GNOSTIC ELEMENTS in HERMETIC TRADITIONS Islamic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

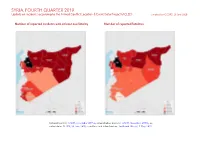

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

ROUTES and COMMUNICATIONS in LATE ROMAN and BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (Ca

ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY TÜLİN KAYA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SETTLEMENT ARCHAEOLOGY JULY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. D. Burcu ERCİYAS Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Suna GÜVEN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ufuk SERİN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşe F. EROL (Hacı Bayram Veli Uni., Arkeoloji) Assist. Prof. Dr. Emine SÖKMEN (Hitit Uni., Arkeoloji) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Tülin Kaya Signature : iii ABSTRACT ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) Kaya, Tülin Ph.D., Department of Settlement Archaeology Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr. -

Offprint / Ayribasim

JMR BURSA ULUDAĞ UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF MOSAIC RESEARCH AIEMA - TÜRkİye SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE / BILIMSEL KOMITE CATHERINE BALMELLE (CNRS PARIS-FRANSA/FRANCE), JEAN-PIERRE DARMON (CNRS PARIS-FRANSA/FRANCE), MARIA DE FÁTIMA ABRAÇOS (UNIVERSITY NOVA of LISBON – PORTEKIZ/PORTUGAL), MARIA DE JESUS DURAN KREMER (UNIVERSITY NOVA of LISBON – PORTEKIZ/PORTUGAL), MICHEL FUCHS (LAUSANNE UNIVERSITY – ISVIÇRE/SWISS), KUTAlmıs GÖRKAY (ANKARA ÜNIVERSITESI – TÜRKIYE), ANNE-MARIE GUIMIER-SORBETS (AIEMA – FRANSA/FRANCE), WERNER JOBST (AUSTRIAN ACADEMY of SCIENCES – AVUSTURYA/ AUSTRIA), I. HAKAN MERT (BURSA UludAG˘ ÜNIVERSITESI –TÜRKIYE), MARIA LUZ NEIRA JIMÉNEZ (UNIVERSIDAD CARLOS III DE MADRID - IspANYA- SPAIN), ASHER OVADIAH (TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY – ISRAIL/ISRAEL), MEHMET ÖNAL (HARRAN ÜNIVERSITESI – TÜRKIYE), DAVID PARRISH (PURDUE UNIVERSITY – A.B.D./U.S.A), GÜRCAN POLAT (EGE ÜNIVERSITESI – TÜRKIYE), MARIE-PATRICIA RAYNAUD (CNRS PARIS – FRANSA/FRANCE ), DERYA AHIN (BURSA UludAG˘ ÜNIVERSITESI – TÜRKIYE), MUSTAFA AHIN(BURSA UludAG˘ÜNIVERSITESI–TÜRKIYE), Y. SELÇUK ENER (GAZI ÜNIVERSITESI – TÜRKIYE), EMINE TOK (EGE ÜNIVERSITESI – TÜRKIYE), PATRICIA WITTS (AIEMA– BIRLEŞIK KRALLIK/UNITED KINGdom), LICINIA N.C. WRENCH (NEW UNIVERSITY of LISBON – PORTEKIZ/PORTUGAL) OFFPRINT / AYRIBASIM VOLUME 11 2018 Bursa Uludağ University Press Bursa Uludağ Üniversitesi Yayınları Bursa Uludağ University Mosaic Research Center Bursa Uludağ Üniversitesi Mozaik Araştırmaları Merkezi Series - 3 Serisi - 3 JMR - 11 BURSA ULUDAĞ UNIVERSITY BURSA ULUDAĞ ÜNİVERSİTESİ JMR Prof. Dr. Yusuf -

