Factors Affecting the Goldcrest/Firecrest Abundance Ratio in Their Area of Sympatry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geographic and Individual Variation in Carotenoid Coloration in Golden-Crowned Kinglets (Regulus Satrapa)

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2009 Geographic and individual variation in carotenoid coloration in golden-crowned kinglets (Regulus satrapa) Celia Chui University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Chui, Celia, "Geographic and individual variation in carotenoid coloration in golden-crowned kinglets (Regulus satrapa)" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 280. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/280 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. GEOGRAPHIC AND INDIVIDUAL VARIATION IN CAROTENOID COLORATION IN GOLDEN-CROWNED KINGLETS ( REGULUS SATRAPA ) by Celia Kwok See Chui A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through Biological Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2009 © 2009 Celia Kwok See Chui Geographic and individual variation in carotenoid coloration in golden-crowned kinglets (Regulus satrapa ) by Celia Kwok See Chui APPROVED BY: ______________________________________________ Dr. -

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Estimating Numbers of Embryonic Lethals in Conifers

Heredity 69(1992)308—314 Received 26 November 1991 OThe Genetical Society of Great Britain Estimating numbers of embryonic lethals in conifers OUTI SAVOLAINEN, KATRI KARKKAINEN & HELMI KUITTINEN* Department of Genetics, University of Oulu, Oulu, Fin/and and *Department of Genetics, University of Helsinki, He/sink,, Fin/and Conifershave recessive lethal genes that eliminate most selfed embryos during seed development. It has been estimated that Scots pine has, on average, nine recessive lethals which act during seed development. Such high numbers are not consistent with the level of outcrossing, about 0.9—0.95, which has been observed in natural populations. Correcting for environmental mortality or using partial selfings provides significantly lower estimates of lethals. A similar discordance with numbers of lethals and observed outcrossing rates is true for other species. Keywords:embryoniclethals, inbreeding depression, outcrossing, Pinus sylvestris, Picea omorika. Introduction Reproduction system of conifers Conifershave no self-incompatibility mechanisms but Theproportion of self-pollination in conifers is early-acting inbreeding depression eliminates selfed variable. Sarvas (1962) suggested an average of 26 per embryos before seed maturation (Sarvas, 1962; cent for Pinus sylvestris, while Koski (1970) estimated Hagman & Mikkola, 1963). A genetic model for this values of self-fertilization around 10 per cent. The inbreeding depression has been developed by Koski genera Pinus and Picea have polyzygotic poly- (1971) and Bramlett & Popham (1971). Koski (1971, embryony, i.e. the ovules contain several archegonia. In 1973) has estimated that Pinus sylvestris and Picea Pinus sylvestris, the most common number of arche- abies have on average nine and 10 recessive lethals, gonia is two but it can range from one to five. -

SILVER BIRCH (BETULA PENDULA) at 200-230°C Raimo Alkn Risto Kotilainen

THERMAL BEHAVIOR OF SCOTS PINE (PINUS SYLVESTRIS) AND SILVER BIRCH (BETULA PENDULA) AT 200-230°C Postgraduate Student Raimo Alkn Professor and Risto Kotilainen Postgraduate Student Department of Chemistry, Laboratory of Applied Chemistry University of Jyvaskyla, PO. Box 35, FIN-40351 Jyvaskyla, Finland (Received April 1998) ABSTRACT Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and silver birch (Betuln pendula) were heated for 4-8 h in a steam atmosphere at low temperatures (200-230°C). The birch feedstock decomposed slightly more exten- sively (6.4-10.2 and 13515.2% of the initial DS at 200°C and 225"C, respectively) than the pine feedstock (5.7-7.0 and 11.1-15.2% at 205°C and 230°C. respectively). The results indicated that the differences in mass loss between these feedstocks were due to mainly the fact that carbohydrates (cellulose and hemicelluloses) were more amenable to various degradation reactions than lignin in intact wood. The degradation reactions were also monitored in both cases by determining changes in the elemental composition of the heat-treated products. Keywords: Heat treatment, carbohydrates, lignin, extractives, Pinus sylvestris, Betula pendula. INTRODUCTION content of hemicelluloses (25-30% of DS) In our previous experiments (AlCn et al. than hardwood (lignin and hemicelluloses are 2000), the thermal degradation of the structur- usually in the range 20-25 and 30-35% of al constituents (lignin and polysaccharides, DS, respectively). On the basis of these facts, i.e., cellulose and hemicelluloses) of Norway the thermal behavior of softwood and hard- spruce (Picea abies) was established under wood can be expected to be different, even at conditions (temperature range 180-225"C, low temperatures. -

