UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Stand-Up Justice A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual New Years's Day Gala

Village of East Hills Senior Activities Committee PRESORTED 209 Harbor Hill Road Winter 2018-2019 FIRST CLASS East Hills, NY 11576 U.S. POSTAGE (516) 621-2796 Newsletter PAID [email protected] ROSLYN, NY Our thanks the Mayor and the Village Trustees for PERMIT NO.4 Stanley Stern, Chairperson their Sponsorship of our Newsletter and for being so Irving Chernofsky supportive of the Senior Activities Committee (SAC) Rhoda Helman Barbara Klein Joan Perilla Eileen Reed ANNUAL NEW YEARS’S DAY GALA TUESDAY, JANUARY 1sT 2019 1-4 pm IN THE VILLAGE THEATER This has become a marvelous tradition: starting the New Year with a Gala Brunch on January 1st. Come join your friends and neighbors in the easy and relaxed atmosphere of the Village Theater. You don’t have to travel far, and you don’t have to worry about crowds or parking. Just come and enjoy great food, delightful company, some mellow musical entertainment and a champagne toast. What a great way to welcome 2019! Don’t miss the fun, the food and the festivities! $30 Residents/$35 Non-residents TUESDAY, DECEMBER 18TH 6:30 PM Don’t miss our SAC FEAST AT PEARL EAST! Everyone knows what a fabulous feast we have every year, and this one will be no different. This is not your “usual Chinese Dinner” — this is an extraordinary culinary taste thrill, prepared just for us by our host, Cathy. Not only does the food taste delicious, it comes to us in gorgeous displays of beautifully designed and executed animals, flowers and decorations. Don’t miss this wonderful opportunity to join us for fun and wonderful food — at this famous choice restaurant of Long Island! Cost: $50 Residents/$55 Non-residents Winter Weary? Come for Lunch and a Free Movie in Glen Cove Tuesday, January 15th - 11:30 AM Come in out of the January cold and join us for an afternoon of lunch and movie. -

Rita Rudner Returns to the NYC Stage in the NYC Premiere of the New Musical Comedy TWO’S a CROWD

Rita Rudner returns to the NYC stage in the NYC premiere of the new musical comedy TWO’S A CROWD New York, New York June 4, 2019—59E59 Theaters (Val Day, Artistic Director; Brian Beirne, Managing Director) is thrilled to welcome comedy icon Rita Rudner in the NYC premiere of TWO’S A CROWD, with a book by Ms. Rudner and Martin Bergman, music and lyrics by Jason Feddy, and direction by Mr. Bergman. Produced by Impro Theatre in association with Ritmar Productions, Inc., TWO’S A CROWD begins performances on Saturday, July 13 for a limited engagement through Sunday, August 25. Press Opening is Sunday, July 21 at 2 PM. The performance schedule is Tuesday – Friday at 7 PM; Saturday at 2 PM & 7 PM; and Sunday at 2 PM. Please note there is an added performance on Sunday, July 14 at 7 PM. Performances are at 59E59 Theaters (59 East 59th Street, between Park and Madison). Single tickets are $25 - $70 ($49 for 59E59 Members). To purchase tickets, call the 59E59 Box Office at 646-892-7999 or visit www.59e59.org. The running time is 85 minutes, no intermission. They say opposites attract. They haven’t met Tom and Wendy. Forced together by a computer error, freewheeling Tom and uptight Wendy do their best to ruin each other’s vacations. But the bright lights of Vegas might just convince them to take a chance on the happiness they both gave up on long ago. Ground-breaking comedy icon Rita Rudner returns to the NY stage to star in this light- hearted musical comedy that is a perfect summer confection. -

