Final Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pincode Officename Statename Minisectt Ropar S.O Thermal Plant

pincode officename districtname statename 140001 Minisectt Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Thermal Plant Colony Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Ropar H.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Morinda S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140101 Bhamnara B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Rattangarh Ii B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Saheri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Dhangrali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Tajpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Lutheri S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Rollumajra B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Kainaur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Makrauna Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Samana Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Barsalpur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Chaklan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Dumna B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140103 Kurali S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Allahpur B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Burmajra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Chintgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Dhanauri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Jhingran Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Kalewal B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Kaishanpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Mundhon Kalan B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sihon Majra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Singhpura B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sotal B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Sahauran B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140108 Mian Pur S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Pathreri Jattan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Rangilpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Sainfalpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Singh Bhagwantpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Kotla Nihang B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140108 Behrampur Zimidari B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Ballamgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Purkhali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140109 Khizrabad West S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140109 Kubaheri B.O Mohali PUNJAB -

Guru Har Sahai Block Firozpur District

GURU HAR SAHAI BLOCK M A M D O T B L O C K FIROZPUR DISTRICT BAHADUR KE CHAK SARKAR 301 MEGA BORDER VILLAGES MAP BAHADARKE MEHTAM CHAK SOMIAN KOAR 306 326 WALA SINGH WALA CHAK CHHANGA 239 238 CHAK MEGHA DONA MAHTAM BAHADAR KE MAHANTAN 308 CHAK JAMIAT 307 CHHANGA 325 BAJA KE SINGH WALA RAI HITHAR 300 309 237 MARE ® BOOLA MAHTAM CHHANGA KALAN N DONA HITHAR MAHATAM 0 1.5 3 6 A PINDI 166 F T KHUNG KE 310 298 312 BOOLA MAHTAM 169 A S MARE I MEGHA PANJ UTTAR NAUNARI VIRAK Kilometers K KHURD R DONA GRAIN HITHAR 297 KHOKHER UTTAR WASAL KHURD A DONA GUDAR 167 I P BHADRU 311 MEGHA PANJ 299 MOHAN KE 165 PANJ GRAIN D 318 314 PANJE GRAIN UTTAR 170 GUDDAR KE HITHAR 295 MOHAN K HAJI KE HITHAR PANJ GRAIN 316 MOHAN KE O RANA ISSA PANJ BETTU 172 317 PANJE UTTAR GRAIAN 296 MANDI T KE UTTAR 168 320 SAIDO WALA CHUGA 294 KE MOHAN 171 164 D 173 GURU ISSA NAUBRAMAD SHER SINGH CHAK HAR SAHAI I PANJ GRAIN RUKNA QUTAB SHER SINGH WAL WALA PANJE KE 162 S 287 BODLA GARH BAGUWALA 327 326 SWAYA 288 JIWAN T SWAYA MATTAM UTTAR 293 ARAIN 174 NIDHANA 163 MAHTAM HITHAR RAHIM SHAH R N 286 TILU 292 175 A GATI AJAIB 322 NURE KEBODLA I BILLIMAR ARAIN CHAK T SINGH WALA 285 276 C 324 289 NIDHANA S 331 SHEKH T I KHERE KHERE 177 SHATIA K KE HITHAR SHAMAN PIR KE KE UTTAR KUTTI WALA A BALE 325 277 MALIK THETHERAN 155 HITHAR DULLE KE 284 SULLAH 176 P KE UTTAR TRIPAL KE ZADA WALA 341 NATH WALA GHULLAH 279 337 BADAL THARA SINGH 290 291 182 MEHMOOD KHANEKE 330 280 KE HITHAR WALA HITHAR BHURAN PIRKE 342 BAME 333 335 MAHANTAN MOTHANWALA WALA BHATTI BODLA DULE KE BADAL KE GURU HAR SAHAI -

