I'm Not a Judge but I Play One on TV : American Reality-Based Courtroom Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download The

WHAT WOULD JUDY SAY? BE THE HERO OF YOUR OWN STORY Judge Judy Sheindlin Foreword by Nicole Sheindlin Sheindlin_ WWJS_3P_yc.indd 3 8/8/14 11:12 AM What Would Judy Say? Be the Hero of Your Own Story Judge Judy Sheindlin Copyright © 2014 Judy Sheindlin Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. * * * * * Credits Cover photo by Robert Piazza Photographer, LLC www.robertpiazza.com Cover design by Laura Duffy Illustrations by Wally Littman Formatting by Debora Lewis arenapublishing.org * * * * * Sheindlin_ WWJS_3P_yc.indd 4 8/8/14 11:12 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword: Lessons from My Stepmom, Judy Sheindlin vii Introduction: Have It All? 1 Chapter One: The Envelope, Please 5 Chapter Two: Pretty, Smart . or Something More? 11 Chapter Three: Priority YOU 21 Chapter Four: Work You Love 33 Chapter Five: It’s Never Too Early 43 Judy’s 10 Laws of Success 47 #1: Be Indispensable 49 #2: Think Fearlessly and Strategically 53 #3: Use Your Assets 57 #4: Don’t Blow the First Impression 61 #5: Lighten Up 69 #6: Practice Punctuality 73 #7: Create an Interesting Person 77 #8: Demand Your Worth 79 #9: Do the Right Thing 83 #10: Leave a Footprint 87 Epilogue: A Final Word 89 A Note to Readers 91 Sheindlin_ WWJS_3P_yc.indd 5 8/8/14 11:12 AM Sheindlin_ WWJS_3P_yc.indd 6 8/8/14 11:12 AM FOREWORD Lessons from My Stepmom, Judy Sheindlin by Nicole Sheindlin I first met Judy when I was seven years old, at my kitchen table. -

Performing the Self on Survivor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M Repository TEMPORARILY MACHIAVELLIAN: PERFORMING THE SELF ON SURVIVOR An Undergraduate Research Scholars Thesis by REBECCA J. ROBERTS Submitted to the Undergraduate Research Scholars program at Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the designation as an UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH SCHOLAR Approved by Research Advisor: Dr. James Ball III May 2018 Major: Performance Studies Psychology TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................. 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................ 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTERS I. OUTWIT. OUTPLAY. OUTLAST ......................................................................... 8 History of Survivor ............................................................................................ 8 Origin Story of Survivor .................................................................................. 10 Becoming the Sole Survivor ............................................................................ 12 II. IDENTITY & SELF-PRESENTATION ................................................................ 17 Role Performance ........................................................................................... -

In Between Spectacle and Political Correctness: Vamos Con Todo – an Ambivalent News/Talk Show1

Pragmatics 23:1.117-145 (2013) International Pragmatics Association DOI: 10.1075/prag.23.1.06pla IN BETWEEN SPECTACLE AND POLITICAL CORRECTNESS: VAMOS CON TODO – AN AMBIVALENT NEWS/TALK SHOW1 María Elena Placencia and Catalina Fuentes Rodríguez Abstract Vamos con todo is a mixed-genre entertainment programme transmitted in Ecuador on a national television channel. The segment of the programme that we examine in this paper focuses on gossip and events surrounding local/national celebrities. Talk as entertainment is central to this segment which is structured around a series of ‘news’ stories announced by the presenters and mostly conveyed through (pre-recorded) interviews. Extracts of these interviews are ingeniously presented to create a sense of confrontation between the celebrities concerned. Each news story is then followed-up by informal ‘discussions’ among the show’s 5-6 presenters who take on the role of panellists. While Vamos con todo incorporates various genres, the running thread throughout the programme is the creation of scandal and the instigation of confrontation. What is of particular interest, however, is that no sooner the scandalous stories are presented, the programme presenters attempt to defuse the scandal and controversy that they contributed to creating. The programme thus results in what viewers familiar with the genre of confrontational talk shows in Spain, for example, may regard as an emasculated equivalent. In this paper we explore linguistic and other mechanisms through which confrontation and scandal are first created and then defused in Vamos con todo. We consider the situational, cultural and socio-political context of the programme as possibly playing a part in this disjointedness. -

