Departamento de Geociências da Universidade de Évora, Rua Romão Ramalho, 59, Middle Jurassic basalts of Vestfjella, western Dronning 7000-671 Évora, Portugal ([email protected]) Maud Land comprise an Antarctic extension of the Karoo 3Centro e Departamento de Geologia da Faculdade de large igneous province. In addition to intrusive equivalents of Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande, the lavas, crosscutting dolerite dikes include a group of C6-4º Piso, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal ([email protected]) picrites with unusually high total FeO (>14 wt.%) and low Al2O3 (<10 wt.%) at given MgO (10–18 wt.%). The picrites The collection of helium isotopic data in the last twenty are probably coeval, or nearly so, with the lavas, although years has shown different signatures for MORB and OIB precise age data are lacking. Mantle-normalised incompatible basalts and this has been used as the basis for the two-layer element fingerprints indicate two subgroups of such mantle model. -

Upper Mantle Structure Beneath the Azores Hotspot from Finite-Frequency Seismic Tomography ⁎ Ting Yang A, , Yang Shen A, Suzan Van Der Lee B, Sean C

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 250 (2006) 11–26 www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Upper mantle structure beneath the Azores hotspot from finite-frequency seismic tomography ⁎ Ting Yang a, , Yang Shen a, Suzan van der Lee b, Sean C. Solomon c, Shu-Huei Hung d a Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, Narragansett, RI 02882, USA b Department of Geological Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA c Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, DC 20015, USA d Department of Geosciences, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan Received 6 February 2006; received in revised form 13 July 2006; accepted 14 July 2006 Available online 28 August 2006 Editor: S. King Abstract The Azores archipelago is a classic expression of a hotspot that has interacted with a mid-ocean ridge. A variety of geochemical studies and geophysical observations point to the influence of some sort of mantle plume on the formation of the Azores Plateau and the adjacent Mid-Atlantic Ridge (MAR), but the mantle structure beneath the Azores has not heretofore been imaged tomographically at a sufficiently fine resolution to resolve a narrow plume. We present a P-wave velocity model of the mantle beneath the hotspot derived from teleseismic body waves recorded by six broadband seismic stations on the Azores Islands including the Global Seismographic Network station CMLA. Three-dimensional travel-time sensitivity kernels are used to account for the effects of wavefront healing and scattering of seismic waves. An inversion of 228 P-wave travel-time delays reveal a low- velocity anomaly in the shallow mantle (less than 200 km deep) along the Azores archipelago and beneath the Azores Plateau (centered approximately at 38.5°N, 28.5°W). -

Sleep, N.H., Hotspots and Mantle Plumes: Some Phenomenology, J

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 95, NO. B5, PAGES 6715-6736, MAY 10, 1990 Hotspotsand Mantle Plumes'Some Phenomenology NORMAN H. SLEEP Departmentsof Geologyand Geophysics,Stanford University, Stanford, California The availabledata, mainly topography, geoid, and heat flow, describinghotspots worldwide are examined to constrainthe mechanismsfor swelluplift and to obtainfluxes and excess temperatures of mantleplumes. Swelluplift is causedmainly by excesstemperatures that move with the lithosphereplate and to a lesser extenthot asthenospherenear the hotspot.The volume,heat, and buoyancy fluxes of hotspotsare computed fromthe cross-sectionalareas of swells,the shapes of nosesof swells,and, for on ridgehotspots, the amount of ascendingmaterial needed to supplythe lengthof ridgeaxis whichhas abnormallyhigh elevationand thickcrust. The buoyancy fluxes range over a factorof 20 withHawaii, 8.7 Mg s -1, thelargest. The buoy- ancyflux for Iceland is 1.4Mg s -1 whichis similarto theflux of CapeVerde. The excess temperature of both on-ridgeand off-ridgehotspots is aroundthe 200øCvalue inferred from petrologybut is not tightly constrainedby geophysicalconsiderations. This observation,the similarityof the fluxesof on-ridgeand off- ridgeplumes, and the tendency for hotspotsto crossthe ridge indicate that similar plumes are likely to cause both typesof hotspots.The buoyancyfluxes of 37 hotspotsare estimated;the globalbuoyancy flux is 50 Mgs -1, whichis equivalentto a globallyaveraged surface heat flow of 4 mWm-2 fromcore sources and wouldcool the core at a rateof 50ø C b.y. -1. Basedon a thermalmodel and the assumption that the likeli- hoodof subductionis independentof age,most of the heatfrom hotspotsis implacedin the lower litho- sphereand later subducted. I.NTRODUCWION ridge plumesusing Iceland as an example. The geometryof flow implied by the assumed existence of a low viscosity Linearseamount chains, such as the Hawaiian Islands, are asthenosphericchannelis illustrated bythis exercise. -