Urfa-Harran Houses and Living Spatial Places

International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology ISSN: 2313-3759 Vol. 4 No. 1; January 2017 Urfa-Harran Houses and Living Spatial Places Dizdar Safiye İrem Mersin University Architectural Faculty Architectural Department Mersin-Turkey 1. INTRODUCTION Şanlıurfa, which is one of the important cities of the southeast Anatolia region and central Euphrates area, was established at the head of the Balıklıgöl watershed on the north of Harran that stretches along a north-south axis. The settlement was established on the streambed plateau which, with the Harran plain, was created in the Eocene-Miocene geological periods in an area rich in water and defense and economic resources. The Urfa and Harran houses which hold an important place in Anatolian domestic architecture became the topic of study for various disciplines in the context of the effect of human-nature interaction. In this study the characteristics of Harran house architecture and the possibility of its sustainability were examined. What was generally encountered in the southeastern Anatolian settlement region in spatial formation: architectural characteristics like the organizational plan with the courtyard closed to the outside and turned inwards, the block building technique and the use of regional material; as for in the societal understanding family structure, religious structure and economic and cultural influences were most important. In Anatolia the history of settlements stretches from our day back 11,000-12,000 years. The factors influential in the creation of the houses that made up the settlements may be examined in two groups as natural and human factors. The natural factors may be evaluated as climate, land formations and material while the human factors may be evaluated as characteristics of the social-economic and user-based plan. -

An Ethnobotanical Investigation on the Baskets of Mardin, South East Anatolia Hasan AKAN*,1 1Harran University, Arts & Scien

ADYÜTAYAM Cilt 1, Sayı 1: 21-30, 2013. Akan H. An Ethnobotanical Investigation on The Baskets of Mardin, South East Anatolia Hasan AKAN*,1 1Harran University, Arts & Science Faculty, Biology Department, Osmanbey Campus, 63300, Şanlıurfa. ABSTRACT In this study, it is explored how woody plants used in making handicraft of baskets in Midyat, Nusaybin, Akarsu, Kızıltepe provinces of Mardin, and how they are processed. In this area, six woody taxa is recorded (Salix viminalis L., Populus nigra L. subsp. nigra, Punica granatum L., Celtis australis L., Cornus sanguineae L. subsp. australis (C.A.Meyer) Jav and Anagyris foetida L.) in basket production. The local names of the baskets determined in this province, how these trees are processed, scientific and local names of these trees, where they are obtained, and archives of the photographs taken during this study are given. Key Words: Ethnobotanic, Baskets, Handicraft, Mardin Mardin (Güneydoğu Anadolu Bölgesi) Zembilleri Üzerine Etnobotanik Bir Araştırma ÖZET Bu çalışmada, Mardin’in ilçeleri olan Midyat, Nusaybin, Akarsu ve Kızıltepe’de sepetçilik el sanatında odunsu bitkilerden sepetlerin nasıl yapıldığı ve işlendiği araştırılmıştır. Bu bölgede 6 bitki türünün sepet yapımında kullanıldığı tespit edilmiştir. Bunlar; Salix viminalis L., Populus nigra L. subsp. nigra, Punica granatum L., Celtis australis L., Cornus sanguineae L. subsp. australis (C.A.Meyer) Jav ve Anagyris foetida L.’dır. Bölgede, sepetlerin yöresel isimleri, ağaçların nasıl işlendiği, bitkilerin bilimsel ve yöresel isimleri, nereden temin edildikleri araştırılmış ve çalışma boyunca çekilen fotoğraflar arşivlenmiştir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Etnobotanik, Sepetler, El Sanatları, Mardin * Corresponding Author/ Yazışmalardan Sorumlu Yazar: Hasan AKAN Harran University, Arts & Science Faculty, Biology Department, Osmanbey Campus, 63300, Şanlıurfa, Turkey. -