Bob Barker Has Made a Huge Impact on Television, and on Animal Rights, Too

2015 LEGEND AWARD A Host and a Legend BOB BARKER HAS MADE A HUGE IMPACT ON TELEVISION, AND ON ANIMAL RIGHTS, TOO BY PATT f there were a Mt. Rushmore for television this name; you’re going to hear a lot about him.” When he landed as host MORRISON game show hosts, there’s no doubt about it: Bob Barker, for his part, said modestly that, “I feel like Barker would be up there. I’m hitting afer Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.” on “The Price is Right” Even without being made of granite, his face Barker went on to become a one-man Murderers’ has endured, flling Americans’ eyeballs and Row of game show hosts, making a long-lasting mark in 1972, he found his television screens for a remarkable half-century. He on “Truth or Consequences” and hosting a number of Ihelped to defne the game-show genre, as a pioneer in others that came and went. television home, the myriad ways, right down to taking the radical step of But when he landed as host on “Te Price is Right” letting his hair go naturally white for TV. He has nearly in 1972, he found his television home, the place where place where he broke 20 Emmys to his credit. he broke Johnny Carson’s 29-year record as longest- Johnny Carson’s 29-year Now, he is the recipient of the Legend Award from serving host of a TV show. the Los Angeles Press Club, presented at the 2015 It’s easy to rattle of numbers—for example, the frst record as longest-serving National Arts & Entertainment Awards. -

Rhetoric and Law: How Do Lawyers Persuade Judges? How Do Lawyers Deal with Bias in Judges and Judging?

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Honors Theses Department of English 5-9-2015 Rhetoric And Law: How Do Lawyers Persuade Judges? How Do Lawyers Deal With Bias In Judges And Judging? Danielle Barnwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_hontheses Recommended Citation Barnwell, Danielle, "Rhetoric And Law: How Do Lawyers Persuade Judges? How Do Lawyers Deal With Bias In Judges And Judging?." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_hontheses/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RHETORIC AND LAW: HOW DO LAWYERS PERSUADE JUDGES? HOW DO LAWYERS DEAL WITH BIAS IN JUDGES AND JUDGING? By: Danielle Barnwell Under the Direction of Dr. Beth Burmester An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Undergraduate Research Honors in the Department of English Georgia State University 2014 ______________________________________ Honors Thesis Advisor ______________________________________ Honors Program Associate Dean ______________________________________ Date RHETORIC AND LAW: HOW DO LAWYERS PERSUADE JUDGES? HOW DO LAWYERS DEAL WITH BIAS IN JUDGES AND JUDGING? BY: DANIELLE BARNWELL Under the Direction of Dr. Beth Burmester ABSTRACT Judges strive to achieve both balance and fairness in their rulings and courtrooms. When either of these is compromised, or when judicial discretion appears to be handed down or enforced in random or capricious ways, then bias is present. -

The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness

Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 1 2004 As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness Kimberlianne Podlas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Communications Law Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Kimberlianne Podlas, As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness, 11 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 1 (2004). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol11/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Podlas: As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contempo VILLANOVA SPORTS & ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL VOLUME XI 2004 ISSUE 1 Article AS SEEN ON TV: THE NORMATIVE INFLUENCE OF SYNDI-COURT ON CONTEMPORARY LITIGIOUSNESS KIMBERLIANNE PODLAS* I. INTRODUCTION A variety of disciplines have investigated the ability of the me- dia, particularly television, to influence public perceptions.' Re- gardless of the theory employed, all posit that television content has a reasonably direct and directional influence on viewer attitudes and propensities to engage in certain behaviors. 2 This article ex- tends this thesis to the impact of television representations of law: If television content generally can impact public attitudes, then it is reasonable to believe that television law specifically can do so. 3 Nevertheless, though television representations of law have become * Kimberlianne Podlas, Assistant Professor, Caldwell College, Caldwell, New Jersey. -

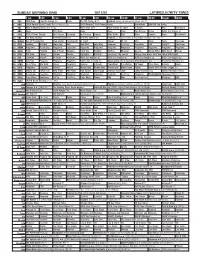

Sunday Morning Grid 10/11/20 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/11/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC 2020 Roland-Garros Tennis Men’s Final. (6) (N) 2020 Women’s PGA Championship Countdown NASCAR Cup Series 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch AAA Sex Abuse 7 ABC News This Week News News News Sea Rescue Ocean World of X Games Å 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb AAA Silver Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Washington Football Team. (N) Å 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Abuse? Dr. Ho AAA Smile News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Cooking BISSELL More Hair AAA New YOU! Larry King Kenmore Paid Prog. Transform AAA WalkFit! Can’tHear 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Programa ·Solución! Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Simply Ming Milk Street Nevens 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Curious Curious Highlights Biz Kid$ Easy Yoga: The Secret Change Your Brain, Heal Your Mind With Daniel 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Medicare NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Como dice el dicho (N) Suave patria (2012, Comedia) Omar Chaparro. -

