Reading the 'Foreign Skull': an Episode in Nineteenth-Century Colonial Human Dissection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF File Created from a TIFF Image by Tiff2pdf

~. ~. ~••r __._ .,'__, __----., The National Ubrary supplies copies of this article under licence from the Copyright Agency Limited (GAL). Further reproductions of this' article can only be made under licence. ·111111111111 200003177 . J The Last Man: The mutilation ofWilliam Lanne in 1869 and its aftermath Stefan Petrow Regarding the story of King Billy's Head, there are so many versions of it that it might be as well if you sent rhe correct details.! In 1869 William Lanne, the last 'full-blooded' Tasmanian Aboriginal male, died.2 Lying in the Hobart Town General Hospital, his dead body was mutilated by scientists com peting for the right to secure the skeleton. The first mutilation by Dr. William Lodewyk Crowther removed Lanne's head. The second mutilation by Dr. George Stokell and oth ers removed Lanne's hands and feet. After Lanne's burial, Stokell and his colleagues removed Lanne's body from his grave before Crowther and his party could do the same. Lanne's skull and body were never reunited. They were guarded jealously by the respective mutilators in the interests of science. By donating Lanne's skeleton, Crowther wanted to curry favour with the prestigious Royal College of Surgeons in London, while Stokell, anxious to retain his position as house-surgeon at the general hospital, wanted to cultivate good relations with the powerful men associated with the Royal Society of Tasmania. But, perhaps because of the scandal associated with the mutilation, no scientific study of Lanne's skull or skeleton was ever published or, as far as we know, even attempted. -

The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence 1860-1941

The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence 1860-1941 Andrew Kilsby A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences February 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the rifle club movement and its relationship with Australian defence to 1941. It looks at the origins and evolution of the rifle clubs and associations within the context of defence developments. It analyses their leadership, structure, levels of Government and Defence support, motivations and activities, focusing on the peak bodies. The primary question addressed is: why the rifle club movement, despite its strong association with military rifle shooting, failed to realise its potential as an active military reserve, leading it to be by-passed by the military as an effective force in two world wars? In the 19th century, what became known as the rifle club movement evolved alongside defence developments in the Australian colonies. Rifle associations were formed to support the Volunteers and later Militia forces, with the first ‘national’ rifle association formed in 1888. Defence authorities came to see rifle clubs, especially the popular civilian rifle clubs, as a cheap defence asset, and demanded more control in return for ammunition grants, free rail travel and use of rifle ranges. At the same time, civilian rifle clubs grew in influence within their associations and their members resisted military control. An essential contradiction developed. The military wanted rifle clubs to conduct shooting ‘under service conditions’, which included drill; the rifle clubs preferred their traditional target shooting for money prizes. -

The Influence of India on Colonial Tasmanian Architecture and Artefacts

The influence of India on colonial Tasmanian architecture and artefacts Lionel Morrell Background India has a long history of connections with Australia. Long before Captain Cook set foot on southern shores, cloth from ‘the Indies’ had traded its way from Gujarat and Coromandel down through the Indonesian archipelago to be traded with Aborigines by Makassar seamen negotiating seasonal camps to collect trepang, fish and pearl. According to Sharrad in Convicts, Call Centres and Cochin Kangaroos 1 it was men like Mitchell and Lang, from the 1820s on, who retired to land grants in Van Diemen’s Land and later other parts of Australia, who brought with them the verandahs of the Raj that became part of Australian architecture, and familiarity with India. As early as 1824, an attempt was made to found an institution for the sons of Anglo- Indians and British men in Van Diemen’s Land. Following the Indian mutiny of 1857, there was a rise in the numbers of Anglo-Indians settling in Australia, There were 372 Indian-born registered in 1881 2. Among them was Dr John Coverdale, born in 1814 in Kedgeree, Bengal, who was a medical practitioner at Richmond for many years. The term ‘Anglo-Indian’ was first used by Warren Hastings in the eighteenth century to describe both the British in India and their Indian-born children. 3 The first Anglo-Indian to settle in Tasmania was Rowland Walpole Loane in 1809, followed by many others, including Edward Dumaresq, a retired Indian Army officer who bought Mt Ireh in 1855 and lived there until his death in 1906 at the age of 104; Charles Swanston, who first came to VDL in 1828 on leave because of ill-health from his position as military paymaster in the provinces of Tranvancore and Tinnevelly in India and eventually settled here permanently in 1831 and Michael Fenton, who joined the 13 th Light Infantry in 1807 and served in India and Burma until 1828 when he sold his commission and emigrated to Van Diemen’s Land. -

