Pinus Sylvestris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Forest Health & Biosecurity Working Papers OVERVIEW OF FOREST PESTS ROMANIA January 2007 Forest Resources Development Service Working Paper FBS/28E Forest Management Division FAO, Rome, Italy Forestry Department DISCLAIMER The aim of this document is to give an overview of the forest pest1 situation in Romania. It is not intended to be a comprehensive review. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. © FAO 2007 1 Pest: Any species, strain or biotype of plant, animal or pathogenic agent injurious to plants or plant products (FAO, 2004). Overview of forest pests - Romania TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..................................................................................................................... 1 Forest pests and diseases................................................................................................. 1 Naturally regenerating forests..................................................................................... 1 Insects ..................................................................................................................... 1 Diseases................................................................................................................ -

Estimating Numbers of Embryonic Lethals in Conifers

Heredity 69(1992)308—314 Received 26 November 1991 OThe Genetical Society of Great Britain Estimating numbers of embryonic lethals in conifers OUTI SAVOLAINEN, KATRI KARKKAINEN & HELMI KUITTINEN* Department of Genetics, University of Oulu, Oulu, Fin/and and *Department of Genetics, University of Helsinki, He/sink,, Fin/and Conifershave recessive lethal genes that eliminate most selfed embryos during seed development. It has been estimated that Scots pine has, on average, nine recessive lethals which act during seed development. Such high numbers are not consistent with the level of outcrossing, about 0.9—0.95, which has been observed in natural populations. Correcting for environmental mortality or using partial selfings provides significantly lower estimates of lethals. A similar discordance with numbers of lethals and observed outcrossing rates is true for other species. Keywords:embryoniclethals, inbreeding depression, outcrossing, Pinus sylvestris, Picea omorika. Introduction Reproduction system of conifers Conifershave no self-incompatibility mechanisms but Theproportion of self-pollination in conifers is early-acting inbreeding depression eliminates selfed variable. Sarvas (1962) suggested an average of 26 per embryos before seed maturation (Sarvas, 1962; cent for Pinus sylvestris, while Koski (1970) estimated Hagman & Mikkola, 1963). A genetic model for this values of self-fertilization around 10 per cent. The inbreeding depression has been developed by Koski genera Pinus and Picea have polyzygotic poly- (1971) and Bramlett & Popham (1971). Koski (1971, embryony, i.e. the ovules contain several archegonia. In 1973) has estimated that Pinus sylvestris and Picea Pinus sylvestris, the most common number of arche- abies have on average nine and 10 recessive lethals, gonia is two but it can range from one to five. -

SILVER BIRCH (BETULA PENDULA) at 200-230°C Raimo Alkn Risto Kotilainen

THERMAL BEHAVIOR OF SCOTS PINE (PINUS SYLVESTRIS) AND SILVER BIRCH (BETULA PENDULA) AT 200-230°C Postgraduate Student Raimo Alkn Professor and Risto Kotilainen Postgraduate Student Department of Chemistry, Laboratory of Applied Chemistry University of Jyvaskyla, PO. Box 35, FIN-40351 Jyvaskyla, Finland (Received April 1998) ABSTRACT Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and silver birch (Betuln pendula) were heated for 4-8 h in a steam atmosphere at low temperatures (200-230°C). The birch feedstock decomposed slightly more exten- sively (6.4-10.2 and 13515.2% of the initial DS at 200°C and 225"C, respectively) than the pine feedstock (5.7-7.0 and 11.1-15.2% at 205°C and 230°C. respectively). The results indicated that the differences in mass loss between these feedstocks were due to mainly the fact that carbohydrates (cellulose and hemicelluloses) were more amenable to various degradation reactions than lignin in intact wood. The degradation reactions were also monitored in both cases by determining changes in the elemental composition of the heat-treated products. Keywords: Heat treatment, carbohydrates, lignin, extractives, Pinus sylvestris, Betula pendula. INTRODUCTION content of hemicelluloses (25-30% of DS) In our previous experiments (AlCn et al. than hardwood (lignin and hemicelluloses are 2000), the thermal degradation of the structur- usually in the range 20-25 and 30-35% of al constituents (lignin and polysaccharides, DS, respectively). On the basis of these facts, i.e., cellulose and hemicelluloses) of Norway the thermal behavior of softwood and hard- spruce (Picea abies) was established under wood can be expected to be different, even at conditions (temperature range 180-225"C, low temperatures. -

