The-Atvotzkers.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wedding Customs „ All Piskei Horav Yisroel Belsky Shlita Are Reviewed by Horav Yisroel Belsky Shlita

Halachically Speaking Volume 4 l Issue 12 „ Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits „ Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita Wedding Customs „ All Piskei Horav Yisroel Belsky Shlita are reviewed by Horav Yisroel Belsky Shlita Lag B'omer will be upon us very soon, and for this is because the moon starts getting people have not been at weddings for a while. smaller and it is not a good simon for the Therefore now is a good time to discuss some chosson and kallah.4 Others are not so convinced of the customs which lead up to the wedding that there is a concern and maintain one may and the wedding itself. marry at the end of the month as well.5 Some are only lenient if the chosson is twenty years of When one attends a wedding he sees many age.6 The custom of many is not to be customs which are done.1 For example, concerned about this and marry even at the walking down the aisle with candles, ashes on end of the month.7 Some say even according to the forehead, breaking the plate, and the glass, the stringent opinion one may marry until the the chosson does not have any knots on his twenty-second day of the Hebrew month.8 clothing etc. Long Engagement 4 Chazzon Yeshaya page 139, see Shar Yissochor mamer When an engaged couple decide when they ha’yarchim 2:pages 1-2. 5 Refer to Pischei Teshuva E.H. 64:5, Yehuda Yaleh 2:24, should marry, the wedding date should not be Tirosh V’yitzor 111, Hisoreros Teshuva 1:159, Teshuva 2 too long after their engagement. -

ESTUDIOS DEL TANAJ 54 Falsos Mesías Judíos

ESTUDIOS DEL TANAJ 54 Falsos Mesías Judíos Por: Eliyahu BaYona Director Shalom Haverim Org New York Estudios del Tanaj – Estudios del Tanaj 54 Yeshayahu 9 • 1. El pueblo que andaba en tinieblas, vio una luz grande. Sobre los que habitan en la tierra de sombras de muerte resplandeció una brillante luz. • 2. Multiplicaste la alegría, has hecho grande el júbilo, y se gozan ante ti, como se gozan los que recogen la mies, como se alegran los que reparten la presa. • 3. Rompiste el yugo que pesaba sobre ellos, el dogal que oprimía su cuello, la vara del exactor como en el día de Madián, • 4. y han sido echados al fuego y devorados por las llamas las botas jactanciosas del guerrero y el manto manchado en sangre. • 5 Pues nos ha nacido un hijo, un hijo que nos ha sido dado, y la autoridad está sobre su hombro, y el maravilloso consejero, el poderoso Dios, el Padre eterno, llamó su nombre, "el príncipe de la paz". • 6 En señal de abundante autoridad y de paz sin límite sobre el trono y el reino de David, para que se establezca firmemente en justicia y en equidad ahora y siempre. El celo del Señor de los ejércitos hará que esto suceda.. Estudios del Tanaj 54 Yeshayahu 9 • 6 En señal de abundante autoridad y de paz sin límite sobre el trono y el reino de David, para que se establezca firmemente en justicia y en equidad ahora y siempre. El celo del Señor de los ejércitos hará que esto suceda.. • Lemarbé hamisrá uleshalom en kes al kisé David ve’al mamlakto lehakin otá ulesa’ada bemishpat ubitzdaká me’atá ve’ad olam kinat Adonai tzevaot ta’aseh zot. -

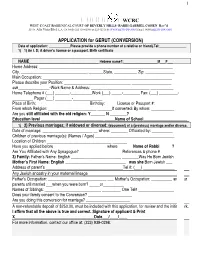

WCRC APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION)

