Regeneration Methods to Reduce Pine Weevil Damage to Conifer Seedlings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Forest Health & Biosecurity Working Papers OVERVIEW OF FOREST PESTS ROMANIA January 2007 Forest Resources Development Service Working Paper FBS/28E Forest Management Division FAO, Rome, Italy Forestry Department DISCLAIMER The aim of this document is to give an overview of the forest pest1 situation in Romania. It is not intended to be a comprehensive review. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. © FAO 2007 1 Pest: Any species, strain or biotype of plant, animal or pathogenic agent injurious to plants or plant products (FAO, 2004). Overview of forest pests - Romania TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..................................................................................................................... 1 Forest pests and diseases................................................................................................. 1 Naturally regenerating forests..................................................................................... 1 Insects ..................................................................................................................... 1 Diseases................................................................................................................ -

Ophiostomatoid Fungal Infection and Insect Diversity in a Mature Loblolly Pine Stand

Ophiostomatoid Fungal Infection and Insect Diversity in a Mature Loblolly Pine Stand by Jessica Ahl A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Auburn, Alabama May 5, 2018 Keywords: Loblolly pine, hyperspectral interferometry, insect diversity Copyright 2019 by Jessica Ahl Approved by Dr. Lori Eckhardt, Chair, Professor of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences Dr. Ryan Nadel, Assistant Research Professor Dr. James Beach, CytoViva Director, Technology Department Dr. David Held, Associate Professor of Entomology Abstract Root-feeding beetles and weevils are known vectors of ophiostomatoid fungi, such as Leptographium and Grosmannia, that have been associated with a phenomenon called Southern Pine Decline in the Southeastern United States. One of these fungi, species name Leptographium terebrantis, has a well-known effect on pine seedlings, but the effect on mature, field-grown trees and associated insect populations is still to be determined. This study examined changes in insect diversity one year pre- and post-inoculation of mature loblolly pine trees with varying levels of a L. terebrantis isolate, giving special attention to monitoring insects of concern. Three different insect traps of two types – pitfall and airborne – were used during the twenty-five month study. Insects were collected every two weeks, identified to family where possible, and further sorted to morphospecies. Of 9,748 insects collected, we identified 16 orders, 149 families, and a total of 676 morphospecies. Of these, less than ten individuals were each Hylastes, Hylobiini, and Ips species of concern. We collected over 60 individual ambrosia beetles in nine species. -

Alien Invasive Species and International Trade

Forest Research Institute Alien Invasive Species and International Trade Edited by Hugh Evans and Tomasz Oszako Warsaw 2007 Reviewers: Steve Woodward (University of Aberdeen, School of Biological Sciences, Scotland, UK) François Lefort (University of Applied Science in Lullier, Switzerland) © Copyright by Forest Research Institute, Warsaw 2007 ISBN 978-83-87647-64-3 Description of photographs on the covers: Alder decline in Poland – T. Oszako, Forest Research Institute, Poland ALB Brighton – Forest Research, UK; Anoplophora exit hole (example of wood packaging pathway) – R. Burgess, Forestry Commission, UK Cameraria adult Brussels – P. Roose, Belgium; Cameraria damage medium view – Forest Research, UK; other photographs description inside articles – see Belbahri et al. Language Editor: James Richards Layout: Gra¿yna Szujecka Print: Sowa–Print on Demand www.sowadruk.pl, phone: +48 022 431 81 40 Instytut Badawczy Leœnictwa 05-090 Raszyn, ul. Braci Leœnej 3, phone [+48 22] 715 06 16 e-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Introduction .......................................6 Part I – EXTENDED ABSTRACTS Thomas Jung, Marla Downing, Markus Blaschke, Thomas Vernon Phytophthora root and collar rot of alders caused by the invasive Phytophthora alni: actual distribution, pathways, and modeled potential distribution in Bavaria ......................10 Tomasz Oszako, Leszek B. Orlikowski, Aleksandra Trzewik, Teresa Orlikowska Studies on the occurrence of Phytophthora ramorum in nurseries, forest stands and garden centers ..........................19 Lassaad Belbahri, Eduardo Moralejo, Gautier Calmin, François Lefort, Jose A. Garcia, Enrique Descals Reports of Phytophthora hedraiandra on Viburnum tinus and Rhododendron catawbiense in Spain ..................26 Leszek B. Orlikowski, Tomasz Oszako The influence of nursery-cultivated plants, as well as cereals, legumes and crucifers, on selected species of Phytophthopra ............30 Lassaad Belbahri, Gautier Calmin, Tomasz Oszako, Eduardo Moralejo, Jose A. -

