Apparent Hybridisation of Firecrest and Goldcrest F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geographic and Individual Variation in Carotenoid Coloration in Golden-Crowned Kinglets (Regulus Satrapa)

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2009 Geographic and individual variation in carotenoid coloration in golden-crowned kinglets (Regulus satrapa) Celia Chui University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Chui, Celia, "Geographic and individual variation in carotenoid coloration in golden-crowned kinglets (Regulus satrapa)" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 280. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/280 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. GEOGRAPHIC AND INDIVIDUAL VARIATION IN CAROTENOID COLORATION IN GOLDEN-CROWNED KINGLETS ( REGULUS SATRAPA ) by Celia Kwok See Chui A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through Biological Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2009 © 2009 Celia Kwok See Chui Geographic and individual variation in carotenoid coloration in golden-crowned kinglets (Regulus satrapa ) by Celia Kwok See Chui APPROVED BY: ______________________________________________ Dr. -

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Red-Breasted Nuthatch and Golden-Crowned Kinglet

Red-breasted Nuthatch and Golden-crowned Kinglet: The First Nests for South Carolina and Other Chattooga Records Frank Renfrow 611 South O’Fallon Avenue, Bellevue, KY 41073 [email protected] Introduction The Chattooga Recreation Area (referred to as CRA for purposes of this article), located adjacent to the Walhalla National Fish Hatchery (780 m) within Sumter National Forest, Oconee Co., South Carolina, has long been noted as a unique natural area within the state. The picnic area in particular, situated along the East Fork of the Chattooga River, contains an old-growth stand of White Pine (Pinus strobus) and Canada Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) with state records for both species as well as an impressive understory of Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia) and Great Laurel (Rhododendron maximum) (Gaddy 2000). Nesting birds at CRA not found outside of the northwestern corner of the state include Black-throated Blue Warbler (Dendroica caerulescens) and Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis). Breeding evidence of two other species of northern affinities, Red-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta canadensis) and Golden-crowned Kinglet (Regulus satrapa) has previously been documented at this location (Post and Gauthreaux 1989, Oberle and Forsythe 1995). However, nest records of these two species have not been documented prior to this study. The summer occurrence of two other northern species on the South Carolina side of the Chattooga River, Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) and Winter Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) has not been previously recorded. Only a few summer records of the Blackburnian Warbler (Dendroica fusca) have been noted for the state. Extensive field observations were made by the author in the Chattooga River area of Georgia and South Carolina during the breeding seasons of 2000, 2002 and 2003 in order to verify breeding of bird species of northern affinities. -

Estimating Numbers of Embryonic Lethals in Conifers

Heredity 69(1992)308—314 Received 26 November 1991 OThe Genetical Society of Great Britain Estimating numbers of embryonic lethals in conifers OUTI SAVOLAINEN, KATRI KARKKAINEN & HELMI KUITTINEN* Department of Genetics, University of Oulu, Oulu, Fin/and and *Department of Genetics, University of Helsinki, He/sink,, Fin/and Conifershave recessive lethal genes that eliminate most selfed embryos during seed development. It has been estimated that Scots pine has, on average, nine recessive lethals which act during seed development. Such high numbers are not consistent with the level of outcrossing, about 0.9—0.95, which has been observed in natural populations. Correcting for environmental mortality or using partial selfings provides significantly lower estimates of lethals. A similar discordance with numbers of lethals and observed outcrossing rates is true for other species. Keywords:embryoniclethals, inbreeding depression, outcrossing, Pinus sylvestris, Picea omorika. Introduction Reproduction system of conifers Conifershave no self-incompatibility mechanisms but Theproportion of self-pollination in conifers is early-acting inbreeding depression eliminates selfed variable. Sarvas (1962) suggested an average of 26 per embryos before seed maturation (Sarvas, 1962; cent for Pinus sylvestris, while Koski (1970) estimated Hagman & Mikkola, 1963). A genetic model for this values of self-fertilization around 10 per cent. The inbreeding depression has been developed by Koski genera Pinus and Picea have polyzygotic poly- (1971) and Bramlett & Popham (1971). Koski (1971, embryony, i.e. the ovules contain several archegonia. In 1973) has estimated that Pinus sylvestris and Picea Pinus sylvestris, the most common number of arche- abies have on average nine and 10 recessive lethals, gonia is two but it can range from one to five. -

