California Juniper Picture Published with Permission of Bonsai Mirai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts Plant List

Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts Plant List This PDF document provides additional information to supplement the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management (CZM) Coastal Landscaping website. The plants listed below are good choices for the rugged coastal conditions of Massachusetts. The Coastal Beach Plant List, Coastal Dune Plant List, and Coastal Bank Plant List give recommended species for each specified location (some species overlap because they thrive in various conditions). Photos and descriptions of selected species can be found on the following pages: • Grasses and Perennials • Shrubs and Groundcovers • Trees CZM recommends using native plants wherever possible. The vast majority of the plants listed below are native (which, for purposes of this fact sheet, means they occur naturally in eastern Massachusetts). Certain non-native species with specific coastal landscaping advantages that are not known to be invasive have also been listed. These plants are labeled “not native,” and their state or country of origin is provided. (See definitions for native plant species and non-native plant species at the end of this fact sheet.) Coastal Beach Plant List Plant List for Sheltered Intertidal Areas Sheltered intertidal areas (between the low-tide and high-tide line) of beach, marsh, and even rocky environments are home to particular plant species that can tolerate extreme fluctuations in water, salinity, and temperature. The following plants are appropriate for these conditions along the Massachusetts coast. Black Grass (Juncus gerardii) native Marsh Elder (Iva frutescens) native Saltmarsh Cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) native Saltmeadow Cordgrass (Spartina patens) native Sea Lavender (Limonium carolinianum or nashii) native Spike Grass (Distichlis spicata) native Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) native Plant List for a Dry Beach Dry beach areas are home to plants that can tolerate wind, wind-blown sand, salt spray, and regular interaction with waves and flood waters. -

A Phytopharmacological Review on a Medicinal Plant: Juniperus Communis

Hindawi Publishing Corporation International Scholarly Research Notices Volume 2014, Article ID 634723, 6 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/634723 Review Article A Phytopharmacological Review on a Medicinal Plant: Juniperus communis Souravh Bais,1 Naresh Singh Gill,2 Nitan Rana,2 and Shandeep Shandil2 1 Department of Pharmacology, Rayat Institute of Pharmacy, Vpo Railmajra, Nawanshahr District, Punjab 144533, India 2 Rayat Institute of Pharmacy, Vpo Railmajra, Nawanshahr District, Punjab 144533, India Correspondence should be addressed to Souravh Bais; [email protected] Received 10 June 2014; Revised 28 September 2014; Accepted 15 October 2014; Published 11 November 2014 Academic Editor: Ronaldo F. do Nascimento Copyright © 2014 Souravh Bais et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are -pinene, -pinene, apigenin, sabinene, -sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others. This review includes -

Phylogenetic Analyses of Juniperus Species in Turkey and Their Relations with Other Juniperus Based on Cpdna Supervisor: Prof

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY AYSUN DEMET GÜVENDİREN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BIOLOGY APRIL 2015 Approval of the thesis MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA submitted by AYSUN DEMET GÜVENDİREN in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Department of Biological Sciences, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Gülbin Dural Ünver Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Orhan Adalı Head of the Department, Biological Sciences Prof. Dr. Zeki Kaya Supervisor, Dept. of Biological Sciences METU Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Musa Doğan Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Prof. Dr. Zeki Kaya Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Prof.Dr. Hayri Duman Biology Dept., Gazi University Prof. Dr. İrfan Kandemir Biology Dept., Ankara University Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sertaç Önde Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Date: iii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Aysun Demet GÜVENDİREN Signature : iv ABSTRACT MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA Güvendiren, Aysun Demet Ph.D., Department of Biological Sciences Supervisor: Prof. -