Examensarbete I Ämnet Biologi

Examensarbete 2012:10 i ämnet biologi Comparison of bird communities in stands of introduced lodgepole pine and native Scots pine in Sweden Arvid Alm Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Fakulteten för skogsvetenskap Institutionen för vilt, fisk och miljö Examensarbete i biologi, 15 hp, G2E Umeå 2012 Examensarbete 2012:10 i ämnet biologi Comparison of bird communities in stands of introduced lodgepole pine and native Scots pine in Sweden Jämförelse mellan fågelsamhällen i bestånd av introducerad contortatall och inhemsk tall i Sverige Arvid Alm Keywords: Boreal forest, Pinus contorta, Pinus sylvestris, bird assemblage, Muscicapa striata Handledare: Jean-Michel Roberge & Adriaan de Jong 15 hp, G2E Examinator: Lars Edenius Kurskod EX0571 SLU, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Fakulteten för skogsvetenskap Faculty of Forestry Institutionen för vilt, fisk och miljö Dept. of Wildlife, Fish, and Environmental Studies Umeå 2012 Abstract The introduced lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) occupies more than 650 000 hectares in Sweden. There are some differences between lodgepole pine and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) forests which could affect bird assemblages, for example differences in canopy density and ground vegetation. Birds were surveyed in 14 localities in northern Sweden, each characterized by one middle-aged stand of lodgepole pine next to a stand of Scots pine. The two paired stands in each locality were planted by the forestry company SCA at the same time and in similar environment to evaluate the potential of lodgepole pine in Sweden. In those 14 localities, one to three point count stations were established in both the lodgepole pine and the Scots pine stand, depending on the size of the area. -

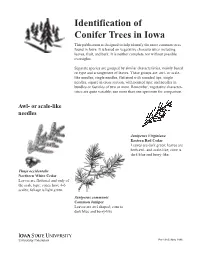

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to Identify the Level of Threat to Plants

Ex-Situ Conservation at Scott Arboretum Public gardens and arboreta are more than just pretty places. They serve as an insurance policy for the future through their well managed ex situ collections. Ex situ conservation focuses on safeguarding species by keeping them in places such as seed banks or living collections. In situ means "on site", so in situ conservation is the conservation of species diversity within normal and natural habitats and ecosystems. The Scott Arboretum is a member of Botanical Gardens Conservation International (BGCI), which works with botanic gardens around the world and other conservation partners to secure plant diversity for the benefit of people and the planet. The aim of BGCI is to ensure that threatened species are secure in botanic garden collections as an insurance policy against loss in the wild. Their work encompasses supporting botanic garden development where this is needed and addressing capacity building needs. They support ex situ conservation for priority species, with a focus on linking ex situ conservation with species conservation in natural habitats and they work with botanic gardens on the development and implementation of habitat restoration and education projects. BGCI uses the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to identify the level of threat to plants. In-depth analyses of the data contained in the IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, Red List are published periodically (usually at least once every four years). The results from the analysis of the data contained in the 2008 update of the IUCN Red List are published in The 2008 Review of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; see www.iucn.org/redlist for further details. -

Apparent Hybridisation of Firecrest and Goldcrest F

Apparent hybridisation of Firecrest and Goldcrest F. K. Cobb From 20th to 29th June 1974, a male Firecrest Regulus ignicapillus was seen regularly, singing strongly but evidently without a mate, in a wood in east Suffolk. The area had not been visited for some time before 20th June, so that it is not known how long he had been present. The wood covers some 10 ha and is mainly deciduous, com prised of oaks Quercus robur, sycamores Acer pseudoplatanus, and silver birches Betula pendula; there is also, however, a scatter of European larches Larix decidua and Scots pines Pinus sylvestris, with an occasional Norway spruce Picea abies. Apart from the silver birches, most are mature trees. The Firecrest sang usually from any one of about a dozen Scots pines scattered over half to three-quarters of a hectare. There was also a single Norway spruce some 18-20 metres high in this area, which was sometimes used as a song post, but the bird showed no preference for it over the Scots pines. He fed mainly in the surround ing deciduous trees, but was never heard to sing from them. The possibility of an incubating female was considered, but, as the male showed no preference for any particular tree, this was thought unlikely. Then, on 30th June, G. J. Jobson saw the Firecrest with another Regulus in the Norway spruce and, later that day, D. J. Pearson and J. G. Rolfe watched this second bird carrying a feather in the same tree. No one obtained good views of it, but, not unnaturally, all assumed that it was a female Firecrest. -