SILVER BIRCH (BETULA PENDULA) at 200-230°C Raimo Alkn Risto Kotilainen

THERMAL BEHAVIOR OF SCOTS PINE (PINUS SYLVESTRIS) AND SILVER BIRCH (BETULA PENDULA) AT 200-230°C Postgraduate Student Raimo Alkn Professor and Risto Kotilainen Postgraduate Student Department of Chemistry, Laboratory of Applied Chemistry University of Jyvaskyla, PO. Box 35, FIN-40351 Jyvaskyla, Finland (Received April 1998) ABSTRACT Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and silver birch (Betuln pendula) were heated for 4-8 h in a steam atmosphere at low temperatures (200-230°C). The birch feedstock decomposed slightly more exten- sively (6.4-10.2 and 13515.2% of the initial DS at 200°C and 225"C, respectively) than the pine feedstock (5.7-7.0 and 11.1-15.2% at 205°C and 230°C. respectively). The results indicated that the differences in mass loss between these feedstocks were due to mainly the fact that carbohydrates (cellulose and hemicelluloses) were more amenable to various degradation reactions than lignin in intact wood. The degradation reactions were also monitored in both cases by determining changes in the elemental composition of the heat-treated products. Keywords: Heat treatment, carbohydrates, lignin, extractives, Pinus sylvestris, Betula pendula. INTRODUCTION content of hemicelluloses (25-30% of DS) In our previous experiments (AlCn et al. than hardwood (lignin and hemicelluloses are 2000), the thermal degradation of the structur- usually in the range 20-25 and 30-35% of al constituents (lignin and polysaccharides, DS, respectively). On the basis of these facts, i.e., cellulose and hemicelluloses) of Norway the thermal behavior of softwood and hard- spruce (Picea abies) was established under wood can be expected to be different, even at conditions (temperature range 180-225"C, low temperatures. -

Examensarbete I Ämnet Biologi

Examensarbete 2012:10 i ämnet biologi Comparison of bird communities in stands of introduced lodgepole pine and native Scots pine in Sweden Arvid Alm Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Fakulteten för skogsvetenskap Institutionen för vilt, fisk och miljö Examensarbete i biologi, 15 hp, G2E Umeå 2012 Examensarbete 2012:10 i ämnet biologi Comparison of bird communities in stands of introduced lodgepole pine and native Scots pine in Sweden Jämförelse mellan fågelsamhällen i bestånd av introducerad contortatall och inhemsk tall i Sverige Arvid Alm Keywords: Boreal forest, Pinus contorta, Pinus sylvestris, bird assemblage, Muscicapa striata Handledare: Jean-Michel Roberge & Adriaan de Jong 15 hp, G2E Examinator: Lars Edenius Kurskod EX0571 SLU, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Fakulteten för skogsvetenskap Faculty of Forestry Institutionen för vilt, fisk och miljö Dept. of Wildlife, Fish, and Environmental Studies Umeå 2012 Abstract The introduced lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) occupies more than 650 000 hectares in Sweden. There are some differences between lodgepole pine and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) forests which could affect bird assemblages, for example differences in canopy density and ground vegetation. Birds were surveyed in 14 localities in northern Sweden, each characterized by one middle-aged stand of lodgepole pine next to a stand of Scots pine. The two paired stands in each locality were planted by the forestry company SCA at the same time and in similar environment to evaluate the potential of lodgepole pine in Sweden. In those 14 localities, one to three point count stations were established in both the lodgepole pine and the Scots pine stand, depending on the size of the area. -

Ruby-Crowned Kinglet Regulus Calendula the Ruby-Crowned Kinglet Is a Winter Visitor, Com- Monest in Riparian and Oak Woodland

