Poems by Faiz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

230239875.Pdf

======================================================================== ======================================================================== Log Report - Stellar Phoenix NTFS Data Recovery v4.1 ======================================================================== ======================================================================== ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Recovering File ---------------------------------------------------------------- -------- - Process started - Started on: Apr 20 2014 , 11:33 AM - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Amanda.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160 gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Despertar.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160 gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Din Din Wo (Little Child).wma - [Recov ered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Distance.wma - [Recov ered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\I Guess You're Right.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\I Ka Barra (Your Wor k).wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Love Comes.w ma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Muita Bobeir a.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\OAM's Blues. wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\One Step Bey ond.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Symphony_No_ 3.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\desktop.ini - [Recovered] - Process completed - Completed on : Apr 20 2014 , 11:41 AM ------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

Pakistani Televisions' Content in 2020 Television Can Play A

JMCS | JOURNAL OF MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION STUDIES Volume 1, Issue 2. July 2021 Programs for Children: Pakistani Televisions’ Content in 2020 Nabila Tabassum1 Abstract Television can play a significant role in nation building and children are generally viewed to be playing a vital role in building the image of a nation. Due to its significance, recent years have seen a worldwide rise in the media content that focuses children as the target audience. Several studies had investigated Pakistani televisions’ content with reference to adults, women and youth audiences. Studies related to children had mostly focused on the impact of television content on children or children's attitudes towards television content. However, the impact of educating and entertaining television on Pakistani children has received limited attention. Therefore, this paper initiated to examine the role of Pakistani television channels to educate or entertain Pakistani children, during January-December 2020. The foremost objective of this paper is to examine the proportion of children's programs in the top four Pakistani entertainment television channels. For this reason, the transmissions of top five Pakistani general entertainment television channels were taken into account included; Hum TV HD, ARY Digital, Geo Entertainment, and ARY Zindagi. The study found only a few programs for children that were fulfilling the purposes of entertaining and educating. Hence, Pakistani television channels are not fulfilling their responsibility in nation-building, as being a social agent of change, the media is responsible to play a key role in building their character and improving the ethical standards of Pakistani children. Keywords: Children Programs, Entertainment, Nation Building, Pakistani Television, Social Responsibility. -

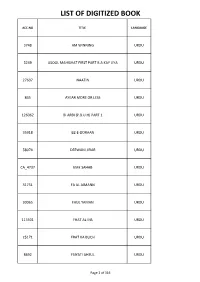

List of Digitized Book

LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK ACC.NO TITLE LANGUAGE 3748 AM WINNING URDU 5249 ASOOL MAHISHAT FIRST PART B.A KAY LIYA URDU 27607 NAATIN URDU 845 AYEAR MORE OR LESS URDU 126062 BI ARBI (P.B.U.H) PART 1 URDU 35918 BZ-E-DORAAN URDU 58074 DEEWANI JIRAR URDU CA_4737 EME SAHAB URDU 31751 FA AL AIMANN URDU 30065 FAUL YAMAN URDU 113501 FHAT AL INS URDU 25171 FRAT KA BUCH URDU 8692 FSIYATI AHSUL URDU Page 1 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 30138 FSIYAT-I-AFFA URDU 34069 FTAHUL YAMAN URDU 1907 FTAHUL YAMAN BATASHYAT URDU 24124 GAMA-I-TIBISHAZAD URDU 58190 GAMAT UL ASRAR URDU 3509 GD SAKHN URDU 64958 GMA SARMAD URDU 114806 GMAH JAVEED URDU 30328 GMAY ZAR URDU 180689 GSH FIRQAADI URDU 126188 HBZ HAYAT URDU 23817 I AUR PURANI TALEEM URDU 38514 IR G KHAYAL URDU 63302 JANGI AZADI ATHARA SO SATAWAN URDU Page 2 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 27796 KASH WA KASH URDU 24338 L DAMNIYATI URDU 57853 LAH TASLEEM URDU 5328 MEYATI KEMEYA KI DARSI KITAB URDU 36585 MOD-E-ZINDAGI URDU 113646 MU GAZAL FARSI URDU 1983 PAD MA SHEIKH FARIDIN ATTAR URDU ASL101 PARISIAN GRAMMER URDU 109279 QASH-I-AKHIR URDU 36043 QOOSH MAANI URDU 7085 QOOSHA RANGA RANG URDU 59166 QSH JAWOODAH URDU 38510 QSH WA NIGAAR URDU 23839 RA ZIKIR HUSSAIN(AS) URDU Page 3 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 456791 SAB ZELI RIYAZI URDU 5374 SEEBIYAT URDU 55986 SHRIYATI MAJID FIRST PART URDU 56652 SIRUL SHQEEN WA GAZLIYAT WA QASAYID URDU 47249 TAIEJ ALZAHAN WAFIZAN AL FIKAR URDU 11195 TAK KHATHA URDU ASL124 TIYA KALAM URDU 109468 VEEN BHARAT URDU CA_4731 WA-E-SHAIDA URDU ASL_286 YA HISAAB URDU 39350 ZAM HIYA HIYA URDU -

