The Security Sector in Southern Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Botswana 2020 Human Rights Report

BOTSWANA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Botswana is a constitutional, multiparty, republican democracy. Its constitution provides for the indirect election of a president and the popular election of a National Assembly. The Botswana Democratic Party has held a majority in the National Assembly since the nation’s founding in 1966. In October 2019 President Mokgweetsi Masisi won his first full five-year term in an election that was considered free and fair by outside observers. The Botswana Police Service, which reports to the Ministry of Defense, Justice, and Security, has primary responsibility for internal security. The Botswana Defense Force, which reports to the president through the minister of defense, justice, and security, is responsible for external security and has some domestic security responsibilities. The Directorate of Intelligence and Security Services, which reports to the Office of the President, collects and evaluates external and internal intelligence, provides personal protection to high-level government officials, and advises the presidency and government on matters of national security. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Members of the security forces committed some abuses. The National Assembly passed a six-month state of emergency in April and extended it for an additional six months in September. Ostensibly to give the government necessary powers to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, the terms of the state of emergency included a ban on the right of unions to strike, limits on free speech related to COVID-19, and restrictions on religious activities. It also served as the basis for three lockdowns that forced most citizens to remain in their homes for several weeks to curb the spread of the virus. -

OSAC Country Security Report Botswana

OSAC Country Security Report Botswana Last Updated: July 28, 2021 Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses Botswana at Level 4, indicating that travelers should not travel to Botswana due to COVID-19. Review OSAC’s report, Understanding the Consular Travel Advisory System. The Institute for Economics & Peace Global Peace Index 2021 ranks Botswana 41 out of 163 worldwide, rating the country as being at a High state of peace. Crime Environment The U.S. Department of State has assessed Gaborone as being a HIGH-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government interests. The U.S. Department of State has not included a Crime “C” Indicator on the Travel Advisory for Botswana. Review the State Department’s Crime Victims Assistance brochure. Crime: General Threat Criminal incidents, particularly crimes of opportunity (e.g., purse snatchings, smash-and-grabs from parked cars and in traffic, residential burglaries), can occur regardless of location. Theft of mobile phones, laptop computers, and other mobile devices are common. Criminals can be confrontational. Criminals often arm themselves with knives or blunt objects (e.g., tools, shovels, bats). Botswana has strict gun-control laws, but criminals reportedly smuggle firearms from neighboring countries where weapons are inexpensive and readily available. A public awareness campaign highlights this issue and requests the public report illegal firearms to the police. Reporting indicates instances of non-violent residential burglaries and violent home invasions. Incidents affect local residents, expatriates, and visitors alike. Robberies and burglaries tend to spike during the holiday seasons. -

Botswana Country Report-Annex-4 4Th Interim Techical Report

PROMOTING PARTNERSHIPS FOR CRIMEPREVENTION BETWEEN THE STATE AND PRIVATE SECURITY PROVIDERS IN BOTSWANA BY MPHO MOLOMO AND ZIBANI MAUNDENI Introduction Botswana stands out as the only African country to have sustained an unbroken record of liberal democracy and political stability since independence. The country has been dubbed the ‘African Miracle’ (Thumberg Hartland, 1978; Samatar, 1999). It is widely regarded as a success story arising from its exploitation and utilisation of natural resources, establishing a strong state, institutional and administrative capacity, prudent macro-economic stability and strong political leadership. These attributes, together with the careful blending of traditional and modern institutions have afforded Botswana a rare opportunity of political stability in the Africa region characterised by political and social strife. The expectation is that the economic growth will bring about development and security. However, a critical analysis of Botswana’s development trajectory indicates that the country’s prosperity has it attendant problems of poverty, unemployment, inequalities and crime. Historically crime prevention was a preserve of the state using state security agencies as the police, military, prisons and other state apparatus, such as, the courts and laws. However, since the late 1980s with the expanded definition of security from the narrow static conception to include human security, it has become apparent that state agencies alone cannot combat the rising levels of crime. The police in recognising that alone they cannot cope with the crime levels have been innovative and embarked on other models of public policing, such as, community policing as a public society partnership to combat crime. To further cater for the huge demand on policing, other actors, which are non-state actors; in particular private security firms have come in, especially in the urban market and occupy a special niche to provide a service to those who can afford to pay for it. -