I'm Not a Judge but I Play One on TV : American Reality-Based Courtroom Television

I'M NOT A JUDGE BUT I PLAY ONE ON TV: AMERICAN REALITY-BASED COURTROOM TELEVISION Steven Arthur Kohm B.A. (Honours) University of Winnipeg, 1997 M.A. University of Toronto, 1998 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School of Criminology O Steven Kohm 2004 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2004 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Steven Arthur Kohm Degree: Ph.D. Title of Dissertation: I'm Not a Judge, but I Play One on TV: American Reality-based Courtroom Television Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Dorothy Chunn Professor of Criminology Dr. John Lowman Senior Supervisor Professor of Criminology Dr. Robert Menzies Supervisor Professor of Criminology Dr. Margaret Jackson Supervisor Professor of Criminology Dr. Rick Gruneau Internal Examiner Professor of Communication Dr. Aaron Doyle External Examiner Assistant Professor of Sociology and Anthropology, Carlton University Date DefendedApproved: SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, afid to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection. -

Rita Rudner's One-Liners Keep the Audiences Laughing at Harrah's

Feb. 22, 2009 Funny Girl Rita Rudner’s one-liners keep the Photos courtesy Harrah’s Entertainment Along with her clever one-liners and observations of everyday life, Rita Rudner is known for wearing glamorous gowns in her act at audiences laughing at Harrah’s Harrah’s hotel. She says she has about 15 gowns altogether. BY KRisTINE MCKENZie Make ‘eM LAUGH order to keep their youthful appearances. One of the things Rudner is best known for Vegas.com Women will do anything to avoid wrinkles, is poking fun at the many differences between Who: Rita Rudner Rudner says. “My aunt Sylvia just had herself men and women and she covers many common Where: Harrah’s laminated.” areas of disagreement between the sexes like ita Rudner is the queen of clever When: 8:30 p.m. Monday - Saturday. Rudner also questions the audience about driving, reading maps, watching sports and the one-liners and she delivers them in their familiarity with Botox. “It’s botulism, love women have for decorative pillows. rapid succession in her trademark which I’ve made in my kitchen quite a few Now that she is a mother, Rudner also works deadpan voice and sparkling gown “I don’t care where you’re from, Las Vegas times,” she jokes. in material about parenting, commenting that during her show at Harrah’s. is the opposite of it,” she says. Topics about aging like becoming more working in Vegas is perfect because she has RRudner’s routine features her stream-of- Rudner asks audience members if they’ve forgetful and losing your eyesight and hearing hired a Rita Rudner impersonator as a nanny so consciousness-style observations on everyday been to the Grand Canyon and says that she draw laughs and nods of recognition from the her daughter never knows that she’s not there. -

Exploring Viewers' Responses to Nine Reality TV Subgenres

Psychology of Popular Media Culture © 2015 American Psychological Association 2015, Vol. 5, No. 1, 000 2160-4134/15/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000103 Exploring Viewers’ Responses to Nine Reality TV Subgenres Mina Tsay-Vogel K. Maja Krakowiak Boston University University of Colorado, Colorado Springs Reality TV is a genre that places nonactors in dramatic situations with unpredictable outcomes. The influx of reality TV dominating network and cable programming has been highly reflective in its expansion of formats, evident from the variety of narrative themes embedded in reality-based shows. Findings from this exploratory study (N ϭ 274) reveal significant differences in the way college students affectively, cognitively, and behaviorally engage with reality TV. Specifically, identification, interactivity, enjoyment, perceived realism, and perceived competition across 9 reality TV sub- genres: dating/romance, makeover/lifestyle, hidden camera, talent, game show, docu- soap, sitcom, law enforcement, and court significantly differed. Data provide strong support that programs commonly defined as reality-based offer qualitatively distinct affective, cognitive, and behavioral experiences and gratifications for viewers. Keywords: reality TV, reality programs, subgenres, TV formats, gratifications The unscripted and inexpensive nature of re- (Cavendar & Fishman, 1998). Shows such as ality TV programs continues to make them pop- The Bachelor, Survivor, The Voice, Duck Dy- ular commodities in the entertainment industry nasty, Love and Hip Hop, and The Real House- (Essany, 2013; Ramdhany, 2012). Evidence wives have generally been regarded as a single supporting reality TV’s appeal has been docu- and collective genre, assumed to convey homo- mented as a function of motives for self- geneous messages and themes (Kavka, 2012). -

