A Geometric Analysis of Surface Deformation: Implications for the Tectonic Evolution of Ganymede

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUICE Red Book

ESA/SRE(2014)1 September 2014 JUICE JUpiter ICy moons Explorer Exploring the emergence of habitable worlds around gas giants Definition Study Report European Space Agency 1 This page left intentionally blank 2 Mission Description Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer Key science goals The emergence of habitable worlds around gas giants Characterise Ganymede, Europa and Callisto as planetary objects and potential habitats Explore the Jupiter system as an archetype for gas giants Payload Ten instruments Laser Altimeter Radio Science Experiment Ice Penetrating Radar Visible-Infrared Hyperspectral Imaging Spectrometer Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph Imaging System Magnetometer Particle Package Submillimetre Wave Instrument Radio and Plasma Wave Instrument Overall mission profile 06/2022 - Launch by Ariane-5 ECA + EVEE Cruise 01/2030 - Jupiter orbit insertion Jupiter tour Transfer to Callisto (11 months) Europa phase: 2 Europa and 3 Callisto flybys (1 month) Jupiter High Latitude Phase: 9 Callisto flybys (9 months) Transfer to Ganymede (11 months) 09/2032 – Ganymede orbit insertion Ganymede tour Elliptical and high altitude circular phases (5 months) Low altitude (500 km) circular orbit (4 months) 06/2033 – End of nominal mission Spacecraft 3-axis stabilised Power: solar panels: ~900 W HGA: ~3 m, body fixed X and Ka bands Downlink ≥ 1.4 Gbit/day High Δv capability (2700 m/s) Radiation tolerance: 50 krad at equipment level Dry mass: ~1800 kg Ground TM stations ESTRAC network Key mission drivers Radiation tolerance and technology Power budget and solar arrays challenges Mass budget Responsibilities ESA: manufacturing, launch, operations of the spacecraft and data archiving PI Teams: science payload provision, operations, and data analysis 3 Foreword The JUICE (JUpiter ICy moon Explorer) mission, selected by ESA in May 2012 to be the first large mission within the Cosmic Vision Program 2015–2025, will provide the most comprehensive exploration to date of the Jovian system in all its complexity, with particular emphasis on Ganymede as a planetary body and potential habitat. -

High-Resolution Mosaics of the Galilean Satellites from Galileo SSI

Lunar and Planetary Science XXIX 1833.pdf High-Resolution Mosaics of the Galilean Satellites from Galileo SSI. M. Milazzo, A. McEwen, C. B. Phillips, N. Dieter, J. Plassmann. Planetary Image Research Laboratory, LPL, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721; [email protected] The Galileo Spacecraft began mapping the Jovian orthographic projection centered at the latitude and system in June 1996. Twelve orbits of Jupiter and more longitude coordinates of the sub-spacecraft point to than 1000 images later, the Solid State Imager (SSI) is still preserve their perspective. Depending on the photometric collecting images, most far superior in resolution to geometry and scale, it may be necessary to apply a anything collected by the Voyager spacecraft. The data photometric normalization to the images. Next, the collected includes: low to medium resolution color data, individual frames are mosaicked together, and mosaicked medium resolution data to fill gaps in Voyager coverage, and onto a portion of the base map for regional context. Once very high-resolution data over selected areas. We have the mosaic is finished, it is checked to make sure that the tie been systematically processing the SSI images of the and match points were correct, and that the frames mesh. Galilean satellites to produce high-resolution mosaics and to We produce 3 final products: (i) an SSI-only mosaic, (ii) SSI place them into the regional context provided by medium- images mosaicked onto regional context, and (iii) the resolution mosaics from Voyager and/or Galileo. addition of a latitude-longitude grid to the context mosaic. Production of medium-resolution global mosaics is The purpose of this poster is to show the mosa- described in a companion abstract [1]. -

Appendix Contains a Timeline, Galileo Mission Overview (June 1996–December 1997), and a Set of Quick–Look Orbit Facts Sheets