Fossil History of Curculionoidea (Coleoptera) from the Paleogene

geosciences Review Fossil History of Curculionoidea (Coleoptera) from the Paleogene Andrei A. Legalov 1,2 1 Institute of Systematics and Ecology of Animals, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Ulitsa Frunze, 11, 630091 Novosibirsk, Novosibirsk Oblast, Russia; [email protected]; Tel.: +7-9139471413 2 Biological Institute, Tomsk State University, Lenin Ave, 36, 634050 Tomsk, Tomsk Oblast, Russia Received: 23 June 2020; Accepted: 4 September 2020; Published: 6 September 2020 Abstract: Currently, some 564 species of Curculionoidea from nine families (Nemonychidae—4, Anthribidae—33, Ithyceridae—3, Belidae—9, Rhynchitidae—41, Attelabidae—3, Brentidae—47, Curculionidae—384, Platypodidae—2, Scolytidae—37) are known from the Paleogene. Twenty-seven species are found in the Paleocene, 442 in the Eocene and 94 in the Oligocene. The greatest diversity of Curculionoidea is described from the Eocene of Europe and North America. The richest faunas are known from Eocene localities, Florissant (177 species), Baltic amber (124 species) and Green River formation (75 species). The family Curculionidae dominates in all Paleogene localities. Weevil species associated with herbaceous vegetation are present in most localities since the middle Paleocene. A list of Curculionoidea species and their distribution by location is presented. Keywords: Coleoptera; Curculionoidea; fossil weevil; faunal structure; Paleocene; Eocene; Oligocene 1. Introduction Research into the biodiversity of the past is very important for understanding the development of life on our planet. Insects are one of the Main components of both extinct and recent ecosystems. Coleoptera occupied a special place in the terrestrial animal biotas of the Mesozoic and Cenozoics, as they are characterized by not only great diversity but also by their ecological specialization. -