California Juniper Picture Published with Permission of Bonsai Mirai

Junipers as bonsai V.3.2 April, 2017 Vianney Leduc 1- Introduction a. Esthetic quality The main beauty of junipers lies in the contrast between the living part and the deadwood California juniper Picture published with permission of Bonsai Mirai 2 Sierra juniper Picture published with permission of Bonsai Mirai 3 The influence of the contrast between living portion and deadwood comes from nature 4 We use this contrast seen in nature to style young junipers 5 b. Varieties of junipers Mature and compact foliage (e.g. Sargent juniper) Course foliage (e.g. Common juniper) Mature and juvenile foliage on same tree (e.g. San José juniper) 6 Examples of junipers with delicate and compact foliage o Sargent juniper (Juniperus chinesis sargentii) o Itoigawa juniper (Juniperus chinensis sargentii itoigawa) o Rocky Mountains Juniper (Juniperus scopulorum) o Blaauw juniper (Juniperus chinensis ‘blaauwii’) Examples of juniper with mature but longer foliage o San José juniper (Juniperus chinensis ‘san jose’) o California juniper (Juniperus californica) o Genévrier Sierra (Juniperus occidentalis australis) Examples of junipers with coarse foliage o Common juniper (Juniperus communis) o Needle juniper (Juniperus rigida) 7 c. Basic characteristics of junipers Relatively easy to cultivate Is ideal for most shape and styles of bonsai (except broom style) The wood is soft and easy to bend on younger trees Budding back ability varies greatly between sub-species o Some can bud back on the trunk o Others have a limited capacity Easy to find young specimen in nurseries We normally aim to create the look of an old tree with deadwood: branches should be pointing downward The strength of a juniper lies in its foliage Nice colour contrast between live veins and deadwood Deadwood will decay slowly Can develop a decent bonsai in relatively short time (4 to 5 years) Is an excellent species for all level of enthusiasts 8 2- Basic horticultural requirements a. -

Regeneration Methods to Reduce Pine Weevil Damage to Conifer Seedlings

Regeneration Methods to Reduce Pine Weevil Damage to Conifer Seedlings Magnus Petersson Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre Alnarp Doctoral thesis Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Alnarp 2004 Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae Silvestria 330 ISSN: 1401-6230 ISBN: 91 576 6714 4 © 2004 Magnus Petersson, Alnarp Tryck: SLU Service/Repro, Alnarp 2004 Abstract Petersson, M. 2004. Regeneration methods to reduce pine weevil damage to conifer seedlings. ISSN: 1401-6230, ISBN: 91 576 6714 4 Damage caused by the adult pine weevil Hylobius abietis (L.) (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) can be a major problem when regenerating with conifer seedlings in large parts of Europe. Weevils feeding on the stem bark of newly planted seedlings often cause high mortality in the first three to five years after planting following clear-cutting. The aims of the work underlying this thesis were to obtain more knowledge about the effects of selected regeneration methods (scarification, shelterwoods, and feeding barriers) that can reduce pine weevil damage to enable more effective counter-measures to be designed. Field experiments were performed in south central Sweden to study pine weevil damage amongst planted Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) H. Karst.) seedlings. The reduction of pine weevil damage by scarification, shelterwood and feeding barriers can be combined to obtain an additive effect. When all three methods were used simultaneously, mortality due to pine weevil damage was reduced to less than 10%. Two main types of feeding barriers were studied: coatings applied directly to the bark of the seedlings, and shields preventing the pine weevil from reaching the seedlings. It was concluded that the most efficient type of feeding barrier, reduced mortality caused by pine weevil about equally well as insecticide treatment, whereas other types were less effective. -