The Ecological Status of Juniperus Foetidissima Forest Stands in the Mt

sustainability Article The Ecological Status of Juniperus foetidissima Forest Stands in the Mt. Oiti-Natura 2000 Site in Greece Nikolaos Proutsos * , Alexandra Solomou, George Karetsos, Konstantinia Tsagari, George Mantakas, Konstantinos Kaoukis, Athanassios Bourletsikas and George Lyrintzis Hellenic Agricultural Organization “Demeter”, Institute of Mediterranean Forest Ecosystems, Terma Alkmanos, 11528 Athens, Greece; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (G.K.); [email protected] (K.T.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (K.K.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (G.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-2107-787535 Abstract: Junipers face multiple threats induced both by climate and land use changes, impacting their expansion and reproductive dynamics. The aim of this work is to evaluate the ecological status of Juniperus foetidissima Willd. forest stands in the protected Natura 2000 site of Mt. Oiti in Greece. The study of the ecological status is important for designing and implementing active management and conservation actions for the species’ protection. Tree size characteristics (height, breast height diameter), age, reproductive dynamics, seed production and viability, tree density, sex, and habitat expansion were examined. The data analysis revealed a generally good ecological status of the habitat with high plant diversity. However, at the different juniper stands, subpopulations present high variability and face different problems, such as poor tree density, reduced numbers of juvenile trees or poor seed production, inadequate male:female ratios, a small number of female trees, reduced numbers of seeds with viable embryos, competition with other woody species, grazing, and Citation: Proutsos, N.; Solomou, A.; illegal logging. From the results, the need for site-specific active management and interventions is Karetsos, G.; Tsagari, K.; Mantakas, demonstrated in order to preserve or achieve the good status of the habitat at all stands in the region. -

![Downloaded from the BSBI Distribution Database That Spanned from “Before 1738” to January 2020 [37]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9586/downloaded-from-the-bsbi-distribution-database-that-spanned-from-before-1738-to-january-2020-37-1349586.webp)

Downloaded from the BSBI Distribution Database That Spanned from “Before 1738” to January 2020 [37]

Article Investigating the Role of Restoration Plantings in Introducing Disease—A Case Study Using Phytophthora Flora Donald 1,2,3,* , Bethan V. Purse 1 and Sarah Green 3,* 1 UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Maclean Building, Benson Lane, Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX10 8BB, UK; [email protected] 2 Department of Plant Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EA, UK 3 Forest Research, Northern Research Station, Roslin, Midlothian EH25 9SY, UK * Correspondence: fl[email protected] (F.D.); [email protected] (S.G.) Abstract: Translocating plants to natural habitats is a long-standing conservation practice but is growing in magnitude to deliver international targets to mitigate climate change and reverse bio- diversity loss. Concurrently, outbreaks of novel plant pests and pathogens are multiplying with increased global trade network connectivity and larger volumes of imported plants, raising concerns that restoration plantings may act as introductory disease pathways. We used UK common juniper, subject since ~1995 to conservation plantings and now experiencing significant mortality from the non-native pathogen Phytophthora austrocedri Gresl. & E. M. Hansen, as an example species to explore the availability of monitoring data that could be used to assess disease risks posed by planting. We compiled spatial records of juniper planting including qualitative data on sources of planting material, propagation settings and organization types that managed planting projects. We found that juniper planting activity expanded every decade since 1990 across the UK and while not all planting resulted in outbreaks, 19% of P. austrocedri detections were found within 2 km of a known planting. -