Gender-Based Use of Negative Concord in Non- Standard American English

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI Gender-Based Use of Negative Concord in Non- Standard American English Henriikka Malkamäki Pro Gradu Thesis English Philology Department of Modern Languages University of Helsinki October 2013 2 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Nykykielten laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Henriikka Malkamäki Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Kaksoisnegaatio miesten ja naisten puhumassa amerikanenglannissa Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Englantilainen filologia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä – Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro Gradu -tutkielma Lokakuu 2013 68 + 4 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Tämä työ tarkastelee kaksoisnegaatiota miesten ja naisten puhumassa amerikanenglannissa. Tutkimus toteutettiin vertaamalla kolmea eri negaatiomuotoparia. Tutkittuihin negaatiomuotoihin lukeutuivat standardikieliopista poikkeavat tuplanegaatiomuodot n’t nothing, not nothing ja never nothing, ja niiden vastaavat standardikieliopin mukaiset negaatiomuodot n’t anything, not anything ja never anything. Kyseisiä negaatiomuotoja haettiin Corpus of Contemporary American English -nimisessä korpuksessa olevasta puhutun kielen osiosta, ’spoken section’, joka koostuu litteroiduista TV- ja radio-ohjelmista. Tutkimuksen aineisto muodostui litteroitujen ohjelmien tekstiotteista, joissa negaatiomuodot ilmenivät. Sekä standardikieliopista poikkeavien muotojen käyttöaste että kieliopin mukaisesti rakennettujen muotojen käyttöaste (%) laskettiin -

Rhetoric and Law: How Do Lawyers Persuade Judges? How Do Lawyers Deal with Bias in Judges and Judging?

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Honors Theses Department of English 5-9-2015 Rhetoric And Law: How Do Lawyers Persuade Judges? How Do Lawyers Deal With Bias In Judges And Judging? Danielle Barnwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_hontheses Recommended Citation Barnwell, Danielle, "Rhetoric And Law: How Do Lawyers Persuade Judges? How Do Lawyers Deal With Bias In Judges And Judging?." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_hontheses/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RHETORIC AND LAW: HOW DO LAWYERS PERSUADE JUDGES? HOW DO LAWYERS DEAL WITH BIAS IN JUDGES AND JUDGING? By: Danielle Barnwell Under the Direction of Dr. Beth Burmester An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Undergraduate Research Honors in the Department of English Georgia State University 2014 ______________________________________ Honors Thesis Advisor ______________________________________ Honors Program Associate Dean ______________________________________ Date RHETORIC AND LAW: HOW DO LAWYERS PERSUADE JUDGES? HOW DO LAWYERS DEAL WITH BIAS IN JUDGES AND JUDGING? BY: DANIELLE BARNWELL Under the Direction of Dr. Beth Burmester ABSTRACT Judges strive to achieve both balance and fairness in their rulings and courtrooms. When either of these is compromised, or when judicial discretion appears to be handed down or enforced in random or capricious ways, then bias is present. -

Angry Judges

Angry Judges Terry A. Maroney* Abstract Judges get angry. Law, however, is of two minds as to whether they should; more importantly, it is of two minds as to whether judges’ anger should influence their behavior and decision making. On the one hand, anger is the quintessentially judicial emotion. It involves appraisal of wrongdoing, attribution of blame, and assignment of punishment—precisely what we ask of judges. On the other, anger is associated with aggression, impulsivity, and irrationality. Aristotle, through his concept of virtue, proposed reconciling this conflict by asking whether a person is angry at the right people, for the right reasons, and in the right way. Modern affective psychology, for its part, offers empirical tools with which to determine whether and when anger conforms to Aristotelian virtue. This Article weaves these strands together to propose a new model of judicial anger: that of the righteously angry judge. The righteously angry judge is angry for good reasons; experiences and expresses that anger in a well-regulated manner; and uses her anger to motivate and carry out the tasks within her delegated authority. Offering not only the first comprehensive descriptive account of judicial anger but also first theoretical model for how such anger ought to be evaluated, the Article demonstrates how judicial behavior and decision making can benefit by harnessing anger—the most common and potent judicial emotion—in service of righteousness. Introduction................................................................................................................................ -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