A P P E N D I X This appendix contains a timeline, Galileo Mission Overview (June 1996–December 1997), and a set of Quick–Look Orbit Facts sheets. The essentials of each orbit are listed. We have provided them as a handy reference while the orbiter’s tour progresses in the months to come. Appendix • Page A-1 Project Galileo Quick-Look Orbit Facts Appendix • Page A- 5 PROJECT GALILEO QUICK-LOOK ORBIT FACTS Fact Sheet Guide Title Quick Facts Indicates the target satellite and the number of the This section provides a summary listing of the orbit in the satellite tour. In this example, Ganymede is characteristics of the target satellite encounter as well the target satellite on the first orbit of the orbital tour. as the Jupiter encounter. PROJECT GALILEO QUICK-LOOK ORBIT FACTS PROJECT GALILEO QUICK-LOOK ORBIT FACTS Ganymede - Orbit 1 Ganymede - Orbit 1 Encounter Trajectory Quick Facts Ganymede Flyby Geometry +30 min Ganymede Encounter Earth Sun 27 June 1996 Ganymede C/A +15 min 06:29 UTC Ganymede C/A Altitude: 844 km Jupiter 6/27 6/26 133 times closer than VGR1 70 times closer than VGR2 Earth Speed: 7.8 km/s 0W -15 min Sun Jupiter C/A 6/28 Latitude: 30 deg N Longitude: 112 deg W 270W -30 min Perijove Io 28 June 1996 00:31 UTC Europa Jupiter Range: 11.0 Rj Time Ordered Listing Ganymede 6/29 Earth Range: 4.2 AU EVENT TIME (PDT-SCET) EVENT (continued) TIME (PDT-SCET) OWLT: 35 min Start Encounter 23 June 96 09:00 Europa C/A (156000 km) 18:22 Callisto Start Ganymede-1 real-time survey (F&P) 09:02 Europa global observation (NIMS/SSI) 18:43 -

The Global Colors of Ganymede As Seen by Galileo Ssi

Lunar and Planetary Science XXX 1822.pdf THE GLOBAL COLORS OF GANYMEDE AS SEEN BY GALILEO SSI. T. Denk1, K.K. Khurana2, R.T. Pappalardo3, G. Neukum1, J.W. Head3, T.V. Rosanova4, and the Galileo SSI Team, 1DLR, Institute of Planetary Exploration, 12484 Berlin, Germany, e-mail: [email protected], 2UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, 3Brown University, Providence, RI, 4USGS, Flagstaff, AZ. Ganymede, as observed by the Galileo SSI Dark vs. bright and polar terrain. The bright camera, shows a banded, latitude-dependent color ("sulci") and dark ("regio") areas as well as the polar structure which is partly independent of geologic caps are the most obvious surface features on Ganyme- units. A correlation of the surface color with the de when seen at global scale from large distances. The magnetic field of Ganymede is reported, with areas albedo of the polar caps on the leading side is highest, exposed to the charged particles coming from the of the "regio" areas lowest, and of the "sulci" areas in Jovian environment often being redder than shielded between. (The polar caps of the trailing side will be terrain. The northern polar cap can be subdivided discussed below.) The bright polar caps are probably into a whitish area on the pole and the leading side, caused by water frost (e.g., Smith et al. 1981, Hillier and a darker, reddish area on the trailing side. The frost of the south-polar cap appears less opaque than in the north. The spectra of the dark "regio" areas are redder at the long SSI wavelength range than those of the brighter "sulci" terrains, but not significantly different at short SSI wavelengths. -

Radar Imaging of Solar System Ices

RADAR IMAGING OF SOLAR SYSTEM ICES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Leif J. Harcke May 2005 © Copyright by Leif J. Harcke 2005 All Rights Reserved ii iv Abstract We map the planet Mercury and Jupiter’s moons Ganymede and Callisto using Earth-based radar telescopes and find that all bodies have regions exhibiting high, depolarized radar backscatter and polarization inversion (µc > 1). Both characteristics suggest volume scat- tering from water ice or similar cold-trapped volatiles. Synthetic aperture radar mapping of Mercury’s north and south polar regions at fine (6 km) resolution at 3.5 cm wavelength corroborates the results of previous 13 cm investigations of enhanced backscatter and po- larization inversion (0:9 µc 1:3) from areas on the floors of craters at high latitudes, ≤ ≤ where Mercury’s near-zero obliquity results in permanent Sun shadows. Co-registration with Mariner 10 optical images demonstrates that this enhanced scattering cannot be caused by simple double-bounce geometries, since the bright, reflective regions do not appear on the radar-facing wall but, instead, in shadowed regions not directly aligned with the radar look direction. A simple scattering model accounts for exponential, wavelength-dependent attenuation through a protective regolith layer. Thermal models require the existence of this layer to protect ice deposits in craters at other than high polar latitudes. The additional attenuation (factor 1:64 15%) of the 3.5 cm wavelength data from these experiments over previous 13 cm radar observations supports multiple interpretations of layer thickness, ranging from 0 11 to 35 15 cm, depending on the assumed scattering law exponent n. -