Cupressaceae – Cypress Family

CUPRESSACEAE – CYPRESS FAMILY Plant: shrubs and small to large trees, with resin Stem: woody Root: Leaves: evergreen (some deciduous); opposite or whorled, small, crowded and often overlapping and scale-like or sometimes awl- or needle-like Flowers: imperfect (monoecious or dioecious); no true flowers; male cones small and herbaceous, spore-forming; female cones woody (berry-like in junipers), scales opposite or in 3’s, without bracts Fruit: no true fruits; berry-like or drupe-like; 1-2 seeds at cone-scale, often with 2 wings Other: sometimes included with Pinaceae; locally mostly ‘cedars’; Division Coniferophyta (Conifers), Gymnosperm Group Genera: 30+ genera; locally Chamaecyparis, Juniperus (juniper), Thuja (arbor vitae), Taxodium (cypress) WARNING – family descriptions are only a layman’s guide and should not be used as definitive Flower Morphology in the Cupressaceae (Cypress Family) Examples of some common genera Common Juniper Juniperus communis L. var. depressa Pursh Bald Cypress Taxodium distichum (L.) L.C. Rich. Arbor Vitae [Northern White Cedar] Eastern Red Cedar [Juniper] Thuja occidentalis L. Juniperus virginiana L. var. virginiana CUPRESSACEAE – CYPRESS FAMILY Ashe's Juniper; Juniperus ashei J. Buchholz Common Juniper; Juniperus communis L. var. depressa Pursh Utah Juniper; Juniperus osteosperma (Torr.) Little Eastern Red Cedar [Juniper]; Juniperus virginiana L. var. virginiana Bald Cypress; Taxodium distichum (L.) L.C. Rich. Arbor Vitae [Northern White Cedar]; Thuja occidentalis L. Ashe's Juniper USDA Juniperus ashei J. Buchholz Cupressaceae (Cypress Family) Ashe Juniper Natural Area, Stone County, Missouri Notes: shrub to small tree; leaves evergreen, scale- like in 2-4 ranks, somewhat ovate with acute tip, no glands but resinous, margin with minute teeth; bark gray-brown-reddish, shreds easily, white blotches ring trunk and branches; fruit globular, fleshy and hard, blue, glaucous; dolostone bluffs and glades [V Max Brown, 2010] Common Juniper USDA Juniperus communis L. -

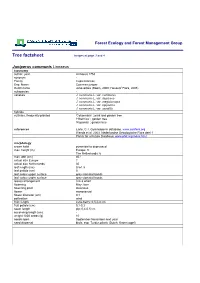

Tree Factsheet Images at Page 3 and 4

Forest Ecology and Forest Management Group Tree factsheet images at page 3 and 4 Juniperus communi s Linnaeus taxonomy author, year Linnaeus 1753 synonym - Family Cupressaceae Eng. Name Common juniper Dutch name Jeneverbes (Boom, 2000; Heukels’ Flora, 2005) subspecies - varieties J. communis L. var. communis J. communis L. var. depressa J. communis L. var. megistocarpa J. communis L. var. nipponica J. communis L. var. saxatilis hybrids - cultivars, frequently planted ‘Columnaris’ ; park and garden tree ‘Hibernica’ ; garden tree ‘Repanda’ ; garden tree references Earle, C.J. Gymnosperm database. www.conifers.org Weeda et al. 2003. Nederlandse Oecologische Flora deel 1 Plants for a Future Database; www.pfaf.org/index.html morphology crown habit pyramidal to depressed max. height (m) Europe: 9 The Netherlands: 6 max. dbh (cm) 40? actual size Europe ? actual size Netherlands 30 leaf length (cm) 0,5-1,5 leaf petiole (cm) 0 leaf colour upper surface grey stomatal bands leaf colour under surface grey stomatal bands leaves arrangement 3 in a whorl flowering May-June flowering plant dioecious flower monosexual flower diameter (cm) 0,1 pollination wind fruit; length cone-berry; 0,5-0,8 cm fruit petiole (cm) 0,1-0,2 seed; length pip; 0,4-0,5 cm seed-wing length (cm) - weight 1000 seeds (g) 10 seeds ripen September-November next year seed dispersal birds, esp. Turdus pilaris (Dutch: Kramsvogel) habitat natural distribution Northern Hemisphere in N.W. Europe since 11.000 BC natural areas The Netherlands indigenous geological landscape types The Netherlands drift sand area, coversand area, ice-pushed ridges (Hoek 1997) forested areas The Netherlands sandy soils; former heath fields area Netherlands 1600 ha (inventory Goudzwaard) % of forest trees in the Netherlands <1% soil type indifferent pH-KCl 4-7 soil fertility poor to medium rich light light demanding shade tolerance 1.7 (0=no tolerance to 5=max. -

