Geoscenario Resources—Yellowstone Hotspot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hot Spots and Plate Movement Exercise

Name(s) Hot Spots and Plate Movement exercise Two good examples of present-day hot spot volcanism, as derived from mantle plumes beneath crustal plates, are Kilauea, Hawaii (on the Pacific oceanic plate) and Yellowstone (on the continental North American plate). These hot spots have produced a chain of inactive volcanic islands or seamounts on the Pacific plate (Fig. 1) and volcanic calderas or fields on the North American plate (Fig. 2) – see the figures below. Figure 1. Chain of islands and seamounts produced by the Hawaiian hot spot. Figure 2. Chain of volcanic fields produced by the Yellowstone hot spot. The purposes of this exercise are to use locations, ages, and displacements for each of these hot spot chains to determine 1. Absolute movement directions, and 2. Movement rates for both the Pacific and western North American plates, and then to use this information to determine 3. Whether the rates and directions of the movement of these two plates have been the same or different over the past 16 million years. This exercise uses the Pangaea Breakup animation, which is a KML file that runs in the standalone Google Earth application. To download the Pangaea Breakup KML file, go here: http://csmgeo.csm.jmu.edu/Geollab/Whitmeyer/geode/pangaeaBreakup /PangaeaBreakup.kml To download Google Earth for your computer, go here: https://www.google.com/earth/download/ge/agree.html Part 1. Hawaiian Island Chain Load the PangaeaBreakup.kml file in Google Earth. Make sure the time period in the upper right of the screen says “0 Ma” and then select “Hot Spot Volcanos” under “Features” in the Places menu on the left of the screen. -

Kinematic Reconstruction of the Caribbean Region Since the Early Jurassic

Earth-Science Reviews 138 (2014) 102–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Kinematic reconstruction of the Caribbean region since the Early Jurassic Lydian M. Boschman a,⁎, Douwe J.J. van Hinsbergen a, Trond H. Torsvik b,c,d, Wim Spakman a,b, James L. Pindell e,f a Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands b Center for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED), University of Oslo, Sem Sælands vei 24, NO-0316 Oslo, Norway c Center for Geodynamics, Geological Survey of Norway (NGU), Leiv Eirikssons vei 39, 7491 Trondheim, Norway d School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, WITS 2050 Johannesburg, South Africa e Tectonic Analysis Ltd., Chestnut House, Duncton, West Sussex, GU28 OLH, England, UK f School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3YE, UK article info abstract Article history: The Caribbean oceanic crust was formed west of the North and South American continents, probably from Late Received 4 December 2013 Jurassic through Early Cretaceous time. Its subsequent evolution has resulted from a complex tectonic history Accepted 9 August 2014 governed by the interplay of the North American, South American and (Paleo-)Pacific plates. During its entire Available online 23 August 2014 tectonic evolution, the Caribbean plate was largely surrounded by subduction and transform boundaries, and the oceanic crust has been overlain by the Caribbean Large Igneous Province (CLIP) since ~90 Ma. The consequent Keywords: absence of passive margins and measurable marine magnetic anomalies hampers a quantitative integration into GPlates Apparent Polar Wander Path the global circuit of plate motions. -

Shape of the Subducted Rivera and Cocos Plates in Southern Mexico

JOURNALOF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 100, NO. B7, PAGES 12,357-12,373, JULY 10, 1995 Shapeof the subductedRivera and Cocosplates in southern Mexico: Seismic and tectonicimplications Mario Pardo and Germdo Sufirez Insfitutode Geoffsica,Universidad Nacional Aut6noma de M6xico Abstract.The geometry of thesubducted Rivera and Cocos plates beneath the North American platein southernMexico was determined based on the accurately located hypocenters oflocal and te!eseismicearthquakes. The hypocenters ofthe teleseisms were relocated, and the focal depths of 21 eventswere constrainedusing a bodywave inversion scheme. The suductionin southern Mexicomay be approximated asa subhorizontalslabbounded atthe edges by the steep subduction geometryof theCocos plate beneath the Caribbean plate to the east and of theRivera plate beneath NorthAmerica to thewest. The dip of theinterplate contact geometry is constantto a depthof 30 kin,and lateral changes in thedip of thesubducted plate are only observed once it isdecoupled fromthe overriding plate. On thebasis of theseismicity, the focal mechanisms, and the geometry ofthe downgoing slab, southern Mexico may be segmented into four regions ß(1) theJalisco regionto thewest, where the Rivera plate subducts at a steepangle that resembles the geometry of theCocos plate beneath the Caribbean plate in CentralAmerica; (2) theMichoacan region, where thedip angleof theCocos plate decreases gradually toward the southeast, (3) theGuerrero-Oaxac.a region,bounded approximately by theonshore projection of theOrozco and O'Gorman -