Geoscenario Resources—Yellowstone Hotspot

Geoscenario Resources—Yellowstone Hotspot: Geologist Task Now that you have explored as a team, the general story of the Yellowstone Hotspot, it is time for each of you to dive into more specialized information. The geologist focuses on the historic path of the Yellowstone Hotspot and how the major geothermal features work. Add helpful details to your notes for Geoscenario Team Questions. Then work together and combine all the information to successfully present your story of the Yellowstone Hotspot. Questions for the Geologist to Consider • How do the major geothermal features in Yellowstone work? • What is the historic path of the Yellowstone Hotspot? Information Water cools near the vent’s surface. Yellowstone National Park is known for its This cooler water “caps” the hotter diverse hydrothermal features. How do they water below. Eventually, superheated work? These diagrams explain how geysers build Side channels can often release pressure water flashes to steam, expanding and within thermal systems. Side channels lifting the water above the vent in an pressure to erupt and why hot springs are so blue. can act as indicators of when primary- eruption. The brilliant colors in hot springs come from feature eruptions may occur. archaebacteria. Aptly called extremophiles for Silica is dissolved from rhyolite (the their ability to survive in extreme environments, Side Channel volcanic rock) and precipitates as these colorful organisms can live in extremely sinter, which forms the geyser cone. high temperatures. Scientists study these bacteria Sinter Sinter to understand how their cells and proteins can Sinter is deposited on the walls and acts High-pressure area caused by survive and function in environmental conditions like a throttle in the vent by constricting expanding water and steam. -

Northward Drift of the Azores Plume in the Earth's Mantle

Northward drift of the Azores plume in the Earth’s mantle Maëlis Arnould, Jérôme Ganne, Nicolas Coltice, Xiaojun Feng To cite this version: Maëlis Arnould, Jérôme Ganne, Nicolas Coltice, Xiaojun Feng. Northward drift of the Azores plume in the Earth’s mantle. Nature Communications, Nature Publishing Group, 2019, 10, pp.3235. 10.1038/s41467-019-11127-7. hal-03228578 HAL Id: hal-03228578 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03228578 Submitted on 18 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Northward drift of the Azores plume in the Earth’s mantle 2 Maëlis Arnould1,2, Jérôme Ganne3, Nicolas Coltice4, Xiaojun Feng5 3 4 5 1 - LGL TPE, UMR CNRS 5276 (CNRS, ENS, Université Lyon1), Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon 69364 6 Lyon cedex 07, France 7 2 – EarthByte Group, School of Geosciences, Madsen Building F09, University of Sydney, NSW, 2006, 8 Australia 9 3 - IRD, CNRS, GET, Université Toulouse III, 14 Avenue Edouard Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France 10 4 - Laboratoire de Géologie, École Normale Supérieure, CNRS UMR 8538, PSL Research University, Paris 11 75005, France 12 5 - School of Safety Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology, Jiangsu, China 13 14 15 16 17 18 ABSTRACT 19 20 The fixity of mantle plumes has been a cornerstone assumption for the reconstruction of tectonic plate motions1. -

7.09 Hot Spots and Melting Anomalies G

7.09 Hot Spots and Melting Anomalies G. Ito, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA P. E. van Keken, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA ª 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 7.09.1 Introduction 372 7.09.2 Characteristics 373 7.09.2.1 Volcano Chains and Age Progression 373 7.09.2.1.1 Long-lived age-progressive volcanism 373 7.09.2.1.2 Short-lived age-progressive volcanism 381 7.09.2.1.3 No age-progressive volcanism 382 7.09.2.1.4 Continental hot spots 383 7.09.2.1.5 The hot-spot reference frame 386 7.09.2.2 Topographic Swells 387 7.09.2.3 Flood Basalt Volcanism 388 7.09.2.3.1 Continental LIPs 388 7.09.2.3.2 LIPs near or on continental margins 389 7.09.2.3.3 Oceanic LIPs 391 7.09.2.3.4 Connections to hot spots 392 7.09.2.4 Geochemical Heterogeneity and Distinctions from MORB 393 7.09.2.5 Mantle Seismic Anomalies 393 7.09.2.5.1 Global seismic studies 393 7.09.2.5.2 Local seismic studies of major hot spots 395 7.09.2.6 Summary of Observations 399 7.09.3 Dynamical Mechanisms 400 7.09.3.1 Methods 400 7.09.3.2 Generating the Melt 401 7.09.3.2.1 Temperature 402 7.09.3.2.2 Composition 402 7.09.3.2.3 Mantle flow 404 7.09.3.3 Swells 405 7.09.3.3.1 Generating swells: Lubrication theory 405 7.09.3.3.2 Generating swells: Thermal upwellings and intraplate hot spots 407 7.09.3.3.3 Generating swells: Thermal upwellings and hot-spot–ridge interaction 408 7.09.3.4 Dynamics of Buoyant Upwellings 410 7.09.3.4.1 TBL instabilities 410 7.09.3.4.2 Thermochemical instabilities 411 7.09.3.4.3 Effects of variable mantle properties 412 7.09.3.4.4 Plume