On an Asaccus Elisae

TurkJZool 26(2002)315-316 ©TÜB‹TAK ResearchNote OnanAsaccuselisae (F.Werner,1895)(Sauria:Gekkonidae) SpecimenCollectedfromtheVicinityofNusaybin,Mardin CemalVarolTOK ÇanakkaleOnsekiz MartUniversity,FacultyofScienceandArts,DepartmentofBiology,Terzio¤luCampus,Çanakkale-TURKEY MehmetKutsayATATÜR,DurmuflC‹HAN EgeUniversity,FacultyofScience,DepartmentofBiology,35100,Bornova,‹zmir-TURKEY Received:25.12.2001 Abstract: AsingleAsaccuselisae specimen,whichwascaughtfromthevicinityofNusaybin,MardininSEAnatolia,wasexamined morphologically.ThepreviousknownlocalityofthespeciesinAnatoliawasBirecik,nearfianl›urfa. KeyWords: Asaccuselisae,Morphology,Distribution Nusaybin(Mardin)Civar›ndanToplananAsaccuselisae (F.WERNER,1895) (Sauria:Gekkonidae)Örne¤iHakk›nda Özet: Buçal›flmada,Güneydo¤uAnadolu’daNusaybin(Mardin)civar›ndantoplananbir Asaccuselisae örne¤imorfolojikolarakince- lenmifltir.TürünAnadolu’daöncedenbilinenlokalitesiBirecik(fianl›urfa)’tir. AnahtarSözcükler: Asaccuselisae,Morfoloji,Da¤›l›fl Introduction MaterialandMethods FormerlyknownasPhyllodactyluselisae (1),thefirst Thespecimenwascaughtonthewallofaconcrete reportofthespeciesinTurkeywasfromthevicinityof wellnearawateringcanalofBahçebafl›Village,northof Birecik(2).VerifyingKluge’s(3)claimonsome Nusaybinat3:00p.m. anatomicaldistinctionsof P.elisae,DixonandAnderson Thecolorandpatterncharacteristicsofthespecimen (4)assigned elisae toanewlyerectedgenus: Asaccus. werenoted;thenitwasfixedandputin70%ethanol. BaranandGruber(5)identifiedspecimensfromBirecik asAsacus[sic] elisae.Intheircomparativestudyof Material:ZDEU(ZoologyDepartment–Ege -

Harranlı Çocukların Mahzun Bakışları Altında Yapılan Bir Sempozyum

Harran Ulu Caminin Kalıntısı Kısa Yazılar Harranlı Çocukların Mahzun Bakışları Altında Yapılan Bir Sempozyum I. Uluslar arası Katılımlı Bilim, Din ve Felsefe Tarihinde Harran Okulu Sempozyumu 28-30 Nisan 2006 Şanlıurfa Doğu – batı ve güney – kuzey arasında bir kavşak noktası üzerinde bulunan Harran, şimdiki harabe görüntüsünün aksine bir zaman- ların en güzide şehirlerinden birisiydi. İlk olarak ne zaman ve kim- ler tarafından kurulduğu bilinmeyen Harran’ın bilinen tarihi yak- laşık olarak MÖ ikibinlere kadar gidiyor. Harran’ın hemen yanı başında MÖ 4. yüzyılda bir garnizon şehri olarak kurulan Urfa ise önce Harran’a siyasal ve kültürel anlamda rakip olmuş daha sonra MİLEL VE NİHAL inanç, kültür ve mitoloji araştırmaları dergisi yıl 3 sayı 1-2 Aralık 2005 - Haziran 2006 Kısa Yazılar da MS üçüncü yüzyıldan itibaren Harran’ın önüne geçmiştir. Bu rekabet, Moğolların Harran’ı yerle bir ettiği ve orada yaşayanları Mardin ve diğer illere sürdüğü 13. yüzyılda son bulmuştur. O tarihten sonra bir daha Harran eski ihtişamına hiç kavuşamamıştır. Bugün de küçük bir yerleşim yeri olarak varlığını devam ettirmek- tedir. Harran Anadolu’daki en eski paganist kültüre, Ay Tanrısı Sin kültüne, ev sahipliği yapmanın yanı sıra Ortaçağda içinde barın- dırdığı felsefe okullarıyla özellikle Yunan felsefesinin doğuya ta- şınmasında önemli bir rol üstlenmiştir. İslam dünyasında yetişen Müslüman ya da diğer dinlere mensup pek çok bilim adamı bir şekilde Harran’la ilişki içerisinde olmuştur. Tarihin tozlu sayfaları arasında kalan Harran’a dair olan bilgi- lerin ve bugün güneyden esen çöl rüzgarlarının getirdiği kumlar altında kalan Harran kalıntılarının –gerek Sin kültüyle ilgili olan mabetler ve gerekse Müslümanlarla ilgili olan Harran kalesi ve Ulu Cami- açığa çıkarılması açısından son derece önemli bir sem- pozyum icra edilmiştir. -

