Plague and Plague Policies in Early Modem Denmark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

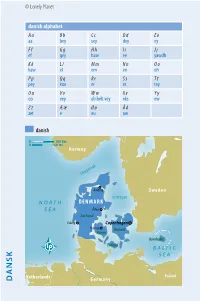

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

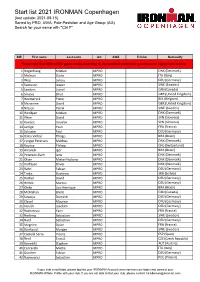

Start List 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (Last Update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for Your Name with "Ctrl F"

Start list 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (last update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for your name with "Ctrl F" BIB First name Last name AG AWA TriClub Nationallty Please note that BIBs will be given onsite according to the selected swim time you choose in registration oniste. 1 Hogenhaug Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 2 Molinari Giulio MPRO ITA (Italy) 3 Wojt Lukasz MPRO DEU (Germany) 4 Svensson Jesper MPRO SWE (Sweden) 5 Sanders Lionel MPRO CAN (Canada) 6 Smales Elliot MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 7 Heemeryck Pieter MPRO BEL (Belgium) 8 Mcnamee David MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 9 Nilsson Patrik MPRO SWE (Sweden) 10 Hindkjær Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 11 Plese David MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 12 Kovacic Jaroslav MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 14 Jarrige Yvan MPRO FRA (France) 15 Schuster Paul MPRO DEU (Germany) 16 Dário Vinhal Thiago MPRO BRA (Brazil) 17 Lyngsø Petersen Mathias MPRO DNK (Denmark) 18 Koutny Philipp MPRO CHE (Switzerland) 19 Amorelli Igor MPRO BRA (Brazil) 20 Petersen-Bach Jens MPRO DNK (Denmark) 21 Olsen Mikkel Hojborg MPRO DNK (Denmark) 22 Korfitsen Oliver MPRO DNK (Denmark) 23 Rahn Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 24 Trakic Strahinja MPRO SRB (Serbia) 25 Rother David MPRO DEU (Germany) 26 Herbst Marcus MPRO DEU (Germany) 27 Ohde Luis Henrique MPRO BRA (Brazil) 28 McMahon Brent MPRO CAN (Canada) 29 Sowieja Dominik MPRO DEU (Germany) 30 Clavel Maurice MPRO DEU (Germany) 31 Krauth Joachim MPRO DEU (Germany) 32 Rocheteau Yann MPRO FRA (France) 33 Norberg Sebastian MPRO SWE (Sweden) 34 Neef Sebastian MPRO DEU (Germany) 35 Magnien Dylan MPRO FRA (France) 36 Björkqvist Morgan MPRO SWE (Sweden) 37 Castellà Serra Vicenç MPRO ESP (Spain) 38 Řenč Tomáš MPRO CZE (Czech Republic) 39 Benedikt Stephen MPRO AUT (Austria) 40 Ceccarelli Mattia MPRO ITA (Italy) 41 Günther Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 42 Najmowicz Sebastian MPRO POL (Poland) If your club is not listed, please log into your IRONMAN Account (www.ironman.com/login) and connect your IRONMAN Athlete Profile with your club. -

Oversigt Over Retskredsnumre

Oversigt over retskredsnumre I forbindelse med retskredsreformen, der trådte i kraft den 1. januar 2007, ændredes retskredsenes numre. Retskredsnummeret er det samme som myndighedskoden på www.tinglysning.dk. De nye retskredsnumre er følgende: Retskreds nr. 1 – Retten i Hjørring Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten i Aalborg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Randers Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Aarhus Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Viborg Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Holstebro Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Herning Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Horsens Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Kolding Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Esbjerg Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Sønderborg Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Odense Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Svendborg Retskreds nr. 14 – Retten i Nykøbing Falster Retskreds nr. 15 – Retten i Næstved Retskreds nr. 16 – Retten i Holbæk Retskreds nr. 17 – Retten i Roskilde Retskreds nr. 18 – Retten i Hillerød Retskreds nr. 19 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. 20 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 21 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 22 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 23 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 24 – Retten på Bornholm Indtil 1. januar 2007 havde retskredsene følende numre: Retskreds nr. 1 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Gentofte Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Gladsaxe Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Ballerup Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Hvidovre Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Rødovre Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Brøndbyerne Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Taastrup Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Tårnby Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. -

