Scots Pine (Pinus Sylvestris)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimating Numbers of Embryonic Lethals in Conifers

Heredity 69(1992)308—314 Received 26 November 1991 OThe Genetical Society of Great Britain Estimating numbers of embryonic lethals in conifers OUTI SAVOLAINEN, KATRI KARKKAINEN & HELMI KUITTINEN* Department of Genetics, University of Oulu, Oulu, Fin/and and *Department of Genetics, University of Helsinki, He/sink,, Fin/and Conifershave recessive lethal genes that eliminate most selfed embryos during seed development. It has been estimated that Scots pine has, on average, nine recessive lethals which act during seed development. Such high numbers are not consistent with the level of outcrossing, about 0.9—0.95, which has been observed in natural populations. Correcting for environmental mortality or using partial selfings provides significantly lower estimates of lethals. A similar discordance with numbers of lethals and observed outcrossing rates is true for other species. Keywords:embryoniclethals, inbreeding depression, outcrossing, Pinus sylvestris, Picea omorika. Introduction Reproduction system of conifers Conifershave no self-incompatibility mechanisms but Theproportion of self-pollination in conifers is early-acting inbreeding depression eliminates selfed variable. Sarvas (1962) suggested an average of 26 per embryos before seed maturation (Sarvas, 1962; cent for Pinus sylvestris, while Koski (1970) estimated Hagman & Mikkola, 1963). A genetic model for this values of self-fertilization around 10 per cent. The inbreeding depression has been developed by Koski genera Pinus and Picea have polyzygotic poly- (1971) and Bramlett & Popham (1971). Koski (1971, embryony, i.e. the ovules contain several archegonia. In 1973) has estimated that Pinus sylvestris and Picea Pinus sylvestris, the most common number of arche- abies have on average nine and 10 recessive lethals, gonia is two but it can range from one to five. -

SILVER BIRCH (BETULA PENDULA) at 200-230°C Raimo Alkn Risto Kotilainen

THERMAL BEHAVIOR OF SCOTS PINE (PINUS SYLVESTRIS) AND SILVER BIRCH (BETULA PENDULA) AT 200-230°C Postgraduate Student Raimo Alkn Professor and Risto Kotilainen Postgraduate Student Department of Chemistry, Laboratory of Applied Chemistry University of Jyvaskyla, PO. Box 35, FIN-40351 Jyvaskyla, Finland (Received April 1998) ABSTRACT Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and silver birch (Betuln pendula) were heated for 4-8 h in a steam atmosphere at low temperatures (200-230°C). The birch feedstock decomposed slightly more exten- sively (6.4-10.2 and 13515.2% of the initial DS at 200°C and 225"C, respectively) than the pine feedstock (5.7-7.0 and 11.1-15.2% at 205°C and 230°C. respectively). The results indicated that the differences in mass loss between these feedstocks were due to mainly the fact that carbohydrates (cellulose and hemicelluloses) were more amenable to various degradation reactions than lignin in intact wood. The degradation reactions were also monitored in both cases by determining changes in the elemental composition of the heat-treated products. Keywords: Heat treatment, carbohydrates, lignin, extractives, Pinus sylvestris, Betula pendula. INTRODUCTION content of hemicelluloses (25-30% of DS) In our previous experiments (AlCn et al. than hardwood (lignin and hemicelluloses are 2000), the thermal degradation of the structur- usually in the range 20-25 and 30-35% of al constituents (lignin and polysaccharides, DS, respectively). On the basis of these facts, i.e., cellulose and hemicelluloses) of Norway the thermal behavior of softwood and hard- spruce (Picea abies) was established under wood can be expected to be different, even at conditions (temperature range 180-225"C, low temperatures. -

Examensarbete I Ämnet Biologi

Examensarbete 2012:10 i ämnet biologi Comparison of bird communities in stands of introduced lodgepole pine and native Scots pine in Sweden Arvid Alm Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Fakulteten för skogsvetenskap Institutionen för vilt, fisk och miljö Examensarbete i biologi, 15 hp, G2E Umeå 2012 Examensarbete 2012:10 i ämnet biologi Comparison of bird communities in stands of introduced lodgepole pine and native Scots pine in Sweden Jämförelse mellan fågelsamhällen i bestånd av introducerad contortatall och inhemsk tall i Sverige Arvid Alm Keywords: Boreal forest, Pinus contorta, Pinus sylvestris, bird assemblage, Muscicapa striata Handledare: Jean-Michel Roberge & Adriaan de Jong 15 hp, G2E Examinator: Lars Edenius Kurskod EX0571 SLU, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Fakulteten för skogsvetenskap Faculty of Forestry Institutionen för vilt, fisk och miljö Dept. of Wildlife, Fish, and Environmental Studies Umeå 2012 Abstract The introduced lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) occupies more than 650 000 hectares in Sweden. There are some differences between lodgepole pine and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) forests which could affect bird assemblages, for example differences in canopy density and ground vegetation. Birds were surveyed in 14 localities in northern Sweden, each characterized by one middle-aged stand of lodgepole pine next to a stand of Scots pine. The two paired stands in each locality were planted by the forestry company SCA at the same time and in similar environment to evaluate the potential of lodgepole pine in Sweden. In those 14 localities, one to three point count stations were established in both the lodgepole pine and the Scots pine stand, depending on the size of the area. -