Rafiq-Ul-Mu'tamireen

ۡ E ۡ Raf iq-ul-Mu’tamireen ‘Umrah ka Tareeqa aur Du’aen Shaykh-e-Tareeqat, Ameer-e-Ahl-e-Sunnat, Bani-e- Dawat-e-Islami, Hazrat ‘Allamah Maulana Abu Bilal Muhammad Ilyas Attar َ َ ۡ َ َ َ ُ ُ ُ ۡ َ دا ا ِ َ Qadiri Razavi Maktaba-tul-Madinah Alami Madani Markaz, Faizan-e-Madinah Mahallah Saudagran, Purani Sabzi Mandi, Bab-ul-Madinah, Karachi, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] - [email protected] Phone: +92-21-34921389-93 – 34126999 Fax: +92-21-34125858 Fehrist Kitab Perhnay ki Du’a ..................................................................................... ii ‘Umray walay kay liye 52 Niyyaten .............................................................. iii Aap ko ‘Azm-e-Madinah mubarak ho ........................................................ xii Go Zaleel-o-Khuwar hun ker dou karam .................................................. xiv Raf iq-ul-Mu’tamirin .............................................................. 1 Durood-e-Pak ki Fazeelat ............................................................................... 1 ٖ Teen (3) Farameen-e-Mustafa 3 , ......................................... 1 ‘Umrah ki tayyari ki-jiye ................................................1 Ihraam bandhnay ka tareeqa .......................................................................... 1 Islami behnon ka Ihraam ................................................................................ 2 Ihraam kay nawafil ......................................................................................... -