Hele Rapporten I Pdf Format

Miljø- og Energiministeriet Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser Typeinddeling og kvalitetselementer for marine områder i Danmark Vandrammedirektiv–projekt, Fase 1 Faglig rapport fra DMU, nr. 369 [Tom side] Miljø- og Energiministeriet Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser Typeinddeling og kvalitetselementer for marine områder i Danmark Vandrammedirektiv–projekt, Fase 1 Faglig rapport fra DMU, nr. 369 2001 Kurt Nielsen Afdeling for Sø- og Fjordøkologi Bent Sømod Aarhus Amt Trine Christiansen Afdeling for Havmiljø Datablad Titel: Typeinddeling og kvalitetselementer for marine områder i Danmark Undertitel: Vandrammedirektiv-projekt, Fase 1 Forfattere: Kurt Nielsen1, Bent Sømod2, Trine Christiansen3 Afdelinger: 1Afd. for Sø- og Fjordøkologi 2Aarhus Amt 3Afd. for Havmiljø Serietitel og nummer: Faglig rapport fra DMU nr. 369 Udgiver: Miljø- og Energiministeriet Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser URL: http://www.dmu.dk Udgivelsestidspunkt: August 2001 Faglig kommentering: Dorte Krause-Jensen, Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser; Henning Karup, Miljøstyrelsen; Nanna Rask, Fyns Amt Layout: Pia Nygård Christensen Korrektur: Aase Dyhl Hansen og Pia Nygård Christensen Bedes citeret: Nielsen, K., Sømod, B. & T. Christiansen 2001: Typeinddeling og kvalitetselementer for marine områder i Danmark. Vandrammedirektiv-projekt, Fase 1. Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser. 107 s. - Faglig rapport fra DMU nr. 369. http://faglige-rapporter.dmu.dk. Gengivelse tilladt med tydelig kildeangivelse. Sammenfatning: Rapporten indeholder en opdeling af de danske kystområder i 16 forskellige typer i henhold -

Life and Cult of Cnut the Holy the First Royal Saint of Denmark

Life and cult of Cnut the Holy The first royal saint of Denmark Edited by: Steffen Hope, Mikael Manøe Bjerregaard, Anne Hedeager Krag & Mads Runge Life and cult of Cnut the Holy The first royal saint of Denmark Report from an interdisciplinary research seminar in Odense. November 6th to 7th 2017 Edited by: Steffen Hope, Mikael Manøe Bjerregaard, Anne Hedeager Krag & Mads Runge Kulturhistoriske studier i centralitet – Archaeological and Historical Studies in Centrality, vol. 4, 2019 Forskningscenter Centrum – Odense Bys Museer Syddansk Univeristetsforlag/University Press of Southern Denmark KING CNUT’S DONATION LETTER AND SETTLEMENT STRUCTURE IN DENMARK, 1085 – NEW PERSPECTIVES ON AN OLD DOCUMENT King Cnut’s donation letter and settle- ment structure in Denmark, 1085 – new perspectives on an old document By Jesper Hansen One of the most important sources to the history of donated to the Church of St Laurentius, the cathedral medieval Denmark is the donation letter of Cnut IV, church in Lund, and it represents the first written re- dated 21st of May 1085 and signed in Lund (fig. 1). cord of rural administration and fiscal rights in Den- This letter is a public affirmation of the royal gifts mark (Latin text, appendix 1). Cnut’s donation letter Skälshög, two hides. In Flädie, five this agreed-upon decree against the to the church in Lund and a half hides which Håkon gave to command of holy religion, he is to be the king. In Hilleshög, half a hide. In excommunicated upon the Return of (Dipl. Dan 1.2:21) Håstad, one hide. In Gärd. In Venestad, our Lord and to be consigned to eternal In the name of the indivisible Trinity, one hide. -

Life After Shrinkage

LIFE AFTER SHRINKAGE CASE STUDIES: LOLLAND AND BORNHOLM José Antonio Dominguez Alcaide MSc. Land Management 4th Semester February – June 2016 Study program and semester: MSc. Land Management – 4th semester Aalborg University Copenhagen Project title: Life after shrinkage – Case studies: Lolland and Bornholm A.C. Meyers Vænge 15 2450 Copenhagen SV Project period: February – June 2016 Secretary: Trine Kort Lauridsen Tel: 9940 3044 Author: E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Shrinkage phenomenon, its dynamics and strategies to José Antonio Dominguez Alcaide counter the decline performed by diverse stakeholders, Study nº: 20142192 are investigated in order to define the dimensions and the scope carried out in the places where this negative transformation is undergoing. The complexity of this process and the different types of decline entail a study in Supervisor: Daniel Galland different levels from the European to national (Denmark) and finally to a local level. Thus, two Danish municipalities Pages 122 (Lolland and Bornholm) are chosen as representatives to Appendix 6 contextualize this inquiry and consequently, achieve more accurate data to understand the causes and consequences of the decline as well as their local strategies to survive to this changes. 2 Preface This Master thesis called “Life after shrinkage - Case studies: Lolland and Bornholm” is conducted in the 4th semester of the study program Land Management at the department of Architecture, Design and Planning (Aalborg University) in Copenhagen in the period from February to June 2016. The style of references used in this thesis will be stated according to the Chicago Reference System. The references are represented through the last name of the author and the year of publication and if there are more than one author, the quote will have et al. -

