Pessi and Dovie Levy ט‘ אלול ה‘תשפ“א the 17Th of August, 2021 © 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TORAH Weeklyparshat Beshalach 13 - 19 January, 2019 the Torah Finds It Necessary to Too Would Make Their Own 7 - 13 Shevat, 5779 the BONES of Mention Explicitly

בס״ד TORAH WEEKLYParshat Beshalach 13 - 19 January, 2019 the Torah finds it necessary to too would make their own 7 - 13 Shevat, 5779 THE BONES OF mention explicitly. Why? transition successfully. JOSEPH The answer is that Ever since leaving Torah : They say adapt or die. Joseph was unique. While Egypt, we’ve been wandering. Exodus 13:17 - 17:16 But must we jettison the old his brothers were simple And every move has brou- to embrace the new? Is the shepherds tending to their ght with it its own challen- Haftorah: choice limited to modern or flocks, Joseph was running ges. Whether from Poland the affairs of state of the mi- to America or Lithuania to Judges 4:4 - 5:31 antiquated, or can one be a contemporary traditionalist? ghtiest superpower of the day. South Africa, every transition Do the past and present ever To be a practicing Jew while has come with culture shocks CALENDARS co-exist? blissfully strolling through to our spiritual psyche. How We have Jewish At the beginning the meadows is not that com- do you make a living and still plicated. Alone in the fields, keep the Shabbat you kept in Calendars, if you would of this week’s Parshah we communing with nature, and the shtetl when the factory like one, please send us read that Moses himself was occupied with a special away from the hustle and bu- boss says “Cohen, if you don’t a letter and we will send mission as the Jews were stle of city life, one can more come in on Saturday, don’t you one, or ask the Rab- leaving Egypt. -

Menachem Mendel Schneersohn

The Book of Chabad-Lubavitch Customs / 71 Nissan, 5680, in Rostov [on the River Don], and his resting place is there."285 "At about twenty minutes after four, with the approach of dawn on the second day of the first month, the highest heavens opened up, and the pure soul ascended — to pour itself forth into its Father's bosom. With a holy sweetness, with a noble tranquillity, our holy master handed over his soul to G-d, the L-rd of all spirits."286 (c) Yud-Alef Nissan: The eleventh of Nissan is the birthday of the seventh of the Rebbeim of Chabad, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson — ;תרס׳׳ב) the Lubavitcher Rebbe Shlita, who was born in 5662 ;תש׳׳י) and assumed the mantle of leadership in 5710 ,(1902 287.(1950 May he be blessed with long and happy years! (d) Yud-Gimmel Nissan: The thirteenth of Nissan is the yahrzeit of the third of the Rebbeim of Chabad, Rabbi Menachem Mendel — the Tzemach and] assumed the (תקמ׳׳ט; Tzedek, who [was born in 5549 (1789 תקפ׳׳ח; leadership in 5588 (288.(1827 "Moreover, we must inform you of the passing of our holy master during the night preceding Thursday, the thirteenth of Nissan, 37 minutes after ...289 a.m."290 his resting place is in the ;(תרכ׳׳ו; This was in 5626 (1866 village of Lubavitch. 285. From Chanoch LaNaar (Kehot, N.Y.), p. 16; see also HaYom Yom, entry for 2 Nissan. Regarding the circumstances of his passing, see Ashkavta DeRebbe [by Rabbi Moshe DovBer Rivkin; Vaad LeHadpasas HaKuntreis, N.Y., 1953]. -

The Rosh Chodesh Planner Was Designed to Serve As a Resource for Shluchos When Planning Women's Programs. Many Years Ago, When