DUA E NUDBA (PART 4) Bismillah, Ar-Rahman, Ar-Rahim

DUA E NUDBA (PART 4) Bismillah, ar-Rahman, ar-Rahim Azeem aur daimi rehmaton walay Allah kay naam se تُضاہ ٰی بِنَ ْف ِسی ٲَ ْن َت ِم ْن نَ ِصی ِف َش َر ٍف ﻻَ یُسا َو ٰی إلی َمتَی ٲَحا ُر فِی َک یَا َم ْوﻻ َی َو إ َلی tozaahaa be-nafsee anta min naseefe sharafin laa yosaawaa elaa mataa a-haaro feeka yaa mawlaaya wa elaa qurbaan aap jo Sharf rakhtay hain woh kisi aur ko nahi mil sakta kab tak hum aap ke liye be chain rahen ge ae mere aaqa aur kab tak َمتَ ٰی َوٲَ َّی ِخطا ٍب ٲَ ِص ُف فِی َک َوٲَ َّی نَ ْج َو ٰی َع ِزی ٌز َع َل َّی ٲَ ْن ٲُ َجا َب ُدونَ َک َوٲُنا َغ ٰی َع ِزی ٌز mataa wa ayya khetaabin asefo feeka wa ayya najwaa a'zeezun a'layya an ojaaba doonaka wa onaaghaa azeezun aur kistarah aap se khitaab karoon aur sargoshi karoon yeh mujh par giran hai ke siwaye apke kisi se jawab paon ya batein sunon mujh par َع َل َّی ٲَ ْن ٲَ ْب ِکیَ َک َویَ ْخذُلَ َک ا ْل َو َر ٰی َع ِزی ٌز َع َل َّی ٲَ ْن یَ ْج ِر َی َع َل ْی َک ُدونَ ُھ ْم َما َج َر ٰی َھ ْل a'layya an abkeyaka wa yakhzolakal waraa azeezun a'layya an yajreya a'layka doonahum maa jaraa hal giran hai ke mein aap ke liye roon aur log aapko chhorey rahen mujh par giran hai ke logon kitrf se aap par guzray jo guzray tou ُ ُ ِم ْن ُم ِعی ٍن َفٲ ِطی َل َمعَہُ ا ْلعَ ِوی َل َوا ْلبُکا َئ َھ ْل ِم ْن َج ُزوعٍ َفٲسا ِع َد َج َز َعہُ إذ َخﻻ َھ ْل َق ِذیَت min mo-e'enin fa-oteela ma-a'hul a'weela wal bokaaa-a hal min jazoo-i'n a-osaa- e'da jaza-a'hu ezaa khalaa hal qazeyat kya koi saathi hai jisske sath mil kar aap ke liye giryaa o zari karoon kya koi be- taab hai ke jab woh tanha ho to -

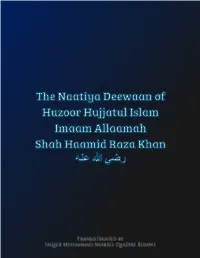

Transliterated by Faqeer Muhammad Shakeel Qaadiri Ridawi

Transliterated by Faqeer Muhammad Shakeel Qaadiri Ridawi Foreword All Praise is due to Almighty Allah, The Creator and Sustainer of the Universe. Peace, Blessings, and Salutations, upon Him whose excellence is above the entire creation and who has been blessed with being Imam ul Ambia. Peace and Blessings upon His Beloved Companions, who are the manifestation of His blessings, and upon His Noble Family who are the Gates to the City of His Love, and upon the Awliyah-e-Kiraam and Ulama-e-Izaam, especially upon His beloved and upon ,رضي هللا عنه descendant, the Imam ul Awliyah, Sayyiduna Shaykh Abdul Qaadir Jilani all those who follow in His way with sincerity. By the Grace of Allah, the Mercy of Sayyiduna Rasoolullah and the Karam of Ghauth-o-Khwaja- o-Raza, and my Masha’ikh especially Huzoor Sayyidi Taajush Shariah, Huzoor Sayyidi you have before you a ,(عليه الرحمة) Muhad’dith Kabeer and Huzoor Syed Shah Turabul Haq .رضي هللا عنه transliteration of the Naatiya kalaam of Hujjatul Islam Imam Haamid Rida Khan Huzoor Hujjatul Islam is the eldest son of Huzur Alahadrat Azeemul barakat Imam Ahmad Rida Hazrat Hujjatul Islam was an extremely pious mountain of knowledge, his .رضي هللا عنه Khan appearance was such that those who saw him were left in awe of his beauty. He attained his He .رضي هللا عنه knowledge at the feet of his blessed father, Sayyiduna A’la Hadrat Azeemul Barkat attained proficiency in the fields of Hadith, Islamic Jurisprudence, Tafseer etc. and graduated with distinctions at the tender age of nineteen. -