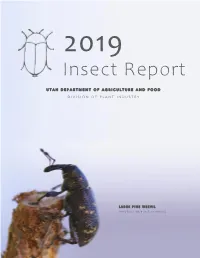

2019 UDAF Insect Report

2019 Insect Report UTAH DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND FOOD DIVISION OF PLANT INDUSTRY LARGE PINE WEEVIL H y l o b i u s a b i e ti s ( L i n n a e u s ) PROGRAM 2019 PARTNERS Insect Report MORMON CRICKET - VELVET LONGHORNED BEETLE - EMERALD ASH BORER - NUN MOTH - JAPANESE BEE- TLE - PINE SHOOT BEETLE - APPLE MAGGOT - GYPSY MOTH - PLUM CURCULIO - CHERRY FRUIT FLY - LARGE PINE WEEVIL - LIGHT BROWN APPLE MOTH - ROSY GYPSY MOTH - EUROPEAN HONEY BEE - BLACK FIR SAW- YER - GRASSHOPPER - MEDITERRANEAN PINE ENGRAVER - SIX-TOOTHED BARK BEETLE - NUN MOTH - EU- ROPEAN GRAPEVINE MOTH - SIBERIAN SILK MOTH - PINE TREE LAPPET - MORMON CRICKET - VELVET LONGHORNED BEETLE - EMERALD ASH BORER - NUN MOTH - JAPANESE BEETLE - PINE SHOOT BEETLE - AP- PLE MAGGOT - GYPSY MOTH - PLUM CURCULIO - CHERRY FRUIT FLY - LARGE PINE WEEVIL - LIGHT BROWN APPLE MOTH - ROSY GYPSY MOTH - EUROPEAN HONEY BEE - BLACK FIR SAWYER - GRASSHOPPER - MEDI- TERRANEAN PINE ENGRAVER - SIX-TOOTHED BARK BEETLE - NUN MOTH - EUROPEAN GRAPEVINE MOTH - SIBERIAN SILK MOTH - PINE TREE LAPPET - MORMON CRICKET - VELVET LONGHORNED BEETLE - EMERALD ASH BORER - NUN MOTH - JAPANESE BEETLE - PINE SHOOT BEETLE - APPLE MAGGOT - GYPSY MOTH - PLUM CURCULIO - CHERRY FRUIT FLY - LARGE PINE WEEVIL - LIGHT BROWN APPLE MOTH - ROSY GYPSY MOTH - EUROPEAN HONEY BEE - BLACK FIR SAWYER - GRASSHOPPER - MEDITERRANEAN PINE ENGRAVER - SIX-TOOTHED BARK BEETLE - NUN MOTH - EUROPEAN GRAPEVINE MOTH - SIBERIAN SILK MOTH - PINE TREE LAPPET - MORMON CRICKET - VELVET LONGHORNED BEETLE - EMERALD ASH BORER - NUN MOTH - JAPANESE -

Ethanol and (–)-A-Pinene: Attractant Kairomones for Some Large Wood-Boring Beetles in Southeastern USA

J Chem Ecol (2006) DOI 10.1007/s10886-006-9037-8 Ethanol and (–)-a-Pinene: Attractant Kairomones for Some Large Wood-Boring Beetles in Southeastern USA Daniel R. Miller Received: 12 September 2005 /Revised: 12 December 2005 /Accepted: 2 January 2006 # Springer Science + Business Media, Inc. 2006 Abstract Ethanol and a-pinene were tested as attractants for large wood-boring pine beetles in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina in 2002–2004. Multiple-funnel traps baited with (j)-a-pinene (released at about 2 g/d at 25–28-C) were attractive to the following Cerambycidae: Acanthocinus nodosus, A. obsoletus, Arhopalus rusticus nubilus, Asemum striatum, Monochamus titillator, Prionus pocularis, Xylotrechus integer, and X. sagittatus sagittatus. Buprestis lineata (Buprestidae), Alaus myops (Elateridae), and Hylobius pales and Pachylobius picivorus (Curculionidae) were also attracted to traps baited with (j)-a-pinene. In many locations, ethanol synergized attraction of the cerambycids Acanthocinus nodosus, A. obsoletus, Arhopalus r. nubilus, Monochamus titillator, and Xylotrechus s. sagittatus (but not Asemum striatum, Prionus pocularis,orXylotrechus integer)to traps baited with (j)-a-pinene. Similarly, attraction of Alaus myops, Hylobius pales, and Pachylobius picivorus (but not Buprestis lineata) to traps baited with (j)-a- pinene was synergized by ethanol. These results provide support for the use of traps baited with ethanol and (j)-a-pinene to detect and monitor common large wood- boring beetles from the southeastern region of the USA at ports-of-entry in other countries, as well as forested areas in the USA. Keywords Cerambycidae . Xylotrechus . Monochamus . Acanthocinus Curculionidae . Hylobius . Pachylobius . Elateridae . Alaus . Ethanol a-Pinene . -

25Th U.S. Department of Agriculture Interagency Research Forum On

US Department of Agriculture Forest FHTET- 2014-01 Service December 2014 On the cover Vincent D’Amico for providing the cover artwork, “…and uphill both ways” CAUTION: PESTICIDES Pesticide Precautionary Statement This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife--if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides and pesticide containers. Product Disclaimer Reference herein to any specific commercial products, processes, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recom- mendation, or favoring by the United States government. The views and opinions of wuthors expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the United States government, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. -