Plate Tectonics Review from Valerie Nulisch Some Questions (C) 2017 by TEKS Resource System

Plate Tectonics Review from Valerie Nulisch Some questions (c) 2017 by TEKS Resource System. Some questions (c) 2017 by Region 10 Educational Service Center. Some questions (c) 2017 by Progress Testing. Page 2 GO ON A student wanted to make a model of the Earth. The student decided to cut a giant Styrofoam ball in half and paint the layers on it to show their thickness. 1 Which model below best represents the layers of the Earth? A B C D Page 3 GO ON 2 A student is building a model of the layers of the Earth. Which material would best represent the crust? F Grouping of magnetic balls G Styrofoam packing pellets H Bag of shredded paper J Thin layer of graham crackers 3 Your teacher has asked you to make a model of the interior of the Earth. In your model, how do the thicknesses of the lithosphere and crust compare? A The lithosphere is thinner than the crust. B The lithosphere is exactly the same thickness as the crust. C The lithosphere is thicker than the crust. D The lithosphere is thicker than the oceanic crust, but thinner than the continental crust. 4 Sequence the layers of the Earth in order from the exterior surface to the interior center. F Lithosphere, mantle, inner core, outer core, crust, asthenosphere G Inner core, outer core, mantle, asthenosphere, lithosphere, crust H Crust, mantle, outer core, inner core, asthenosphere, lithosphere J Crust, lithosphere, asthenosphere, mantle, outer core, inner core Page 4 GO ON 5 The tectonic plate labeled A in the diagram is the A Eurasian Plate B Indo-Australian Plate C Pacific Plate D African Plate Page 5 GO ON 6 The tectonic plate labeled B in the diagram is the — F Eurasian Plate G Indo-Australian Plate H Pacific Plate J North American Plate Page 6 GO ON Directions: The map below shows Earth's tectonic plates; six of them are numbered. -

Related Magmatism in the Upper Wind River Basin, Wyoming (USA), GEOSPHERE; V

Research Paper THEMED ISSUE: Cenozoic Tectonics, Magmatism, and Stratigraphy of the Snake River Plain–Yellowstone Region and Adjacent Areas GEOSPHERE The leading wisps of Yellowstone: Post–ca. 5 Ma extension- related magmatism in the upper Wind River Basin, Wyoming (USA), GEOSPHERE; v. 14, no. 1 associated with the Yellowstone hotspot tectonic parabola doi:10.1130/GES01553.1 Matthew E. Brueseke1, Anna C. Downey1, Zachary C. Dodd1, William K. Hart2, Dave C. Adams3, and Jeff A. Benowitz4 12 figures; 2 tables; 1 supplemental file 1Department of Geology, Kansas State University, 108 Thompson Hall, Manhattan, Kansas 66506, USA 2Department of Geology and Environmental Earth Science, Miami University, 118C Shideler Hall, Oxford, Ohio 45056, USA 3Box 155, Teton Village, Wyoming 83025, USA CORRESPONDENCE: brueseke@ ksu .edu 4Geophysical Institute and Geochronology Laboratory, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775, USA CITATION: Brueseke, M.E., Downey, A.C., Dodd, Z.C., Hart, W.K., Adams, D.C., and Benowitz, J.A., 2018, The leading wisps of Yellowstone: Post–ca. 5 Ma ABSTRACT the issue of linking volcanic events to a specific driving mechanism (Fouch, extension-related magmatism in the upper Wind River 2012; Kuehn et al., 2015). Complicating matters, magmatism often continues Basin, Wyoming (USA), associated with the Yellow- The upper Wind River Basin in northwest Wyoming (USA) is located ~80– long after (e.g., millions of years) the upper plate has been translated away stone hotspot tectonic parabola: Geosphere, v. 14, no. 1, p. 74–94, doi:10.1130/GES01553.1. 100 km southeast of the Yellowstone Plateau volcanic field. While the upper from an upwelling plume (Bercovici and Mahoney, 1994; Sleep, 2003; Shervais Wind River Basin is a manifestation of primarily Cretaceous to Eocene Lara- and Hanan, 2008; Jean et al., 2014). -