Teachers State Award

rwj AiDAwpk purskwr 2018 sn Name, designation, school name and district 1 Saurabh Manro, GMS Khatra, Sc Master Ludhiana 2 Kulwinder Singh, GSSS bibipur, Math Master Ludhiana 3 Darshan Singh, GMS Rajgarh, SST Master Ludhiana 4 Jagriti Gour, GSSS Lalori Kalan, Lec English Ludhiana 5 Nisha Rani, HT, GPS Gaispura Ludhiana 6 Harbhupinder Kaur, Principal, GSSS Haibowal Khurd Ludhiana 7 Harmeet Singh, GSSS Bhakna Kalan, Lec Political Science, Amritsar 8 Surjit Singh, GHS Shahura, SStg Master Amritsar 9 Harjinder Pal, GSSS M.S. Road, SSt Master Amritsar 10 Tajinder Singh, GPS Ludhar, HT Amritsar 11 Gurmeet Singh, Lec Political Sc, GSSS Rangar Nangal Gurdaspur 12 Ladwinder Kaur, GPS Daburji, ETT Gurdaspur 13. Ravinder Singh, GPS Nawan Pind Bahadur, JBT Gurdaspur 14. Ravinder Singh Kang, GPS Chuhar, Jalandhar 15 Lakhwinder Singh, GPS Khanpura Dhadda, ETT Jalandhar 16 Harbhajan Singh, Lec political, GSSS Basti Mithu, Jalandhar 17 Raj Kumar, GPS Cheema kalan, HT Jalandhar 18 Paras Kumar, GPS Gatti Rahime ke, CHT Firozpur 19 Vipan Kumar, GPS Basti Dunne wai Firozpur 20 Sanjeev Kumar Sharma, Lecturer, GSSS Ulana, Msc Chemistry Patiala 21 Amritpal Kaur, Msc, Math Master, GSSS Model Town, Patiala 22 Sohan Lal, GSSS Fatehgarh Channa, SST Master Patiala 23 Ramesh Kumar, GHS Bhutal Khurd, Master Punjabi, Sangrur 24 Sukhchain Singh, Sc Master, GSSS Sheron, Sangrur 25 Kuldeep Singh, H/M, GHS Kheri, Sangrur 26 Rajnish Kumar, GSSS Hajipur, Lec English Hoshiarpur 27 Lalita Rani, GSSS (G) Railway Mandi Hoshiarpur 28 Armanpreet Singh, GSSS Birampur, Lec Punjabi Hoshiarpur 29 Sukhjit Singh, GSSS Balianwali, Lec Pbi Bathinda 30 Seema Rani, GPS Rampura Vill, ETT Bathinda 31 Gurlovedeep singh, HT, GPS Tharu Taran Taran 32 Kuldeep Kaur, Lect bio Gogabua Taran Taran 33 Gaurav Sharma, GPS Karyal, JBT/ETT, Moga 34 Dilbag Singh Brar, GSSS GTB Garh, Moga 35 Anshul Jain, Sc Mistress, GSSS Jarraut Mohali 36 Avani Paul, H/M Ramgarh Rurki Mohali 37 Hari Bhagan Priyadarshi, Lecturer, GSSS (G) w.no. -

