Constructions of Gender in Dasam Granth Exegesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presently Published Dasam Granth and British Connection; Guru Granth Sahib As the Only Sikh Canon

Presently Published Dasam Granth and British Connection; Guru Granth Sahib as the only sikh canon (From www.GlobalSikhStudies.net) Jasbir Singh Mann M.D., California. The lineage of Personal Guruship was terminated ( Canon Closed) on October, 6th Wednesday1708 A.D. by the 10th Guru, Guru Gobind Singh Ji, after finalizing the sanctification of Guru Nanak’s Mission and passing the succession to Guru Granth Sahib as future Guru of the Sikhs. This was the final culmination of the Sikh concept of Guruship, capable of resisting the temptation of continuation of the lineage of human Gurus. The Tenth Guru while maintaining the concept of ‘Shabad Guru’ also made the Panth distinctive by introducing corporate Guruship. The concept of Guruship continued and the role of human gurus was transferred to the Guru Panth and that of the revealed word to Guru Granth Sahib making Sikhism a unique modern religion. This historical fact is well documented in Indian, Persian and Western Sikh sources of 18th century. Indian sources: Sainapat (1711), Bhai Nand Lal, Bhai Prahlad, and Chaupa Singh, Koer Singh (1751), Kesar Singh Chhibber (1769-1779Ad), Mehama Prakash (1776), Munshi Sant Singh ( on account of Bedi family of the Ulna, Unpublished records), Bhatt Vahi’s. Persian sources: Mirza Muhammad (1705-1719 AD), Sayad Muhammad Qasim (1722 AD), Hussain Lahauri(1731), Royal Court News of Mughals, Akhbarat-i-Darbar-i-Mualla (1708). Western sources: Father Wendel, Charles Wilkins, Crauford, James Browne, George Forester, and John Griffith. These sources clearly emphasize the tenets of Nanak as enshrined in Guru Granth Sahib as the only promulgated scripture of the Sikhs. -

Where Are the Women? the Representation of Gender in the Bhai Bala Janamsakhi Tradition and the Women's Oral Janamsakhi Tradition

WHERE ARE THE WOMEN? THE REPRESENTATION OF GENDER IN THE BHAI BALA JANAMSAKHI TRADITION AND THE WOMEN'S ORAL JANAMSAKHI TRADITION by Ranbir Kaur Johal B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1997 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Asian Studies) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2001 © Ranbir Kaur Johal, 2001 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Asia" SJ-ndUS The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) Abstract: The janamsakhis are a Sikh literary tradition, which consist of hagiographies concerning Guru Nanak's life and teachings. Although the janamsakhis are not reliable historical sources concerning the life of Guru Nanak, they are beneficial in imparting knowledge upon the time period in which they developed. The representation of women within these sakhis can give us an indication of the general views of women of the time. A lack of representation of women within the janamsakhi supports the argument that women have traditionally been assigned a subordinate role within patriarchal society. -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala (Established under Punjab Act No. 35 of 1961) Editor Dr. Shivani Thakar Asst. Professor (English) Department of Distance Education, Punjabi University, Patiala Laser Type Setting : Kakkar Computer, N.K. Road, Patiala Published by Dr. Manjit Singh Nijjar, Registrar, Punjabi University, Patiala and Printed at Kakkar Computer, Patiala :{Bhtof;Nh X[Bh nk;k wjbk ñ Ò uT[gd/ Ò ftfdnk thukoh sK goT[gekoh Ò iK gzu ok;h sK shoE tk;h Ò ñ Ò x[zxo{ tki? i/ wB[ bkr? Ò sT[ iw[ ejk eo/ w' f;T[ nkr? Ò ñ Ò ojkT[.. nk; fBok;h sT[ ;zfBnk;h Ò iK is[ i'rh sK ekfJnk G'rh Ò ò Ò dfJnk fdrzpo[ d/j phukoh Ò nkfg wo? ntok Bj wkoh Ò ó Ò J/e[ s{ j'fo t/; pj[s/o/.. BkBe[ ikD? u'i B s/o/ Ò ô Ò òõ Ò (;qh r[o{ rqzE ;kfjp, gzBk óôù) English Translation of University Dhuni True learning induces in the mind service of mankind. One subduing the five passions has truly taken abode at holy bathing-spots (1) The mind attuned to the infinite is the true singing of ankle-bells in ritual dances. With this how dare Yama intimidate me in the hereafter ? (Pause 1) One renouncing desire is the true Sanayasi. From continence comes true joy of living in the body (2) One contemplating to subdue the flesh is the truly Compassionate Jain ascetic. Such a one subduing the self, forbears harming others. (3) Thou Lord, art one and Sole. -