Election Update 2004 Botswana

ELECTION UPDATE 2004 BOTSWANA number 3 17 January 2005 contents Introduction 1 Free and Fair Elections 2 How the International Press Saw the October Poll 2 New Cabinet 3 Botswana Election Audit 4 Election Results 7 Opposition Party Unity in the Making 16 Parliament Adjourns 18 References 19 Compiled by Sechele Sechele EISA Editorial Team Jackie Kalley, Khabele Matlosa, Denis Kadima Published with the assistance of NORAD and OSISA Introduction executive secretary of the Section 65A of the Constitution Independent Electoral of Botswana in 1997 (see Botswana has now been Commission of Botswana Constitution Amendment Act independent for more than 38 (IEC), Mr Gabriel Seeletso. No.18 of 1997); which also years, with one party at the provides for the composition of helm – the Botswana In an interview in his office and the Commission. Democratic Party (BDP). a week after having a week- Elections are held every five long meeting with the The Commission consists of a years in this land-locked, Independent Electoral chairperson (Justice Judge diamond-rich and peaceful state Commission of Botswana; John. Mosojane), deputy and they are always declared Seeletso has expressed chairman (Private Attorney free and fair. The 30 October complete satisfaction with the Omphemetsee Motumisi), and 2004 general elections in performance of his staff and the five other members appointed Botswana were no exception. Commission in correctly and by the Judicial Service competently conducting the Commission from a list of For purposes of this update on 2004 general elections. persons recommended by the the aftermath of the elections, The Independent Electoral All Party Conference. -

Criminal Background Check Procedures

Shaping the future of international education New Edition Criminal Background Check Procedures CIS in collaboration with other agencies has formed an International Task Force on Child Protection chaired by CIS Executive Director, Jane Larsson, in order to apply our collective resources, expertise, and partnerships to help international school communities address child protection challenges. Member Organisations of the Task Force: • Council of International Schools • Council of British International Schools • Academy of International School Heads • U.S. Department of State, Office of Overseas Schools • Association for the Advancement of International Education • International Schools Services • ECIS CIS is the leader in requiring police background check documentation for Educator and Leadership Candidates as part of the overall effort to ensure effective screening. Please obtain a current police background check from your current country of employment/residence as well as appropriate documentation from any previous country/countries in which you have worked. It is ultimately a school’s responsibility to ensure that they have appropriate police background documentation for their Educators and CIS is committed to supporting them in this endeavour. It is important to demonstrate a willingness and effort to meet the requirement and obtain all of the paperwork that is realistically possible. This document is the result of extensive research into governmental, law enforcement and embassy websites. We have tried to ensure where possible that the information has been obtained from official channels and to provide links to these sources. CIS requests your help in maintaining an accurate and useful resource; if you find any information to be incorrect or out of date, please contact us at: [email protected]. -

Botswana : Quels Défis Pour La Nouvelle Présidence Masisi ?

Notes de l’Ifri Botswana : quels défis pour la nouvelle présidence Masisi ? Thibaud KURTZ Novembre 2018 Programme Afrique subsaharienne L’Ifri est, en France, le principal centre indépendant de recherche, d’information et de débat sur les grandes questions internationales. Créé en 1979 par Thierry de Montbrial, l’Ifri est une association reconnue d’utilité publique (loi de 1901). Il n’est soumis à aucune tutelle administrative, définit librement ses activités et publie régulièrement ses travaux. L’Ifri associe, au travers de ses études et de ses débats, dans une démarche interdisciplinaire, décideurs politiques et experts à l’échelle internationale. Les opinions exprimées dans ce texte n’engagent que la responsabilité de l’auteur. ISBN : 978-2-36567-942-8 © Tous droits réservés, Ifri, 2018 Couverture : Flag of Botswana with chalk color/Shutterstock.com Comment citer cette publication : Thibaud Kurtz, « Botswana : quels défis pour la prochaine présidence Masisi ? », Notes de l’Ifri, Ifri, novembre 2018. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – FRANCE Tél. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 – Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 E-mail : [email protected] Site internet : Ifri.org Auteur Thibaud Kurtz est consultant indépendant et analyste en géopolitique africaine. Il a mené de nombreuses missions pour des réseaux d’ONG et diplomatiques européens en Afrique australe et des Grands Lacs. Après avoir travaillé au sein d’EurAc à Bruxelles, il a été basé au Botswana pendant plusieurs années, où il a occupé des postes régionaux pour les missions diplomatiques de la France, de l’Union Européenne et du Royaume-Uni. -