The Track of the Yellowstone Hot Spot: Volcanism, Faulting, and Uplift

Geological Society of America Memoir 179 1992 Chapter 1 The track of the Yellowstone hot spot: Volcanism, faulting, and uplift Kenneth L. Pierce and Lisa A. Morgan US. Geological Survey, MS 913, Box 25046, Federal Center, Denver, Colorado 80225 ABSTRACT The track of the Yellowstone hot spot is represented by a systematic northeast-trending linear belt of silicic, caldera-forming volcanism that arrived at Yel- lowstone 2 Ma, was near American Falls, Idaho about 10 Ma, and started about 16 Ma near the Nevada-Oregon-Idaho border. From 16 to 10 Ma, particularly 16 to 14 Ma, volcanism was widely dispersed around the inferred hot-spot track in a region that now forms a moderately high volcanic plateau. From 10 to 2 Ma, silicic volcanism migrated N54OE toward Yellowstone at about 3 cm/year, leaving in its wake the topographic and structural depression of the eastern Snake River Plain (SRP). This <lo-Ma hot-spot track has the same rate and direction as that predicted by motion of the North American plate over a thermal plume fixed in the mantle. The eastern SRP is a linear, mountain- bounded, 90-km-wide trench almost entirely(?) floored by calderas that are thinly cov- ered by basalt flows. The current hot-spot position at Yellowstone is spatially related to active faulting and uplift. Basin-and-range faults in the Yellowstone-SRP region are classified into six types based on both recency of offset and height of the associated bedrock escarpment. The distribution of these fault types permits definition of three adjoining belts of faults and a pattern of waxing, culminating, and waning fault activity. -

Discovery of Two New Super-Eruptions from the Yellowstone Hotspot Track (USA): Is the Yellowstone Hotspot Waning? Thomas R

https://doi.org/10.1130/G47384.1 Manuscript received 13 January 2020 Revised manuscript received 16 April 2020 Manuscript accepted 16 April 2020 © 2020 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Published online 1 June 2020 Discovery of two new super-eruptions from the Yellowstone hotspot track (USA): Is the Yellowstone hotspot waning? Thomas R. Knott1, Michael J. Branney1, Marc K. Reichow1, David R. Finn1, Simon Tapster2 and Robert S. Coe3 1 School of Geography, Geology and the Environment, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK 2 British Geological Survey, Nottingham NG12 5GG, UK 3 Earth and Planetary Science Department, University of California–Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, California 95064, USA ABSTRACT Super-Eruption Recognition Super-eruptions are amongst the most extreme events to affect Earth’s surface, but too few Recognizing a super-eruption requires quan- examples are known to assess their global role in crustal processes and environmental impact. tification of the dense rock equivalent (DRE) We demonstrate a robust approach to recognize them at one of the best-preserved intraplate volume of the erupted deposit (Pyle, 2000). large igneous provinces, leading to the discovery of two new super-eruptions. Each generated However, several similar deposits may coexist huge and unusually hot pyroclastic density currents that sterilized extensive tracts of Idaho in a succession, presenting a challenge to dis- and Nevada in the United States. The ca. 8.99 Ma McMullen Creek eruption was magnitude tinguish and correlate individual deposits. Suc- 8.6, larger than the last two major eruptions at Yellowstone (Wyoming). -