Black Crowberry (Empetrum Nigrum) L

Conservation Assessment for Black crowberry (Empetrum nigrum) L. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region March 2002 Hiawatha National Forest This document is undergoing peer review, comments welcome CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT FOR BLACK CROWBERRY (EMPETRUM NIGRUM) L. 1 This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on the subject taxon or community; or this document was prepared by another organization and provides information to serve as a Conservation Assessment for the Eastern Region of the Forest Service. It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service - Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 580 Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT FOR BLACK CROWBERRY (EMPETRUM NIGRUM) L. 1 Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................... 4 NOMENCLATURE AND TAXONOMY .................................................. 4 DESCRIPTION OF SPECIES .................................................................... 5 HABITAT TYPES -

The Tudor Richards Natural History and Forestry Trail

THE TUDOR RICHARDS NATURAL HISTORY AND FORESTRY TRAIL A Self-Guiding Educational Tour THE TUDOR RICHARDS NATURAL HISTORY AND FORESTRY TRAIL A Self-Guiding Educational Tour he countryside becomes more meaningful and interesting as we learn more about its history and T ecology, that branch of biology that studies interactions among all living things and their environment. Humans have always depended on the land and always will. It provides not only water, food, fiber and minerals but also scenery, fresh air and space. Now, with populations exploding and cities expanding relentlessly, we must make wiser use of our natural resources. We must also set aside some areas for the study of Nature's ways so that we can understand them better and work with rather than against them. This is what conservation is about. Beaver Brook Association invites you to follow this Natural History and Forestry Trail slowly and thoughtfully. We suggest you not try to see everything on the first time but plan future visits to this and our other trails, and at different seasons. This guide is your "instructor" on the self-guiding walk. Trail Explanation This trail is about one mile long and can be walked in about 40 minutes, but to truly appreciate the many natural features, you should plan on spending at least twice that much time. The trail is marked by white arrows to avoid confusion with other trails, and all features have numbered markers to correspond with this guide. Most of the items marked by signs can be seen at any time of year unless dormant or hidden by snow. -

Deer & Rabbit Resistant Trees & Shrubs

Deer & Rabbit Resistant Trees & Shrubs A list of trees and shrubs that are less likely to be browsed by deer and rabbits * = xeric plants Deciduous Shrubs Alleghany Viburnum (Viburnum x rhytidophylloides) Korean Dwarf Lilac (Syringa meyeri) Alpine Current (Ribes alpinum) Korean Spice Viburnum (Viburnum carlesii) Anthony Waterer Spirea (Spirea japonica) Mentor Barberry (Berberis x mentorensis) Apache Plume (Fallugia paradoxa)* Miss Kim Lilac (Syringa patula) Arnold Red Honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica)* Mohican Viburnum (Viburnum lantana)* Blue Mist Spirea (Caryopteris x clandonensis)* Nanking Cherry (Prunus tomentosa) Boulder Raspberry (Rubus delicious)* Persian Lilac (Syringa x persica) Burning Bush (Euonymus alatus) Pixwell Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum pixwell) Butterfly Bush (Buddleia davidii) Potentilla (Potentilla spp.) Cardinal Dogwood (Cornus sericea ‘Cardinal’) Purple Smoke Tree (Cotinus coggygria) Cheyenne Privet (Ligustrum vulgare ‘Cheyenne’)* Rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus nauseosus)* Chinese Lilac (Syringa x chinensis) Red Barberry (Berberis thunbergii ‘Atropurpurea’) Common Purple Lilac (Syringa vulgaris)* Red Flowering Quince (Chaenomeles japonica) Common White Lilac (Syringa vulgaris alba)* Red Twig Dogwood (Cornus sericea ‘Baileyi’) Crimson Pygmy Barberry (Berberis thunbergii)* Rose-of-Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus) Curl Leaf Mountain Mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius)* Rosy Glow Barberry (Berberis thunbergii) Cutleaf Sumac (Rhus glabra ‘Laciniata’)* Russian Sage (Perovskia artiplicifolia)* Dwarf Burning Bush (Euonymus alatus ‘Compacta’) -