Funen Energy Plan

STRATEGIC ENERGY PLANNING AT MUNICIPAL LEVEL Funen Energy Plan Funen is characterised by a high share of agriculture, From a systemic point of view, he emphasizes that the with remarkable biomass resources, and well- energy system needs to be redesigned. He finds it developed district heating and gas distributing important to link large heat pumps to surplus heat systems. To ensure the success and stability of future from industries so that they will be as cost-effective as local investments in the energy sector, Funen has possible. Furthermore, he stresses the importance of developed a political framework for the future energy using heat pumps to harness production of electricity investments, an energy plan. from wind turbines. The plan was developed in a wide cooperation between 9 municipalities on Funen and Ærø, 5 supply companies, University of Southern Denmark (SDU), Centrovice (the local agricultural trade organisation), and Udvikling Fyn (a regional business development company). In total, 36 students from SDU have made their Christian Tønnesen, Project manager and Head of the diploma work under the auspices of the energy plan Settlement & Business Department, Faaborg-Midtfyn thus creating a win-win satiation for students, Municipality, underlines: “The ambition for Funen university, local businesses, and municipalities. Energy Plan is to create a platform for the energy Exporting biomass fuel instead of electricity stakeholders, so that they from a common point of view can approach a joint planning for the future The energy plan presents a number of energy with a focus on innovation and optimal recommendations linked to particularly challenging solutions.” energy areas, where robust and long-term navigation Students contributing to real life energy plans is crucial. -

And New to Denmark? Lolland Municipality Has a Lot to Offer Foto: Jens Larsen - Nakskov Fotogruppe Welcome to Lolland

International – and new to Denmark? Lolland Municipality has a lot to offer Foto: Jens Larsen - Nakskov Fotogruppe Welcome to Lolland Are you an international working on, or going to work on, the Femern-connection? Are you in doubt what Lolland can offer you and your family? We are here to help you. Whether it is information or guidance regarding the many opportunities that exist in the area, our team of local experts can assist in terms of job opportunities, housing options, language schools, leisure activities, getting in touch with relevant public entities, building a network and more. We know that it is difficult moving to a new area and even a new country. We will work with you to help remove any language and cultural barriers so that you get the information you and your family need and get answers to questions about education, healthcare, employment and the like. In this publication you will find basic practical information. Please take a look at the different websites this folder provides you with and feel free to contact our interna- tional consultant for more detailed inquiries: Julia Böhmer Tel. +45 51 79 12 93 [email protected] 2 – International and new to Denmark Lolland International School Måske et stort kort? Eller to små? F.eks. et der viser, hvor Lolland ligger i det store perspektiv og et, der viser de små byer på Lolland, den internationale skole eller lignende. International and new to Denmark – 3 Everything you need Lolland is an attractive area to settle into, whether you are moving here alone or together with your family. -

Island Living on Bornholm

To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Island living on Bornholm © Semko Balcerski To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Land of many islands In Denmark, we look for a touch of magic in the ordinary, and we know that travel is more than ticking sights off a list. It’s about finding the wonder in the things you see and the places you go. One of the wonders, that we at VisitDenmark are particularly proud of, is our nature. Denmark has hundreds of islands, each with their own unique appeal. The island of Bornholm in the Baltic sea is known for its soft adventures, sustainability, gastronomy and impressive nature. s. 2 © Stefan Asp To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Denmark and its regions Geography Travel distances Aalborg • The smallest of the Scandinavian • Copenhagen to Odense: Bornholm countries Under 2 hours by car • The southernmost of the • Odense to Aarhus: Under 2 Scandinavian countries hours by car • Only has a physical border with • Aarhus to Aalborg: Under 2 Germany hours by car • Denmark’s regions are: North, Mid, Jutland West and South Jutland, Funen, Aarhus Zealand, and North Zealand and Copenhagen Billund Facts Copenhagen • Video Introduction • Denmark’s currency is the Danish Kroner Odense • Tipping is not required Zealand • Most Danes speak fluent English Funen • Denmark is of the happiest countries in the world and Copenhagen is one of the world’s most liveable cities • Denmark is home of ‘Hygge’, New Nordic Cuisine, and LEGO® • Denmark is easily combined with other Nordic countries • Denmark is a safe country • Denmark is perfect for all types of travelers (family, romantic, nature, bicyclist dream, history/Vikings/Royalty) • Denmark has a population of 5.7 million people s. -