Mantle Dynamics and Characteristics of the Azores Plateau

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 362 (2013) 258–271 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Mantle dynamics and characteristics of the Azores plateau C. Adam a,n, P. Madureira a,b, J.M. Miranda c, N. Lourenc-o c,d, M. Yoshida e, D. Fitzenz a,1 a Centro de Geofı´sica de E´vora/Univ. E´vora, 7002-554 E´vora, Portugal b Estrutura de Missao~ para a Extensao~ da Plataforma Continental (EMEPC), 2770-047, Pac-o d’ Arcos, Portugal c Instituto Portugues do Mar e da Atmosfera, Lisboa, Portugal d University of Algarve, IDL, Campus de Gambelas, 8000 Faro, Portugal e Institute for Research on Earth Evolution (IFREE), Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), Yokosuka, Kanagawa 237-0061, Japan article info abstract Article history: Situated in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, the Azores plateau is a region of elevated topography Received 25 July 2012 encompassing the triple junction between the Eurasian, Nubian and North American plates. The plateau is Received in revised form crossed by the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and the Terceira Rift is generally thought of as its northern boundary. 2 November 2012 The origin of the plateau and of the Terceira Rift is still under debate. This region is associated with active Accepted 5 November 2012 volcanism. Geophysical data describe complex tectonic and seismic patterns. The mantle under this region Editor: T. Spohn Available online 18 January 2013 is characterized by anomalously slow seismic velocities. However, this mantle structure has not yet been used to quantitatively assess the influence of the mantle dynamics on the surface tectonics. -

Educators Guide

EDUCATORS GUIDE 02 | Supervolcanoes Volcanism is one of the most creative and destructive processes on our planet. It can build huge mountain ranges, create islands rising from the ocean, and produce some of the most fertile soil on the planet. It can also destroy forests, obliterate buildings, and cause mass extinctions on a global scale. To understand volcanoes one must first understand the theory of plate tectonics. Plate tectonics, while generally accepted by the geologic community, is a relatively new theory devised in the late 1960’s. Plate tectonics and seafloor spreading are what geologists use to interpret the features and movements of Earth’s surface. According to plate tectonics, Earth’s surface, or crust, is made up of a patchwork of about a dozen large plates and many smaller plates that move relative to one another at speeds ranging from less than one to ten centimeters per year. These plates can move away from each other, collide into each other, slide past each other, or even be forced beneath each other. These “subduction zones” are generally where the most earthquakes and volcanoes occur. Yellowstone Magma Plume (left) and Toba Eruption (cover page) from Supervolcanoes. 01 | Supervolcanoes National Next Generation Science Standards Content Standards - Middle School Content Standards - High School MS-ESS2-a. Use plate tectonic models to support the HS-ESS2-a explanation that, due to convection, matter Use Earth system models to support cycles between Earth’s surface and deep explanations of how Earth’s internal and mantle. surface processes operate concurrently at different spatial and temporal scales to MS-ESS2-e form landscapes and seafloor features. -

S41598-020-76691-1 1 Vol.:(0123456789)

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Rifting of the oceanic Azores Plateau with episodic volcanic activity B. Storch1*, K. M. Haase1, R. H. W. Romer1, C. Beier1,2 & A. A. P. Koppers3 Extension of the Azores Plateau along the Terceira Rift exposes a lava sequence on the steep northern fank of the Hirondelle Basin. Unlike typical tholeiitic basalts of oceanic plateaus, the 1.2 km vertical submarine stratigraphic profle reveals two successive compositionally distinct basanitic to alkali basaltic eruptive units. The lower unit is volumetrically more extensive with ~ 1060 m of the crustal profle forming between ~ 2.02 and ~ 1.66 Ma, followed by a second unit erupting the uppermost ~ 30 m of lavas in ~ 100 kyrs. The age of ~ 1.56 Ma of the youngest in-situ sample at the top of the profle implies that the 35 km-wide Hirondelle Basin opened after this time along normal faults. This rifting phase was followed by alkaline volcanism at D. João de Castro seamount in the basin center indicating episodic volcanic activity along the Terceira Rift. The mantle source compositions of the two lava units change towards less radiogenic Nd, Hf, and Pb isotope ratios. A change to less SiO2-undersaturated magmas may indicate increasing degrees of partial melting beneath D. João de Castro seamount, possibly caused by lithospheric thinning within the past 1.5 million years. Our results suggest that rifting of oceanic lithosphere alternates between magmatically and tectonically dominated phases. Oceanic plateaus with a crustal thickness to 30 km cover large areas in the oceans and these bathymetric swells afect oceanic currents and marine life 1,2. -