Hum Drama Karb Song Download

Hum drama karb song download LINK TO DOWNLOAD Watch the latest HUM TV drama serials, shows, events & LIVE stream on your android devices for free. HUM TV mobile app lets you watch your favorite shows using your Wi-Fi or cellular network anywhere, anytime. HUM TV mobile app also enables you to know more about your favorite drama serials from detailed information on Cast & Crew, Synopsis, Exclusive videos, OSTs, Promos, upcoming schedules /5(K). Listen online or download this beautiful song in the beautiful voice of Ali Zafar. Mushk OST is sung by Ali Zafar. Listen this song online or download in MP3 format from renuzap.podarokideal.ru Mushk OST is one of the best ost sung by Ali Zafar. Listen online or download the title song of HUM TV Drama serial “Mushk” in mp3 format from this site. Listen this song online or download in MP3 format from renuzap.podarokideal.ru Saraab OST is one of the best ost sung by Naveed Nashad. Listen online or download the title song of HUM TV Drama serial “Saraab” in mp3 format from this site. Download Saraab Drama Song in mp3. Saraab Full OST – New Drama serial Coming Soon only on HUM TV. Latest HUM TV Dramas Tera Ghum Aur Hum. Mohabbat Tujhe Alvida. HUM TV Dramas - Watch most popular and famous Pakistan # 1 TV channel for Urdu drama serials, videos & also watch HUM TV live. For those who have seen Sang e Mar Mar, the name of Mustafa Afridi is a good enough reason to watch Aangan. Listen and download all the latest Pakistani OST Drama Songs featured in serial, sitcoms etc. -

Of 13 a a Aab Aab-Aab

Page 1 of 13 A A Aab Aab-aab (a.) n.f.: water, lustre, sharpness. (p.) adv.: ashamed , blushed. Aab-daar Aab-deedah (adj.): polished, bartender,sharp. (p.) adj.: tearful, in tears. Aab-e-aatish Aab-e-deedah (p.) n.m.: wine, liquid fire. (p.) n.m.: tears, tearful eyes. Aab-e-hayaat Aab-e-rawaan (p.) n.m.: elixir, nectar. (p.) n.m.: running water, spring. Aab-e-zar Aabgeenah (p.) n.m.: liquid gold, ink of gold. (p.) n.m.: cup, tumbler, mirror. Aab-joo Aab-o-daanah (p.) n.f.: stream, rivulet. (p.) n.m.: subsistence, daily bread. Aab-o-gil Aab-o-hawaa (p.) n.f.: water and clay, elements of universe, (p.) n.f.: climate, water and air. nature. Aab-shaar Aab-yaaree (p.) n.f.: waterfall. (p.) n.m.: irrigation, watering. Aabaadee Aabid (p.) n.m.: population, habitation. (a.) n.m.: worshipper, devotee, adorer. Aabilah Aablah-paa (p.) n.m: blister, boil. (p.) n.m.: having blisters on the feet. Page 2 of 13 A A Aabroo Aab-rood (p.) n.f.: honour, dignity, chastity. (p.) n.f.: stream, rivulet. Aabroo-rezee Aadaab (p.) n.f.: slander, vilification, disgrace. (a.) n.m.pl.: salutation, etiquette. Aadee Aadil (a.) adj.: addicted, accustomed, habituated. (a.) n.: just, equitable. Aa’een Aa’eenah (p.) n.m.: code, custom, constitution. (p.) n.m.: a mirror, human heart. Aa’eenah-roo Aa’eenah-saaz (p.) adj.: fair faced, bright faced. (p.) n.m.: maker of mirrors, God, Creator. Aafaaq Aafaaqee (a.) n.pl.: horizons, the world. (a.) adj.: universal, global. -

