The Hobbit and Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speaking of South Park

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 3 May 15th, 9:00 AM - May 17th, 5:00 PM Speaking of South Park Christina Slade University Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Slade, Christina, "Speaking of South Park" (1999). OSSA Conference Archive. 53. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA3/papersandcommentaries/53 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title: Speaking of South Park Author: Christina Slade Response to this paper by: Susan Drake (c)2000 Christina Slade South Park is, at first blush, an unlikely vehicle for the teaching of argumentation and of reasoning skills. Yet the cool of the program, and its ability to tap into the concerns of youth, make it an obvious site. This paper analyses the argumentation of one of the programs which deals with genetic engineering. Entitled 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig', the episode begins with the elephant being presented to the school bus driver as 'the new disabled kid'; and opens a debate on the virtues of genetic engineering with the teacher saying: 'We could have avoided terrible mistakes, like German people'. The show both offends and ridicules received moral values. However a fine grained analysis of the transcript of 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig' shows how superficially absurd situations conceal sophisticated argumentation strategies. -

South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review

south park the fractured but whole free download review South park the fractured but whole free download review. South Park The Fractured But Whole Crack Whole, players with Coon and Friends can dive into the painful, criminal belly of South Park. This dedicated group of criminal warriors was formed by Eric Cartman, whose superhero alter ego, The Coon, is half man, half raccoon. Like The New Kid, players will join Mysterion, Toolshed, Human Kite, Mosquito, Mint Berry Crunch, and a group of others to fight the forces of evil as Coon strives to make his team of the most beloved superheroes in history. Creators Matt South Park The Fractured But Whole IGG-Game Stone and Trey Parker were involved in every step of the game’s development. And also build his own unique superpowers to become the hero that South Park needs. South Park The Fractured But Whole Codex The player takes on the role of a new kid and joins South Park favorites in a new extremely shocking adventure. The game is the sequel to the award-winning South Park The Park of Truth. The game features new locations and new characters to discover. The player will investigate the crime under South Park. The other characters will also join the player to fight against the forces of evil as the crown strives to make his team the most beloved South Park The Fractured But Whole Plaza superheroes in history. Try Marvel vs Capcom Infinite for free now. The all-new dynamic control system offers new possibilities to manipulate time and space on the battlefield. -

Sacred Heart Parish St

WELCOME To The Regional Parishes of Tacoma March 24, 2019 Third Sunday of Lent Your Pastoral Team Fr. Tuan Nguyen, D. Min. Fr. Patrick McDermott Fr. James Harbaugh Regional Pastor Parochial Vicar Parochial Vicar 253-882-9943 360-556-4111 206-335-8385 [email protected] “I shall [email protected] [email protected] Emergency Contact Sr. Anna: (253) 592-2455 cultivate www.trparishes.org the ground Sacred Heart Parish St. Ann Parish St. John of the Woods 4520 McKinley Avenue 7025 South Park Avenue Parish Tacoma, WA 98404 Tacoma, WA 98408 9903 24th Avenue East around it (253) 472-7738 (253) 472-1360 Tacoma (Midland), WA 98445 Masses / Misas English Masses & (253) 537-8551 Reconciliation Sunday 10:00am English English Masses & Reconciliation: Sat.4:00pm and Mon & Fri 8:00am English Reconciliation Dominical Español Sábado Saturday Mass at 5:00pm Sunday Mass at 9:30am Reconciliation: 7:00pm fertilize it.” Domingo 8:00am y 12:00 Weekdays Mass: Sat. 4:30pm Medodía (Tue/Wed/Thu) 8:00am (E) Saturday Mass at 5:30pm Jueves 7:00pm Español Friday Mass at 7:00pm (V) Sunday Masses at 8:00am & Reconciliation / Con- Vietnamese Mass: 11:00am (Luke 13:9) fesiones Sunday Mass: 7:45 am Weekdays (Tue/Wed/Fri) Thursdays and Saturdays: Reconciliation: Sun. 3:00pm Mass at 9:30am from 6:00pm to 6:45pm Sunday Mass at 4:00pm Pastor’s Letter Dear Parishioners, We are in the Third Weekend of the Lenten journey with the Elects and Candidates. We thank you for continuing to support and pray for them during these Forty Days of their discernment towards the Baptismal Font and towards the Altar of the Eucha- ristic celebration! We thank their godparents and sponsors who are with them at each step of their journey. -