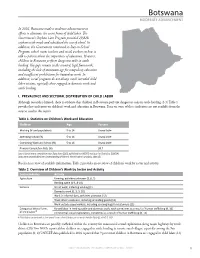

Botswana MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

Botswana MODERATE ADVANCEMENT In 2016, Botswana made a moderate advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. The Government’s Orphan Care Program provided 29,828 orphans with meals and subsidized the cost of school. In addition, the Government continued its Stay-in-School Program, which trains teachers and social workers on how to talk to parents about the importance of education. However, children in Botswana perform dangerous tasks in cattle herding. Key gaps remain in the country’s legal framework, including the lack of minimum age for compulsory education and insufficient prohibitions for hazardous work. In addition, social programs do not always reach intended child labor victims, especially those engaged in domestic work and cattle herding. I. PREVALENCE AND SECTORAL DISTRIBUTION OF CHILD LABOR Although research is limited, there is evidence that children in Botswana perform dangerous tasks in cattle herding.(1-3) Table 1 provides key indicators on children’s work and education in Botswana. Data on some of these indicators are not available from the sources used in this report. Table 1. Statistics on Children’s Work and Education Children Age Percent tŽƌŬŝŶŐ;йĂŶĚƉŽƉƵůĂƟŽŶͿ 5 to 14 Unavailable ƩenĚinŐ ^ĐŚool ;йͿ 5 to 14 Unavailable oŵbininŐ toƌŬ anĚ ^ĐŚool ;йͿ 5 to 14 Unavailable WƌiŵaƌLJ oŵƉleƟon Zate ;йͿ 99.7 ^ŽƵƌĐĞĨŽƌƉƌŝŵĂƌLJĐŽŵƉůĞƟŽŶƌĂƚĞ͗ĂƚĂĨƌŽŵϮϬϭϯ͕ƉƵďůŝƐŚĞĚďLJhE^K/ŶƐƟƚƵƚĞĨŽƌ^ƚĂƟƐƟĐƐ͕ϮϬϭϲ͘;4Ϳ ĂƚĂǁĞƌĞƵŶĂǀĂŝůĂďůĞĨƌŽŵhŶĚĞƌƐƚĂŶĚŝŶŐŚŝůĚƌĞŶ͛ƐtŽƌŬWƌŽũĞĐƚ͛ƐĂŶĂůLJƐŝƐ͕ϮϬϭϲ͘;5Ϳ Based on a review of available information, -

Female Staff Associations in the Security Sector: Agents of Change?”

Inventory of Female Staff Associations Reviewed for the Occasional Paper “Female Staff Associations in the Security Sector: Agents of Change?” Geneva, August, 2011 Inventory of Female Staff Associations Reviewed for the Occasional Paper “Female Staff Associations in the Security Sector: Agents of Change?” Geneva, August 2011 This document is a companion to the DCAF Occasional Paper “Female Staff Associations in the Security Sector: Agents of Change?“ and provides additional background information on all the associations referenced in the paper. About the author Ruth Montgomery is a Canadian policing and criminal justice consultant. She has over 30 years of experience leading police, justice and public safety development and education initiatives nationally and internationally. Ruth retired as a Superintendent from the Edmonton Police Service after 27 years of service and established a consulting firm. She has directed policing and public safety policy and process development initiatives, conducted applied research, and has designed, developed and facilitated educational programmes. Many of her efforts have focused on leadership and management development, and on improving services and support for women. Editor: Kathrin Quesada, Gender and Security Project Coordinator, DCAF Copyright © 2011 by the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces Cover images (from left to right): Japanese junior officers from the Japanese Maritime Self-Defence Force (JMSDF) during a wreath ceremony at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii on June 9, 2010 © Sgt. Cohen A. Young; Seaman Writer Kim-Jade Martin from HMAS Tobruk meets a Papua New Guinean boy at a small coastal villiage in Rabaul during Pacific Partnership September 8, 2010 © Australian Department of Defence; Royal Air Force (RAF) and Fleet Air Arm personnel parade of RAF Cottesmore in Rutland March 31, 2011 © Cpl Fran McKay. -

The Security Sector in Southern Africa

ISS MONOGRAPH 174 Th is monograph is a study of the security sector in six Southern African countries, namely Botswana, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho, Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe. It highlights the strengths and challenges of the various institutions that make Th e security sector up the security sector, including defence, police, Cette monographie est une étude portant sur le prisons, intelligence, private security, oversight secteur de sécurité dans six pays d’Afrique australe, bodies and the policy and legal frameworks in Southern Africa à savoir le Botswana, la République Démocratique under which they operate. Th e monograph THE SECURITY SECTOR IN SOUTHERN AFRICA du Congo, le Lesotho, le Mozambique, l’Afrique represents an attempt to provide baseline data du Sud et le Zimbabwe. Elle fait le point sur les on the security institutions in the region so that forces et les faiblesses des diverses institutions formant le secteur de sécurité à savoir la défense, la we can better determine where security sector police, les prisons, les renseignements, la sécurité reform measures are needed. Th e functioning privée, les agences de surveillance de même que of national security institutions is enhanced by les cadres politiques et légaux qui les régissent. the their harmonization at a regional level. Th e La monographie constitue une tentative de monograph therefore begins with an overview fournir des données de base sur les institutions of SADC’s Organ of Politics, Defence and de sécurité de la région afi n de nous permettre Security Cooperation. de mieux déterminer les domaines dans lesquels la réforme est nécessaire. -

First Sarpcco Un Police Officers Trainers Clinic Ptc, Maseru, Lesotho 29 October – 10 November 2007