The Origin of Ganymede's Polar Caps

Icarus 191 (2007) 193–202 www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus The origin of Ganymede’s polar caps Krishan K. Khurana a,∗, Robert T. Pappalardo b, Nate Murphy c, Tilmann Denk d a Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA b Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Dr., Pasadena, CA 91109, USA c Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0392, USA d Freie Universität Berlin, Institut für Geologische Wissenschaften, Malteserstraße 74-100, 12249 Berlin, Germany Received 7 August 2006; revised 13 April 2007 Available online 5 May 2007 Abstract Since their discovery in Voyager images, the origin of the bright polar caps of Ganymede has intrigued investigators. Some models attributed the polar cap formation to thermal migration of water vapor to higher latitudes, while other models implicated plasma bombardment in brightening ice. Only with the arrival of Galileo at Jupiter was it apparent that Ganymede possesses a strong internal magnetic field, which blocks most of the plasma from bombarding the satellite’s equatorial region while funneling plasma onto the polar regions. This discovery provides a plausible explanation for the polar caps as related to differences in plasma-induced brightening in the polar and the equatorial regions. In this context, we analyze global color and high resolution images of Ganymede obtained by Galileo, finding a very close correspondence between the observed polar cap boundary and the open/closed field lines boundary obtained from new modeling of the magnetic field environment. This establishes a clear link between plasma bombardment and polar cap brightening. -

Challenging the Paradigm: the Legacy of Galileo Symposium

Challenging the Paradigm: The Legacy of Galileo Symposium November 19, 2009 California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California Proceedings of the 2009 Symposium and Public Lecture Challenging the Paradigm: The Legacy of Galileo NOVEMBER 19, 2009 CAHILL BUILDING - HAMEETMAN AUDITORIUM CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY PASADENA, CALIFORNIA, USA © 2011 W. M. KECK INSTITUTE FOR SPACE STUDIES, ISBN-13: 978-1-60049-005-07 CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ISBN-10: 1-60049-005-0 Sponsored by The W.M. Keck Institute for Space Studies Supported by The Italian Consulate – Los Angeles The Italian Cultural Institute – Los Angeles Italian Scientists and Scholars in North America Foundation The Planetary Society Organizing Committee Dr. Cinzia Zuffada – Jet Propulsion Laboratory (Chair) Professor Mike Brown – California Institute of Technology (Co-Chair) Professor Giorgio Einaudi – Università di Pisa Dr. Rosaly Lopes – Jet Propulsion Laboratory Professor Jonathan Lunine - University of Arizona Dr. Marco Velli – Jet Propulsion Laboratory Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Galileo's New Paradigm: The Ultimate Inconvenient Truth…………………………... 3 Professor Alberto Righini University of Florence, Italy Galileo and His Times…………………………………………………………………….. 11 Professor George V. Coyne, S.J. Vatican Observatory The Galileo Mission: Exploring the Jovian System…………………………………….. 19 Dr. Torrence V. Johnson Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology What We Don't Know About Europa……………………………………………………. 33 Dr. Robert T. Pappalardo Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology The Saturn System as Seen from the Cassini Mission…………………………………. 55 Dr. Angioletta Coradini IFSI – Istituto di Fisica dello Spazio Interplanetario dell’INAF - Roma Solar Activity: From Galileo's Sunspots to the Heliosphere………………………….. 67 Professor Eugene N. Parker University of Chicago From Galileo to Hubble and Beyond - The Contributions and Future of the Telescope: The Galactic Perspective……………………………………………………. -

Modern Mars' Geomorphological Activity

Title: Modern Mars’ geomorphological activity, driven by wind, frost, and gravity Serina Diniega, Ali Bramson, Bonnie Buratti, Peter Buhler, Devon Burr, Matthew Chojnacki, Susan Conway, Colin Dundas, Candice Hansen, Alfred Mcewen, et al. To cite this version: Serina Diniega, Ali Bramson, Bonnie Buratti, Peter Buhler, Devon Burr, et al.. Title: Modern Mars’ geomorphological activity, driven by wind, frost, and gravity. Geomorphology, Elsevier, 2021, 380, pp.107627. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2021.107627. hal-03186543 HAL Id: hal-03186543 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03186543 Submitted on 31 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Title: Modern Mars’ geomorphological activity, driven by wind, frost, and gravity 2 3 Authors: Serina Diniega1,*, Ali M. Bramson2, Bonnie Buratti1, Peter Buhler3, Devon M. Burr4, 4 Matthew Chojnacki3, Susan J. Conway5, Colin M. Dundas6, Candice J. Hansen3, Alfred S. 5 McEwen7, Mathieu G. A. Lapôtre8, Joseph Levy9, Lauren Mc Keown10, Sylvain Piqueux1, 6 Ganna Portyankina11, Christy Swann12, Timothy N. Titus6, -

