9. Metro Manila, Philippines Theresa Audrey O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Disasters in the Philippines: a Case Study of the Immediate Causes and Root Drivers From

Zhzh ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 Environment & Natural Resources Program Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org/ENRP The authors of this report invites use of this information for educational purposes, requiring only that the reproduced material clearly cite the full source: Franta, Benjamin, et al, “Climate disasters in the Philippines: A case study of immediate causes and root drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University, November 2016. Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: A destroyed church in Samar, Philippines, in the months following Typhoon Yolanda/ Haiyan. (Benjamin Franta) Copyright 2016, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 The Environment and Natural Resources Program (ENRP) The Environment and Natural Resources Program at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs is at the center of the Harvard Kennedy School’s research and outreach on public policy that affects global environment quality and natural resource management. -

Land Use Planning in Metro Manila and the Urban Fringe: Implications on the Land and Real Estate Market Marife Magno-Ballesteros DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Land Use Planning in Metro Manila and the Urban Fringe: Implications on the Land and Real Estate Market Marife Magno-Ballesteros DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2000-20 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are be- ing circulated in a limited number of cop- ies only for purposes of soliciting com- ments and suggestions for further refine- ments. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not neces- sarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. June 2000 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Staff, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 3rd Floor, NEDA sa Makati Building, 106 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City, Philippines Tel Nos: 8924059 and 8935705; Fax No: 8939589; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at http://www.pids.gov.ph TABLE of CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 1 2. The Urban Landscape: Metro Manila and its 2 Peripheral Areas The Physical Environment 2 Pattern of Urban Settlement 4 Pattern of Land Ownership 9 3. The Institutional Environment: Urban Management and Land Use Planning 11 The Historical Precedents 11 Government Efforts Toward Comprehensive 14 Urban Planning The Development Control Process: 17 Centralization vs. Decentralization 4. Institutional Arrangements: 28 Procedural Short-cuts and Relational Contracting Sources of Transaction Costs in the Urban 28 Real Estate Market Grease/Speed Money 33 Procedural Short-cuts 36 5. -

1 Introduction

Formulation of an Integrated River Basin Management and Development Master Plan for Marikina River Basin VOLUME 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION The Philippines, through RBCO-DENR had defined 20 major river basins spread all over the country. These basins are defined as major because of their importance, serving as lifeblood and driver of the economy of communities inside and outside the basins. One of these river basins is the Marikina River Basin (Figure 1). Figure 1 Marikina River Basin Map 1 | P a g e Formulation of an Integrated River Basin Management and Development Master Plan for Marikina River Basin VOLUME 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Marikina River Basin is currently not in its best of condition. Just like other river basins of the Philippines, MRB is faced with problems. These include: a) rapid urban development and rapid increase in population and the consequent excessive and indiscriminate discharge of pollutants and wastes which are; b) Improper land use management and increase in conflicts over land uses and allocation; c) Rapidly depleting water resources and consequent conflicts over water use and allocation; and e) lack of capacity and resources of stakeholders and responsible organizations to pursue appropriate developmental solutions. The consequence of the confluence of the above problems is the decline in the ability of the river basin to provide the goods and services it should ideally provide if it were in desirable state or condition. This is further specifically manifested in its lack of ability to provide the service of preventing or reducing floods in the lower catchments of the basin. There is rising trend in occurrence of floods, water pollution and water induced disasters within and in the lower catchments of the basin. -

PHILIPPINES Manila GLT Site Profile

PHILIPPINES Manila GLT Site Profile AZUSA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY GLOBAL LEARNING TERM 626.857.2753 | www.apu.edu/glt 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO MANILA ................................................... 3 GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................ 5 CLIMATE AND GEOGRAPHY .................................................... 5 DIET ............................................................................................ 5 MONEY ........................................................................................ 6 TRANSPORTATION ................................................................... 7 GETTING THERE ....................................................................... 7 VISA ............................................................................................. 8 IMMUNIZATIONS ...................................................................... 9 LANGUAGE LEARNING ............................................................. 9 HOST FAMILY .......................................................................... 10 EXCURSIONS ............................................................................ 10 VISITORS .................................................................................. 10 ACCOMODATIONS ................................................................... 11 SITE FACILITATOR- GLT PHILIPPINES ................................ 11 RESOURCES ............................................................................... 13 NOTE: Information is subject to -