GENERAL AGREEMENT on ^ TARIFFS and TRADE *> *****1958

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON ^ TARIFFS AND TRADE *> *****1958 Limited Distribution APPLICATION OF THE GENERAL AGREEMENT Territories to which the Agreement is applied Annexed hereto is a list of the contracting parties and of the territories (according to information available to the secretariat) in respect of which the application of the Agreement has been made effective. This list is a revision of that which appeared in document G/5 under date of 17 March 1952. If there are any inaccuracies in this list, the contracting parties concerned are requested to notify the Executive Secretary not later than 1 October 1958 so that a revised list can be issued, if necessary, before the opening of the Thirteenth Session* L/843 Paee 2 Contracting parties to GATT and territories In respeot ot which the application of the Agreement has been made affective AUSTRALIA (Including Tasmania) AUSTRIA BELGIUM BELGIAN CONGO RUANDA-URUNDI (Trust Territory) BRAZIL (Including islands: Fernando de Noronha (including Rocks of Sao Pedro, Sao Paolo, Atoll das Rocas) Trinidad and Martim Vas) BURMA CANADA CEYLON CHILE (Including the islands of: Juan Fernandez group, Easter Islands, Sala y Gomez, San Feliz, San Ambrosio and western part of Tierra del Fuego) CUBA (Including Isle of Pines and some smaller islands) CZECHOSLOVAKIA DENMARK (Including Greenland and the Island of Disko, Faroe Islands, Islands of Zeeland, Funen, Holland, Falster, Bornholm and some 1700 small islands) DOMINICAN REPUBLIC (Including islands: Saona, Catalina, Beata and some smaller ones) FINLAND FRANCE (Including Corsica and Islands off the French Coast, the Saar and the principality of Monaco)! ALGERIA CAMEROONS (Trust Territory) FRENCH EQUATORIAL AFRICA FRENCH GUIANA (Including islands of St. -

CEMENT for BUILDING with AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Portland Aalborg Cover Photo: the Great Belt Bridge, Denmark

CEMENT FOR BUILDING WITH AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Cover photo: The Great Belt Bridge, Denmark. AALBORG Aalborg Portland Holding is owned by the Cementir Group, an inter- national supplier of cement and concrete. The Cementir Group’s PORTLAND head office is placed in Rome and the Group is listed on the Italian ONE OF THE LARGEST Stock Exchange in Milan. CEMENT PRODUCERS IN Cementir's global organization is THE NORDIC REGION divided into geographical regions, and Aalborg Portland A/S is included in the Nordic & Baltic region covering Aalborg Portland A/S has been a central pillar of the Northern Europe. business community in Denmark – and particularly North Jutland – for more than 125 years, with www.cementirholding.it major importance for employment, exports and development of industrial knowhow. Aalborg Portland is one of the largest producers of grey cement in the Nordic region and the world’s leading manufacturer of white cement. The company is at the forefront of energy-efficient production of high-quality cement at the plant in Aalborg. In addition to the factory in Aalborg, Aalborg Portland includes five sales subsidiaries in Iceland, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia. Aalborg Portland is part of Aalborg Portland Holding, which is the parent company of a number of cement and concrete companies in i.a. the Nordic countries, Belgium, USA, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and China. Additionally, the Group has acti vities within extraction and sales of aggregates (granite and gravel) and recycling of waste products. Read more on www.aalborgportlandholding.com, www.aalborgportland.dk and www.aalborgwhite.com. Data in this brochure is based on figures from 2017, unless otherwise stated. -

Juleture 2020 Fyn - Sjælland Afg Mod Sjælland Ca

Juleture 2020 Fyn - Sjælland Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ København Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Roskilde Hillerød Helsingør Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Næstved Vordingborg Nykøbing F Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Korsør Slagelse Sorø Ringsted Køge Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Jylland - Fyn Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Aalborg Hobro Randers ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 200 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Aarhus ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Viborg Silkeborg ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Holstebro Herning ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Esbjerg Kolding Fredericia ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Skanderborg Horsens Vejle ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Sønderborg Aabenraa Haderslev ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Jylland - Sjælland Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Aalborg Hobro Randers ↔ København Afg mod Jylland ca.