בס"ד PREFACE The Rosh Chodesh Planner was designed to serve as a resource for shluchos when planning women’s programs. Many years ago, when one of the first shluchim arrived in Pittsburgh, PA, prepared to combat the assimilation of America through hafotzas hamayonos, one of the directives of the Rebbe to the shlucha was that it did not suffice for her to only become involved in her husband’s endeavors, but that she should become involved in her own areas of activities as well. Throughout the years of his nesiyus, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Nesi Dorenu, appreciated and valued the influential role the woman plays as the akeres habayis. This is evident in the many sichos which the Rebbe dedicated specifically to Jewish women and girls worldwide. Involved women are catalysts for involved families and involved communities. Shluchos, therefore, have always dedicated themselves towards reaching a broad spectrum of Jewish women from many affiliations, professions and interests. Programs become educational vehicles, provide networking and outreach opportunities for the participants, and draw them closer in their unified quest for a better and more meaningful tomorrow. Many shluchos have incorporated a schedule of gathering on a monthly basis. Brochures are mailed out at the onset of the year containing the year’s schedule at a glance. Any major event(s) are incorporated as well. This system offers the community an organized and well-planned view of the year’s events. It lets them know what to expect and gives them the ability to plan ahead. In the z’chus of all the positive accomplishments that have been and are continuously generated from women’s programs, may we be worthy of the immediate and complete Geulah. -

Yeshivah College 2019 School Performance Report

בס”ד YESHIVAH COLLEGE 2019 SCHOOL PERFORMANCE REPORT Yeshivah College Educating for Life Yeshivah College Educating for Life PERFORMANCE INFORMATION REPORT 2019 This document is designed to report to the public key aspects identified by the State and Commonwealth Governments as linked to the performance of Schools in Australia. Yeshivah College remains committed to the continual review and improvement of all its practices, policies and processes. We are suitably proud of the achievements of our students, and the efforts of our staff to strive for excellence in teaching and outcomes. ‘Please note: Any data referencing Yeshivah – Beth Rivkah Colleges (or YBR) is data combined with our partner school, Beth Rivkah Ladies College. All other data relates specifically toY eshivah. Vision Broadening their minds and life experiences, Yeshivah - Beth Rivkah students are well prepared for a life of accomplishment, contribution and personal fulfilment. Our Values Jewish values and community responsibility are amongst the core values that distinguish Yeshivah - Beth Rivkah students. At Yeshivah - Beth Rivkah Colleges we nurture and promote: Engaging young minds, adventurous learning, strong Jewish identity, academic excellence and community responsibility. Our Mission We are committed to supporting the individual achievement and personal growth of each of our students. Delivering excellence in Jewish and General studies, a rich and nurturing environment and a welcoming community, our students develop a deep appreciation of Yiddishkeit (their Jewish identity) andT orah study. 1. PROFESSIONAL ENGAGEMENT STAFF ATTENDANCE In 2019, Yeshivah – Beth Rivkah Colleges (YBR) have been privileged to have a staff committed to the development of all aspects of school life. Teaching methods were thorough, innovative and motivating, and there was involvement in improving behavioural outcomes, curricula, professional standards and maintaining the duty of care of which the school is proud. -

Mr. Manchester

First Edition 2003 Second Edition 2004 40 years of Correspondence from the Lubavitcher Rebbe to Mr. & Mrs. Zalmon Jaffe Published and Copyright © 2003 by Rabbi Avrohom Jaffe 26 Old Hall Rd. Salford, Manchester M7 4JH England Fax: 44-161-795-7759 All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof, in any form, without prior permission, in writing, from the publisher, except for brief quotes in reviews and newspaper articles Printed in China Table of Contents Publisher’s Foreword XI Editor’s Introduction XIII 5712 7 Elul Rabbi Rein’s visit 1 5713 28 Shevat Maaser to Tzedokah 4 20 Iyar Increase in Torah study 6 5714 25 Adar II Blessing for business. Upcoming Bar Mitzvah 8 26 Nissan Blessing for son’s Bar Mitzvah 9 11 Menachem Av Business worries. ‘Wheel’ of fortune 10 5715 2 Tammuz Tzedokah. Communal position. Mikva 12 28 Menachem Av Preparations for 13 Tammuz. Changing gashmius to ruchnius 14 5716 16 Shevat, 5716 Strong faith. Tzedokah – more than maaser. Age for a Shiduch 15 5717 18 Kislev 19 Kislev wishes 16 13 Teves 19 Kislev celebrations. Mikva 17 12 Sivan Testing G-d. Business worries 19 15 Menachem Av Blessing 21 5718 5 Tishrei Re. son: One year of Torah study 22 14 Sivan Condolences 23 15 Sivan Speedy recovery 24 26 Tammuz Blessing for a successful court case 25 9 Elul G-d is my light and salvation 27 5719 7 MarCheshvon Exoneration from trial. Blessing 28 15 MarCheshvon Secretariat: arrangements for New York visit 29 Rosh Chodesh Kislev Successful surgery of wife 30 18 Adar I Follow-up of personal meeting 31 18 Adar I Secretariat: Follow up to visit 32 21 Adar II Blessing for wife’s treatment 33 5 Nissan Recovery of Mr. -