Of Indian Railways. The

INTRODUCTION Firozpur Division is one of the five Railway Divisions under Northern Railway Zone (NR) of Indian Railways. The Division, with a route kilometerage of approximately 1849.95 kms (1685.64 BG + 164.31 NG- Corrected up to 31/03/2018) and 235 stations caters to the Rail Transport needs of Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir and a part of Himachal Pradesh. Firozpur Division serves a large number of industrial and important towns like Amritsar, Jalandhar, Hoshiarpur, Ludhiana, Firozpur and Kapurthala in Punjab and Kangra, Palampur, Baijnath Paprola and Joginder Nagar in Himachal Pradesh. Firozpur is also an important Division for freight traffic the main commodities loaded been food grains, Petroleum Products, Cotton, Machinery and Components. Inward traffic comprises Iron and Steel, Fertilizer, Coal, Petroleum Products and Cement. Sections of Firozpur Division: Following are the sections of Firozpur Division: 1. SNL-LDH-JUC-ASR- 150.65 KM. (24 STATIONS) 2. JUC/JRC-PTK/PTKC-JAT- 215.28 KM. (30 STATIONS) 3. JAT-KATRA-77.96 KM. (8 STATIONS) 4. FZR-BTI-87.35 KM. (14 STATIONS) 5. FZR-LDH -123.95 KM. (20 STATIONS) 6. FKA-FZR- 88.09 KM. (14 STATIONS) 7. FKA-ABS- 42.89 KM. (7 STATIONS) 8. JUC-NRO- 31.90 KM. (6 STATIONS) 9. FZR-JUC- 117.42 KM. (18 STATIONS) 10. PHR-LNK- 72.42 KM. (13 STATIONS) 11. JUC-JRC-HSX- 42.92 KM. (7 STATIONS) 12. BES-TTO- 48.58 KM. (8 STATIONS) 13. ASR-DBNK- 53.54 KM. (9 STATIONS) 14. ASR-ATT- 25.21 KM. (4 STATIONS) 15. BAT-QDN- 19.44 KM. -

MINISTRY of ROAD TRANSPORT and HIGHWAYS Through Punjab PWD B&R

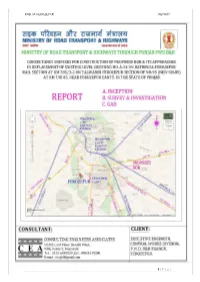

Project Report for Forest Department MINISTRY OF ROAD TRANSPORT AND HIGHWAYS Through Punjab PWD B&R CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR PREPARATION OF FEASIBILITY SURVEY, DETAILED PROJECT REPORT OF EXISTING TWO LANE PLUS SHOULDER TO (4-LANING OF TALWANDI BHAI TO FEROZEPUR KM: 170.00 TO 194.00 OF NEW NH-5 (OLD NH-95) IN THE STATE OF PUNJAB) TO BE EXECUTED ON EPC MODE. PROJECT REPORT Submitted by: THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER Central works Division, Punjab PWD (B&R), Ferozepur Page 1 - Project Report for Forest Department Table of Contents Description Page No Chapter – 1 INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 1.1 General………………….……………………………………………………………………………………… 3 1.2 Punjab State at a Glance ………………………………………………………………………..…….… 3 1.2.1 Ferozepur District at a Glance………………………………………………………………….. 5 1.2.1.1 Area………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Chapter-2 Proposal 2.1 General……………………………………………………………………………………………. 7 2.2 Proposals .............................................................................................. 7 Estimate .............................................................................................................................. 8 Page 2 - Project Report for Forest Department Chapter -1 1.0 Introduction 1.1 General The Government of India has taken up a massive programme of up- gradation & development of National Highways. Under NH’s development project, hundreds of kilometres have been proposed to be widened to 4/6 lane depending up on the traffic volume. These National Highways would provide high speed connectivity. NH-95 (0ld) renamed as NH-05 (new) is one of the road under this programme. For the purpose of project preparation, various corridors have been divided into convenient sections, selected on the basis of traffic generation and attraction potential, geographic location and other considerations. This report deals with converting this section from Km. 170.00 (Talwandi Bhai) to Km. -