The Doctrinal Inconsistencies in Dasam Granth : in Relation to Avtarhood(Part I)

The Doctrinal inconsistencies in Dasam Granth : In relation to Avtarhood(Part I) Prof.Gurnam Kaur* (A) Introduction:- This paper is concerned with the authenticity of the compositions included in the Dasam Granth or we can say with the doctrinal inconsistencies in the Dasam Granth in relation to the idea of avtarhood,i.e. incarnation of God in different forms human or any, devi pooja (worship of goddess) shastar as Pir i.e. to worship weapons as the highest spiritual person, bias against unshorn hair, supporting the use of intoxicants and bias against woman. To judge all these things we have to take the help of Sikh tenants and adopt some basic criterion or methodology because these days animated discussions are going on about the Dasam Granth. The text has already been analyzed by known scholars from the historical, religious and theological points of view. Being the student of Sikh philosophy, with due regards to the analysis already done, I will try to analyze the text in the light of Sri Guru Granth Sahib. Sri Guru Granth Sahib is the basic and primary scripture of Sikh religion. No other scripture can be considered equal to it. This is the only Scripture in the history of the world religions which was compiled by its founder Gurus themselves. The fifth Guru Arjan Dev compiled the first recension and installed it at Harmander Sahib on Bhadon sudi. I, 1604 A.D. Bhai Gurdas was the first scribe and Baba Budha Ji was made the first Granthi. Guru Gobind Singh, the Tenth and last physical Guru, added the bani composed by Guru Teg Bahadur, the ninth Nanak Joti and bestowed 1 Guruship on the Granth before his final departure in samat 1765 from this mundane world. -

Dr Jaswant Singh Neki

The Stalwarts http://doi.org/10.18231/j.tjp.2019.034 Dr Jaswant Singh Neki Madhur Rathi Postgraduate, Dept. of Psychiatry, Institute of Mental Health, Osmania Medical College, Hyderabad, Telangana, India *Corresponding Author: Madhur Rathi Email: [email protected] Abstract Dr. Jaswant Singh Neki (1925–2015) is amongst the foremost psychiatrists of India. He has been variously described as a world-renowned mental health expert, a noted metaphysical poet, a teacher par excellence, and an excellent humane person of international repute. He joined his graduate course in medicine and surgery from King Edward Medical College, Lahore and completed graduation from Medical College, Amritsar.1 He passed his MA (Psychology) from Aligarh Muslim University. Later he passed DPM exam from All India Institute of Mental Health, Bangalore. He held high academic and administrative positions including Consultant - WHO, Geneva and UNDP S-E Asia. Keywords: J S Neki, Guru-Chela relationship, Kairos, Poet, Cross cultural psychotherapy. Introduction worked there for about a decade. Then he was appointed Dr Neki was born in village Murid, Distt. Jhelum (Pakistan), Director of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education on 27th August, 1925. His father, S. Hari Gulab Singh and and Research, Chandigarh. He spent next three years there. his mother, Smt. Sita Wanti were both God-fearing From there, he was picked up by the World Health individuals.1 When he was an infant, his parents shifted to Organization, Geneva, as a consultant for a project in Quetta (Baluchistan). He joined Khalsa High School in Africa. He served in Africa for over four years (1981- Quetta, from where he matriculated in 1941 securing the 1985)1. -