Biblical Turkey

Biblical Turkey A Guide to the Jewish and Christian Sites of Asia Minor ISBN: 9786054701483 (pb) by Mark Wilson PRICE: DESCRIPTION: $39.95 (pb) Biblical Turkey has become the authoritative and comprehensive guide to the ancient Jewish and Christian sites in Turkey. It includes all the references to cities, regions, provinces, and natural PUBLICATION DATE: features in the Jewish Bible/Old Testament, Apocrypha/Deuterocanonicals, New Testament, and 30 July 2014 (pb) Apostolic Fathers. Special features include Sidetrips, which point to nearby sites that are also of interest to visitors. The In-Sites help readers to read between the lines for special insights into the BINDING: biblical text. In the Ancient Voice section, writers from antiquity speak about the ancient world of Asia Paperback Minor. Colorful photographs and plans of selected sites illustrate the volume. The third edition incorporates fresh archaeological discoveries including the new excavation at Derbe. Also added is a SIZE: new section on Calneh (Tell Tayinat) and its sister site Alalakh (Tell Atchana). 5 x8 TABLE OF CONTENTS: PAGES: Author's Introduction General Introduction Abbreviations Maps Turkey's Seven Regions with Biblical 400 Sites Jewish Communities in Asia Minor Paul's Anatolian Journeys John's Seven Churches of Asia Peter's Communities Chapter 1: East Region (Dogu Anadolu Bolgesi) Natural Sites Mount Ararat ILLUSTRATIONS: (Agri Dag) Euphrates River Tigris River Ancient Voice: The Gilgamesh Epic Ancient Regions Ararat, col illus. Urartu Togarmah Ancient Cities Tushpa -

Prof. Dr. Orhan AYDIN Rektör DAĞITIM Üniversitemiz Uygulamalı

Evrak Tarih ve Sayısı: 02.03.2021-9857 T.C. TARSUS ÜNİVERSİTESİ REKTÖRLÜĞÜ Genel Sekreterlik Sayı : E-66676008-051.01-84 02.03.2021 Konu : Kongre Duyurusu DAĞITIM Üniversitemiz Uygulamalı Bilimler Fakültesi ev sahipliğinde, Mersin Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi, Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi, Osmaniye Korkut Ata Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi ve Karamanoğlu Mehmetbey Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi işbirliği ile ortaklaşa düzenlenen 08-09 Ekim 2021 tarihleri arasında çevrimiçi olarak gerçekleştirilecek olan “ Uluslararası Dijital İşletme, Yönetim ve İktisat Kongresi (International Digital Business, Management And Economics Congress)’ne ilişkin afiş görseli ekte gönderilmekte olup kongre hakkındaki detaylı bilgilere icdbme2021.tarsus.edu.tr adresinden ulaşılabilecektir. Söz konusu kongrenin kurumunuz ilgili birimlerine ve akademik personeline duyurulması hususunda ; Bilgilerinizi ve gereğini arz ederim. Prof. Dr. Orhan AYDIN Rektör Ek : Afiş (2 Sayfa) Dağıtım : Abdullah Gül Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Acıbadem Mehmet Ali Aydınlar Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Adana Alparslan Türkeş Bilim ve Teknoloji Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Adıyaman Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Akdeniz Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Aksaray Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Alanya Hamdullah Emin Paşa Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Amasya Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Anadolu Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Anka -

Assessment of Irrigation Schemes with Comparative Indicators in the Southeastern Anatolia Project