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2017

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2017 Contents Exhibitions 2 Traveling Exhibitions 3 Film Series at the Dryden Theatre 4 Programs & Events 5 Online 7 Education 8 The L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation 8 Photographic Preservation & Collections Management 9 Photography Workshops 10 Loans 11 Objects Loaned For Exhibitions 11 Film Screenings 15 Acquisitions 17 Gifts to the Collections 17 Photography 17 Moving Image 29 Technology 35 George Eastman Legacy 37 Purchases for the Collections 39 Photography 39 Moving Image 39 Technology 39 George Eastman Legacy 39 Conservation & Preservation 40 Conservation 40 Photography 40 Technology 44 George Eastman Legacy 44 Richard and Ronay Menschel Library 44 Preservation 44 Moving Image 44 Financial 46 Treasurer’s Report 46 Fundraising 48 Members 48 Corporate Members 50 Matching Gift Companies 51 Annual Campaign 51 Designated Giving 52 Honor & Memorial Gifts 53 Planned Giving 54 Trustees, Advisors & Staff 55 Board of Trustees 55 George Eastman Museum Staff 56 George Eastman Museum, 900 East Avenue, Rochester, NY 14607 Exhibitions Exhibitions on view in the museum’s galleries during 2017. Catherine Opie: 700 Nimes Road Lucinda Devlin: Sightlines ONGOING Curated by Helen Molesworth, chief curator, the Curated by Lisa Hostetler, curator in charge, From the Camera Obscura to Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles), Department of Photography the Revolutionary Kodak organized for the George Eastman Museum Project Gallery Curated by Todd Gustavson, curator, by Jamie M. Allen, associate curator, -

February, 2021

E-Register: February, 2021 S. No. Diary No. RoC No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 362/2017-CO/A A-136165/2021 1/02/2021 LAURA B. Artistic KULBIR SINGH 2 20654/2020-CO/M M-685/2021 1/02/2021 RUDRASTHAKAM Music NAMITA RAY 3 19323/2020-CO/L L-99076/2021 1/02/2021 METER DOWN 79 PAGES Literary/ KINGSUK SARKHEL SCRIPT OF SCREEN PLAY Dramatic 4 17192/2020-CO/A A-136166/2021 1/02/2021 LE KACHUKO LE SHIV TIME Artistic THAKKAR JAYESHKUMAR PASS GOVINDBHAI - PIPLESHWAR SALES AGENCY PATAN. 5 14893/2020-CO/SW SW-14154/2021 1/02/2021 AROGYA ASHA Computer KUSHAGRA MAHANSARIA ,OM Software PRAKASH MAHANSARIA 6 20689/2020-CO/L L-99043/2021 1/02/2021 Symbol of Gurushakthi Literary/ Avatar Shreesathyam Dramatic 7 16537/2020-CO/A A-136167/2021 1/02/2021 MPRG Artistic MPRG LLP 8 16664/2020-CO/SW SW-14155/2021 1/02/2021 OPTIMIZATION ASSISTED Computer AMITKUMAR SUBHASHRAO RESOURCE ALLOCATION Software MANEKAR ,Dr. PRADEEPINI GERA WITH MULTI-CONSTRAINTS IN BDA 9 16713/2020-CO/L L-99047/2021 1/02/2021 Internet of things Enabled Literary/ Smita R. Kapse Soil Testing & NPK Nutrient Dramatic Detection 10 16922/2020-CO/L L-99056/2021 1/02/2021 PARAMPARAON KA Literary/ ND eRetail Distributor And Traders GULDASTA Dramatic 11 21018/2020-CO/L L-99055/2021 1/02/2021 Take Them Back Literary/ Rasleen Kour Dramatic 12 21252/2020-CO/L L-99062/2021 1/02/2021 BK SONG 1 CHAPTER I Literary/ BHARAT KEDIA Dramatic 13 21244/2020-CO/A A-136171/2021 1/02/2021 Pattern Artistic Lovely Professional University 14 17752/2020-CO/L L-99058/2021 1/02/2021 Fragrance of Life: Literary/ Mr. -