Tsr6903.Mu7.Ghotmu.C

[ Official Game Accessory Gamer's Handbook of the Volume 7 Contents Arcanna ................................3 Puck .............. ....................69 Cable ........... .... ....................5 Quantum ...............................71 Calypso .................................7 Rage ..................................73 Crimson and the Raven . ..................9 Red Wolf ...............................75 Crossbones ............................ 11 Rintrah .............. ..................77 Dane, Lorna ............. ...............13 Sefton, Amanda .........................79 Doctor Spectrum ........................15 Sersi ..................................81 Force ................................. 17 Set ................. ...................83 Gambit ................................21 Shadowmasters .... ... ..................85 Ghost Rider ............................23 Sif .................. ..................87 Great Lakes Avengers ....... .............25 Skinhead ...............................89 Guardians of the Galaxy . .................27 Solo ...................................91 Hodge, Cameron ........................33 Spider-Slayers .......... ................93 Kaluu ....... ............. ..............35 Stellaris ................................99 Kid Nova ................... ............37 Stygorr ...............................10 1 Knight and Fogg .........................39 Styx and Stone .........................10 3 Madame Web ...........................41 Sundragon ................... .........10 5 Marvel Boy .............................43 -

South Park - Winter 2019

Deerfield Park District After School Enrichments South Park - Winter 2019 Register online at register.deerfieldparks.org Registration opens Monday, November 26 at 9 am All Classes meet at South Park School. All students should meet in the multipurpose room for attendance. Please contact Mark Woolums at 847-572-2623 with any questions. WEEK AT A GLANCE Class Instructor Grade Art with Mari Mari Krasney K-5 Thunderbolts Flag Football Fit 4 Kids 1-4 Amazing Minds Amazing Minds K-2 Sticky Fingers Cooking Sticky Fingers Cooking K-5 Monday Class Instructor Grade Triple Play Hot Shot Sports K-3 Cartooning and More Susie Mason K-5 Cooking Taste Buds Kitchen 2-5 Little Footlighters Sarah Hall Theatre Company K-3 Yoga Movement Junkies K-5 Tuesday Class Instructor Grade Fit 4 Kids Fit 4 Kids K-3 Amazing Art Sunshine Crafts K-5 Guitar Sasha Brusin K-5 Spanish Fun Fluency 3-5 (Early) TechStars: Minecraft Mods & Sploder Computer Explorers 1-4 Wednesday Wednesday Cheerleading Soul 2 Soul Dance 3-5 Class Instructor Grade Lacrosse 5 Star Sports 1-4 TechStars: Game Design & Animation Computer Explorers 1-4 in 2D & 3D (Late) RubixFix Mr. Matthews 1-5 Wednesday Wednesday Spanish Fun Fluency 3-5 Class Instructor Grade Ceramics Richard Cohen K-5 Karate Focus Martial Arts K-5 Homework Club Mrs. Keidan 2-5 Sticky Fingers Cooking Sticky Fingers Cooking K-5 Pegasus FC Soccer Clinic Pegasus FC Soccer K-3 Thursday Class Instructor Grade Artopia Tiffany Shaf Plat K-5 Chess Chess Scholars K-5 Lil Dribblers Basketball Hot Shot Sports K-3 Friday Monday 1/14 - 3/18 | Time: 3:35 - 4:35 pm 7 Classes | No class 1/21, 2/18, 3/4 Art with Mari thunderbolts Amazing Activity # 251610-01 Flag Football Minds K-5 Grade | Fee: $120 Students will create multi-media Activity # 251610-02 Activity # 251610-03 projects, introducing them to a 1-4 Grade | Fee: $188 K-2 Grade | Fee: $157 variety of media including pencil, Thunderbolts: Join us this fall for Explore interesting topics and learn to watercolor, and acrylic. -