Gany 15Ppi.Pdf

180° 0° 55° –55° . Geb Ur Sulcus 210° 330° 150° . Latpon 30° 60° –60° . Namtar . Agrotes Elam Philae Sulcus Sulci . Nigirsu Borsip Sulcus Lakhmu Fossae 70° –70° 240° 300° 60° 120° Galileo . Humbaba . Lagamal 80° . Wepwawet –80° . Teshub 90° 270° 90° 270° . Hathor Regio Bubastis Sulci Anubis . Neheh Dukug Sulcus 80° –80° Anzu Hamra. Patera . Adapa Etana GILGAMESH . Kishar . Aya 120° 60° 300° 240° . Ptah –70° . 70° Isis Ninkasi . Anu Enlil . Zaqar . Gula . Tanit . Sapas . Achelous Sebek 60° –60° 30° 150° 330° Mummu Sulci 210° . Adad 55° –55° 0° 180° North Pole South Pole 180° 170° 160° 150° 140° 130° 120° 110° 100° 90° 80° 70° 60° 50° 40° 30° 20° 10° 0° 350° 340° 330° 320° 310° 300° 290° 280° 270° 260° 250° 240° 230° 220° 210° 200° 190° 180° 57° 57° Geb . Enlil Elam Sulci . Asshur . Sin Ur Sulcus 50° 50° Aquarius Sulcus . Kadi Nun Sulci . Hershef Mashu Sulcus . Upuant Lakhmu Fossae . Galileo . Nefertum Mont Ur . Shu Byblus Sulcus Nippur Sulcus Sulcus Philus Sulcus 40° Enki Catena 40° Zu Fossae Nergal . Akitu Sulcus Tettu Facula . Lumha . Harakhtes . Halieus Abydos . Gir . Perrine Regio Khnum . Amon Facula Regio Kulla Catena . Anhur . Marius Nippur Sulcus M . Ammura Zakar . 30° Sati Mor a Bigeh . s 30° . Mehit Min . h Akhmin Facula Haroeris u Neith . Sicyon Sulcus Ta-urt S Facula Edfu Xibalba Sulcus Nineveh Sulcus u Anshar Sulcus l c Facula u . Ba'al s Epigeus . Bau Diment . Lugalmeslam Epigeus . Ilah Atra-hasis Hermopolis . Facula 20° Khepri Gushkin 20° . Ea . Heliopolis . Geinos Nidaba Nanshe . Facula Memphis Catena Seima . Agreus Busiris Chrysor.. Aleyin . -

Linking Asteroids and Meteorites Through Reflectance Spectroscopy

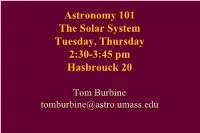

Astronomy 101 The Solar System Tuesday, Thursday 2:30-3:45 pm Hasbrouck 20 Tom Burbine [email protected] Course • Course Website: – http://blogs.umass.edu/astron101-tburbine/ • Textbook: – Pathways to Astronomy (2nd Edition) by Stephen Schneider and Thomas Arny. • You also will need a calculator. Office Hours • Mine • Tuesday, Thursday - 1:15-2:15pm • Lederle Graduate Research Tower C 632 • Neil • Tuesday, Thursday - 11 am-noon • Lederle Graduate Research Tower B 619-O Homework • We will use Spark • https://spark.oit.umass.edu/webct/logonDisplay.d owebct • Homework will be due approximately twice a week Class Averages • For people who took all 4 tests: • Class average is 81 • Grades range from a 98.5 to a 55.4 • Scores will go up when the lowest exam grade is dropped after the final • A (92.50 – 100) • A- (89.50 – 92.49) • B+ (87.50 – 89.49) • B (82.50 – 87.49) • B- (79.50 – 82.49) • C+ (77.50 – 79.49) • C (72.50 – 77.49) • C- (69.50 – 72.49) • D (59.50 – 69.49) • F (below 59.49) Final • Cumulative • Monday - 12/14 • 4:00 pm • Hasbrouck 20 • Review Session • Sunday -12/13 • 3:00 pm • Hasbrouck 134 Formulas you may need to know • p2 = a3 • F = GMm/r2 • F = ma • a = GM/r2 • Escape velocity = sqrt(2GM/r) • T (K) = T (oC) + 273.15 • c = f*λ • E = h*f • KE = 1/2mv2 • E = mc2 • Density = mass/volume • Volume = 4/3πr3 More Formulas • Power emitted per unit surface area = σT4 • λmax (nm) = (2,900,000 nm*K)/T • Apparent brightness = Luminosity 4π x (distance)2 Intelligent Life • Intelligent life that we can detect is usually defined as life that can build a radio telescope Radio • Transmitting information over radio waves is very cheap • uses equipment that is easy to build • has the information-carrying capacity necessary for the task • The information also travels at the speed of light. -