THE VOICE Feb 4, 2004 Volume 12, Issue 05

THE VOICE Feb 4, 2004 Volume 12, Issue 05 Welcome To The Voice PDF he Voice has an interactive table of contents. Click on a story title or author name to jump to an article. Click the T bottom-right corner of any page to return to the contents. Some ads and graphics are also links. FEATURES EDITORIAL PAGES ARTICLES NATURE NOTES - FAUNAL ADAPTATIONS Zoe Dalton REMEMBERING A LESS THAN PERFECT MOTHER Barbara Godin IS THERE A DOULA IN THE HOUSE - pt 2 Sara Kinninmont FMP: FREEDOM OF SPEECH Debbie Jabbour THE GLEASON BROTHERS Wayne E. Benedict FICTION FEATURE POETRY BY… Bill Pollett COLUMNS SOUNDING OFF - Commercials we hate; toughest AU courses PRIMETIME UPDATE Amanda Lyn Baldwin NEW: DEAR HEATHER TAKING NOTES: EYE ON EDUCATION Debbie Jabbour CANADIAN FEDWATCH! Karl Low AUSU THIS MONTH FLICKS & FOLIOS: Weekend at Bernies Laura Seymour NEWS AND ANNOUNCEMENTS VOICE EVENTS LISTINGS SCHOLARSHIPS AND AWARDS CONFERENCE CONNECTIONS The Insider FROM THE READERS LETTERS TO THE EDITOR CLASSIFIEDS! THE VOICE c/o Athabasca University Students' Union We love to hear from you! Send your questions and 2nd Floor, 10030-107th Street, comments to [email protected], and please indicate if we may Edmonton, AB T5J 3E4 publish your letter in the Voice. 800.788.9041 ext. 3413 Publisher Athabasca University Students' Union Editor In Chief Tamra Ross Low Response to Shannon Maguire's "Where Has All The Fat News Contributor Lonita Fraser Come From", v12 i04, January 28, 2004. I really appreciate Shannon's comments, but, and perhaps it's just THE VOICE ONLINE: the psychology student in me, why does everyone seem to ignore WWW.AUSU.ORG/VOICE the mental and emotional baggage involved in weight loss? I have repeatedly been uncomfortable with the prospect of being slim due to an asinine inner belief that I will be attacked by crazed The Voice is published every men .. -

THE NATIONAL TELEVISION ACADEMY PRESENTS the 33Rd ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY AWARDS in a THREE-HOUR TELECAST on ABC

THE NATIONAL TELEVISION ACADEMY PRESENTS THE 33rd ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY AWARDS IN A THREE-HOUR TELECAST ON ABC For the First Time, The Daytime Emmy Awards Were Held in Hollywood at the Famed Kodak Theatre NEW YORK, NY – April 28, 2006 – The 33rd Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards were presented by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences at Hollywood’s Kodak Theatre tonight and telecast live on the ABC Television Network (8-11 PM, ET; tape delay to the West Coast). The black-tie gala ceremony, which marked the first time in its 33-year history that the Daytime Emmy Awards were presented in Hollywood, was hosted by Tom Bergeron (“Dancing with the Stars,” “America’s Funniest Home Videos”) and Kelly Monaco (“General Hospital”). The three-hour star-studded telecast opened with Award-winning actor and musician Rick Springfield (“General Hospital’s” Dr. Noah Drake) performing a mix of his best music – including his worldwide megahit, “Jesse’s Girl.” Daytime Emmy Awards were presented for performances and programs in 15 categories, including Outstanding Lead Actor/Actress in a Drama Series, Outstanding Game Show Host, Outstanding Talk Show, Outstanding Pre-School Children’s Series and Outstanding Drama Series. Presenters included Chandra Wilson, Kate Walsh and James Pickens, Jr. (“Grey’s Anatomy”), Rachel Ray (“The Rachel Ray Show”), Tyra Banks (“The Tyra Banks Show”), Judge Judy Sheindlin (“Judge Judy”); Lisa Rinna and Ty Treadway (“Soap Talk”); Barbara Walters, Meredith Vieira, Star Jones Reynolds, Joy Behar and Elisabeth Hasselbeck (“The View”), and dozen of stars from all the Emmy- nominated daytime dramas. On April 22, Daytime Emmy Awards were presented primarily in the creative arts categories at the Marriott Marquis Hotel in New York City and at the Grand Ballroom at Hollywood and Highland in Los Angeles. -