TurkJAgricFor 27(2003)293-303 ©TÜB‹TAK AssessmentofIrrigationSchemeswithComparativeIndicatorsin theSoutheasternAnatoliaProject HasanDE⁄‹RMENC‹* KahramanmaraflSütçüImamUniversity,FacultyofAgriculture,Dept.ofAgriculturalEngineering, 46100,Kahramanmarafl-TURKEY HakanBÜYÜKCANGAZ,HayrettinKUfiCU Uluda¤University,FacultyofAgriculture,DepartmentofAgriculturalEngineering,16059,Bursa-TURKEY Received:26.05.2003 Abstract: Inthisstudy,6comparativeindicatorsfortheassessmentofirrigationsystemperformancewereappliedto12irrigation schemes,whichwerecomponentsoftheSoutheasternAnatolianProject,fortheperiod1997-2001.Theoutputperunitcropped area,outputperunitcommand,outputperunitirrigationsupply,outputperunitwaterconsumed,relativewatersupplyand irrigationratiowerecalculatedas1223-9436$ha -1,308-5771$ha -1,0.12-2.16$m -3,0.45-2.92$m -3,1.00-5.90,and7- 100%,respectively.ANOVAtestresultsindicatedthatamongtheschemesthedifferencesintheoutputperunitcroppedarea,output perunitirrigationsupply,outputperunitwaterconsumedandrelativewatersupplywerenotstatisticallysignificantbuttha tthe differencesinoutputperunitcommandandirrigationratiowerestatisticallysignificant.Forefficientandrationalirrigati on management,aninformationsystemformonitoringandevaluationwhichencompassesallstakeholders,shouldbesetupand irrigationschedulingshouldbedesigned. KeyWords: Irrigationscheme,comparativeindicators,standardizedgrossvalueofproduction,relativewatersupply,irrigationratio Güneydo¤uAnadoluProjesindeKarfl›laflt›rmaGöstergeleriileSulamafiebekelerinin De¤erlendirilmesi Özet: Buçal›flmada;sulamaflebekelerininsistembaflar›lar›n›nde¤erlendirilmesindealt›karfl›laflt›rmagöstergesi,1997-2001y›llar› -

Biblical World

MAPS of the PAUL’SBIBLICAL MISSIONARY JOURNEYS WORLD MILAN VENICE ZAGREB ROMANIA BOSNA & BELGRADE BUCHAREST HERZEGOVINA CROATIA SAARAJEVO PISA SERBIA ANCONA ITALY Adriatic SeaMONTENEGRO PRISTINA Black Sea PODGORICA BULGARIA PESCARA KOSOVA SOFIA ROME SINOP SKOPJE Sinope EDIRNE Amastris Three Taverns FOGGIA MACEDONIA PONTUS SAMSUN Forum of Appius TIRANA Philippi ISTANBUL Amisos Neapolis TEKIRDAG AMASYA NAPLES Amphipolis Byzantium Hattusa Tyrrhenian Sea Thessalonica Amaseia ORDU Puteoli TARANTO Nicomedia SORRENTO Pella Apollonia Marmara Sea ALBANIA Nicaea Tavium BRINDISI Beroea Kyzikos SAPRI CANAKKALE BITHYNIA ANKARA Troy BURSA Troas MYSIA Dorylaion Gordion Larissa Aegean Sea Hadrianuthera Assos Pessinous T U R K E Y Adramytteum Cotiaeum GALATIA GREECE Mytilene Pergamon Aizanoi CATANZARO Thyatira CAPPADOCIA IZMIR ASIA PHRYGIA Prymnessus Delphi Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Mazaka Sardis PALERMO Ionian Sea Athens Antioch Pisidia MESSINA Nysa Hierapolis Rhegium Corinth Ephesus Apamea KONYA COMMOGENE Laodicea TRAPANI Olympia Mycenae Samos Tralles Iconium Aphrodisias Arsameia Epidaurus Sounion Colossae CATANIA Miletus Lystra Patmos CARIA SICILY Derbe ADANA GAZIANTEP Siracuse Sparta Halicarnassus ANTALYA Perge Tarsus Cnidus Cos LYCIA Attalia Side CILICIA Soli Korakesion Korykos Antioch Patara Mira Seleucia Rhodes Seleucia Malta Anemurion Pieria CRETE MALTA Knosos CYPRUS Salamis TUNISIA Fair Haven Paphos Kition Amathous SYRIA Kourion BEIRUT LEBANON PAUL’S MISSIONARY JOURNEYS DAMASCUS Prepared by Mediterranean Sea Sidon FIRST JOURNEY : Nazareth SECOND