Reading Modern Punjabi Poetry: from Bhai Vir Singh to Surjit Patar

185 Tejwant S. Gill: Modern Punjabi Poetry Reading Modern Punjabi Poetry: From Bhai Vir Singh to Surjit Patar Tejwant Singh Gill Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar ________________________________________________ The paper evaluates the specificity of modern Punjabi poetry, along with its varied and multi-faceted readings by literary historians and critics. In terms of theme, form, style and technique, modern Punjabi poetry came upon the scene with the start of the twentieth century. Readings colored by historical sense, ideological concern and awareness of tradition have led to various types of reactions and interpretations. ________________________________________________________________ Our literary historians and critics generally agree that modern Punjabi poetry began with the advent of the twentieth century. The academic differences which they have do not come in the way of this common agreement. In contrast, earlier critics and historians, Mohan Singh Dewana the most academic of them all, take the modern in the sense of the new only. Such a criterion rests upon a passage of time that ushers in a new way of living. How this change then enters into poetic composition through theme, motif, technique, form, and style is not the concern of critics and historians who profess such a linear view of the modern. Mohan Singh Dewana, who was the first scholar to write the history of Punjabi literature, did not initially believe that something innovative came into being at the turn of the past century. If there was any change, it was not for the better. In his path-breaking History of Punjabi Literature (1932), he bemoaned that a sharp decline had taken place in Punjabi literature. -

THE EVOLUTION of the ROLE of WOMEN in the SIKH RELIGION Chapter Page

UGC MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT FILE NO: 23-515/08 SPIRITUAL WARRIORS: THE EVOLUTION OF THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN THE SIKH RELIGION SUBMITTED BY DR. MEENAKSHI RAJAN DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY S.K SOMAIYA COLLEGE OF ARTS, SCIENCE AND COMMERCE, VIDYAVIHAR, MUMBAI 400077 MARCH 2010 SPIRITUAL WARRIORS: THE EVOLUTION OF THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN THE SIKH RELIGION Chapter Page Number 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 ROLE OF WOMEN IN SIKH HISTORY 12 3 MATA TRIPTA 27 4 BIBI NANAKI 30 5 MATA KHIVI 36 6 BIBI BHANI 47 7 MATA SUNDARI 53 8 MAI BHAGO 57 9 SARDARNI SADA KAUR 65 10 CONCLUSION 69 BIBLIOGRAPHY 71 i Acknowledgement I acknowledge my obligation to the University Grants Commission for the financial assistance of this Minor Research Project on Spiritual Warriors: The Evolution of the Role of Women in the Sikh Religion. I extend my thanks to Principal K.Venkataramani and Prof. Parvathi Venkatesh for their constant encouragement. I am indebted to the college and library staff for their support. My endeavour could not have been realised without the love, support and encouragement from my husband, Mr.Murli Rajan and my daughter Radhika. I am grateful to my father, Dr. G.S Chauhan for sharing his deep knowledge of Sikhism and being my guiding light. ii 1 CHAPTER - 1 INTRODUCTION Sikhism is one of the youngest among world religions. It centers on the Guru –Sikh [teacher -disciple] relationship, which is considered to be sacred. The development of Sikhism is a remarkable story of a socio- religious movement which under the leadership of ten human Gurus’ developed into a well organized force in Punjab.1Conceived in northern India, this belief system preached and propagated values of universalism, liberalism, humanism and pluralism within the context of a “medieval age.” Its teachings were “revealed’ by Guru Nanak (1469-1539 AD) who was, in turn, succeeded by nine other Gurus’. -