1 WCRC WEST COAST RABBINICAL COURT OF BEVERLY HILLS- RABBI GABRIEL COHEN Rav”d 331 N. Alta Vista Blvd . L.A. CA 90036 323 939-0298 Fax 323 933 3686 WWW.BETH-DIN.ORG Email: INFO@ BETH-DIN.ORG APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION) Date of application: ____________Please provide a phone number of a relative or friend).Tel:_______________ 1) 1) An I. D; A driver’s license or a passport. Birth certificate NAME_______________________ ____________ Hebrew name?:___________________M___F___ Home Address: ________________________________________________________________ City, ________________________________ _______State, ___________ Zip: ______________ Main Occupation: ______________________________________________________________ Please describe your Position: ________________________________ ___________________ ss#_______________-Work Name & Address: ____________________________ ___________ Home Telephone # (___) _______-__________Work (___) _____-________ Fax: (___) _________- __________ Pager (___) ________-______________ Place of Birth: ______________________ ___Birthday:______License or Passport #: ________ From which Religion: _______________________ _______If converted: By whom: ___________ Are you still affiliated with the old religion: Y_______ N ________? Education level ______________________________ _____Name of School_____________________ 1) 2) Previous marriages; if widowed or divorced: (document) of a (previous) marriage and/or divorce. Date of marriage: ________________________ __ where: ________ Officiated by: __________ Children -

TORAH Weeklyparshat Beshalach 13 - 19 January, 2019 the Torah Finds It Necessary to Too Would Make Their Own 7 - 13 Shevat, 5779 the BONES of Mention Explicitly

בס״ד TORAH WEEKLYParshat Beshalach 13 - 19 January, 2019 the Torah finds it necessary to too would make their own 7 - 13 Shevat, 5779 THE BONES OF mention explicitly. Why? transition successfully. JOSEPH The answer is that Ever since leaving Torah : They say adapt or die. Joseph was unique. While Egypt, we’ve been wandering. Exodus 13:17 - 17:16 But must we jettison the old his brothers were simple And every move has brou- to embrace the new? Is the shepherds tending to their ght with it its own challen- Haftorah: choice limited to modern or flocks, Joseph was running ges. Whether from Poland the affairs of state of the mi- to America or Lithuania to Judges 4:4 - 5:31 antiquated, or can one be a contemporary traditionalist? ghtiest superpower of the day. South Africa, every transition Do the past and present ever To be a practicing Jew while has come with culture shocks CALENDARS co-exist? blissfully strolling through to our spiritual psyche. How We have Jewish At the beginning the meadows is not that com- do you make a living and still plicated. Alone in the fields, keep the Shabbat you kept in Calendars, if you would of this week’s Parshah we communing with nature, and the shtetl when the factory like one, please send us read that Moses himself was occupied with a special away from the hustle and bu- boss says “Cohen, if you don’t a letter and we will send mission as the Jews were stle of city life, one can more come in on Saturday, don’t you one, or ask the Rab- leaving Egypt. -

Pessi and Dovie Levy ט‘ אלול ה‘תשפ“א the 17Th of August, 2021 © 2021

לזכות החתן הרה"ת שלום דובער Memento from the Wedding of והכלה מרת פעסיל ליווי Pessi and Dovie ולזכות הוריהם Levy מנחם מענדל וחנה ליווי ט‘ אלול ה‘תשפ“א הרב שלמה זלמן הלוי וחנה זיסלא The 17th of August, 2021 פישער שיחיו לאורך ימים ושנים טובות Bronstein cover 02.indd 1 8/3/2021 11:27:29 AM בס”ד Memento from the Wedding of שלום דובער ופעסיל שיחיו ליווי Pessi and Dovie Levy ט‘ אלול ה‘תשפ“א The 17th of August, 2021 © 2021 All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof, in any form, without prior permission, in writing. Many of the photos in this book are courtesy and the copyright of Lubavitch Archives. www.LubavitchArchives.com [email protected] Design by Hasidic Archives Studios www.HasidicArchives.com [email protected] Printed in the United States Contents Greetings 4 Soldiering On 8 Clever Kindness 70 From Paris to New York 82 Global Guidance 88 Family Answers 101 Greetings ,שיחיו Dear Family and Friends As per tradition at all momentous events, we begin by thanking G-d for granting us life, sustain- ing us, and enabling us to be here together. We are thrilled that you are able to share in our simcha, the marriage of Dovie and Pessi. Indeed, Jewish law high- lights the role of the community in bringing joy to the chosson and kallah. In honor of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin’s wedding in 1928, the Frierdiker Rebbe distributed a special teshurah, a memento, to all the celebrants: a facsimile of a letter written by the Alter Rebbe. -

The Rosh Chodesh Planner Was Designed to Serve As a Resource for Shluchos When Planning Women's Programs. Many Years Ago, When