Weekly Sponsors

Weekly Sponsors Chayenu depends on–and is made possible through–the generous contributions of individuals & families, whose continued support facilitates the worldwide daily Torah-study through Chayenu. Weekly sponsors feature prominently on the back cover page, during the week of their particular dedication, and are listed here for one full year, thereafter. To join our growing family of supporters/partners and have the merit of thousands of Jews' Torah-study for an entire week (or for other sponsorship opportunities) visit www.chayenu.org/dedicate Note: Many of these dedications are continued from last year, and will become available this coming year. Please check with us, if you are interested in a particular week. לעילוי נשמת האשה החשובה רוחמה חי׳ פרומא ע”ה בת – יבדלח"ט – ר’ דוב פנחס שי‘ ולזכות משפחתה לאריכות ימים ושנים טובות מרדכי, אפרים, עדינה, משה, נעמי, אהרון, יהודה לייב ביסטריצקי בראשית In loving memory of Ruchama Chaya Fruma Bas R’ Dov Pinchas In honor of her loving family for long and healthy years Morty (Marcus), Ephraim, Adina, Moshe, Naomi, Aharon, Yehuda Leib Bistritzky In Loving Memory Of Our Parents לעילוי נשמות הרב החסיד והתמים אסתר בת ר‘ יוחנן ע“ה גאלדמאן ר‘ שמעון ע“ה נפטרה י”ז תשרי בן ר‘ שמואל זאנוויל הי“ד Esther Goldman A“H גאלדמאן Her open home, open heart, and unique blend of wit and wisdom נפטר כ“ט תשרי impacted all who met her. נח R’ Shimon ר‘ יצחק יעקב בן ר‘ משה ע“ה סיימאן Goldman A“H נפטר ד‘ אדר א‘ R’ Yitzchok Yaakov (Jerry) His family’s sole survivor of the Simon A“H Holocaust who overcame the odds His joy was infectious, his food and raised a family of Chassidim. -

HASSIDISM in FRANCE TODAY: a PECULIAR CASE? Jacques Gutwirth

HASSIDISM IN FRANCE TODAY: A PECULIAR CASE? Jacques Gutwirth HIs paper attempts to describe Hassidism in France today within its historical and sociological context. That country's hassidic T movement is in fact limited to only one group: the Lubavitch, who have displayed a remarkable and astonishing dynamism in the heart of a population which has not in the past been drawn to any form of Hassidism. 1 France has certainly not been a country of choice for the hassidim- neither before nor immediately after the Second World War. Surprisingly, it was only after 1960 (with the mass emigration of North Mrican Jews) that only one hassidic movement, that of the Lubavitch, took hold in France among the newcomers and soon spread throughout the country. That was a doubly peculiar development with the domina tion of only one hassidic movement among a section ofJewry which had rarely been attracted to that type ofJudaism. Nowadays in France there are believed to be some 10,ooo to 15,000 Lubavitch followers (men, women, and children). A proportion of these are loyal adherents while the rest are 'sympathisers' who attend more or less regularly the movement's synagogues or prayer houses. Although 10,ooo to 15,000 represent only two to three per cent of the half-million French Jews( we must bear in mind that before 1950 the country had barely a few dozen Hassidic families of mainly Russian or Ukrainian origin. Nowadays, however, at least three-quarters of the Lubavitch members or sympathisers are of North Mrican origin (from Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria) and are mostly the children and grandchildren - the so-called second and third generations - of those who immigrated in the 1g6os. -