Jauhar Quarterly Newsletter Vol4 Issue2

G 9 Faculties G 39 Departments G 27 Centres of Excellence and Research G 238 Courses G 991 Faculty Members G Over 16,500 Undergraduate, Post-Graduate and Diploma/Certificate Students Contents Maulana Mohamed Ali ‘Jauhar’ Founder, Jamia Millia Islamia From the Officiating Vice-Chancellor IN FOCUS Of human bonds Jamia’s green brigade Author Asghar Wajahat’s impressions of Jamia since 1971 ......................................................... Work that researchers are doing for environment in 22 are for environment requires scientific understanding of the processes around us. In order to various disciplines at Jamia ................................4 know how environmental degradation is happening, and how to mitigate the losses, scientific Also Cdata is required. At Jamia, researchers have been working diligently on understanding air, water ON CAMPUS and soil pollution and are engaged in developing appropriate technologies for environment protection. COURSE OF ACTION Happenings in Jamia Our green research is not confined to sciences. Social science researchers are working on policy and Dental pride .................................. 8 legal aspects of environment, working on global green politics and response of communities by way of The Faculty of Dentistry has developed enviable course correction. This issue of Jauhar is devoted to the green cause (read our Lead Story ‘Jamia’s infrastructure in just five years ........................14 FACULTY PROFILE Green Brigade’). Honours for Jamia Another area where Jamia is conscientiously working is gender sensitization. The Sarojini Naidu faculty................. 23 SPECIAL STORY Centre for Women’s Studies has brought the ‘One Billion Rising’ campaign — started by noted activist Kishanganj experiment author Eve Ensler — to the campus. Eve Ensler visited the campus in December 2013 and gave a mov - ing performance. -

Annexure – H 2 Format for Advertisement in Website Notice For

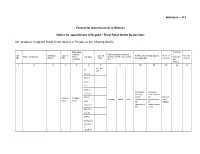

Annexure – H 2 Format for Advertisement in Website Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships IOC proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Punjab, as per following details: Estimated Fixed Fee monthly Minimum Dimension (in / Sl. Revenue Type of Type of Finance to be arranged by Mode of Security Name of location Sales Category M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. Minimum No District RO Site* the applicant Selection Deposit Potential M.). * Bid # amount 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 CC / DC / SC CFS SC CC-1 SC CC-2 SC PH ST ST CC-1 Estimated Estimated ST CC-2 working fund required capital for Draw of Regular / MS+HSD ST PH Frontage Depth Area requirement development Lots / Rural in Kls OBC for of Bidding OBC CC-1 operation of infrastructure RO at RO OBC CC-2 OBC PH OPEN OPEN CC-1 OPEN CC- 2 OPEN PH FROM KM STONE 11 TO KM STONE 20 ON NH-54 (OLD NH-15) LEFT HAND Draw of 1 PATHANKOT Regular 150 SC CFS 35 45 1575 0 0 0 3 SIDE (WHILE GOING lots FROM PATHANKOT TO AMRITSAR) FROM KM STONE 340 TO KM STONE 347 ON NH 44 (OLD NH 1A) RIGHT HAND Draw of 2 PATHANKOT Regular 160 SC CFS 35 45 1575 0 0 0 3 SIDE (WHILE GOING lots FROM MADHOPUR TO JALANDHAR) VILLAGE- BABRI ON NH Draw of 3 GURDASPUR Regular 150 SC CFS 35 45 1575 0 0 0 3 54 lots FROM KM STONE 365 TO KM STONE 370 ON NH 44 (OLD NH 1A) LEFT HAND Draw of 4 PATHANKOT Regular 150 SC CFS 35 45 1575 0 0 0 3 SIDE (WHILE GOING lots FROM PATHANKOT TO JALANDHAR) AMRITSAR CITY (WML) Draw of 5 ON TARN TARAN ROAD AMRITSAR Regular 160 SC CFS 15.24 18.29 278.74 0 0 0 3 lots LHS FROM KM -