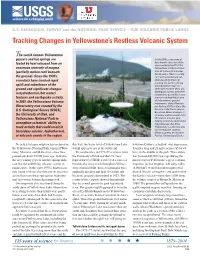

Tracking Changes in Yellowstone's Restless Volcanic System

U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY and the NATIONAL PARK SERVICE—OUR VOLCANIC PUBLIC LANDS Tracking Changes in Yellowstone’s Restless Volcanic System The world-famous Yellowstone geysers and hot springs are In the 1970s, a resurvey of benchmarks discovered the fueled by heat released from an unprecedented uplift of the enormous reservoir of magma Yellowstone Caldera of more (partially molten rock beneath than 28 inches (72 cm) over fi ve decades. More recently, the ground). Since the 1970’s, new and revolutionary sat- scientists have tracked rapid ellite-based methods for tracking the Earth’s shifting uplift and subsidence of the ground motions have en- ground and signifi cant changes abled University of Utah, U.S. Geological Survey, and other in hydrothermal (hot water) scientists to assemble a more features and earthquake activity. precise and detailed picture of Yellowstone’s ground In 2001, the Yellowstone Volcano movements. Global Position- Observatory was created by the ing System (GPS) stations like U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), this one in the Norris Geyser Basin can detect changes in the University of Utah, and elevation and horizontal shifts Yellowstone National Park to of 1 inch or less per year, helping scientists understand strengthen scientists’ ability to the processes that drive track activity that could result in Yellowstone’s active volcanic and earthquake systems. hazardous seismic, hydrothermal, (Photo courtesy of Christine or volcanic events in the region. Puskas, University of Utah.) No actual volcanic eruption has occurred in this way, the water level of Yellowstone Lake lowstone Caldera, a shallow, oval depression, the Yellowstone National Park region of Wyo- would appear to rise at the south end. -

R. L. Smith, H. R. Shaw, R. G. Luedke, and S. L. Russell U. S. Geological

COMPREHENSIVE TABLES GIVING PHYSICAL DATA AND THERMAL ENERGY ESTIMATES FOR YOUNG IGNEOUS SYSTEMS OF THE UNITED STATES by R. L. Smith, H. R. Shaw, R. G. Luedke, and S. L. Russell U. S. Geological Survey OPEN-FILE REPORT 78-925 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with Geological Survey Standards and nomenclature INTRODUCTION This report presents two tables. The first is a compre hensive table of 157 young igneous systems in the western United States, giving locations, physical data, and thermal en ergy estimates, where apropriate, for each system. The second table is a list of basaltic fields probably less than 10,000 years old in the western United States. These tables are up dated and reformatted from Smith and Shaw's article "Igneous- related geothermal systems" in Assessment of geothermal re sources of the United States 1975 (USGS Circular 726, White and Williams, eds., 1975). This Open-File Report is a compan ion to Smith and Shaw's article "Igneous-related geothermal systems" in Assessment of geothermal resources in the United States 1978 (USGS Circular 790, Muffler, ed., 1979). The ar ticle in Circular 790 contains an abridged table showing only those igneous systems for which thermal estimates were made. The article also gives an extensive discussion of hydrothermal cooling effects and an explanation of the model upon which the thermal energy estimates are based. Thermal energy is calculated for those systems listed in table 1 that are thought to contribute significant thermal en ergy to the upper crust. As discussed by Smith and Shaw (1975), silicic volcanic systems are believed to be associated nearly always with high-level (<10 km) magma chambers.