בס"ד PREFACE The Rosh Chodesh Planner was designed to serve as a resource for shluchos when planning women’s programs. Many years ago, when one of the first shluchim arrived in Pittsburgh, PA, prepared to combat the assimilation of America through hafotzas hamayonos, one of the directives of the Rebbe to the shlucha was that it did not suffice for her to only become involved in her husband’s endeavors, but that she should become involved in her own areas of activities as well. Throughout the years of his nesiyus, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Nesi Dorenu, appreciated and valued the influential role the woman plays as the akeres habayis. This is evident in the many sichos which the Rebbe dedicated specifically to Jewish women and girls worldwide. Involved women are catalysts for involved families and involved communities. Shluchos, therefore, have always dedicated themselves towards reaching a broad spectrum of Jewish women from many affiliations, professions and interests. Programs become educational vehicles, provide networking and outreach opportunities for the participants, and draw them closer in their unified quest for a better and more meaningful tomorrow. Many shluchos have incorporated a schedule of gathering on a monthly basis. Brochures are mailed out at the onset of the year containing the year’s schedule at a glance. Any major event(s) are incorporated as well. This system offers the community an organized and well-planned view of the year’s events. It lets them know what to expect and gives them the ability to plan ahead. In the z’chus of all the positive accomplishments that have been and are continuously generated from women’s programs, may we be worthy of the immediate and complete Geulah. -

Yeshivah College 2019 School Performance Report

בס”ד YESHIVAH COLLEGE 2019 SCHOOL PERFORMANCE REPORT Yeshivah College Educating for Life Yeshivah College Educating for Life PERFORMANCE INFORMATION REPORT 2019 This document is designed to report to the public key aspects identified by the State and Commonwealth Governments as linked to the performance of Schools in Australia. Yeshivah College remains committed to the continual review and improvement of all its practices, policies and processes. We are suitably proud of the achievements of our students, and the efforts of our staff to strive for excellence in teaching and outcomes. ‘Please note: Any data referencing Yeshivah – Beth Rivkah Colleges (or YBR) is data combined with our partner school, Beth Rivkah Ladies College. All other data relates specifically toY eshivah. Vision Broadening their minds and life experiences, Yeshivah - Beth Rivkah students are well prepared for a life of accomplishment, contribution and personal fulfilment. Our Values Jewish values and community responsibility are amongst the core values that distinguish Yeshivah - Beth Rivkah students. At Yeshivah - Beth Rivkah Colleges we nurture and promote: Engaging young minds, adventurous learning, strong Jewish identity, academic excellence and community responsibility. Our Mission We are committed to supporting the individual achievement and personal growth of each of our students. Delivering excellence in Jewish and General studies, a rich and nurturing environment and a welcoming community, our students develop a deep appreciation of Yiddishkeit (their Jewish identity) andT orah study. 1. PROFESSIONAL ENGAGEMENT STAFF ATTENDANCE In 2019, Yeshivah – Beth Rivkah Colleges (YBR) have been privileged to have a staff committed to the development of all aspects of school life. Teaching methods were thorough, innovative and motivating, and there was involvement in improving behavioural outcomes, curricula, professional standards and maintaining the duty of care of which the school is proud. -

SHABBAT MEVARCHIM Av 25, 5780 / August 14 - 15, 2020 Parsha/Haftorah: Artscroll: 998/1199; Hertz: 799/818; Living Torah: 924/1233 Pirkei Avot: Chapter 5