Cities Development Initiative for Asia P R O J E C T O V E R V I E W

Cities Development Initiative for Asia P R O J E C T O V E R V I E W Country: P H I L I P P I N E S Status: Key Sector(s): COMPLETED FLOOD AND DRAINAGE MANAGEMENT City: VALENZUELA Application approved: 20/JAN/2014 P R O P O N E N T S Geography and Population Valenzuela City Government Mayor Rex Gatchalian Area: 44.59 km2 City Hall, MacArthur Highway, City Mayor Barangay Karuhatan, Valenzuela City, City Government of Valenzuela Population: 598,968 Metropolitan Manila 1400 The city of Valenzuela is located 14km north of Phone: (+63) 2 352 1000 Phone: (+63) 291 3069 Manila, the capital city of Website: www.valenzuela.gov.ph the Philippines. It is one of the 16 highly urbanized Central State Partner Other Partners cities of Metropolitant National Economic Development DPWH, Maynilad Manila. Due to its strategic Authority (NEDA) location at the northern K E Y C I T Y D E V E L O P M E N T I S S U E S most part of Metro Manila, and the migration of The overall city's development plans focus on the following areas: people, Valenzuela has Valenzuela is located in an area that has 16% frequency of tropical cyclones grown into a major also, a third of the city, particularly the western side is composed of swampy economic and industrial areas that are not only one to five meters above the sea level; this greatly center. makes the city particularly the improverished areas susceptible to flooding. -

Business Directory Commercial Name Business Address Contact No

Republic of the Philippines Muntinlupa City Business Permit and Licensing Office BUSINESS DIRECTORY COMMERCIAL NAME BUSINESS ADDRESS CONTACT NO. 12-SFI COMMODITIES INC. 5/F RICHVILLE CORP TOWER MBP ALABANG 8214862 158 BOUTIQUE (DESIGNER`S G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER AYALA ALABANG BOULEVARD) 158 DESIGNER`S BLVD G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER AYALA ALABANG 890-8034/0. EXTENSION 1902 SOFTWARE 15/F ASIAN STAR BUILDING ASEAN DRIVE CORNER DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION SINGAPURA LANE FCC ALABANG 3ARKITEKTURA INC KM 21 U-3A CAPRI CONDO WSR CUPANG 851-6275 7 MARCELS CLOTHING INC.- LEVEL 2 2040.1 & 2040.2 FESTIVAL SUPERMALL 8285250 VANS FESTIVAL ALABANG 7-ELEVEN RIZAL ST CORNER NATIONAL ROAD POBLACION 724441/091658 36764 7-ELEVEN CONVENIENCE EAST SERVICE ROAD ALABANG SERVICE ROAD (BESIDE STORE PETRON) 7-ELEVEN CONVENIENCE G/F REPUBLICA BLDG. MONTILLANO ST. ALABANG 705-5243 STORE MUNT. 7-ELEVEN FOODSTORE UNIT 1 SOUTH STATION ALABANG-ZAPOTE ROAD 5530280 7-ELEVEN FOODSTORE 452 CIVIC PRIME COND. FCC ALABANG 7-ELEVEN/FOODSTORE MOLINA ST COR SOUTH SUPERH-WAY ALABANG 7MARCELS CLOTHING, INC. UNIT 2017-2018 G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER 8128861 MUNTINLUPA CITY 88 SOUTH POINTER INC. UNIT 2,3,4 YELLOW BLDG. SOUTH STATION FILINVEST 724-6096 (PADIS POINT) ALABANG A & C IMPORT EXPORT E RODRIGUEZ AVE TUNASAN 8171586/84227 66/0927- 7240300 A/X ARMANI EXCHANGE G/F CORTE DE LAS PALMAS ALAB TOWN CENTER 8261015/09124 AYALA ALABANG 350227 AAI WORLDWIDE LOGISTICS KM.20 WEST SERV.RD. COR. VILLONGCO ST CUPANG 772-9400/822- INC 5241 AAPI REALTY CORPORATION KM22 EAST SERV RD SSHW CUPANG 8507490/85073 36 AB MAURI PHILIPPINES INC. -