South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, the Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2009-01-01 South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Dungan, Drew W., "South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism" (2009). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 245. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/245 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan Department of Communication APPROVED: Richard D. Pineda, Ph.D., Chair Stacey Sowards, Ph.D. Robert L. Gunn, Ph.D. Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Drew W. Dungan 2009 Dedication To all who have been patient and kind, most of all Robert, Thalia, and Jesus, thank you for everything... South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies. The Art of Stealthy Conservatism by DREW W. DUNGAN, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2009 Abstract South Park serves as an example of satire and parody lampooning culture war issues in the popular media. -

PDF Download South Park Drawing Guide : Learn To

SOUTH PARK DRAWING GUIDE : LEARN TO DRAW KENNY, CARTMAN, KYLE, STAN, BUTTERS AND FRIENDS! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Go with the Flo Books | 100 pages | 04 Dec 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781519695369 | English | none South Park Drawing Guide : Learn to Draw Kenny, Cartman, Kyle, Stan, Butters and Friends! PDF Book Meanwhile, Butters is sent to a special camp where they "Pray the Gay Away. See more ideas about south park, south park anime, south park fanart. After a conversation with God, Kenny gets brought back to life and put on life support. This might be why there seems to be an air of detachment from Stan sometimes, either as a way to shake off hurt feelings or anger and frustration boiling from below the surface. I was asked if I could make Cartoon Animals. Whittle his Armor down and block his high-powered attacks and you'll bring him down, faster if you defeat Sparky, which lowers his defense more, which is recommended. Butters ends up Even Butters joins in when his T. Both will use their boss-specific skill on their first turn. Garrison wielding an ever-lively Mr. Collection: Merry Christmas. It is the main protagonists in South Park cartoon movie. Climb up the ladder and shoot the valve. Donovan tells them that he's in the backyard. He can later be found on the top ramp and still be aggressive, but cannot be battled. His best friend is Kyle Brovlovski. Privacy Policy.. To most people, South Park will forever remain one of the quirkiest and wittiest animated sitcoms created by two guys who can't draw well if their lives depended on it. -

PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues Through Satire

Colloquy Vol. 12, Fall 2016, pp. 101-114 PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues through Satire Alex Dejean Abstract This study takes an extensive look at the television program South Park episode “Stunning and Brave.” There is limited research that explores the use of satire to create social discourse on concepts related to political correctness. I use framing theory as a primary variable to understand the messages “Stunning and Brave” attempts to convey. Framing theory originated from the theory of agenda setting. Agenda setting explains how media depictions affect how people think about the world. Framing is an aspect of agenda setting that details the organization and structure of a narrative or story. Framing is such an important variable to agenda setting that research on framing has become its own field of study. Existing literature of framing theory, comedy, and television has shown how audiences perceive issues once they have been exposed to media messages. The purpose of this research will review relevant literature explored in this area to examine satirical criticism on the social issue of political correctness. It seems almost unnecessary to point out the effect media has on us every day. Media is a broad term for the collective entities and structures through which messages are created and transmitted to an audience. As noted by Semmel (1983), “Almost everyone agrees that the mass media shape the world around us” (p. 718). The media tells us what life is or what we need for a better life. We have been bombarded with messages about what is better. -