Identified Difficulties and Conditions for Field Success of Biocontrol

Identified difficulties and conditions for field success of biocontrol. 4. Socio-economic aspects: market analysis and outlook Bernard Blum, Philippe C. Nicot, Jürgen Köhl, Michelina Ruocco To cite this version: Bernard Blum, Philippe C. Nicot, Jürgen Köhl, Michelina Ruocco. Identified difficulties and conditions for field success of biocontrol. 4. Socio-economic aspects: market analysis and outlook. Classical and augmentative biological control against diseases and pests: critical status analysis and review of factors influencing their success, IOBC - International Organisation for Biological and Integrated Controlof Noxious Animals and Plants, 2011, 978-92-9067-243-2. hal-02809583 HAL Id: hal-02809583 https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02809583 Submitted on 6 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. WPRS International Organisation for Biological and Integrated Control of Noxious IOBC Animals and Plants: West Palaearctic Regional Section SROP Organisation Internationale de Lutte Biologique et Integrée contre les Animaux et les OILB Plantes Nuisibles: -

Status and Development of Old-Growth Elements and Biodiversity During Secondary Succession of Unmanaged Temperate Forests

Status and development of old-growth elementsand biodiversity of old-growth and development Status during secondary succession of unmanaged temperate forests temperate unmanaged of succession secondary during Status and development of old-growth elements and biodiversity during secondary succession of unmanaged temperate forests Kris Vandekerkhove RESEARCH INSTITUTE NATURE AND FOREST Herman Teirlinckgebouw Havenlaan 88 bus 73 1000 Brussel RESEARCH INSTITUTE INBO.be NATURE AND FOREST Doctoraat KrisVDK.indd 1 29/08/2019 13:59 Auteurs: Vandekerkhove Kris Promotor: Prof. dr. ir. Kris Verheyen, Universiteit Gent, Faculteit Bio-ingenieurswetenschappen, Vakgroep Omgeving, Labo voor Bos en Natuur (ForNaLab) Uitgever: Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek Herman Teirlinckgebouw Havenlaan 88 bus 73 1000 Brussel Het INBO is het onafhankelijk onderzoeksinstituut van de Vlaamse overheid dat via toegepast wetenschappelijk onderzoek, data- en kennisontsluiting het biodiversiteits-beleid en -beheer onderbouwt en evalueert. e-mail: [email protected] Wijze van citeren: Vandekerkhove, K. (2019). Status and development of old-growth elements and biodiversity during secondary succession of unmanaged temperate forests. Doctoraatsscriptie 2019(1). Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek, Brussel. D/2019/3241/257 Doctoraatsscriptie 2019(1). ISBN: 978-90-403-0407-1 DOI: doi.org/10.21436/inbot.16854921 Verantwoordelijke uitgever: Maurice Hoffmann Foto cover: Grote hoeveelheden zwaar dood hout en monumentale bomen in het bosreservaat Joseph Zwaenepoel -

Pine Weevil (Hylobius Abietis)

Pine Weevil ( Hylobius abietis ) Feeding Pattern on Conifer Seedlings Frauke Fedderwitz 1, Niklas Björklund, Velemir Ninkovic, Göran Nordlander Department of Ecology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden. [email protected] Abstract The pine weevil ( Hylobius abietis ) is one of the most important forest pests in Europe, yet there is very little known about its detailed feeding behaviour. We study the temporal feeding pattern of individual pine weevils of both sexes for 24 hours with two treatments, intact and girdled seedlings. Properties of a meal, such as feeding duration, size and ingestion rate are of particular interest. The shortest interval considered to separate one feeding bout from another, the meal criterion, has never been published and it is only available for a few other insect species. Video recordings are analysed for feeding behaviour (e.g. duration of feeding activity, interval length between feeding activities, movements between and within feeding scars). We measured general activity patterns as there is insufficient knowledge on the daily behavioural patterns. We thereby got an in-depth view of the pine weevil feeding activity that would otherwise be difficult to assess. Introduction Herbivorous insects reduce the fitness of plants directly and indirectly by feeding despite inducing plant defence systems against herbivory [1]. Trees have especially low defence and tolerance as seedlings in comparison to other phases in plant ontogeny except for over-mature and senile plants [2]. The pine weevil ( Hylobius abietis ) is economically one of the most important forest pests in Europe [3]. Adults feed on the stem bark of conifer seedlings [4] and can cause seedling mortality of up to 90 % in the first three years [5]. -