1 UNIT 4 SIKHISM Contents 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2

UNIT 4 SIKHISM Contents 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Origin of Sikh Religion and Gurus 4.3 Sikh Scripture: Guru Granth Sahib 4.4 Teachings of Sikh Religion 4.5 Ethics of Sikhism 4.6 Sikh Institutions 4.7 Sikh Literature 4.8 Let Us Sum Up 4.9 Key Words 4.10 Further Readings and References 4.11 Answers to Check Your Progress 4.0 OBJECTIVES The main objective of this unit is to give an introduction to Sikhism. By the end of this Unit you are expected to understand: • the origin and development of Sikhism through the successive ten Gurus • the structural as well as conceptual framework of the Sikh Scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, and its cosmopolitan vision • the ethical aspects of Sikhism, ethical code of conduct, status of women and contributions of Sikh women to spirituality • the practical implications of Sikh teachings • the role of Sikh institutions • the Sikh ceremonies, rituals and festivals • the Sikh literature and Sikh socio-religious movements 4.1 INTRODUCTION In the history of Punjab, Guru Nanak appeared at a time when there was complete disintegration not only social and political but also moral and spiritual. Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikh religion, has presented a microscopic portrayal of society in his compositions. He was totally aware of his surrounding atmosphere, religious as well as non-religious. He condemns the external paraphernalia of religion with all its religious rites, ceremonies, sacrifices, pilgrimages, idol-worship and ascetic practices which enhance human’s ego and deprive one of highest spiritual truths. He denounces the empty religious rituals and reacted strongly against the formal ways of worship of orthodox priestly class of Islam and Hinduism. -

Sikh Women's Life Writing in the Diaspora

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons Journal Articles FacWorks 10-2019 Negotiating Ambivalent Gender Space for Collective and Individual Empowerment: Sikh Women's Life Writing in the Diaspora Jaspal Kaur Singh 2508334 Northern Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/facwork_journalarticles Part of the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Singh, Jaspal K. "Negotiating Ambivalent Gender Spaces for Collective and Individual Empowerment: Sikh Women’s Life Writing in the Diaspora." Religions, vol. 10, no. 11, 2019, pp. 598. This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the FacWorks at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. religions Article Negotiating Ambivalent Gender Spaces for Collective and Individual Empowerment: Sikh Women’s Life Writing in the Diaspora Jaspal Kaur Singh Department of English, Northern Michigan University, Marquette, MI 49855-5301, USA; [email protected] Received: 18 May 2019; Accepted: 17 October 2019; Published: 28 October 2019 Abstract: In order to examine gender and identity within Sikh literature and culture and to understand the construction of gender and the practice of Sikhi within the contemporary Sikh diaspora in the US, I analyze a selection from creative non-fiction pieces, variously termed essays, personal narrative, or life writing, in Meeta Kaur’s edited collection, Her Name is Kaur: Sikh American Women Write About Love, Courage, and Faith. -

Saffron Cloud

WAY OF THE SAFFRON CLOUD MYSTERY OF THE NAM-JAP TRANSCENDENTAL MEDITATION THE SIKH WAY A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO CONCENTRATION Dr. KULWANT SINGH PUBLISHED AS A SPECIAL EDITION OF GURBANI ISS JAGG MEH CHANAN, TO HONOR 300TH BIRTHDAY OF THE KHALSA, IN 1999. WAY OF THE SAFFRON CLOUD Electronic Version, for Gurbani-CD, authored by Dr. Kulbir Singh Thind, 3724 Hascienda Street, San Mateo, California 94403, USA. The number of this Gurbani- CD, dedicated to the sevice of the Panth, is expected to reach 25,000 by the 300th birthday of the Khalsa, on Baisakhi day of 1999. saffron.doc, MS Window 95, MS Word 97. 18th July 1998, Saturday, First Birthday of Sartaj Singh Khokhar. Way of the Saffron Cloud. This book reveals in detail the mystery of the Name of God. It is a spiritual treatise for the uplift of the humanity and is the practical help-book (Guide) to achieve concentration on the Naam-Jaap (Recitation of His Name) with particular stress on the Sikh-Way of doing it. It will be easy to understand if labeled "Transcendental Meditation the Sikh -Way," though meditation is an entirely different procedure. Main purpose of this book is to train the aspirant from any faith, to acquire the ability to apply his -her own mind independently, to devise the personalized techniques to focus it on the Lord. Information about the Book - Rights of this Book. All rights are reserved by the author Dr. Kulwant Singh Khokhar, 12502 Nightingale Drive, Chester, Virginia 23836, USA. Phone – mostly (804)530-0160, and sometimes (804)530-5117. -