1 | P a G E ROB at FEROZEPUR REPORT

ROB AT FEROZEPUR REPORT 1 | P a g e ROB AT FEROZEPUR REPORT Table of Contents S.NO. ABBREVIATIONS PAGE NO. 1 CHAPTER-1 (Introduction) 3-8 2 CHAPTER-2 (Detail of the Up-gradation History of 9-11 National Highway NH-5 (NH 95 old)) 3 CHAPTER-3 (Consultancy Services) 12-15 4 CHAPTER-4 (Quality Control & Quality Assurance) 16 5 CHAPTER-5 (Inception Report) 17-18 6 CHAPTER-6 (Proposal) 19-23 2 | P a g e ROB AT FEROZEPUR REPORT Chapter -1 Introduction 1.1 General The Government of India has taken up a massive programme of up- gradation & development of National Highways. Under NH’s development project, hundreds of kilometres have been proposed to be widened to 4/6 lane depending up on the traffic volume. These National Highways would provide high speed connectivity. NH-95 (0ld) renamed as NH-05 (new) is one of the road under this programme. For the purpose of project preparation, various corridors have been divided into convenient sections, selected on the basis of traffic generation and attraction potential, geographic location and other considerations. This report deals with construction of proposed ROB and its approaches in replacement of existing level crossing No.A-54/2-E, on Bathinda- Ferozepur rail section at km 381/1-2 & NH-95(new NH-05) section of Talwandi-Ferozepur road at km 198.05,near Ferozepur cantt in the state of Punjab. The total number of TVU at this Level Crossing was 161644 on 04-2011. The Level Crossing remains closed for about 20 times in a day & for most of the time causing traffic jams and inconvenience to the public. -

TABOR-DISSERTATION-2014.Pdf

Copyright by Nathan Lee Marsh Tabor 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Nathan Lee Marsh Tabor Certifes that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A Market for Speech Poetry Recitation in Late Mughal India, 1690-1810 Committee: Syed Akbar Hyder, Supervisor Kathryn Hansen Kamran Asdar Ali Gail Minault Katherine Butler Schofeld A Market for Speech Poetry Recitation in Late Mughal India, 1690-1810 by Nathan Lee Marsh Tabor, B.A.; M.Music. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfllment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2014 Acknowledgments Dissertations owe their existence to a community of people who support their authors and the awkward acknowledgments section does little to give enough credit where it’s due. Nonetheless, I tip my hat to the myriad people who helped me. Fieldwork was a long process with strange turns. Fellow tea-drinkers and gossips in Muzafarnagar were witty, sagacious, hospitable, and challenging companions who helped me to chart this project albeit indirectly. Though my mufassal phase only gets a nod in the present work, Muzafarnagar-folks’ insights and values informed my understanding of Urdu literature’s early history and taught me what to look for while wading through compendiums. Now the next project will be better prepared to tell their complicated and intriguing stories. Had it not been for Syed Akbar Hyder, my advisor and guide, there would be no “speech market.” He knew me, my strengths, hopefully overlooked my shortcomings, and put me on a path perfectly hewn for my interests. -

Jauhar Vol2 Issue3 March2012

N9 Faculties N37 Departments N27 Centres of Excellence and Research N231 Courses N642 Faculty Members NOver 15,000 Undergraduate, Post-Graduate and Diploma/Certificate Students Contents IN FOCUS Chronicler of Jamia A unique symbiosis Jamia alumnus Ghulam Haider has painstakingly recorded experiences of a cross-section of people What unique relationship does the ‘Central from the University .......................................... University’ Jamia enjoy with the community 22 around it? ............................................................4 Also COURSE OF ACTION ON CAMPUS The other media course Happenings in Jamia ...................8 While MCRC is renowned across the country for its ‘product’, the Hindi Department too offers FACULTY PROFILE courses in media................................................14 Faculty publications...............23 STUDENT ZONE A stint in Turkey A chance to work in the Turkish media; success in judicial services exams and IIT-JEE................ 16 Mother courage Girls from the walled city of Delhi create history by joining the 300-year-old, all-male Anglo-Arabic School .............................................................. 19 PAGE OUT OF THE PAST A professor, a kite seller Habib Tanvir first staged his Agra Bazaar in Jamia in 1954, casting Jamia professors and local villagers alike ..................................................20 Jauhar is published by The Registrar, Editorial Board: Jauhar is Printed by Enthuse-Answers Jamia Millia Islamia, Maulana Mohamed Simi Malhotra, Media Coordinator -