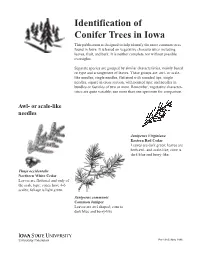

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

Pinus Resinosa Common Name: Red Pine Family Name: Pinaceae –

Plant Profiles: HORT 2242 Landscape Plants II Botanical Name: Pinus resinosa Common Name: red pine Family Name: Pinaceae – pine family General Description: Pinus resinosa is a rugged pine capable of withstanding extremes in heat and cold. Native to North America, the Chicago region is on the southern edge of its range where it is reported only in Lake and LaSalle counties. Red pine does best on dry, sandy, infertile soils. Although red pine has ornamental features, it is not often used in the landscape. There are a few unique cultivars that may be of use in specialty gardens or landscapes. Zone: 2-5 Resources Consulted: Dirr, Michael A. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants: Their Identification, Ornamental Characteristics, Culture, Propagation and Uses. Champaign: Stipes, 2009. Print. "The PLANTS Database." USDA, NRCS. National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA, 2014. Web. 21 Jan. 2014. Swink, Floyd, and Gerould Wilhelm. Plants of the Chicago Region. Indianapolis: Indiana Academy of Science, 1994. Print. Creator: Julia Fitzpatrick-Cooper, Professor, College of DuPage Creation Date: 2014 Keywords/Tags: Pinaceae, tree, conifer, cone, needle, evergreen, Pinus resinosa, red pine Whole plant/Habit: Description: When young, Pinus resinosa has the typical pyramidal shape of most pines. When open grown, as in this image, the branches develop lower on the trunk creating a dense crown. Notice the foliage is concentrated in dense tufts at the tips of the branches. This is characteristic of red pine. Image Source: Karren Wcisel, TreeTopics.com Image Date: September 27, 2010 Image File Name: red_pine_2104.png Whole plant/Habit: Description: Pinus resinosa is often planted in groves to serve as a windbreak. -

Apparent Hybridisation of Firecrest and Goldcrest F

Apparent hybridisation of Firecrest and Goldcrest F. K. Cobb From 20th to 29th June 1974, a male Firecrest Regulus ignicapillus was seen regularly, singing strongly but evidently without a mate, in a wood in east Suffolk. The area had not been visited for some time before 20th June, so that it is not known how long he had been present. The wood covers some 10 ha and is mainly deciduous, com prised of oaks Quercus robur, sycamores Acer pseudoplatanus, and silver birches Betula pendula; there is also, however, a scatter of European larches Larix decidua and Scots pines Pinus sylvestris, with an occasional Norway spruce Picea abies. Apart from the silver birches, most are mature trees. The Firecrest sang usually from any one of about a dozen Scots pines scattered over half to three-quarters of a hectare. There was also a single Norway spruce some 18-20 metres high in this area, which was sometimes used as a song post, but the bird showed no preference for it over the Scots pines. He fed mainly in the surround ing deciduous trees, but was never heard to sing from them. The possibility of an incubating female was considered, but, as the male showed no preference for any particular tree, this was thought unlikely. Then, on 30th June, G. J. Jobson saw the Firecrest with another Regulus in the Norway spruce and, later that day, D. J. Pearson and J. G. Rolfe watched this second bird carrying a feather in the same tree. No one obtained good views of it, but, not unnaturally, all assumed that it was a female Firecrest. -