Vascular Plant Species Checklist and Rare Plants of Fossil Butte National

Vascular Plant Species Checklist And Rare Plants of Fossil Butte National Monument Physaria condensata by Jane Dorn from Dorn & Dorn (1980) Prepared for the National Park Service Northern Colorado Plateau Network By Walter Fertig Wyoming Natural Diversity Database University of Wyoming PO Box 3381, Laramie, WY 82071 9 October 2000 Table of Contents Page # Introduction . 3 Study Area . 3 Methods . 5 Results . 5 Summary of Plant Inventory Work at Fossil Butte National Monument . 5 Flora of Fossil Butte National Monument . 7 Rare Plants of Fossil Butte National Monument . 7 Other Noteworthy Plant Species from Fossil Butte National Monument . 8 Discussion and Recommendations . 8 Acknowledgments . 10 Literature Cited . 11 Figures, Tables, and Appendices Figure 1. Fossil Butte National Monument . 4 Figure 2. Increase in Number of Plant Species Recorded at Fossil Butte National Monument, 1973-2000 . 9 Table 1. Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Fossil Butte National Monument . 13 Table 2. Rejected Plant Taxa . 32 Table 3. Potential Vascular Plants of Fossil Butte National Monument . 35 Appendix A. Rare Plants of Fossil Butte National Monument . 41 2 INTRODUCTION The National Park Service established Fossil Butte National Monument in October 1972 to preserve significant deposits of fossilized freshwater fish, aquatic organisms, and plants from the Eocene-age Green River Formation. In addition to fossils, the Monument also preserves a mosaic of 12 high desert and montane foothills vegetation types (Dorn et al. 1984; Jones 1993) and over 600 species of vertebrates and vascular plants (Beetle and Marlow 1974; Rado 1976, Clark 1977, Dorn et al. 1984; Kyte 2000). From a conservation perspective, Fossil Butte National Monument is especially significant because it is one of only two managed areas in the basins of southwestern Wyoming to be permanently protected and managed with an emphasis on maintaining biological processes (Merrill et al. -

Appendix a Plant List Appendix A: Plant List Black Spruce (Picea Mariana) White Pine (Pinus Strobus) Black Cherry (Prunus Serotina) Choke Cherry (Prunus Virginiana) 1

Appendix A Plant List Appendix A: Plant List Black Spruce (Picea mariana) White Pine (Pinus strobus) Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) Choke Cherry (Prunus virginiana) 1. Salt-Tolerant Plants These plant species are suitable for planting within Shrubs 80 feet of a roadside that is subject to de-icing and For Dry, Sunny Areas anti-icing application of salts. Bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica) Lowbush Blueberry (Vaccinium augustifolium) Ground Juniper (Juniperus communis) Trees New Jersey Tea (Ceanothus americanus) White Oak (Quercus alba) Sweet Fern (Comptonia peregrina) Red Oak (Quercus rubra) White Poplar (Populus alba) For Shaded Areas Blue Spruce (Picea pungens) Hazelnut (Corylus americana, C. cornuta) Green Ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia) Eastern Cottonwood (Populus deltoides) Swamp Azalea (Rhododendron viscosum) Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus) Viburnums (V. acerfolium, V. cassinoides, V. Hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) alnifolium) Pitch Pine (Pinus rigida) Honeylocust (Gleditsia triacanthos) For Moist Sites Dogwoods (Cornus spp.) Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) Shrubs Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) Forsythia (Forsythia x intermedia) Pussy Willow (Salix discolor) Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis) Shadbush Serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis) Bayberry (Myrica pennsylvanica) Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) Black Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) Spirea (Spirea latifolia) Red Chokeberry (Aronia arbutifolia) Swamp azalea (Rhododendron viscosum) Marsh Elder or High Tide Bush (Iva frutescens) Sweet Pepperbush