19-10 Morlot Avenue Andrew Markowitz, Rabbi Fair Lawn, NJ 07410 Benjamin Yudin, Rabbi Emeritus 201.791.7910/shomrei-torah.org T HE WEEKLY BRIEF: PARSHAT RE’EH – SHABBAT MEVARCHIM Av 25, 5780 / August 14 - 15, 2020 Parsha/Haftorah: Artscroll: 998/1199; Hertz: 799/818; Living Torah: 924/1233 Pirkei Avot: Chapter 5 SHABBAT ZEMANIM MAZAL TOV Friday, August 14, 2020 ❖ Pearl and Milty Frank on the marriage of their granddaughter Nicole Feigenblum to Avi Schneider. Early Mincha 6:15 pm (ST & DN) Mazal Tov also to their parents Cindy and David Feigenblum and Silvie and David Schneider Earliest Candle Lighting 6:34 pm ❖ Ceil and Sam Heller on the engagement of their son, Avi to Lauren Marcus of San Diego. Candle Lighting 7:37 pm Mincha/Kabbalat Shabbat 7:41 pm (STI) Shabbat, August 15, 2020 ❖ Susie and Robert Katz on the upcoming marriage of Robert’s son Joseph, to Rachel Fellus, daughter of Odette and James Fellus, of Dix Hills, Long Island. Due to COVID restrictions the family deeply regrets Earliest Tallit 4:59 am not being able to invite friends in the community. A live stream is available on Monday, August 17th, for Sunrise 6:06 am Shacharit those who would like to participate. The live stream will begin at 5:15 PM. Badeken will be around 5:40 7:20 (ST), 8:00 (DN), 8:15 (YB), 9:00 am (STI, ST & PM and Chuppah at 6:00 PM. Live stream link DNI) is https://livestream.com/accounts/17077440/events/9247404 Sof Z’man Kriat Sh’ma 9:31 am ❖ All the Daf Yomi Learning Participants and their families for their completion of Masechet Shabbat. -

Mr. Manchester

First Edition 2003 Second Edition 2004 40 years of Correspondence from the Lubavitcher Rebbe to Mr. & Mrs. Zalmon Jaffe Published and Copyright © 2003 by Rabbi Avrohom Jaffe 26 Old Hall Rd. Salford, Manchester M7 4JH England Fax: 44-161-795-7759 All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof, in any form, without prior permission, in writing, from the publisher, except for brief quotes in reviews and newspaper articles Printed in China Table of Contents Publisher’s Foreword XI Editor’s Introduction XIII 5712 7 Elul Rabbi Rein’s visit 1 5713 28 Shevat Maaser to Tzedokah 4 20 Iyar Increase in Torah study 6 5714 25 Adar II Blessing for business. Upcoming Bar Mitzvah 8 26 Nissan Blessing for son’s Bar Mitzvah 9 11 Menachem Av Business worries. ‘Wheel’ of fortune 10 5715 2 Tammuz Tzedokah. Communal position. Mikva 12 28 Menachem Av Preparations for 13 Tammuz. Changing gashmius to ruchnius 14 5716 16 Shevat, 5716 Strong faith. Tzedokah – more than maaser. Age for a Shiduch 15 5717 18 Kislev 19 Kislev wishes 16 13 Teves 19 Kislev celebrations. Mikva 17 12 Sivan Testing G-d. Business worries 19 15 Menachem Av Blessing 21 5718 5 Tishrei Re. son: One year of Torah study 22 14 Sivan Condolences 23 15 Sivan Speedy recovery 24 26 Tammuz Blessing for a successful court case 25 9 Elul G-d is my light and salvation 27 5719 7 MarCheshvon Exoneration from trial. Blessing 28 15 MarCheshvon Secretariat: arrangements for New York visit 29 Rosh Chodesh Kislev Successful surgery of wife 30 18 Adar I Follow-up of personal meeting 31 18 Adar I Secretariat: Follow up to visit 32 21 Adar II Blessing for wife’s treatment 33 5 Nissan Recovery of Mr. -

Chabad Chodesh Marcheshvan 5771

בס“ד MarCheshvan 5771/2010 SPECIAL DAYS IN MARCHESHVAN Volume 21, Issue 8 In MarCheshvan, the first Beis HaMikdash was completed, but was not dedicated until Tishrei of the following year. MarCheshvan was ashamed, and so HaShem promised that the dedication of the Third Beis HaMikdash would be during MarCheshvan. (Yalkut Shimoni, Melachim I, 184) Zechariah HaNavi prophesied about the rebuilding of the Second Beis HaMikdash. Tishrei 30/October 8/Friday First Day Rosh Chodesh MarCheshvan MarCheshvan 1/October 9/Shabbos Day 2 Rosh Chodesh MarCheshvan father-in-law of the previous Lubavitcher Shlomoh HaMelech finished building the Rebbe, 5698[1937]. Beis HaMikdash, 2936 [Melachim I, 6:35] Cheshvan 3/October 11/Monday Cheshvan 2/October 10/Sunday Yartzeit of R. Yisroel of Rizhyn, 5611[1850]. The Rebbe RaShaB sent a Mashpiah and "...The day of the passing of the Rizhyner, seven Talmidim to start Yeshivah Toras Cheshvan 3, 5611, was very rainy. At three in Emes, in Chevron, 5672 [1911]. the afternoon in Lubavitchn, the Tzemach Tzedek called his servant to tear Kryiah for Yartzeit of R. Yosef Engel, Talmudist, 5679 him and told him to bring him his Tefilin. At [1918]. that time news by telegraph didn't exist. The Rebbitzen asked him what happened; he said Yartzeit of R. Avrohom, son of R. Yisroel the Rizhyner had passed away, and he Noach, grandson of the Tzemach Tzedek, LUCKY BRIDES - TZCHOK CHABAD OF HANCOCKI NPARK HONOR OF THE BIRTHDAY OF THE REBBE RASHAB The fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom ular afternoon he remained in that position for DovBer, used to make frequent trips abroad a much longer time than usual. -