Chabad Chodesh Marcheshvan 5771

בס“ד MarCheshvan 5771/2010 SPECIAL DAYS IN MARCHESHVAN Volume 21, Issue 8 In MarCheshvan, the first Beis HaMikdash was completed, but was not dedicated until Tishrei of the following year. MarCheshvan was ashamed, and so HaShem promised that the dedication of the Third Beis HaMikdash would be during MarCheshvan. (Yalkut Shimoni, Melachim I, 184) Zechariah HaNavi prophesied about the rebuilding of the Second Beis HaMikdash. Tishrei 30/October 8/Friday First Day Rosh Chodesh MarCheshvan MarCheshvan 1/October 9/Shabbos Day 2 Rosh Chodesh MarCheshvan father-in-law of the previous Lubavitcher Shlomoh HaMelech finished building the Rebbe, 5698[1937]. Beis HaMikdash, 2936 [Melachim I, 6:35] Cheshvan 3/October 11/Monday Cheshvan 2/October 10/Sunday Yartzeit of R. Yisroel of Rizhyn, 5611[1850]. The Rebbe RaShaB sent a Mashpiah and "...The day of the passing of the Rizhyner, seven Talmidim to start Yeshivah Toras Cheshvan 3, 5611, was very rainy. At three in Emes, in Chevron, 5672 [1911]. the afternoon in Lubavitchn, the Tzemach Tzedek called his servant to tear Kryiah for Yartzeit of R. Yosef Engel, Talmudist, 5679 him and told him to bring him his Tefilin. At [1918]. that time news by telegraph didn't exist. The Rebbitzen asked him what happened; he said Yartzeit of R. Avrohom, son of R. Yisroel the Rizhyner had passed away, and he Noach, grandson of the Tzemach Tzedek, LUCKY BRIDES - TZCHOK CHABAD OF HANCOCKI NPARK HONOR OF THE BIRTHDAY OF THE REBBE RASHAB The fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom ular afternoon he remained in that position for DovBer, used to make frequent trips abroad a much longer time than usual. -

T S Form, 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

t s Form, 990-PF Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state report! 2006 For calendar year 2006, or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that a Initial return 0 Final return Amended return Name of identification Use the IRS foundation Employer number label. Otherwise , HE DENNIS BERMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 31-1684732 print Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite Telephone number or type . 5410 EDSON LANE 220 301-816-1555 See Specific City or town, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here l_l Instructions . state, ► OCKVILLE , MD 20852-3195 D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Foreign organizations meeting 2. the 85% test, ► H Check type of organization MX Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation = Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt chartable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method 0 Cash Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, col (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination $ 5 010 7 3 9 . (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) under section 507 (b)( 1 ► )( B ) , check here ► ad 1 Analysis of Revenue and Expenses ( a) Revenue and ( b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) may not for chartable purposes necessary equal the amounts in column (a)) expenses per books income income (cash basis only) 1 Contributions , gifts, grants , etc , received 850,000 . -

Torah Online - Rabbi Tuvia Bolton

Torah Online - Rabbi Tuvia Bolton In this week's section tells of how a talented rabble-rouser called Korach succeeded in inciting the entire Jewish nation against Moses declaring; "Why do you (Moses) raise yourself over the congregation of G-d!" (16:3) At first glance, this was a pretty stupid complaint. Moses was the one who single-handedly led the Jews from Egypt, went up on Mt. Sinai to get the Torah, constantly received orders from G-d, brought Manna from heaven and water from a rock to feed all the Jews. It was obvious that he deserved to be the head! Not only that, but Korach himself wanted to rule! So his complaint was transparent as well. Why did it inflame everyone? To understand this here are two stories. Michael Sofer and his wife Atara were avowed atheists. Born and bred in the Israeli commune system (Kibbutzim) they were devoted heart and soul to the ultra communist "Shomair HaTzair" (the 'Young Guard') ideal; hating anything that reeked of religion…. especially the Jewish religion. But all that changed. It began with the communist revolution and takeover of Czechoslovakia. At first the Sofers were overjoyed with the news; but when the new 'enlightened' regime in a rash of brutal arrests and imprisonments, incarcerated a 'Shomer HaTzair' friend of theirs who worked there called Mordechi Oren with the ridiculous charge of 'spying for the benefit of England' they began to realize that Communism was as evil and corrupt as everyone said it was. It wasn't long before they became disenchanted with the Kibbutz movement as well and eventually decided, as so many myriads of their Israeli brothers and sisters, to leave the country for greener pastures. -