Aboriginal History Journal: Volume 21

Aboriginal History Volume twenty-one 1997 Aboriginal History Incorporated The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Secretary), Peter Grimshaw (Treasurer/Public Officer), Neil Andrews, Richard Baker, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Luise Hercus, Bill Humes, Ian Keen, David Johnston, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Diane Smith, Elspeth Young. Correspondents Jeremy Beckett, Valerie Chapman, Ian Clark, Eve Fesl, Fay Gale, Ronald Lampert, Campbell Macknight, Ewan Morris, John Mulvaney, Andrew Markus, Bob Reece, Henry Reynolds, Shirley Roser, Lyndall Ryan, Bruce Shaw, Tom Stannage, Robert Tonkinson, James Urry. Aboriginal History aims to present articles and information in the field of Australian ethnohistory, particularly in the post-contact history of the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia will be welcomed. Issues include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, resumes of current events, archival and bibliographical articles, and book reviews. Editors 1997 Rob Paton and Di Smith, Editors, Luise Hercus, Review Editor and Ian Howie Willis, Managing Editor. Aboriginal History Monograph Series Published occasionally, the monographs present longer discussions or a series of articles on single subjects of contemporary interest. Previous monograph titles are D. Barwick, M. Mace and T. Stannage (eds), Handbook of Aboriginal and Islander History; Diane Bell and Pam Ditton, Law: the old the nexo; Peter Sutton, Country: Aboriginal boundaries and land ownership in Australia; Link-Up (NSW) and Tikka Wilson, In the Best Interest of the Child? Stolen children: Aboriginal pain/white shame, Jane Simpson and Luise Hercus, History in Portraits: biographies of nineteenth century South Australian Aboriginal people. -

Brothers Under Arms, the Tasmanian Volunteers

[An earlier version was presented to Linford Lodge of Research. The improved version, below, was to have been presented to the Discovery Lodge of Research on 6 September 2012, but, owing to illness of the author, was simply published in the Transactions of Discovery Lodge in October 2012.] Brothers under Arms, the Tasmanian Volunteers by Bro Tony Pope Introduction For most of my life, as a newspaper reporter, police officer, and Masonic researcher, I have been guided by the advice of that sage old journalist, Bro Rudyard Kipling:1 I keep six honest serving men (They taught me all I knew); Their names are What and Why and When And How and Where and Who. But this paper is experimental, in that I have also taken heed of the suggestions of three other brethren: Bro Richard Dawes, who asked the speakers at the Goulburn seminar last year to preface their talks with an account of how they set about researching and preparing their papers; Bro Bob James, who urges us to broaden the scope of our research, to present Freemasonry within its social context, and to emulate Socrates rather than Moses in our presentation; and Bro Trevor Stewart, whose advice is contained in the paper published in the July Transactions, ‘The curious case of Brother Gustav Petrie’. Tasmania 1995 Rudyard Kipling Richard Dawes Bob James Trevor Stewart I confess that I have not the slightest idea how to employ the Socratic method in covering my chosen subject, and I have not strained my brain to formulate Bro Stewart’s ‘third order or philosophical’ questions, but within those limitations this paper is offered as an honest attempt to incorporate the advice of these brethren. -

L'ton Thematic History Report

LAUNCESTON HERITAGE STUDY STAGE 1: THEMATIC HISTORY Prepared by Ian Terry & Nathalie Servant for Launceston City Council July 2002 © Launceston City Council Cover. Launceston in the mid nineteenth century (Sarah Ann Fogg, Launceston: Tamar Street Bridge area , Allport Library & Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania). C O N T E N T S The Study Area ........................................................................................................................1 The Study .................................................................................................................................2 Authorship................................................................................................................................2 Methodology ............................................................................................................................2 Acknowledgments....................................................................................................................3 Abbreviations ...........................................................................................................................3 HISTORIC CONTEXT Introduction..............................................................................................................................4 1 Environmental Context .........................................................................................................5 2 Human Settlement.................................................................................................................6 -