Selection and Care of Your Christmas Tree

Selection and Care of Your Christmas Tree People seldom realize that a Christmas tree is not a timber tree whose aspirations have been frustrated by an untimely demise. It is realizing its appointed destiny as a living room centerpiece symbolic of "man's mystic union with nature." Moreover, while it grows, it provides cover for a variety of wildlife, enhances rural beauty, contributes to the local economy and helps to purify the atmosphere by absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. A large selection of Christmas trees is available to New York residents. Most of the trees are grown in plantations, but some still come from natural forest areas. Only the few species of trees that are commercially significant will be discussed in this bulletin. Selecting a Tree One of the joys of the Yule season can be selecting and cutting a tree. Many Christmas tree growers in New York State are willing to let the purchaser do so himself. Also, Christmas tree growers usually have a good selection of freshly cut trees at roadside stands. Such facilities assure you of fresh trees rather than trees that were cut some time ago and shipped long distances. "Freshness," however, relates to a tree's moisture content. With favorable storage and atmospheric conditions, a tree can still contain adequate moisture many weeks after harvest. Some growers control moisture loss from their products by applying a plastic anti-transpirant spray to the growing trees just prior to harvest. In New York, Christmas trees can be divided into two main groups: the short-needled spruces and firs and the long- needled pines. -

Structure, Development, and Spatial Patterns in Pinus Resinosa Forests of Northern Minnesota, U.S.A

Structure, development, and spatial patterns in Pinus resinosa forests of northern Minnesota, U.S.A. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Emily Jane Silver IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE Anthony W. D’Amato Shawn Fraver July 2012 © Emily J. Silver 2012 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge many sources of inspiration, guidance, and clarity. First, I dedicate this manuscript to my co-advisors Dr. Anthony W. D’Amato and Dr. Shawn Fraver. I thank Tony for supporting my New England nostalgia, for endless patient explanations of statistical analyses, for sending me all over the state and country for enrichment opportunities, and advising me on the next steps of my career. To Shawn, my favorite deadwood-dependent organism, for countless hours in the field, persistent attention to timelines, grammar, details, and deadlines, and for career advice. I would like to thank Dr. Robert Blanchette, the most excited and knowledgeable third committee member I could have found. His enthusiasm and knowledge about mortality agents and fungi of the Great Lakes region helped me complete a very rewarding aspect of this research. Second, to the colleagues and professionals who provided ideas, snacks, drinks, and field work assistance: Miranda and Jordan Curzon, Paul Bolstad, Salli and Ben Dymond, Paul Klockow, Julie Hendrickson, Sascha Lodge, Justin Pszwaro, Eli Sagor, Mike Reinekeinen, Mike Carson, John Segari, Alaina Berger, Jane Foster, and Laura Reuling. Third to Dr. Tuomas Aakala (whose English is better than my own) for good humor, expertise, and patience coding in R and conceptualizing the spatial statistics (initially) beyond my comprehension. -

Pinus Sylvestris Breeding for Resistance Against Natural Infection of the Fungus Heterobasidion Annosum

Article Pinus sylvestris Breeding for Resistance against Natural Infection of the Fungus Heterobasidion annosum 1 1, 2 1 Raitis Rieksts-Riekstin, š , Pauls Zeltin, š * , Virgilijus Baliuckas , Lauma Bruna¯ , 1 1 Astra Zal, uma and Rolands Kapostin¯ , š 1 Latvian State Forest Research Institute Silava, 111 Rigas street, LV-2169 Salaspils, Latvia; [email protected] (R.R.-R.); [email protected] (L.B.); [email protected] (A.Z.); [email protected] (R.K.) 2 Forest Institute, Lithuanian Centre for Agriculture and Forestry, Department of Forest Tree Genetics and Breeding, Liepu St. 1, Girionys, LT-53101 Kaunas distr., Lithuania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 November 2019; Accepted: 19 December 2019; Published: 22 December 2019 Abstract: Increasing resistance against biotic and abiotic factors is an important goal of forest tree breeding. The aim of the present study was to develop a root rot resistance index for Scots pine breeding and evaluate its effectiveness. The productivity, branch diameter, branchiness, stem straightness, spike knots, and damage from natural infection of root rot in 154 Scots pine open-pollinated families from Latvia were evaluated through a progeny field trial at the age of 38 years. Trees with decline symptoms were sampled for fungal isolations. Based on this information and kriging estimates of root rot, 35 affected areas (average size: 108 m2; total 28% from the 1.5 ha trial) were delineated. Resistance index of a single tree was formed based on family adjusted proportion of live to infected trees and distance to the center of affected area. -

Verbenone Protects Chinese White Pine (Pinus Armandii)