Pinus Nigra V

Technical guidelines for genetic conservation and use European black pine Pinus nigra V. Isajev1, B. Fady2, H. Semerci3 and V. Andonovski4 1 Forestry Faculty of Belgrade University, Belgrade, Serbia and Montenegro EUFORGEN 2 INRA, Mediterranean Forest Research Unit, Avignon, France 3 Forest Tree Seeds&Tree Breeding Research Directorate, Ankara,Turkey 4 Faculty of Forestry, Skopje, Macedonia FYR These Technical Guidelines are intended to assist those who cherish the valuable European black pine genepool and its inheritance, through conserving valuable seed sources or use in practical forestry. The focus is on conserving the genetic diversity of the species at the European scale. The recommendations provided in this module should be regarded as a commonly agreed basis to be complemented and further developed in local, national or regional conditions. The Guidelines are based on the available knowledge of the species and on widely accepted methods for the conservation of forest genetic resources. Biology and ecology although seed yield is abundant only every 2–4 years. Trees reach sexual maturity at 15–20 years in The European black pine (Pinus their natural habitat. Flowers nigra Arnold) grows up to 30 appear in May. Female inflores- (rarely 40–50) m tall, with a trunk cences are reddish, and male that is usually straight. The bark catkins are yellow. Fecundation is light grey to dark grey-brown, occurs 13 months after pollina- deeply furrowed longitudinally on tion. Cones are sessile and hori- older trees. The crown is broadly zontally spreading, 4–8 cm long, conical on young trees, umbrel- 2–4 cm wide, yellow-brown or la-shaped on older trees, light yellow and glossy. -

Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts Plant List

Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts Plant List This PDF document provides additional information to supplement the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management (CZM) Coastal Landscaping website. The plants listed below are good choices for the rugged coastal conditions of Massachusetts. The Coastal Beach Plant List, Coastal Dune Plant List, and Coastal Bank Plant List give recommended species for each specified location (some species overlap because they thrive in various conditions). Photos and descriptions of selected species can be found on the following pages: • Grasses and Perennials • Shrubs and Groundcovers • Trees CZM recommends using native plants wherever possible. The vast majority of the plants listed below are native (which, for purposes of this fact sheet, means they occur naturally in eastern Massachusetts). Certain non-native species with specific coastal landscaping advantages that are not known to be invasive have also been listed. These plants are labeled “not native,” and their state or country of origin is provided. (See definitions for native plant species and non-native plant species at the end of this fact sheet.) Coastal Beach Plant List Plant List for Sheltered Intertidal Areas Sheltered intertidal areas (between the low-tide and high-tide line) of beach, marsh, and even rocky environments are home to particular plant species that can tolerate extreme fluctuations in water, salinity, and temperature. The following plants are appropriate for these conditions along the Massachusetts coast. Black Grass (Juncus gerardii) native Marsh Elder (Iva frutescens) native Saltmarsh Cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) native Saltmeadow Cordgrass (Spartina patens) native Sea Lavender (Limonium carolinianum or nashii) native Spike Grass (Distichlis spicata) native Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) native Plant List for a Dry Beach Dry beach areas are home to plants that can tolerate wind, wind-blown sand, salt spray, and regular interaction with waves and flood waters. -

EVERGREEN TREES for NEBRASKA Justin Evertson & Bob Henrickson

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS EVERGREEN TREES FOR NEBRASKA Justin Evertson & Bob Henrickson. For more plant information, visit plantnebraska.org or retreenbraska.unl.edu Throughout much of the Great Plains, just a handful of species make up the majority of evergreens being planted. This makes them extremely vulnerable to challenges brought on by insects, extremes of weather, and diseases. Utilizing a variety of evergreen species results in a more diverse and resilient landscape that is more likely to survive whatever challenges come along. Geographic Adaptability: An E indicates plants suitable primarily to the Eastern half of the state while a W indicates plants that prefer the more arid environment of western Nebraska. All others are considered to be adaptable to most of Nebraska. Size Range: Expected average mature height x spread for Nebraska. Common & Proven Evergreen Trees 1. Arborvitae, Eastern ‐ Thuja occidentalis (E; narrow habit; vertically layered foliage; can be prone to ice storm damage; 20‐25’x 5‐15’; cultivars include ‘Techny’ and ‘Hetz Wintergreen’) 2. Arborvitae, Western ‐ Thuja plicata (E; similar to eastern Arborvitae but not as hardy; 25‐40’x 10‐20; ‘Green Giant’ is a common, fast growing hybrid growing to 60’ tall) 3. Douglasfir (Rocky Mountain) ‐ Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca (soft blue‐green needles; cones have distinctive turkey‐foot bract; graceful habit; avoid open sites; 50’x 30’) 4. Fir, Balsam ‐ Abies balsamea (E; narrow habit; balsam fragrance; avoid open, windswept sites; 45’x 20’) 5. Fir, Canaan ‐ Abies balsamea var. phanerolepis (E; similar to balsam fir; common Christmas tree; becoming popular as a landscape tree; very graceful; 45’x 20’) 6. -