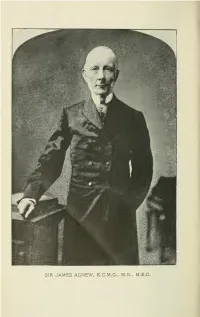

SIR JAMES AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.G. ©Bititarn*

SIR JAMES AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.G. ©bititarn* Sir James Wilson Agnew, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.C., Senior Vice-President of the Royal Society of Tas- mania. Died on cSth November, 1901, in the 87th year of his age. —Born at Ballyclare, Ireland, on the 2nd October, 1815, he studied for the medical profession in London and Paris, and at Glas^^-ow, where he graduated M.D., as his father and grandfather had done before him, and came to Australia in 1839. After a short stay in New South Wales and Victoria (then known as Port Phillip), he accepted from Sir John Franklin the offer of appointment as medical officer to an important station at Tasman's Peninsula, wliere he devoted the greater part of his leisure time to the study of natural history. Prior to his removal to Hobart for the more extended practice of his profession, in which he sub- sequently attained a position of acknowledged eminence, he had assisted in founding the Tasmanian Societ}^, and lie became an active member of the Royal Society, into which the former Society merged in 1844. Shortly after the retirement of Dr. Milligan, its Secretary and Curator, in 1860, he undertook the duties of Seci'etary as a labour of love, in order that the whole of the limited amount available out of income might be appropriated as salary for the Curator of the Museum. From that time on- wards, except during occasional periods of absence from Tasmania, he continued to act as chief executive officer of the Royal Society in the capacity of Honorary Secretary for many years, and latterly in that of Chairman of the Council ; and to the admirable manner in which those self-imposed duties were discharo-ed. -

Development of Tasmanian Water Right Legislation 1877-1885: a Tortuous Process

Journal of Australasian Mining History, Vol. 15, 2017 Development of Tasmanian water right legislation 1877-1885: a tortuous process By KEITH PRESTON rior to the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s, a right to water was governed by the riparian doctrine, a common law principle of entitlement that was established P in Great Britain during the 15th and 16th centuries.1 Water entitlements were tied to land ownership whereby the occupant could access a watercourse flowing through a landholding or along its boundary. This doctrine was introduced to New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land in 1828 with the passing of the Australian Courts Act (9 Geo. No. 4) that transferred ‘all laws and statutes in force in the realm of England’.2 The riparian doctrine became part of New South Wales common law following a Supreme Court ruling in 1859.3 During the Californian and Victorian gold rushes, the principle of prior appropriation was established to protect the rights of mining leaseholders on crown land but riparian rights were retained for other users, particularly for irrigation of private land. The principle of prior appropriation was based on first possession, which established priority when later users obtained water from a common source, although these rights could be traded and were a valuable asset in the regulation of water supply to competing claims on mining fields.4 In Tasmania, disputes over water rights between 1881-85 challenged the application of these two doctrines, forcing repeated revision of legislation. The Tasmanian Parliament passed the first gold mining legislation in September 1859, eight years after the first gold rushes in Victoria and New South Wales, which marked the widespread introduction of alluvial mining in Australia. -

Intercolonial Exhibition Report of Tasmanian Commissioners

(No. 66.) l 8 6 7. TASMANIA. LEGISLATIVE CO UN GIL. INTER COLONIAL EXHIBITION. REPORT OF THE TASMANIAN COMMISSIONERS. Laid upon the Table by. Sir R. Dry, and ordered by the Council to be printed, · October l 0, J 867. By His Excellency Colonel THOMAS GoRE BROWNE, Companion of the Most Honorable Order oftlte Bath, Capta,in-General and Governor-in Chief of Tasmania and its Dependencies. To the Honorable EDWARD ABBOTT, Esquire, M.L.C., JAMES WILSON AGNEW, Esquire, M.D., MORTON ALLPORT, Esquire, ABRAHAM BARRETT, Esquire, HENRY BUTLER, Esquire, M,H.A., EDWARD LEWIS DITCHAM, Esquire, ADYE DouGLAs, Esquire, M.H.A., · Mayor of Launceston, the Hunorable Sir RICHARD DRY, Knight, M.L.C., CHARLES GouLD, Esquire, RONALD CAMPBELL GUNN, Esquire, the Honorable . ALFRED KENNERLEY, Esquire, M.L.C., the lionorable ALEXANDER K1ssocK, Esquire, M.L.C., DAVID LEWIS, Esquire, M.H.A., THOMAS MACDOWELL, Esquire, the Honorable RoBERT OFFICER, Esquire, M.H,A, JAM~S RoirnRTSON, Esquire, JAMES SCOTT, Esquire, and RoBERT WALKER, Esquire, M.H.A., Mayor of Hobart Town. GREETING: WHEREAS it is expedient that a Commission be appointed for the purpose of making and carry ing out all necessary arrangements to enable the Colony of Tasmania to take due part in aid of the Inter-Colonial Exhibition to be held in Melbourne, _in tlie Colony of Victoria, during the current year: Know ye that I, reposing great trust and confidence in your fidelity, discretion, and integrity, have authorised and appointed, and do by these Presents authorise and appoint, you, or any three or more -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