At Tony Lena's, It's All in the Bread

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2020 A world 828 units connected oated by trains for South Marblehead store owner nds perfect Harbor model in Peabody By Gayla Cawley ITEM STAFF By Thor Jourgensen ITEM STAFF LYNN — After years of stalled plans aimed at redeveloping the PEABODY — A train lover since long-vacant 17-acre waterfront site he was tyke, Don Stubbs decided known as “South Harbor” on the to turn a hobby into a business in Lynnway, the city’s head of econom- 1988 when he opened North East ic development believes the timing Trains on Main Street, about four is nally right. blocks from the model and minia- The renewed push to redevelop ture train store’s current location. the South Harbor site, which has Located in a former hardware sat vacant for three decades and is store with high, tin-stamp ceil- located near the General Edwards ings and classical music playing Bridge at the mouth of the Saugus at a soft volume, North East is a River, comes from property owner model-train lover’s dream come Joseph O’Donnell, who purchased true. Display cases and shelves the land in 2005. showcase miniature locomotives, O’Donnell, founder of Belmont passenger and freight cars with Capital, LLC in Cambridge, has names like “K-line diesel” and submitted preliminary plans that “Jordan spreader plow.” would transform the former Harbor A walk around the store is a vis- House site into a neighborhood of it to a world where rail enthusi- 828 market-rate apartments over asts from around the region stop three wood-framed buildings, retail in to shop or sell their train col- space and 935 parking spaces. -

2020 Syndicated Program Guide.Xlsx

CONTENT STRATEGY SYNDICATED PROGRAM GUIDE SYNDICATED PROGRAM LISTINGS / M-F STRIPS (Preliminary) Distributor Genre Time Terms Barter Split Renewed Syndication UPDATED 1/28/20 thru Debut FUTURES FALL 2020 STRIPS CARBONARO EFFECT, THE Trifecta Reality 30 Barter TBA 2020-21 Hidden-camera prank series hosted by magician and prankster Michael Carbonaro. From truTV. Weekly offering as well. COMMON KNOWLEDGE Sony TV Game 30 Barter 3:00N / 5:00L 2020-21 Family friendly, multiple choice quiz game off GSN, hosted by Joey Fatone. DREW BARRYMORE SHOW, THE CBS TV Distribution Talk 60 Cash+ 4:00N / 10:30L 2021-22 Entertainment talk show hosted by Producer, Actress & TV personality Drew Barrymore. 2 runs available. CBS launch group. Food/Lifestyle talk show spin-off of Dr. Oz's "The Dish on Oz" segment", hosted by Daphne Oz, Vanessa Williams, Gail Simmons(Top Chef), Jamika GOOD DISH, THE Sony TV Talk 60 Cash+ 4:00N / 10:30L 2021-22 Pessoa(Next Food Star). DR. OZ production team. For stations includes sponsorable vignettes, local content integrations, unique digital & social content. LAUREN LAKE SHOW, THE MGM Talk 30 Barter 4:00N / 4:00L 2020-21 Conflict resolution "old-shool" talker with "a new attitude" and Lauren Lake's signature take-aways and action items for guests. 10 episodes per week. LOCK-UP NBC Universal Reality 60 Barter 8:00N/8:00L 2020-21 An inside look at prison life. Ran on MSNBC from 2005-2017. Flexibility, can be used as a strip, a weekly or both, 10 runs available, 5 eps/wk. Live-to-tape daily daytime talker featuring host Nick Cannon's take on the "latest in trending pop culture stories and celeb interviews." FOX launch. -

TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FOX, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

21st Century Fox - Annual Report Page 1 of 201 ^ \ ] _ UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2017 or ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 or 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 001-32352 TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FOX, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) Delaware 26-0075658 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 1211 Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10036 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code (212) 852-7000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange On Which Title of Each Class Registered Class A Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share The NASDAQ Global Select Market Class B Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share The NASDAQ Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.