Kinglets — Family Regulidae 427 Ruby-crowned Kinglet Regulus calendula The Ruby-crowned Kinglet is a winter visitor, com- monest in riparian and oak woodland. It uses a wide variety of other habitats too, from urban eucalyptus trees to pines and firs in the mountains to desert oases. The Ruby-crowned Kinglet is San Diego County’s leading practitioner of hover-gleaning: hovering momentarily at a leaf to glean minute insects. A northward contraction of the species’ breeding range is not yet reflected in a decline in its winter numbers. Winter: The Ruby-crowned Kinglet is one of San Diego Photo by Anthony Mercieca County’s most widespread winter visitors, recorded in 96% of all atlas squares covered. Only in the bleakest feet the Ruby-crowned Kinglet is common in winter, with parts of the Anza–Borrego Desert, near the Imperial counts up to 25 on West Mesa, Cuyamaca Mountains County line, is it likely to be missed. It is most abun- (N20), 9 January and 6 February 1999 (B. Siegel) and dant in northwestern San Diego County, where riparian 23 near Filaree Flat, Laguna Mountains (N22) 9 January woodland is most extensive. During the atlas period the 1999 (G. L. Rogers). Around the summit of San Diego highest counts were around Lake Hodges (K10), of up to County’s highest peak, Hot Springs Mountain (E20), C. R. 137 on 22 December 2000 (R. L. Barber et al.). Farther Mahrdt and K. L. Weaver noted it repeatedly, with a max- inland numbers can be quite high as well, up to 40 around imum five on 9 December 2000. -

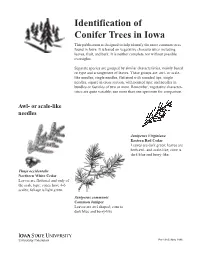

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

Ruby-Crowned Kinglet Regulus Calendula

Ruby-crowned Kinglet Regulus calendula Folk Name: Je-dit Status: Winter Resident Abundance: Fairly Common to Common Habitat: Coniferous forests or mixed hardwood forests The Ruby-crowned Kinglet averages half an inch larger than its golden-crowned cousin. It is olive green above and buffy below. It has no eye stripe, rather it has a white eye-ring. It has two white wing bars and one black. The female lacks a colorful crown, but the male has a bright ruby-red crown that is especially visible when the bird is agitated. When the male is calm, the red crown can be quite difficult to see. Rudy-crowned Kinglets are often heard before they are seen. Their call is a sharpje-dit, je-dit. In this region, Ruby-crowned Kinglets are a bit less common than Golden-crowned Kinglets during the winter. Both of our kinglets are regularly observed foraging song has been described as “remarkably sweet and along the end of tree branches and periodically flicking melodious and is rated by some as both louder and more their wings. They survive the winter by foraging in mixed- varied than that of the canary.” species flocks in search of spiders, insects, arthropod A member of the North Carolina Bird Club contributed eggs, and an occasional seed or berry. A few have been this experience for readers of the Statesville Record and observed feeding on the berries of winged sumac (Rhus Landmark on January 13, 1941: copallina) at prairie restoration sites in Mecklenburg County. Ruby-crowned Kinglets are occasionally seen One morning while I was frying bacon for the visiting backyard suet feeders in the winter. -

Genetic Differentiation Between North American Kinglets And

386 ShortCommunications [Auk,Vol. 105 GeneticDifferentiation BetweenNorth AmericanKinglets and Comparisons with Three Allied Passerines JAMESL. INGOLD,• LEE A. WEIGT, AND SHELDONI. GUTTMAN Departmentof Zoology,Miami University,Oxford, Ohio 45056 USA The genusRegulus is composedof five species,two Rogers'genetic distance (Wright 1978)values (Fig. 1). of which are native to the Western Hemisphere We alsoanalyzed the allozymesas charactersto avoid (Clements1978). Mayr and Short (1970) discussedthe the problems and lossof information associatedwith possible relationshipsbetween the Ruby-crowned reducingelectrophoretic data setsto distancecoeffi- Kinglet (R. calendula)and the Golden-crownedKing- cients(Farris 1981,Felsenstein 1984). Branch lengths let (R. satrapa).They suggestedthat the Golden- of cladogramsderived in this manner have biological crowned Kinglet is most closelyrelated to the Gold- meaning. There are several ways to code and order crest (R. regulus)of the Palearcticfaunal region and allozyme characterstates, however, and no general that the Ruby-crownedKinglet is not closelyrelated concensusexists on the most appropriate approach to any of the other speciesof kinglet, even though it (reviewed by Buth 1984).We usedthe alleles as char- has hybridized with the Golden-crownedKinglet acters with the character statesbeing "presence" or (Gray 1958).We presentgenetic evidence that the two "absence";character coding in this manner acknowl- North American kinglets are not closelyrelated. edgesthe presence(or absence)of alleles rather than The birds usedin this study were mist-nettednear particular suites of alleles. The character-statedata Oxford,Butler Co., Ohio, and were collectedfor part were analyzedwith the PhylogeneticAnalysis Using of a larger studyon the historyof the North American Parsimony (PAUP) provided by Swofford (1984). avifauna. Yellow-breasted Chats (Icteriavirens; n = 7) Character stateswere weighted such that each locus and Common Yellowthroats (Geothlypistrichas; n = provided equal information; the tree (Fig. -