Song Listing Station Listing Lata Mangeshkar

SONG LISTING STATION LISTING LATA MANGESHKAR 01. Chupchup Khade Ho Zaroor Koi Baat Hai 37. Dekh Liya Maine Kismat Ka Tamasha 71. Chandan Ka Palna Resham Ko Dori Film: Badi Bahen Film: Deedar Film: Shabab Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar, Premlata Artistes: Mohammed Rafi, Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar,Hemant Kumar Lata Mangeshkar 02. Chhod Gaye Balam Mujhe 72. Dekho Woh Chand Chhupke Film: Barsaat 38. Hamein Ho Gaya Tumse Pyar Film: Shart Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar, Mukesh Film: Madhosh Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar, Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Hemant Kumar 03. Hawa Mein Udta Jaye Film: Barsaat 39. Thandi Hawayein 73. Gaya Andhera Hua Ujala Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Film: Naujawan Film: Subah Ka Tara Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar, 04. Barsaat Mein Humse Mile Talat Mahmood Film: Barsaat 40. Aaja Aaja Tera Intezar Hai Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Film: Sazaa 74. Jeevan Ke Safar Mein Rahi Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar, Film: Munimji 05. Jiya Beqarar Hai Talat Mahmood Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Film: Barsaat Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar 41. Mohe Bhool Gaye Sanwariya 75. Suno Chhoti Si Gudiya Ki Kahani Film: Baiju Bawra (Happy) 06. Patli Kamar Hai Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Film: Seema Film: Barsaat Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar, Mukesh 42. Tu Ganga Ki Mauj Film: Baiju Bawra 76. Man Mohana Bade Jhoothe 07. Meri Ankhon Mein Bas Gaya Koi Re Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar, Film: Seema Film: Barsaat Mohammed Rafi Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar 43. Jhoole Mein Pawan Ki Aai Bahar 77. O Janewale Mud Ke Zara 08. Uthaye Ja Unke Sitam Film: Baiju Bawra Film: Shree 420 Film: Andaz Artistes: Lata Mangeshkar, Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Mohammed Rafi 78. -

Tazkira Qalandar Baba Auliar.A

Azkara Tazkira Qalandar Baba Aulia R.A SOHAIL AHMED AZEEMI www.ksars.org Khwaja Shamsuddin Azeemi Research Society 1 Tazkira Qalandar Baba Aulia DUNIYA E TILISMAAT HAI SAARI DUNIYA KYA KAHIYE KE HAI KYA YEH HAMARI DUNIYA MATTI KA KHILONA HAI HAMARI TAKHLEEQ MATTI KA KHILONA HAI YEH SAARI DUNIYA www.ksars.org Khwaja Shamsuddin Azeemi Research Society 2 Tazkira Qalandar Baba Aulia IK LAFZ THA IK LAFZ SE AFSANA HUA IK SHEHAR THA IK SHEHAR SE VIRANA HUA GARDON NEY HAZAAR AKS DAALEY HAIN AZEEM MEIN KHAAK HUA KHAAK SE PEMANA HUA www.ksars.org Khwaja Shamsuddin Azeemi Research Society 3 Tazkira Qalandar Baba Aulia Tazkira Qalandar Baba Aulia R.A Roman Urdu Compiled By RAMSHA AHMED AZEEMI www.ksars.org Khwaja Shamsuddin Azeemi Research Society 4 Tazkira Qalandar Baba Aulia Intesab Us Nojawan Nasal ke Naam Jo ABDAAL E HAQ, QALANDAR BABA AULIA ki “ Nisbat e Faizaan ” Se No-E-Insani Ko Sukoon O Raahat Se Aashna Kar Kay Is Ke Oopar Se Khauf Aur Gham Ke Dabeez Saaye Khatam Kardey Gi. .. .. .. .. .. Aur Phir Insaan Apna Azlli Sharf Haasil Kar Ke Jannat Mein Daakhil Hojaye Ga . www.ksars.org Khwaja Shamsuddin Azeemi Research Society 5 Tazkira Qalandar Baba Aulia Table of Contents 14 ....................................................................................... Halaat Zindagi 14 ........................................................................................... Qalandar 15 ................................................................................ Qalandari Silsila 16 ..............................................................................................