Sscott Megacities S Paulo Rio Edv2

Megacities: A Study of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro Grade Level: 9-12 Subject: Geography, World History Key Words: megacities, urban design Time Frame: 1-2 days Designed by: Sharlyn Scott School District: Desert Vista High School Summary: Using São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro as case studies to research and compare/contrast, students will gain a greater understanding of basic urban geography and the history and geography of Brazil. Background Information: Megacities are urban conglomerations with populations exceeding 10 million; sources vary on exactly how many global cities (and their urban sprawl) can be categorized as such. According to the United Nations, there were an estimated 37 cities with more than 10 million people in 2015, compared to just 14 in 1995, and they estimate there will be 41 (maybe as many as 43) megacities by 2030. Two of the three megacities in Latin America are in Brazil: São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. For more information about megacities, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro, see: • Blakemore (2016) “Five Things to Know About Megacities” (Smithsonian): https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/five-things-to-know-about- megacities-180958937/ • Catalytic Communities “Favela Facts”: http://catcomm.org/favela-facts/ • "São Paulo: South America’s Megacity”: https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=sNEeY_gXFBc Student Objectives Students will be able to • Consider the needs of human populations within a city (their own as an introduction) and what challenges/successes city planners and leaders, as well as the population of that city, experience. • Research characteristics of the physical geography and human geography of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in order to create together a clearer picture and understanding of these two megacities in Brazil, and the successes/challenges both have experienced. -

COVID-19 Government Hotlines

COVID-19 Advisory COVID-19-Related Government Hotlines Department of Health (DOH) 02-894-COVID (02-894-26843); 1555 (PLDT, Smart, Sun, and TNT Subscribers) Philippine Red Cross Hotline 1158 Metro Manila Emergency COVID-19 Hotlines Caloocan City 5310-6972 / 0947-883-4430 Manila 8527-5174 / 0961-062-7013 Malabon City 0917-986-3823 Makati City 168 / 8870-1959-59 Navotas City 8281-1111 Mandaluyong City 0916-255-8130 / 0961-571-6959 Valenzuela City 8352-5000 / 8292-1405 San Juan City 8655-8683 / 7949-8359 Pasig City 8643-0000 Muntinlupa City 0977-240-5218 / 0977-240-5217 Municipality of Pateros 8642-5159 Paranaque City 8820-7783 Marikina City 161 / 0945-517-6926 Las Pinas City 8994-5782 / 0977-672-6211 Taguig City 0966-419-4510 / 8628-3449 Pasay City 0956-7786253 / 0908-9937024 Quezon City 122 Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) (+632) 8807-2631 Department of the Interior and Local (+632) 8876-3444 local 8806 ; Government (DILG) Emergency 8810 to monitor the implementation of directives and Operations Center Hotline measures against COVID-19 in LGUs Department of Trade and Industry 0926-612-6728 (Text/Viber) DTI Officer of the Day COVID Rapid Response Team deployed in NDRRMC Camp Aguinaldo Other Government Hotlines Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) (+632) 8708.77.01 Email: [email protected] Credit Information Corporation (CIC) Email: [email protected] Social Security System (SSS) Trunkline: (+632) 8920-6401 Call Center: (+632) 8920-6446 to 55 IVRS: (+632) 7917-7777 Toll Free: 1-800-10-2255777 Email: [email protected] -

Megacities and Tall Buildings: Symbiosis

E3S Web of Conferences 33, 01001 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20183301001 HRC 2017 Megacities and tall buildings: symbiosis Daniel Safarik1*, Shawn Ursini1 and Antony Wood1 1Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, 104 South Michigan Ave., Suite 620, Chicago, IL, 60603, United States Abstract. Anyone concerned with the development of human civilization in the 21st Century will likely have heard the term «megacity». It is – as it should be – increasingly prevalent in both mainstream and academic discussions of the great trends of our time: urbanization, rising technological and physical connectivity, increasingly polarized extremes of wealth and poverty, environmental degradation, and climate change. It is a subject as large and far-reaching as its name implies. This paper sets the scene on how megacities and the built environment are growing together, and examines the implications for those who plan, design, develop and operate tall buildings and urban infrastructure. 1 What is a Megacity? In order to rationalize the data CTBUH collects – predominantly on skyscrapers and large urban developments – with that collected by other organizations, first a definition that reflects a distillation of the prominent literature on the subject should be set forth: A megacity is an urban agglomeration with a total population of 10 million people or greater, consisting of a continuous built-up area that encompasses one or more city centers and suburban areas, economically and functionally linked to those centers. A megacity is typically, though not always, polycentric, with multiple nodes of concentrated urban activity and high-density development, rather than being centered around one large primary central business district (CBD). -

