Don't Call Me Professor!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Princess Diana, the Musical Inspired by Her True Story

PRINCESS DIANA, THE MUSICAL INSPIRED BY HER TRUE STORY Book by Karen Sokolof Javitch and Elaine Jabenis Music and Lyrics by Karen Sokolof Javitch Copyright © MMVI All Rights Reserved Heuer Publishing LLC, Cedar Rapids, Iowa Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that this work is subject to a royalty. Royalty must be paid every time a play is performed whether or not it is presented for profit and whether or not admission is charged. A play is performed any time it is acted before an audience. All rights to this work of any kind including but not limited to professional and amateur stage performing rights are controlled exclusively by Heuer Publishing LLC. Inquiries concerning rights should be addressed to Heuer Publishing LLC. This work is fully protected by copyright. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission of the publisher. Copying (by any means) or performing a copyrighted work without permission constitutes an infringement of copyright. All organizations receiving permission to produce this work agree to give the author(s) credit in any and all advertisement and publicity relating to the production. The author(s) billing must appear below the title and be at least 50% as large as the title of the Work. All programs, advertisements, and other printed material distributed or published in connection with production of the work must include the following notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Heuer Publishing LLC of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.” There shall be no deletions, alterations, or changes of any kind made to the work, including the changing of character gender, the cutting of dialogue, or the alteration of objectionable language unless directly authorized by the publisher or otherwise allowed in the work’s “Production Notes.” The title of the play shall not be altered. -

Smokey Stumps in State, to Be Mugwump Candidate

Our Price — 10c Cheap A)! the news By all the fits thai fits ... that write it. rOLUME LV Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia. Friday, April 4. 1969 25 "Death" Wilson To Be Smokey Stumps In State, MI Cadet Of Year To Be Mugwump Candidate Second "classman Kenneth R. to go to Africa and "take up the i Wilson has been chosen by the white man's burden" while enjoy- LEXINGTON (Tass)—Democra- VMI, Public Relations Office as ing himself killing the local inhab- tic Party powers were rocked yes- VMI's cadet of the year. Wilson's itants. terday as famed Lexington politi- picture will now replace the statue Excusing himself from the ques- cian B. McCluer Gilliam declared of Virginia Mourning Her Dead on tioning Wilson went over to the his intentions to run in the upcom- the crest of all official Institute window where he blasted, with his ing party gubernatorial primary. publications .357 magnum, a butterfly who's "The time has come for Virginia In the words of the PRO, Wil- noisy flapping had distrubed him. to wake up!" the beloved VMI pro- son best exemplities the ViSII Returning to the interviev/, fessor said, slamming a book onto ideals—he is the Institute's model Death exclaimed that killing had the floor and waking up a few re- cadet. Wilson has so adapted him- always been part of his life—when porters who were nodding in the self to the VMI life that he can four days old, he had beaten his back row. "We must stick to ths truly say "I love it here." Bar- nurse to death with a jar of Beech- subject ot the course," he said, re- racks is not merely his home away nt baby food. -

Download 1 File

Starship Troopers by Robert Heinlein Table of Contents Starship Troopers Chapter 8 Chapter 1 Chapter 9 Chapter 2 Chapter 10 Chapter 3 Chapter 11 Chapter 4 Chapter 12 Chapter 5 Chapter 13 Chapter 6 Chapter 14 Chapter 7 Chapter 1 Come on, you apes! You wanta live forever? — Unknown platoon sergeant, 1918 I always get the shakes before a drop. I’ve had the injections, of course, and hypnotic preparation, and it stands to reason that I can’t really be afraid. The ship’s psychiatrist has checked my brain waves and asked me silly questions while I was asleep and he tells me that it isn’t fear, it isn’t anything important — it’s just like the trembling of an eager race horse in the starting gate. I couldn’t say about that; I’ve never been a race horse. But the fact is: I’m scared silly, every time. At D-minus-thirty, after we had mustered in the drop room of theRodger Young , our platoon leader inspected us. He wasn’t our regular platoon leader, because Lieutenant Rasczak had bought it on our last drop; he was really the platoon sergeant, Career Ship’s Sergeant Jelal. Jelly was a Finno-Turk from Iskander around Proxima — a swarthy little man who looked like a clerk, but I’ve seen him tackle two berserk privates so big he had to reach up to grab them, crack their heads together like coconuts, step back out of the way while they fell. Off duty he wasn’t bad — for a sergeant. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