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to Identify the Level of Threat to Plants

Ex-Situ Conservation at Scott Arboretum Public gardens and arboreta are more than just pretty places. They serve as an insurance policy for the future through their well managed ex situ collections. Ex situ conservation focuses on safeguarding species by keeping them in places such as seed banks or living collections. In situ means "on site", so in situ conservation is the conservation of species diversity within normal and natural habitats and ecosystems. The Scott Arboretum is a member of Botanical Gardens Conservation International (BGCI), which works with botanic gardens around the world and other conservation partners to secure plant diversity for the benefit of people and the planet. The aim of BGCI is to ensure that threatened species are secure in botanic garden collections as an insurance policy against loss in the wild. Their work encompasses supporting botanic garden development where this is needed and addressing capacity building needs. They support ex situ conservation for priority species, with a focus on linking ex situ conservation with species conservation in natural habitats and they work with botanic gardens on the development and implementation of habitat restoration and education projects. BGCI uses the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to identify the level of threat to plants. In-depth analyses of the data contained in the IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, Red List are published periodically (usually at least once every four years). The results from the analysis of the data contained in the 2008 update of the IUCN Red List are published in The 2008 Review of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; see www.iucn.org/redlist for further details. -

Lot # Item Description 1 12" Cased Ruby Flame Crest Bowl W/Double

Lot # Item description 1 12" Cased Ruby Flame Crest Bowl w/double crimp 2 8" Dave Fetty Hanging Hearts Hat 3 Blue Spiral Optic Water Set - pitcher & 5 tumblers have cobalt handles, 4 tumblers, 4 coasters, 9 stirrers 4 11" Mulberry Hand Vase 5 x2 4" Mini Vases - Beaded Melon Goldenrod & Mandarin Red Hobnail - x2 6 x2 Ebony Crest Fan Vase & Apple Blossom Crest Heart Dish - x2 7 x2 French Opal Basketweave Bowl & Crystal Cigarette Box/Silver Tray - x2 8 Cobalt Hanging Heart Egg 9 OOAK Aqua Crest Ewer w/Ruby Handle - whimsey 10 Tie Dye Happy Cat & Happy Kitty 11 Charleton Hat Vase w/enameled roses 12 2 Ruby Dolphin Candlesticks 13 Spring Pink Nymph w/frog & bowl 14 White Satin Working Elephant w/open trunk 15 Ruby Lincoln Inn Creamer & Sugar 16 Mongolian Green Lily of the Valley Bell 17 x2 Crystal Satin Verlys Lovebird Vase & Cobalt Console Bowl - x2 18 x2 Wild Rose Jacqueline Vase & Cranberry Opal Spiral Optic Vase - x2 19 Set of 4 Ruby Jay-Cee Etched Plates Circa 1930-1955 20 3 Piece Fairy Light - Ruby Stretch Sample w/Sunflowers hp by Frances Burton 21 9.5" Covered Footed Candy Dish #2/8 2016 Penguins by Frances Burton 22 15" Amphora w/brass stand #5/6 2016 Woodpecker by JK Spindler 23 9" Rosalene Basket Glass Legacy 95 Years by Pam Hayhurst 24 10" Nouveau Blue Satin Overlay Vase 8 Family Signatures by S Waters 25 9"Milk Ruby Overlay Satin Vase w/sunflower 9 Family Signature by CC Hardman 26 Opal Halloween Alley Cat #5/20 2016 by Kim Barley 27 Jadeite Alley Cat w/Bluebird Nest #1/7 2016 by M Kibbe 28 Ringneck Drake & Duck Mallard Set 2016