Examensarbete I Ämnet Biologi

Examensarbete 2012:10 i ämnet biologi Comparison of bird communities in stands of introduced lodgepole pine and native Scots pine in Sweden Arvid Alm Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Fakulteten för skogsvetenskap Institutionen för vilt, fisk och miljö Examensarbete i biologi, 15 hp, G2E Umeå 2012 Examensarbete 2012:10 i ämnet biologi Comparison of bird communities in stands of introduced lodgepole pine and native Scots pine in Sweden Jämförelse mellan fågelsamhällen i bestånd av introducerad contortatall och inhemsk tall i Sverige Arvid Alm Keywords: Boreal forest, Pinus contorta, Pinus sylvestris, bird assemblage, Muscicapa striata Handledare: Jean-Michel Roberge & Adriaan de Jong 15 hp, G2E Examinator: Lars Edenius Kurskod EX0571 SLU, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Fakulteten för skogsvetenskap Faculty of Forestry Institutionen för vilt, fisk och miljö Dept. of Wildlife, Fish, and Environmental Studies Umeå 2012 Abstract The introduced lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) occupies more than 650 000 hectares in Sweden. There are some differences between lodgepole pine and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) forests which could affect bird assemblages, for example differences in canopy density and ground vegetation. Birds were surveyed in 14 localities in northern Sweden, each characterized by one middle-aged stand of lodgepole pine next to a stand of Scots pine. The two paired stands in each locality were planted by the forestry company SCA at the same time and in similar environment to evaluate the potential of lodgepole pine in Sweden. In those 14 localities, one to three point count stations were established in both the lodgepole pine and the Scots pine stand, depending on the size of the area. -

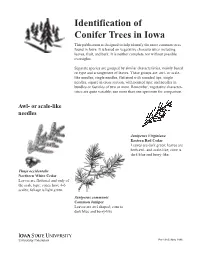

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

And Its Glucoside in Pinus Sylvestris Needles Consumed by Diprion Pini Larvae

Original article Quantitative variations of taxifolin and its glucoside in Pinus sylvestris needles consumed by Diprion pini larvae MA Auger C Jay-Allemand C Bastien C Geri 1 INRA, Station de Zoologie Forestière; 2 INRA, Station d’Amélioration des Arbres Forestiers, F-45160 Ardon, France (Received 22 March 1993; accepted 2 November 1993) Summary — The relationships between quantitative variations of 2 flavanonols in Scots pine needles and Diprion pini larvae mortality were studied. Those 2 compounds were characterized as taxifolin (T) and its glucoside (TG) after hydrolysis and analysis by TLC, HPLC and spectrophotometry. Quantitative differences between 30 clones were more important for TG than for T, nevertheless clones which presented a content of taxifolin higher than 1.5 mg g-1 DW showed a T/TG ratio equal to or greater than 0.5 (fig 2). Quantitative changes were also observed throughout the year. The amount of taxifolin peaked in autumn as those of its glucoside decreased (fig 3). Darkness also induced a gradual increase of T but no significant effect on TG (fig 4). Storage of twigs during feeding tests and insect defoliation both induced a strong glucosilation of taxifolin in needles (table I). High rates of mortality of Diprion pini larvae were associated with the presence of T and TG both in needles and faeces (table II). Preliminary experiments of feeding bioassay with needles supplemented by taxifolin showed a significant reduction of larval development but no direct effect on larval mortality (table III). Regulation processes between taxifolin and its glucoside, which could involve glucosidases and/or transferases, are discussed for the genetic and environmental factors studied. -

A Phytopharmacological Review on a Medicinal Plant: Juniperus Communis

Hindawi Publishing Corporation International Scholarly Research Notices Volume 2014, Article ID 634723, 6 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/634723 Review Article A Phytopharmacological Review on a Medicinal Plant: Juniperus communis Souravh Bais,1 Naresh Singh Gill,2 Nitan Rana,2 and Shandeep Shandil2 1 Department of Pharmacology, Rayat Institute of Pharmacy, Vpo Railmajra, Nawanshahr District, Punjab 144533, India 2 Rayat Institute of Pharmacy, Vpo Railmajra, Nawanshahr District, Punjab 144533, India Correspondence should be addressed to Souravh Bais; [email protected] Received 10 June 2014; Revised 28 September 2014; Accepted 15 October 2014; Published 11 November 2014 Academic Editor: Ronaldo F. do Nascimento Copyright © 2014 Souravh Bais et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are -pinene, -pinene, apigenin, sabinene, -sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others. This review includes