A Multi-Method Examination of Race, Class, Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Motivations for Participation in the Youtube-Based “It Gets Better Project”

A Multi-method Examination of Race, Class, Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Motivations for Participation in the YouTube-based “It Gets Better Project” Laurie Marie Phillips A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Daniel Riffe Daren Brabham Barbara Friedman George Noblit Terri Phoenix © 2013 Laurie Marie Phillips ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT LAURIE MARIE PHILLIPS: A Multi-method Examination of Race, Class, Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Motivations for Participation in the YouTube-based “It Gets Better Project” (Under the direction of Dr. Daniel Riffe) On September 15, 2010, Dan Savage and Terry Miller created a YouTube channel that turned into a global phenomenon: the “It Gets Better Project” (IGBP). This multi-method study employs: 1) Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA) to examine race, class, gender, and sexual orientation within IGBP videos; and 2) video chat-based in-depth interviews for determining participants’ motivations for IGBP participation and production of crowdsourced, social media-based strategic communication. Using sociologist Patricia Hill Collins’ “matrix of domination” as a theoretical framework for understanding structural, disciplinary, hegemonic, and interpersonal oppressions that led to the IGBP’s creation, video production, and video content, this empirical study draws from a sample of 21 videos and 20 interviews. MCDA findings reveal that participants presented a pared-back version of their own racial, class, gender, and sexual identities; projected their identities onto viewers; and created and perpetuated myths through their video narratives. -

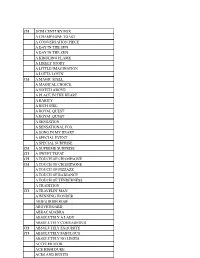

Saddlebred Sidewalk List.Docx

CH 20TH CENTURY FOX A CHAMPAGNE TOAST A CONVERSATION PIECE A DAY IN THE SUN A DAY IN THE SUN A KINDLING FLAME A LIKELY STORY A LITTLE IMAGINATION A LOTTA LOVIN' CH A MAGIC SPELL A MAGICAL CHOICE A NOTCH ABOVE A PLACE IN THE HEART A RARITY A RICH GIRL A ROYAL QUEST A ROYAL QUEST A SENSATION A SENSATIONAL FOX A SONG IN MY HEART A SPECIAL EVENT A SPECIAL SURPRISE CH A SUPREME SURPRISE CH A SWEET TREAT CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE A TOUCH OF PIZZAZZ A TOUCH OF RADIANCE A TOUCH OF TENDERNESS A TRADITION CH A TRAVELIN' MAN A WINNING WONDER ABIE'S IRISH ROSE ABOVE BOARD ABRACADABRA ABSOLUTELY A LADY ABSOLUTELY COURAGEOUS CH ABSOLUTELY EXQUISITE CH ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS ABSOLUTELY NO LIMITS ACCELERATOR ACE HIGH DUKE ACES AND EIGHTS ACE'S FLASHING GENIUS ACE HIGH DUKE ACES AND EIGHTS ACE'S FLASHING GENIUS ACE'S QUEEN ROSE ACE'S REFRESHMENT TIME ACE'S SOARING SPIRIIT ACE'S SWEET LAVENDER ACE'S TEMPTATION ACTIVE SERVICE ADF STRICTLY CLASS ADMIRAL FOX ADMIRAL'S AVENGER ADMIRAL'S BLACK FEATHER ADMIRAL'S COMMAND CH ADMIRAL'S FLEET CH ADMIRAL'S MARK CH ADMIRAL'S MARK ADMIRAL'S SHIPMATE CH ADVANTAGE ME CH ADVANTAGE ME AFFAIR OF THE HEART "JAKE" AFLAME AGLOW AGLOW AHEAD OF THE CLASS AIN'T MISBEHAVIN AIN'T MISBEHAVIN AIR OF ELEGANCE CH ALETHA STONEWALL ALEXANDER THE GREAT ALEXANDER'S EMERAUDE ALEXANDER'S EMERAUDE ALFIE ALICE LOU'S DENMARK CH ALISON MACKENZIE CH ALISON MACKENZIE CH ALL AMERICAN BOY ALL DRESSED UP ALL NIGHT LONG ALL ROSES ALL SHOW ALL THE MONEY ALLEGORY ALLIE COME LATELY "BAH" ALL'S CLEAR ALLSWEET ALLURING LADY ALONG CAME A SPIDER ALTERED IMAGE ALTON BELLE ALONG CAME A SPIDER ALTERED IMAGE ALTON BELLE CH ALVIN'S MR. -