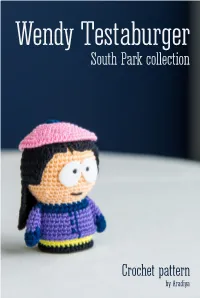

Eng Tutorial Wendy

Wendy Testaburger South Park collection Crochet pattern by Aradiya 1 Instruments and materials 1.25 and 2.00 mm hooks Purple, navy blue, pink, flesh-colored, yellow and black yarn Sewing needle Stung material A piece of white felt Image 1 Wendy Testaburger - character of the popular cartoon “South Park”. To create a toy with a height of 7.5 cm you must crochet with single yarn using a 2.00 mm hook. The arms, the hair and the hat are crocheted with single yarn using a 1.25 mm hook. The stung material used in this toy is polyester wadding. The piece of felt must be 1.5 mm thick. This pattern is for personal use only. Sharing information from this pattern is prohibited. If you publish photos of the toys that are crocheted following this pattern, it is better to mention the author of the pattern. You can also use hashtag #AradiyaToys at Twitter and Instagram to share your toy and see other toys that are created following AradiyaToys’ patterns. 2 Abbreviations Ch - chain Sl - slip stitch Sc - single crochet Dc - double crochet HDc - half double crochet INC - increase INVDEC - invisible decrease BLO - back loops only FLO - front loops only Tip 1 The toy must be All amigurumi toys crocheted with tight are crocheted with tight stitches. Avoid stitches, to be sure that small holes when there won't be any holes stretching crochet through which stung fabric, if there are material can some tiny holes, be seen. use a smaller size hook. To avoid seams, all details are crocheted in a spiral without slip stitch and lifting loops. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

ABSORBING MAN Villain

ABSORBING MAN Villain Real Name: Carl "Crusher" Creel Occupation: Professional criminal. Identity: Publicly known. Legal Status: Citizen of the United States with a criminal record. Other Aliases: None. Place of Birth: Houston, Texas. Marital Status: Presumably single. Known Relatives: None. Group Affiliation: None. Base of Operations: Mobile. First Post-Reboot Appearance: THOR: GOD OF THUNDER # History: Crusher Creel was a small-time criminal serving a prison sentence for aggravated assault when he was made an unwitting pawn in one of the schemes cooked up by the Norse trickster god, Loki (see Loki). Posing as one of the inmates assigned to work the prison cafeteria, Loki laced Creel's food with a rare Asgardian herb, granting him superhuman powers. Creel used these new powers to break out of prison, after which he was manipulated into combat with the Norse thunder god, Thor (see Thor). He has since clashed with the thunder god on a second occasion. It has recently come to light that the idea to transform Creel into the Absorbing Man was Sif's; Loki simply implemented it (see Sif). Height: 6' 4" Weight: 265 lbs. Eyes: Brown Hair: Bald; has brown facial hair. Uniform: None. Strength Level: Without changing his body, the Absorbing Man has the normal human strength of a man his age, height, and build who engages in intensive regular exercises. When using his powers, he can increase his strength to many times that, ultimately possessing the ability to lift (press) over 50 tons. Known Superhuman Powers: By touching an item, the Absorbing Man can take on its physical properties. -

Resistant Vulnerability in the Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 2-15-2019 1:00 PM Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America Kristen Allison The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Susan Knabe The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Kristen Allison 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Allison, Kristen, "Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6086. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6086 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Established in 2008 with the release of Iron Man, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has become a ubiquitous transmedia sensation. Its uniquely interwoven narrative provides auspicious grounds for scholarly consideration. The franchise conscientiously presents larger-than-life superheroes as complex and incredibly emotional individuals who form profound interpersonal relationships with one another. This thesis explores Sarah Hagelin’s concept of resistant vulnerability, which she defines as a “shared human experience,” as it manifests in the substantial relationships that Steve Rogers (Captain America) cultivates throughout the Captain America narrative (11). This project focuses on Steve’s relationships with the following characters: Agent Peggy Carter, Natasha Romanoff (Black Widow), and Bucky Barnes (The Winter Soldier).