Weevils) of the George Washington Memorial Parkway, Virginia

September 2020 The Maryland Entomologist Volume 7, Number 4 The Maryland Entomologist 7(4):43–62 The Curculionoidea (Weevils) of the George Washington Memorial Parkway, Virginia Brent W. Steury1*, Robert S. Anderson2, and Arthur V. Evans3 1U.S. National Park Service, 700 George Washington Memorial Parkway, Turkey Run Park Headquarters, McLean, Virginia 22101; [email protected] *Corresponding author 2The Beaty Centre for Species Discovery, Research and Collection Division, Canadian Museum of Nature, PO Box 3443, Station D, Ottawa, ON. K1P 6P4, CANADA;[email protected] 3Department of Recent Invertebrates, Virginia Museum of Natural History, 21 Starling Avenue, Martinsville, Virginia 24112; [email protected] ABSTRACT: One-hundred thirty-five taxa (130 identified to species), in at least 97 genera, of weevils (superfamily Curculionoidea) were documented during a 21-year field survey (1998–2018) of the George Washington Memorial Parkway national park site that spans parts of Fairfax and Arlington Counties in Virginia. Twenty-three species documented from the parkway are first records for the state. Of the nine capture methods used during the survey, Malaise traps were the most successful. Periods of adult activity, based on dates of capture, are given for each species. Relative abundance is noted for each species based on the number of captures. Sixteen species adventive to North America are documented from the parkway, including three species documented for the first time in the state. Range extensions are documented for two species. Images of five species new to Virginia are provided. Keywords: beetles, biodiversity, Malaise traps, national parks, new state records, Potomac Gorge. INTRODUCTION This study provides a preliminary list of the weevils of the superfamily Curculionoidea within the George Washington Memorial Parkway (GWMP) national park site in northern Virginia. -

Control and Management of the Pine Weevil Hylobius Abietis L

Control and Management of the Pine Weevil Hylobius abietis L. * Amelia TUDORAN , Ion OLTEAN, Mircea VARGA Department of Plants Protection, University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Cluj- Napoca,* Romania corresponding author: [email protected] BulletinUASVM Horticulture 76(1) / 2019 Print ISSN 1843-5254, Electronic ISSN 1843-5394 DOI:10.15835/buasvmcn-hort: 2018.0049 Abstract Hylobius abietis H. abietis in The pine weevil, L., is a pest of economic importance causing massive damage to conifer seedlings planted on reforestation sites. The lack of effective methods to prevent establishment of newly-harvested sites makes it a threat to European forests. The biology and ecology of the pine weevil have been intensely studied through the years. However, in light of current and future climate change much of the knowledge gathered thus far may need to be re-evaluated under these new conditions. Changes in temperature and other climatic variables may strongly change, for example, the development of the weevil and its distribution. Such changes may result in higher population numbers and increase the feeding pressure on newly planted seedlings,H. abietis thus making it a novel pest in certain areas or increasing its pest status in others. There is a need to synthesize our current understanding on the biology, behavior and methods of damage control by the pine weevil , in order to identify knowledge gaps and propose new management practices. In this review, we present such an overview and provide several examples on how this knowledge could be expanded or used to meet future challenges.Keywords Hylobius abietis, : Control, monitoring, prevention Introduction Hylobius abietis is considered to be the main Hylobius th decade (Olenici, and Olenici, 1994).