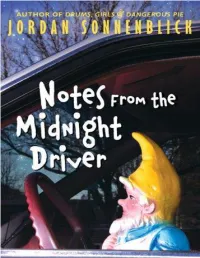

Notes from the Midnight Driver

Notes From the Midnight Driver Jordan Sonnenblick SCHOLASTIC INC. New York Toronto London Auckland Sydney Mexico City New Delhi Hong Kong Buenos Aires To my grandfather, Solomon Feldman, who inspired this book, and to the memory of my father, Dr. Harvey Sonnenblick, who loved it Table of Contents Title Page Dedication May Last September Gnome Run The Wake-Up Day Of The Dork-Wit My Day In Court Solomon Plan B Laurie Meets Sol Sol Gets Interested Half An Answer Happy Holidays The Ball Falls Happy New Year! Enter The Cha-Kings Home Again Am I A Great Musician, Or What? A Night For Surprises Darkness The Valentine’s Day Massacre Good Morning, World! The Mission The Saints Go Marchin’ In The Work Of Breathing Peace In My Tribe Finale Coda The Saints Go Marchin’ In Again Thank you Notes About the Author Interview Sneak Peek Copyright May Boop. Boop. Boop. I’m sitting next to the old man’s bed, watching the bright green line spike and jiggle across the screen of his heart monitor. Just a couple of days ago, those little mountains on the monitor were floating from left to right in perfect order, but now they’re jangling and jerking like maddened hand puppets. I know that sometime soon, the boops will become one long beep, the mountains will crumble into a flat line, and I will be finished with my work here. I will be free. LAST SEPTEMBER GNOME RUN It seemed like a good idea at the time. Yes, I know everybody says that—but I’m serious. -

The Gentleman Dancing-Master. by WILLIAM WYCHERLEY "Non Satis Est Risu Diducere Rictum Auditorus: Et Est Quædam Tamen

The Gentleman Dancing-Master. BY WILLIAM WYCHERLEY "Non satis est risu diducere rictum Auditorus: et est quædam tamen his quoque virtus."[51]--HORAT. If we may trust the author's statement to Pope, this admirable comedy was written when Wycherley was twenty-one years of age, in the year 1661-2. It is impossible to fix with certainty the date of its first performance. The Duke's Company, then under the management of the widow of Sir William Davenant, opened its new theatre in Dorset Gardens, near Salisbury Court, on the 9th of November, 1671, with a performance of Dryden's Sir Martin Mar-all, and Wycherley's "Prologue to the City" points to the production of his play in the new theatre shortly after its opening. Genest states, on the authority of Downes, that "The Gentleman Dancing-Master was the third new play acted at this theatre, and that several of the old stock plays were acted between each of the new ones." Sir Martin Mar-all, having been three times performed, was succeeded by Etherege's Love in a Tub, which, after two representations, gave place to a new piece, Crowne's tragedy of Charles the Eighth. This was played six times in succession, and was followed, probably after an interval devoted to stock pieces, by a second novelty, an adaptation by Ravenscroft from Molière, entitled The Citizen turn'd Gentleman, or Mamamouchi, which ran for nine days together. The Gentleman Dancing-Master was then acted, probably after another short interval, and must therefore have been produced either in December, 1671, or in January, 1672. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 15/10/2018 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 15/10/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry Someday You'll Want Me To Want You Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Blackout Heartaches I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET Other Side Cheek to Cheek Aren't You Glad You're You 10 Years My Romance (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha No Love No Nothin' 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together Personality Because The Night Kumbaya Sunday, Monday Or Always 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris This Heart Of Mine Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are Mister Meadowlark I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes 1950s Standards The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine Get Me To The Church On Time Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Fly Me To The Moon Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter Crawdad Song Cupid Body And Soul Christmas In Killarney Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze That's Amore 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In Organ Grinder's Swing 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Lullaby Of Birdland Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Rags To Riches Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Something's Gotta Give 1800s Standards I Thought About You I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus (Man -