Surface Composition and Properties of Ganymede: Updates from Ground-Based Observations with the Near-Infrared

Surface composition and properties of Ganymede: updates from ground-based observations with the near-infrared imaging spectrometer SINFONI/VLT/ESO. Ligier N. 1, Paranicas C. 2, Carter J. 3, Poulet F. 3, Calvin W.M. 4, Nordheim T.A. 5, Snodgrass C. 1,6, Ferellec L. 3 1School of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK. 2Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University, Laurel, MD 20723, USA. 3Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, Université Paris-Saclay, 91405 Orsay Cedex, France. 4Geological Sciences & Engineering, University of Nevada, Reno, NV 89557, USA. 5Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA. 6School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 9YL, UK. First author’s e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Ganymede’s surface exhibits great geological diversity, with old dark terrains, expressed through the surface composition, which is known to be dominated by two constituents: H2O-ice and an unidentified darkening agent. In this paper, new investigations of the composition of Ganymede’s surface at global scale are presented. The analyses are derived from the linear spectral modeling of a high spectral resolution dataset, acquired with the near-infrared (1.40 – 2.50 µm) ground-based integral field spectrometer SINFONI (SINgle Faint Object Near-IR Investigation) of the Very Large Telescope (VLT hereafter) located in Chile. We show that, unlike the neighboring moon Europa, photometric corrections cannot be performed using a simple Lambertian model. However, we find that the Oren- Nayar (1994) model, generalizing the Lambert’s law for rough surfaces, produces excellent results. Spectral modeling confirms that Ganymede’s surface composition is dominated by H2O-ice, which is predominantly crystalline, as well as a darkening agent, but it also clearly highlights the necessity of secondary species to better fit the measurements: sulfuric acid hydrate and salts, likely sulfates and chlorinated. -

DARK HALO CRATERS and the THICKNESS of GROOVED TERRAIN on GANYMEDE, Paul M

DARK HALO CRATERS AND THE THICKNESS OF GROOVED TERRAIN ON GANYMEDE, Paul M. Schenk and William B. McKinnon, Dept. of Earth & Planetary Sciences, Washington University, St. Louis, MO. 63130. Dark halo craters in grooved terrain on Ganymede represent potential probes of the subsurface geology of Ganymede. Pamentier et al. (1) have suggested that bright grooved terrain may have formed by the flooding of gra- ben within older and darker cratered terrain. If the flooded material is thin enough, craters forming in it may have excavated darker cratered terrain material from below the bri'ghter grooved terrain unit, incorporating the dark material into its ejecta. As the bright ray and rim materials equilibrate with the space environment (approach the albedo of undisturbed grooved ter- rain), the darker material in the ejecta will remain as a darker albedo ejec- ta deposit; i .e., dark halo craters. The existence of a transition diameter between craters that do and do not excavate into the buried darker cratered terrain should therefore provide an estimate of the thickness of the flooded material, if this model is valid. We assume that the low albedo is not a photometric effect. Dark halo craters (DHC) are surrounded by broad, circular, low a1 bedo deposits interpreted here as ejecta (Fig. 1). As such, they are distinct from dark ray craters. Dark ray craters and those with bright deposits were not considered because of the ray deposits. DHCs have been identifiable in most large tracts of grooved terrain, %55% are concentrated within Uruk Sulcus, the zone of grooved terrain immediately southwest of Galileo Regio.