1 FIRST SARPCCO UN POLICE OFFICERS TRAINERS CLINIC PTC, MASERU, LESOTHO 29 OCTOBER – 10 NOVEMBER 2007 The first ever SARPCCO UNPOC Trainers Clinic took place at the Police Training College, Maseru, Lesotho, from 29 October to 10 November 2007. The SARPCCO UNPOC was instituted in 1997 as a collaborative support between the Training for Peace (TfP) Programme at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), following the onset of democracy in South Africa in 1994. The main purpose of the UNPOC training then, as now, is to build the capacity of the member states of SARPCCO and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region in building and enhancing the capacity for peace operations mandated by the regional organisation, the AU and the UN. In this regard, the course was originally presented as a normal course for rank and file police officers. In recent years, however, the course has been targeted against trainers from training institutions or managers of training from the member states of SARPCCO, or as pre-deployment training, in addition to its presentation for the standby police contributions of the member states to the emerging SADC Standby Force. In an effort to improve on the effectiveness of the course, the SARPCCO Training Sub-Committee in 2006 accepted the recommendation to institutionalise quality assurance measures. These measures consisted of pre-course and assimilation/progress tests on all aspects of the course. The results of the tests and the assessment of topical presentations by the participants serve as a rough tool to gauge the performance and training skills competence of the participants. -

Recentralizing Community Based Natural Resource Management in Botswana, 1996-2012

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 15, Issue 1 | December 2014 Elephants are Like Our Diamonds: Recentralizing Community Based Natural Resource Management in Botswana, 1996-2012 PARAKH HOON Abstract: When the Botswana parliament passed a Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) policy in 2007, ten years after its implementation, the formal policy rejected some of the basic precepts of community based conservation—those who face the costs of living in close proximity to wildlife should receive a major share of benefits. In the national debate over the CBNRM policy, benefits from wildlife were seen analogous to diamonds to be shared by the nation. The paper explains how and why Botswana’s CBNRM policy took this direction through an analysis of three key aspects: subnational bureaucratic and community-level decision-making, national political economy and shifting coalition dynamics in a dominant one party system, and the contestation between transnational indigenous peoples’ networks and the Botswana government. By understanding the CBNRM process as it unfolded at the national, district, and local level over an extended period of time, the paper provides a longitudinal argument about CBNRM recentralization in Botswana. Introduction Use rights meant different things in practice. It was not any devolution of authority or development and management capacity at the local level. Rather, it was a complicated recipe for organizing villages by establishing by-laws for some form of decision-making into community-based organizations or trusts with a boilerplate set of rules. 1 The above statement reflects the frustration that conservationists have with community based approaches in natural resource management in Botswana and indeed elsewhere in Africa. -

African Elephant Summit Gaborone, Botswana 2-4 December 2013

African Elephant Summit Gaborone, Botswana 2-4 December 2013 Summary Record Financial support for the African Elephant Summit was provided by: The Government of Botswana and IUCN would also like to express deepest appreciation to the following individuals and institutions for their assistance: • From the Ministry of Environment Water and Tourism and the Department of Wildlife and National Parks – Minister Tshekedi Khama, Permanent Secretary Mr. Neil Fitt, Jimmy Opelo, Pako Nyepi, Rapelang Mojaphoko, Mable Bolele, Caroline Bogale-Jaiyeoba, Mr. Mui, Kebaabetswe Thwala, Gadifele Moaisi, Modumo, Badisa Sekonopo, Abednico Macheme, Phemelo Ramalefo, Dr. Cyril Taolo, Dr. Oldman Koboto, and the rest of their team, including the many protocol officers and drivers; • From the Government of Botswana - Ministry of Youth and Culture, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Office of the President, Police & Security, Immigration, Botswana Unified Revenue Service; • everyone on the IUCN team - Dr. Jane Smart, Aimé Nianogo, Aban Kabraji, Simon Stuart, Richard Jenkins, Dena Cator, Abdalla Shah, Julia Marton-Lefevre, Cecily Nyaga, Martha Bechem, Scott Perkin, Peter Cruickshank, Ewa Magiera, Diane Skinner (Summit Coordinator), Ali Kaka (Summit Co-Leader), and Holly Dublin (Summit Co-Leader); • Julian Blanc from the CITES MIKE programme and Tom Milliken from TRAFFIC – ETIS for helping prepare the background document and status update; • Mr. Moses Mapesa and Ms. Josephine Mayanja-Nkangi for support in planning; • Elephants Without Borders for their support to the gala dinner; • Amy Crosbie and Electra Vye of Chain of Events, and their team; • the staff and interpreters of the Gaborone International Conference Centre and the Grand Palm Walmont and Metcourt; and • the entertainers throughout the event - SOS Serowe Marimba Band, Mafhitlhakgosi Traditional Dance Group, and Ngwao Lotshwao Traditional Dance Group.