State Expert Appraisal Committee (SEAC) Punjab Agenda of 191St

State Expert Appraisal Committee (SEAC) Punjab Agenda of 191st meeting of State Expert Appraisal Committee (SEAC) AGENDA Venue: In the Conference Hall no. 2 at Ist Floor, MGSIPA Complex, Sector- 26, Chandigarh at 10:30 AM Please Check MoEF&CC Website at www.parivesh.nic.in for details and updates. Date:24 Jul 2020 AT 10:30 AM CONSIDERATION OF TOR PROPOSALS S.No Time Slot 10:40 AM Mining lease Located at Village Chabba, Tehsil Zira & District Ferozepur on the Agricultural Land having an area of 8.81 ha S. State District Tehsil Village (1) No. (1.) Punjab Firozpur Zira Chhaba [SIA/PB/MIN/52223/2020 , SEIAA/PB/MIN/ToR/2020/07 ] S.No Time Slot 10:55 AM Mining project at village Chugate wala ,Tehsil & District Feroepur having an area of 6.20 ha S. State District Tehsil Village (2) No. (1.) Punjab Firozpur Firozepur Chugate wala [SIA/PB/MIN/52385/2020 , SEIAA/PB/MIN/ToR/2020/01 ] S.No Time Slot 11:10 AM Mining site Located at Village Bulla, Tehsil Zira & District Ferozepur on the Agricultural Land having an area of 5.70 ha S. State District Tehsil Village (3) No. (1.) Punjab Firozpur Zira Bulla [SIA/PB/MIN/52432/2020 , SEIAA/PB/MIN/TOR/2020/02 ] S.No Time Slot 11:25 AM Mining lease Mamdot Uttar-1 Located at Village- Mamdot Uttar, Tehsil- (4) Ferozepur, District-Ferozepur, Punjab on the Agricultural Land having an area of 7.02 ha S. State District Tehsil Village No. (1.) Punjab Firozpur Firozepur Mamdot Uttar [SIA/PB/MIN/52767/2020 , SEIAA/PB/MIN/TOR/2020/03 ] S.No Time Slot 11:40 AM Mining site Located at Village Beri Qadrabad, Tehsil Zira & District Ferozepur on the Agricultural Land having an area of 1.60 ha S. -

Better Days Are Here Again

Invitation` Price50 May 31, 2014 ` 100 INDIA LEGALSTORIES THAT COUNT BETTERVERDICT 2014 DAYS ARE HERE AGAIN ARE THEY? DEMISE OF VOTE BANKS? WHY MUSLIMS ARE NOT SCARED HOPE vs HYPE MODINAMA: BIOGRAPHIES AND COMICS HONEYMOON PERIOD: NO IFs AND BUTs GANGES CATCHES FIRE POLITICO-TOONS MAY 31, 2014 VOLUME. VII ISSUE. 18 Editor-in-Chief Inderjit Badhwar LEAD / THE NATION / MANDATE 2014 Managing Editor Ramesh Menon Executive Editor Start of an era Alam Srinivas Taking Varanasi as the metaphor, INDERJIT BADHWAR delivers a Senior Editor firsthand account of how the ancient city represented the country’s 4 Vishwas Kumar Contributing Editors need for change, and made it possible Naresh Minocha, Girish Nikam Associate Editor Meha Mathur Deputy Editors Prabir Biswas, Vishal Duggal Deputy Art Director Anthony Lawrence Graphic Designer Lalit Khitoliya Photographer Anil Shakya News Coordinator Kh Manglembi Devi Production Pawan Kumar Verma CFO Anand Raj Singh VP (HR & General Administration) Lokesh C Sharma Director (Marketing) Raju Sarin GM (Sales & Marketing) Naveen Tandon-09717121002 No longer a political bogeyman DGM (Sales & Marketing) Feroz Akhtar-09650052100 Modi’s election campaign was far less divisive than feared. 14 Marketing Associate INDERJIT BADHWAR contends that the new PM can bring about a Ggarima Rai fundamental shift in the way the state treats its citizens, including minorities For advertising & subscription queries [email protected] A tectonic change Published by Raju Sarin on behalf of E N Communications Pvt Ltd and printed at This election transformed the nation’s political trajectory like never before, CIRRUS GRAPHICSPvt Ltd., B-61, Sector-67, Noida. (UP)- 201 301 (India) making old paradigms redundant.