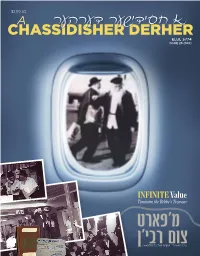

Elul 5774 ISSUE 23 (100)

$2.00 US ELUL 5774 ISSUE 23 (100) CHARTER TO THE REBBE – TISHREI 5721 בס“ד מ'פארט צום רבי'ן 2 | A CHASSIDISHER DERHER ולכתיבה וחתימה טובה לכל אחד ואחד שליט"א $2.00 US ELUL 5774 ISSUE 23 (100) CHARTER TO THE REBBE – TISHREI 5721 AV 5774 | 3 PHOTO: JEM/THE LIVING ARCHIVE / 104489 Moifsim in Chabad? There is a fascinating story told by the Frierdiker Rebbe about Chai Elul, which the Rebbe recounted many times throughout the years: On Shabbos Chai Elul, 5652, the Rebbe Rashab ascended to Gan Eden (still during his lifetime) along with his father, the Rebbe Maharash, where he heard seven “Toros” from the Baal Shem Tov.1 In this sicha, the Rebbe expounds on the nature of this miraculous event, deriving an important lesson for each of us.2 Throughout the generations of Chabad, Firstly, the fact that the Rebbe Rashab nature. But in truth, all of nature is really there has never been an emphasis on heard Toros from the Baal Shem Tov in Gan miraculous, so there is no reason to make a “moifsim”—supernatural events. True, all of Eden is a moifes.—a heavenly revelation tumult out of a moifes. our Rabbeim did indeed perform miracles, from above. Then, by expounding upon the The answer: and more so in recent times; nevertheless, Toros in his own words, the Rebbe Rashab Firstly, when he is in desperate need of these occurrences were not publicized translated this revelation into human help in his own material matters, he begs as in the times of the Baal Shem Tov. -

Chabad Chodesh Menachem Av 5780 Av Menachem Chodesh Chabad CONGREGATION LEVI YI

בס“ד Menachem Av 5780/2020 SPECIAL DAYS IN MENACHEM AV Volume 31, Issue 5 Menachem Av 1/July 22/Wednesday Rosh Chodesh "When Av comes in, we minimize happiness" (Taanis 26B) "In the nine days from Rosh Chodesh Av on we should try to make Siyumim." (Likutei Sichos Vol. XIV: p. 147) Mountains emerged above the receding Flood waters (BeReishis 8:5, Rashi) Plague of frogs in Mitzrayim. (Seder HaDoros) Yartzeit of Aharon HaKohen, 2489 [1312 BCE], the only Yartzeit recorded in the Torah, (BaMidbar 33:38) (in Parshas Masaei, read every year on the Shabbos of the week of his Yartzeit) Ezra and his followers arrived in Yerushalayim, 3413 [457 BCE]. (Ezra 7:9) Menachem Av 2/July 23/Thursday Titus commenced battering operations In Av 5331 [430 BCE] there was a debate against the courtyard of the Beis between Chananya ben Azur and Yirmi- HaMikdash, 3829 [70]. yahu. Chananya prophesized that Nevu- chadnetzer and his armies would soon The Previous Lubavitcher Rebbe arrived in leave Eretz Yisroel, and all the stolen vessels Eretz Yisrael, on his historic visit, 5689 from the Beis Hamikdash would be re- [1929]. turned from Bavel along with all those who were exiled. Yirmiyahu explained, that he Menachem Av 4/July 25/Shabbos Chazon too wished that this would happen, but the Reb Hillel of Paritch would say in the prophesy is false. Only if the Jews do TZCHOK CHABAD OF HANCOCK PARK name of R. Levi Yitzchok of Berditchev: Teshuvah can the decree be changed. "Chazon" means vision; on Shabbos Cha- Yirmiyahu also said that in that year zon, HaShem shows every Jew a vision of Chananya will die, since he spoke falsely in the Third Beis Hamikdash".