The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness

Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 1 2004 As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness Kimberlianne Podlas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Communications Law Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Kimberlianne Podlas, As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness, 11 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 1 (2004). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol11/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Podlas: As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contempo VILLANOVA SPORTS & ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL VOLUME XI 2004 ISSUE 1 Article AS SEEN ON TV: THE NORMATIVE INFLUENCE OF SYNDI-COURT ON CONTEMPORARY LITIGIOUSNESS KIMBERLIANNE PODLAS* I. INTRODUCTION A variety of disciplines have investigated the ability of the me- dia, particularly television, to influence public perceptions.' Re- gardless of the theory employed, all posit that television content has a reasonably direct and directional influence on viewer attitudes and propensities to engage in certain behaviors. 2 This article ex- tends this thesis to the impact of television representations of law: If television content generally can impact public attitudes, then it is reasonable to believe that television law specifically can do so. 3 Nevertheless, though television representations of law have become * Kimberlianne Podlas, Assistant Professor, Caldwell College, Caldwell, New Jersey. -

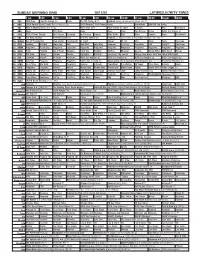

Sunday Morning Grid 10/11/20 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/11/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC 2020 Roland-Garros Tennis Men’s Final. (6) (N) 2020 Women’s PGA Championship Countdown NASCAR Cup Series 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch AAA Sex Abuse 7 ABC News This Week News News News Sea Rescue Ocean World of X Games Å 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb AAA Silver Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Washington Football Team. (N) Å 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Abuse? Dr. Ho AAA Smile News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Cooking BISSELL More Hair AAA New YOU! Larry King Kenmore Paid Prog. Transform AAA WalkFit! Can’tHear 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Programa ·Solución! Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Simply Ming Milk Street Nevens 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Curious Curious Highlights Biz Kid$ Easy Yoga: The Secret Change Your Brain, Heal Your Mind With Daniel 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Medicare NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Como dice el dicho (N) Suave patria (2012, Comedia) Omar Chaparro. -

The Mount's Culture of Service

AUTUMN 2010 Alumni, Students college of & Friends mount saint vincentnews Mount students and staff in Guatemala INSIDE The Culture of Service: COVER Dr. Natalia Smirnova Brings More International Flavor to the Mount: PAGES 2 & 3 Dr. Joseph Skelly Explores Reform for the Middle East in his New Book: paGE 4 Kevin Garlan Presents at the National Conference for the American Anthropological Association: PAGE 5 The 2010 Scholarship The Mount’s Culture of Service: Tribute Dinner Breaks the Records. Over “…let us love one another, for charity is of God.” $550,000 Raised for Scholarships: paGE 6 For students attending the College of Mount espouses the teachings of Saint Vincent de Saint Vincent, an undergraduate education Paul, the 18th-century French priest who Jessica Abejar ’11 Earns Kudos in C200 consists of much more than mere courses, championed aid to the sick, the reviled Summer Internship: lectures, and lab work. For the College is, and the poor. Among Saint Vincent’s famous PAGE 8 as Dianna Dale, Vice President for Student sayings: “It is only for your love alone that Athletics Top Ten: Affairs puts it, “mission driven.” The College the poor will forgive you the bread you give paGE 9 aspires to develop a whole person: young to them,” and “Dearly beloved, let us love Renowned Alumna men and women who appreciate the fact one another, for charity is of God.” Rosemary T. Berkery that what one individual does inevitably has The College also celebrates the good Inspires the Class an effect on the lives of others. works of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton, the first of 2010 with her Commencement Mount Saint Vincent was founded by American to be canonized by the Roman Address: the Sisters of Charity of New York and it Catholic Church.