Clonal Sncittn oi Casmanhi. ABSTRACT OF PHOCEELINaS, APPwIL 29th, 1902. A meeting of the Eoyal Socie!;y of Tas- and expansive beyond any limit they mania was held on Tuesday evening, April could assign to it.'" The Fellows had 29, 1902, in the society^s new room, Argyle- done very well so far. They had got s'treet. The President, His Excellency natural history specimens, and a fairly the GrOTernor, Sir Arthur Havelook, good rep.resantation of art, and, on tlie G.C.S.I., G.'C.M.G., presided. The Go- whole, he thought the institution would vernor was accompanied by Lady Have- compare favourably with any institution lock and Captain Gaskell, A.D.C. in the other States. But they could say now. as the secretary said in 18o7, that the Welcome to the New President. society must be cumulative and expan- sive beyond any limit thsy could a».-ign The Hon. Nicholas J. Brown, Speaker to it. Its first expansion now should be of the House of Assembly, and Vice-Presi- in the direction of the securing and equip- dent of the Eoyal Society, said he was ment of a Techuological museum. I'hat charged with a duty of a y&i:y pleasant seemed to be necessary, in view of the an- character. He had, on behalf of the ticipations that, in the near fature, Tas- Fellows of the Eoyal Society, to welcome mania would become an important manu- His Excellency on that, the first, occasion facturing and distributing centre for the of fTiS presiding at a meeting of the Eel- whole of Australia. -

Melbourne Club Address 12Th Aug 09

J Michael M Youl The success of his experiment may have been the TASMANIAN Club address 6 July 2012 fore runner to storing animal and human semen and storing animal and human fertile eggs, IVF and so Good evening Gentlemen on [now I’m really out of my depth]. In the 1850’s and 60’s there was a strong desire by Packaging took a great deal of sorting out. James colonist in Tasmania and Victoria to introduce Youl spent 10 years to find the right mix. His Atlantic salmon [ salmo salar ] to our beautiful experiments to retard hatching were carried out at clean and clear rivers the Crystal Palace, London, using ice from the Wenham Ice Co. Boston USA. The first attempt to transport Salmon ova was by Gottlieb Boccius in 1852 aboard the “Columbus”. The Tasmanian Government announced a reward of Wooden Troughs holding 60 gallons of water were 500 pounds in 1857 for the introduction of live slung gimbal style amid-ship, hoping the little ova Atlantic salmon [not live ova]. That was little would handle the sea trip. The experiment failed the support for JAY. water temperature was not controlled plus the ova Edward Wilson who was a part-owner and editor of had no protection The Argus newspaper in Melbourne, and also founded the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria As James Youl is prominent in my address tonight persuaded the Society to offer 600 pounds to his I’ll provide his back ground. good friend James Youl to organize and manage a He was born Dec. -

Tasmania's Neglected Children, Their Parents and State Care, 1890-1918

PROTECTING THE INNOCENT: TASMANIA'S NEGLECTED CHILDREN, THEIR PARENTS AND STATE CARE, 1890-1918 CAROLINE EVANS BA (HONS) Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Tasmania, June 1999. AUTHORITY OF ACCESS This thesis may be available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any tertiary institution. To the best of the candidate's knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis. For my daughters, Freya and Leah Sant and my mother, Cleone Evans CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgments Map Notes on the Text Introduction 1 Part One: Reformers, Public Servants and Changing Concepts of Neglect in Childhood 1. The Neglected Child 17 2. "Poor wand'rers": Street Children and Welfare Reform 32 Liberal and Evangelical Influences on Child Welfare Policy 34 Challenges to and Support for Liberal Social Visions 42 The Introduction of Child Welfare Legislation, 1895-6 48 Street Children after 1896 56 Truancy 61 3. "The infant's wail": Children's Physical Efficiency and Welfare Reform 64 Child Welfare Reformers and National Efficiency 69 The Causes of Ex-Nuptial Infant Deaths 74 The 1907 Infant Life Protection Act 77 A "better provision for the protection of infant life"? 83 The Effects of World War I on Policy 87 "The most valuable department of the government": The Administration of the Neglected Children's Department 90 F.R.