Zhao et al.: Verbenone protects Chinese white pine (Pinus armandii) (Pinales: Pinaceae: Pinoideae) against Chinese white pine beetle (Dendroctonus armandii) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) attacks - 379 - VERBENONE PROTECTS CHINESE WHITE PINE (PINUS ARMANDII) (PINALES: PINACEAE: PINOIDEAE) AGAINST CHINESE WHITE PINE BEETLE (DENDROCTONUS ARMANDII) (COLEOPTERA: CURCULIONIDAE: SCOLYTINAE) ATTACKS ZHAO, M.1 – LIU, B.2 – ZHENG, J.2 – KANG, X.2 – CHEN, H.1* 1State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-Bioresources (South China Agricultural University), Guangdong Key Laboratory for Innovative Development and Utilization of Forest Plant Germplasm, College of Forestry and Landscape Architecture, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China 2College of Forestry, Northwest A & F University, Yangling, Shaanxi 712100, China *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]; phone/fax: +86-020-8528-0256 (Received 29th Aug 2020; accepted 19th Nov 2020) Abstract. Bark beetle anti-aggregation is important for tree protection due to its high efficiency and fewer potential negative environmental impacts. Densitometric variables of Pinus armandii were investigated in the case of healthy and attacked trees. The range of the ecological niche and attack density of Dendroctonus armandii in infested P. armandii trunk section were surveyed to provide a reference for positioning the anti-aggregation pheromone verbenone on healthy P. armandii trees. 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks after the application of verbenone, the mean attack density was significantly lower in the treatment group than in the control group (P < 0.01). At twelve months after anti-aggregation pheromone application, the mortality rate was evaluated. There was a significant difference between the control and treatment groups (chi-square test, P < 0.05). -

Preservative Treatment of Scots Pine and Norway Spruce

Preservative treatment of Scots pine and Norway spruce Ron Rhatigan Camille Freitag Silham El-Kasmi Jeffrey J. Morrell✳ Abstract The ability to treat Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and Norway spruce (Picea abies) with oilborne copper-8-quinolinolate or with waterborne chromated copper arsenate, ammoniacal copper zinc arsenate, or ammoniacal copper quaternary was assessed using commercial treatment facilities in the Pacific Northwest. In general, Scots pine was more easily treated than was Norway spruce, al- though neither species could be treated to the standards of the American Wood-Preservers’Association for dimension lumber without incising. Treatment was better with ammonia-based solutions, reflecting the ability of these systems to overcome the effects of pit as- piration and encrustation, and their ability to swell the wood to improve permeability. The results indicate that successful treatment of both species will require the use of incising. In addition, further research will be required to identify suitable schedules for success- fully treating Norway spruce with oilborne copper-8-quinolinolate. he past decade has witnessed dra- other applications where preservative data for inclusion in the appropriate matic changes in the patterns of world treatment will be essential for achieving American Wood-Preservers’ Associa- timber trade. Countries that formerly adequate performance, it is important to tion Standards (AWPA) (1). This report were net exporters of timber now find ensure that they meet treatability stan- describes an evaluation of commercial themselves importing an ever-increasing dards, in addition to the more obvious treatment of Scots pine and Norway variety of wood species to meet domestic code requirements for strength. -

IHCA Recommended Plant List

Residential Architectural Review Committee Recommended Plant List Plant Materials The following plant materials are intended to guide tree and shrub ADDITIONS to residential landscapes at Issaquah Highlands. Lot sizes, shade, wind and other factors place size and growth constraints on plants, especially trees, which are suitable for addition to existing landscapes. Other plant materials may be considered that have these characteristics and similar maintenance requirements. Additional species and varieties may be selected if authorized by the Issaquah Highlands Architectural Review Committee. This list is not exhaustive but does cover most of the “good doers” for Issaquah Highlands. Our microclimate is colder and harsher than those closer to Puget Sound. Plants not listed should be used with caution if their performance has not been observed at Issaquah Highlands. * Drought-tolerant plant ** Requires well-drained soil DECIDUOUS TREES: Small • Acer circinatum – Vine Maple • Acer griseum – Paperbark Maple • *Acer ginnala – Amur Maple • Oxydendrum arboreum – Sourwood • Acer palmation – Japanese Maple • *Prunus cerasifera var. – Purple Leaf Plum varieties • Amelanchier var. – Serviceberry varieties • Styrax japonicus – Japanese Snowbell • Cornus species, esp. kousa Medium • Acer rufinerve – Redvein Maple • Cornus florida (flowering dogwood) • *Acer pseudoplatanus – Sycamore Maple • Acer palmatum (Japanese maple, many) • • *Carpinus betulus – European Hornbeam Stewartia species (several) • *Parrotia persica – Persian Parrotia Columnar Narrow