RESPONDER July 2018.Indd

JULY 2018 Chautauqua County Offi ce of Volume 18 Number 1 EMERGENCY SERVICES 23rd Annual Chautauqua County Ronald J. Keddie Memorial Weekend SEPTEMBER 7 – 9, 2018 • Exciting and educational classes with a great CME program for EMT’s, avoid the traditional NYS EMT test with CME’s. • First year classes with the Live Burn Rail Car Simulator, High Hazard Train fi res • Fire Alarm Systems and Fire Sprinkler Systems for the Fire Service • Rescue Ropes Operations in Service Training • Alternative Fueled Vehicles and New Vehicle Technology, The Firefi ghters Guide to Lightweight Construction, Fire Reporting Workshop, Courage to be Safe • Classes for all Fire Personnel, something for everyone SPECIAL EVENTS Friday Night: Food at the Moose Lodge Saturday Night: Hawaiian Party with Dinner & Music Bring your Hawaiian Shirt and be ready to have fun — NEW FOR 2018 — $100 in Lottery Tickets for the Department with the most attendees $50 in Lottery Tickets for the Department with the most NEW attendees For more information, Contact the Offi ce of Emergency Services 753-4341 or mail to:contactus@chautcofi re.org John Griffi th, Director of Emergency Services. IN THIS ISSUE: 11-12 Training keeps the Hazardous Materials 2-4 Fredonia Fire Boldly Goes to Response Team Busy New Department Structure 12 President Julius J. Leone Jr. 4 Chaplins Corner 13 New Engine for Lily Dale 5 Hazardous Materials Team Participates in 14-15 23rd Annual Chautauqua County WNY Traning/Drill at Phosgene Plant Ronald J. Keddie Memorial Weekend 6 County Hazmat Resources Called to Assist 16 County Weekend 2018-CME Camp Schedule Ashville Fire 17-22 Information Bulletin Training Trivia 22 Notes from the Editor 7 National Recognition For Ray L. -

Chapter 1: Parts of Speech Overview, Pp. 1–25

L09NAGUMA10_001-012.qxd 12/11/07 2:28 PM Page 1 Chapter 1: Parts of Speech 14. Leslie always lapses into baby talk when Overview, pp. 1–25 she sees a litter of kittens. Common, Proper, Concrete, and Abstract Nouns, 15. The band included one song that sounded as p. 1 if it had been recorded in an echo chamber. EXERCISE Com, A [or Con] 16. The class presented Ms. Stockdale with a 1. A constitution may have a bill of rights. bouquet of baby’s breath. 2. The Constitution of the United States guar- Com, A 17. The TV weatherperson explained to the antees freedomof speech. P, Con audience how a barometer works. 3. The Works Progress Administration existed 18. In order to get a good batch of cookies, you during the Great Depression. need to use the best oatmeal available. 4. That candidate is a staunch supporter of a Com, A [or Con] 19. A school of killer whales followed in the republican form of government. P, Con wake of the ship. 5. The Articles of Confederation were y of the instructor. 20. The bird-watchers were awe-struck as the approved in 1781. flock of geese lifted into the sky. 6. This document established “a firm league Com, A of friendship” among the states. Pronouns and Antecedents, p. 3 Com, Con Possessive pronouns in items 1 and 3, Ex. A, and 7. The editorial in today’s newspaper items 14 and 15, Ex. B, also may be identified as defended the proposed amendment. possessive adjectives. P, Con 8. -

October 2012

The Poly Optimist John H. Francis Polytechnic High School Vol. xcviii, No. 3 Serving the Poly Community Since 1913 October 2012 Romney Gains Edible Incentives Ground Perfect attendance By Nam Woo equals pizza party. Staff Writer and Fridays. By Yesenia Carretero & Javier Valdez Republican presidential nominee Staff Writers “We can have books, computers, Mitt Romney turned in a surprisingly fun activities, resources, and copies,” strong performance in the first of Munguia said, “but all of that costs three presidential debates last week. Parrots in five classrooms money. When students miss school, President Obama, on the other recently ate free doughnuts we don’t get the money we were hand, seemed listless and uninter- under Poly’s new Attendance supposed to get from the state.” For example, in August 2011 Poly ested. Improvement Program. The Minutes in to the debate, Tweets, lost $57,522.00 because of absences. Facebook and TV reporters had only catch: 10 days of perfect This year Poly lost $26,129.00 attendance. although. In September 2011 we lost Romney as the winner and Barack Photo by Jasmine Guevara as ineffective, almost immediately $69,835.00 and this year we only AND THE WINNER IS: Idol winner Crystal Cruz (right) and runner up changing Romney’s status from be- “The classes are always very lost $53,163.00, so attendance is Audri Wilson react to the announcement of the voting for Poly Idol. hind in the polls to neck and neck. excited,” said Pupil Service better. The challenger used the debate Attendance (PSA) Counselor An absence without a note is to attack Obama on health care, jobs Maribel Munguia.