Lot # Item Description 1 12" Cased Ruby Flame Crest Bowl W/Double

Lot # Item description 1 12" Cased Ruby Flame Crest Bowl w/double crimp 2 8" Dave Fetty Hanging Hearts Hat 3 Blue Spiral Optic Water Set - pitcher & 5 tumblers have cobalt handles, 4 tumblers, 4 coasters, 9 stirrers 4 11" Mulberry Hand Vase 5 x2 4" Mini Vases - Beaded Melon Goldenrod & Mandarin Red Hobnail - x2 6 x2 Ebony Crest Fan Vase & Apple Blossom Crest Heart Dish - x2 7 x2 French Opal Basketweave Bowl & Crystal Cigarette Box/Silver Tray - x2 8 Cobalt Hanging Heart Egg 9 OOAK Aqua Crest Ewer w/Ruby Handle - whimsey 10 Tie Dye Happy Cat & Happy Kitty 11 Charleton Hat Vase w/enameled roses 12 2 Ruby Dolphin Candlesticks 13 Spring Pink Nymph w/frog & bowl 14 White Satin Working Elephant w/open trunk 15 Ruby Lincoln Inn Creamer & Sugar 16 Mongolian Green Lily of the Valley Bell 17 x2 Crystal Satin Verlys Lovebird Vase & Cobalt Console Bowl - x2 18 x2 Wild Rose Jacqueline Vase & Cranberry Opal Spiral Optic Vase - x2 19 Set of 4 Ruby Jay-Cee Etched Plates Circa 1930-1955 20 3 Piece Fairy Light - Ruby Stretch Sample w/Sunflowers hp by Frances Burton 21 9.5" Covered Footed Candy Dish #2/8 2016 Penguins by Frances Burton 22 15" Amphora w/brass stand #5/6 2016 Woodpecker by JK Spindler 23 9" Rosalene Basket Glass Legacy 95 Years by Pam Hayhurst 24 10" Nouveau Blue Satin Overlay Vase 8 Family Signatures by S Waters 25 9"Milk Ruby Overlay Satin Vase w/sunflower 9 Family Signature by CC Hardman 26 Opal Halloween Alley Cat #5/20 2016 by Kim Barley 27 Jadeite Alley Cat w/Bluebird Nest #1/7 2016 by M Kibbe 28 Ringneck Drake & Duck Mallard Set 2016 -

{PDF} Notebook : Goldcrest Bird Small Birds Gold Crest Kindle

NOTEBOOK : GOLDCREST BIRD SMALL BIRDS GOLD CREST Author: Wild Pages Press Number of Pages: 150 pages Published Date: 12 Dec 2019 Publisher: Independently Published Publication Country: none Language: English ISBN: 9781674550428 DOWNLOAD: NOTEBOOK : GOLDCREST BIRD SMALL BIRDS GOLD CREST Notebook : Goldcrest Bird Small Birds Gold Crest PDF Book " NORMAN CAMERON, Ph. If you want debt help on a budget - with straight talk and no tricks - you'll find everything you need right here. MyITLab builds the critical skills needed for college and career success. Purchase CompTIA A TODAY. A Short History of Roman LawTort Law provides a different approach to the study of tort. Plus, you'll find over 70 practical exercises to help you evaluate your writing to the breakout level. The goal of this education was that, through living inner work guided by the insights of Rudolf Steiner, the teachers would develop in the children such power of thought, depth of feeling, and strength of will that they would emerge from their school years as full members of the human community, able to meet and transform the world. sagepub. It aims to meet the requirements of the new national curriculum for English at KS2 in a way that will develop the children's standard of writing by presenting activities that they will find enjoyable and stimulating. ' - Care and Health Magazine 'The poems show the human side of care and are essential reading for those who wish to be critically reflective about the nature of care and their own insight within the caring process. How small green choices can have a big impact. -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Myanmar

Avibase Page 1of 30 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Myanmar 2 Number of species: 1088 3 Number of endemics: 5 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of introduced species: 1 6 7 8 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Myanmar. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=mm [23/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Pinus Sylvestris Breeding for Resistance Against Natural Infection of the Fungus Heterobasidion Annosum

Article Pinus sylvestris Breeding for Resistance against Natural Infection of the Fungus Heterobasidion annosum 1 1, 2 1 Raitis Rieksts-Riekstin, š , Pauls Zeltin, š * , Virgilijus Baliuckas , Lauma Bruna¯ , 1 1 Astra Zal, uma and Rolands Kapostin¯ , š 1 Latvian State Forest Research Institute Silava, 111 Rigas street, LV-2169 Salaspils, Latvia; [email protected] (R.R.-R.); [email protected] (L.B.); [email protected] (A.Z.); [email protected] (R.K.) 2 Forest Institute, Lithuanian Centre for Agriculture and Forestry, Department of Forest Tree Genetics and Breeding, Liepu St. 1, Girionys, LT-53101 Kaunas distr., Lithuania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 November 2019; Accepted: 19 December 2019; Published: 22 December 2019 Abstract: Increasing resistance against biotic and abiotic factors is an important goal of forest tree breeding. The aim of the present study was to develop a root rot resistance index for Scots pine breeding and evaluate its effectiveness. The productivity, branch diameter, branchiness, stem straightness, spike knots, and damage from natural infection of root rot in 154 Scots pine open-pollinated families from Latvia were evaluated through a progeny field trial at the age of 38 years. Trees with decline symptoms were sampled for fungal isolations. Based on this information and kriging estimates of root rot, 35 affected areas (average size: 108 m2; total 28% from the 1.5 ha trial) were delineated. Resistance index of a single tree was formed based on family adjusted proportion of live to infected trees and distance to the center of affected area.