Robinson Herrera on Mexico Megacity

James B. Pick, Edgar W. Butler. Mexico Megacity. Boulder, Col.: Westview Press, 1997. xviii + 411 pp. $90.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8133-8983-7. Reviewed by Robinson A. Herrera Published on H-Urban (March, 1999) Despite the existence of other important ur‐ economic, environmental, labor force, and corpo‐ ban centers in modern Mexico, Mexico City re‐ rate themes" (p. 2). mains the nucleus of political and economic pow‐ In the tradition of quantitative studies pio‐ er. In the last decades it has come to dominate neered by serials such as the Statistical Abstract popular culture as well, primarily due to its role of Latin America[1], Pick and Butler hesitate to in‐ as the central base for the country's television, ra‐ terpret the information too profoundly, preferring dio, and newspaper industries. To better under‐ instead to provide data, analysis, and narrative.[2] stand this massive metropolis' problems and po‐ This does not mean that Mexico Megacity is a tential, James B. Pick (professor of management mere collection of raw data, but it does demon‐ and business) and Edgar W. Butler (professor of strate the authors' greater interest in presenting sociology) have examined a forty-year period in findings and supporting data than in making val‐ the life of the city, from 1950-1990, occasionally ue judgments. Yet, at times, particularly in cases extending their analysis to 1930. The resulting dealing with the unequal distribution of resources work, Mexico Megacity, titled thus after the latest that result in exploitation, Pick and Butler do not moniker applied to the city under study, ranks as refrain from expressing their opinions. -

Issues and Directions on Integrated Public Transport in Metropolitan Manila

Proceedings of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol.6, 2007 ISSUES AND DIRECTIONS ON INTEGRATED PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN METROPOLITAN MANILA Noriel Christopher C. TIGLAO Ildefonso T. PATDU, Jr. Assistant Professor Director, Planning Service National College of Public Administration Department of Transportation and and Governance Communications University of the Philippines, Diliman Columbia Tower, Ortigas Avenue 1101 Quezon City, PHILIPPINES 1555 Mandaluyong City, PHILIPPINES Telefax: +63-2-928-3861 Telefax: +63-2-727-7960 Email: [email protected] Email:[email protected] Abstract: The urban population of Metro Manila continues to expand along with high rates of suburbanization at adjoining municipalities. This greater metropolitan region is now referred to as 'Mega Manila'. The resulting urban pattern is one where an increasing number of people live at the fringes of the metropolitan area but still need to travel to the city centers to work or study. In order to sustain economic growth and development and to protect the environment in the region, there is a need to increase mobility through the provision of an integrated public transport system. This paper reviews the various sustainable development and management issues and policies impinging on the public transport system of Metro Manila. The paper also reviews and evaluates existing policy directions in relation to the development of an integrated public transport system for the metropolis. Key Words: integrated public transport, sustainable development, mega-city 1. INTRODUCTION The urban population of Metro Manila continues to expand along with high rates of suburbanization at adjoining municipalities. This greater metropolitan region is now referred to as 'Mega Manila'. -

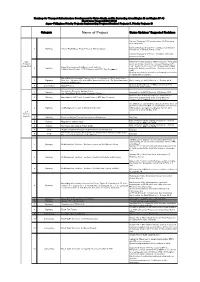

Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions

Roadmap for Transport Infrustructure Development for Metro Manila and Its Surrunding Areas(Region III and Region IV-A) Short-term Program(2014-2016) Japan-Philippines Priority Projects: Implementing Progress(Comitted Projects 5, Priority Projects 8) Category Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions Contract Packages I & II covering about 14.65 km have been completed. Contract Package III (2.22 km + 2 bridges): Construction 1 Highways Arterial Road Bypass Project Phase II, Plaridel Bypass Progress as of 25 April 2015 is 13.02%. Contract Package IV (7.74 km + 2 bridges): Still under procurement stage. ODA Notice to Proceed Issued to CMX Consortium. The project Projects is not specifically cited in the Transport Roadmap. LRT (Committed) Line 1 South Ext and Line 2 East Ext were cited instead, Capacity Enhancement of Mass Transit Systems 2 Railways separately. Updates on LRT Line 1 South Extension and in Metro Manila Project (LRT1 Extension and LRT 2 East Extentsion) O&M: Ongoing pre-operation activities; and ongoing procurement of independent consultant. Metro Manila Interchanges Construction VI - 2 packages d. EDSA/ North Ave. - 3 Highways West Ave.- Mindanao Ave. and EDSA/ Roosevelt Ave. and f. C5: Green Meadows/ Confirmed by the NEDA Board on 17 October 2014 Acropolis/CalleIndustria Ongoing. Detailed Design is 100% accomplished. Final 4 Expressways CLLEX Phase I design plans under review. North South Commuter Railway Project 1 Railways Approved by the NEDA Board on 16 February 2015 (ex- Mega Manila North-South Commuter Railway) New Item, Line 2 West Extension not included in the 2 Railways Metro Manila CBD Transit System Project (LRT2 West Extension) short-term program (until 2016).