Reconstructing Gender Identities from Sikh Literature (1500-1920)

RECONSTRUCTING GENDER IDENTITIES FROM SIKH LITERATURE (1500-1920) A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SUPERVISOR SUBMITTED BY : DR. SULAKHAN SINGH PARMAR NIRAPJIT Professor Research Scholar Department of History Department of History Guru Nanak Dev University Guru Nanak Dev University Amritsar Amritsar DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY GURU NANAK DEV UNIVERSITY AMRITSAR 2010 CERTIFICATE It is certified that the thesis entitled Reconstructing Gender Identities from Sikh Literature (1500-1920) , being submitted by Parmar Nirapjit in fulfillment for the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, is a record of candidate’s own work carried out by her under my supervision and guidance. The matter embodied in the thesis has not been submitted earlier for the award of any other degree. Date : Dr. Sulakhan Singh Professor CERTIFICATE It is certified that the thesis entitled Reconstructing Gender Identities from Sikh Literature (1500-1920) , is entirely my own work and all the ideas and references have been duly acknowledged. Dr. Sulakhan Singh Parmar Nirapjit Professor Department of History Guru Nanak Dev University Amritsar PREFACE Women’s issues have always created a deep urge in me to prod deeper into their problems and the manner in which these problems are faced by them. Women since ages are addressed as the weaker sex and it becomes ironical that apart from a section of the male population, majority of the women themselves support this view. In building gender attitudes of people religions play a major role. -

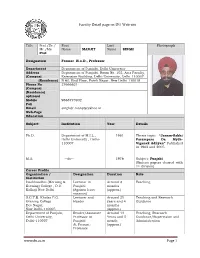

Faculty Detail Page on DU Web-Site

Faculty Detail page on DU Web-site Title Prof./Dr./ First Last Photograph Mr./Ms Name MANJIT Name SINGH Prof. Designation Former H.o.D., Professor Department Department of Punjabi, Delhi University Address Department of Punjabi, Room No. 102, Arts Faculty, (Campus) Extension Building, Delhi University, Delhi-110007 (Residence) B-60, IInd Floor, Fateh Nagar, New Delhi-110018 Phone No 27666621 (Campus) (Residence) optional Mobile 9868773902 Fax Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. Department of M.I.L., 1981 Thesis topic: “Janam-Sakhi Delhi University , Delhi- Parampara Da Myth- 110007 Viganak Adhyan” Published in 1982 and 2005. M.A. --do-- 1976 Subject: Punjabi (Sixteen papers cleared with 1st division) Career Profile Organization / Designation Duration Role Institution Deshbandhu (Morning & Lecturer in Around 2 Teaching Evening) College , D.U. Punjabi months Kalkaji New Delhi (Against leave (approx.) vacancy) S.G.T.B. Khalsa P.G. Lecturer and Around 25 Teaching and Research Evening College Reader years and 4 Guidance Dev Nagar, months New Delhi-110005 (approx.) Department of Punjabi, Reader/Associate Around 13 Teaching, Research Delhi University, Professor in Years and 5 Guidance/Supervision and Delhi-110007 Punjabi month Administration At Present: (approx.) Professor www.du.ac.in Page 1 Research Interests / Specialization Mythology & The Science of Myth and Gurmat Poetry Folkloristics, Cross-disciplinary Semiotics Western Poetics and Culturology, Medieval and Modern Punjabi Literature. Research Supervision A. Supervision of awarded Doctoral Theses ______________________________________________________________________________ S.No. Title of the Thesis Year of Present Name of the Scholar Submission Position 1 “San 1850 ton 1900 tak Di 1995 Approved Ms.