Rabbi Abrahams Receives Kos Shel Brocha From

RABBI ABRAHAMS RECEIVES KOS SHEL BROCHA FROM THE REBBE, LEVI FREIDIN VIA JEM 270100 MOTZEI SIMCHAS TORAH 5746*. TAMMUZ 5779 *z 40 A CHASSIDISHER DERHER 5746-1985 לחיזוק ההתקשרות לכ״ק אדמו״ר זי״ע נדפס ע״י החבר הצעיר בשליחות המל״ח קיץ ה'תשי״ט “ Wherever You Will Be... The Rebbe Will Be With You” Exclusive interview with Rabbi Yosef Abrahams Mashpia, Yeshivah Gedola Lubavitch of Greater Miami Rabbi Yosef Yeshaya Abrahams is the senior mashpia of Yeshivas Lubavitch of Miami. He merited to spend his years as a bochur in the Rebbe’s presence, during the years of kabbalas hanesius and after. We thank him for sharing his story. We also thank Rabbi Bentche Korf, mashgiach in the yeshiva, for conducting the interview on our behalf. TAMMUZ 5779 A CHASSIDISHER DERHER 41 My First Connections When I was eleven-years-old, my to the Frierdiker Rebbe for Rosh I was born in Philadelphia in 5697* family moved to Chicago, and we were Hashanah 5710*. members of the Chabad Bnei Reuven .(תרצ“ז) Shul, which still exists today. Only Seeing The My family wasn’t associated with Frierdiker Rebbe Lubavitch. The first time I encountered one month after our arrival, my father I began learning in Tomchei Chabad was as a seven-year-old tragically passed away, and towards Temimim, and naturally I participated student in Yeshivas Achei Temimim. the end of the year, my mother in many of the events in 770. The school was run by a Chossid from returned to Philadelphia. In those days, the Frierdiker Rebbe Nevel named Rabbi Schneiderman, I was already twelve-years-old, made minimal public appearances. -

Life Gives Birth to Death and Death Gives Birth to Life Yom Kippur Yizkor 5772 (2011) R

Life Gives Birth to Death and Death Gives Birth to Life Yom Kippur Yizkor 5772 (2011) R. Yonatan Cohen, Congregation Beth Israel I remember that in Yeshiva, my Rebbe was once asked how his Rosh Hashanah was. He said, “I don’t know. Ask me next year!” Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are days of difficult personal accounting. Our rabbis referred to this as cheshbon ha’nefesh, the internal calculations and considerations of the soul. On Yom Kippur in particular, death weighs heavily on the bottom line. We remove our shoes as though we are in a state of mourning. We wear white recalling the white shrouds enveloping the deceased. The Yizkor service reminds us of the fragility of life, while the daunting words and melody of Unetane Tokef pound upon us. Who shall live and who shall die… The totality of our life seems to stream in one single direction and death is seemingly so stubborn. In this room, right now, many of us are struggling with questions pertaining to the ultimate meaning of life especially in light of its finitude. We are struggling to locate the endurance of our spiritual legacy. We wonder how and if our children or those whose lives we touched will continue to perpetrate our way of life, our vision, our mission. We struggle physically as well. Some of us are ill, some of us are not yet ill, we all know people who are sick. We struggle with health, with the shortness of life, with its fragility. 1 Through it all, we struggle with finitude – with the perceived limits of our narrative, our inability to foresee the future, to let go or to invest, to pull away or draw closer in.