Pakistan-U.S. Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

01-2180-2 CH 01:0545-1 10/13/11 10:47 AM Page 1 stephen p. cohen 1 Pakistan: Arrival and Departure How did Pakistan arrive at its present juncture? Pakistan was originally intended by its great leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, to transform the lives of British Indian Muslims by providing them a homeland sheltered from Hindu oppression. It did so for some, although they amounted to less than half of the Indian subcontinent’s total number of Muslims. The north Indian Muslim middle class that spearheaded the Pakistan movement found itself united with many Muslims who had been less than enthusiastic about forming Pak- istan, and some were hostile to the idea of an explicitly Islamic state. Pakistan was created on August 14, 1947, but in a decade self-styled field marshal Ayub Khan had replaced its shaky democratic political order with military-guided democracy, a market-oriented economy, and little effective investment in welfare or education. The Ayub experiment faltered, in part because of an unsuccessful war with India in 1965, and Ayub was replaced by another general, Yahya Khan, who could not manage the growing chaos. East Pakistan went into revolt, and with India’s assistance, the old Pakistan was bro- ken up with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. The second attempt to transform Pakistan was short-lived. It was led by the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who simultaneously tried to gain control over the military, diversify Pakistan’s foreign and security policy, build a nuclear weapon, and introduce an economic order based on both Islam and socialism. -

SBF Book Report Full Final

Shaheed Bhutto Foundation The Shaheed Bhutto Foundation, registered in 2006, is a nonprofit, apolitical, and nongovernmental welfare organization. Shaheed Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto, its Founding Patron, approved its establishment in Dubai on December 3, 2005 with the inclusion of a democracy institute in its charter. The Institute was dedicated to her and named the Benazir Democracy Institute (BDI). Vision: The Foundation envisages having a prosperous Pakistan where justice prevails and citizens are valued irrespective of their race, religion, political opinion, or gender. Mission and Objectives: The Foundation strives to provide social service access to enhance the ability of people through personal behavior to attain optimal "human capital and development" outcomes by utilization of quality social services which are made available on the basis of need and equity within the consolidated means of civil society, governments at various tiers, communities, and partners in development. One of the main objectives of the Foundation is to facilitate the institutionalization of democratic norms at various levels of the society and struggles for strengthening of democracy and democratic institutions in Pakistan. The Foundation routinely organizes seminars, workshops, free medical camps, national dialogues, and advocacy events to sensitize the civil society towards the need to safeguard human rights and other interests of the masses. Main Areas of Work: The Foundation has eight main components and since its inception, it has endeavored to serve the people of Pakistan in these areas: 1. Benazir Democracy Institute; 2. Peoples Health Program; 3. Peoples Education Program; 4. Peoples Legal Aid Program; 5. Peoples Women Empowerment Program; 6. Peoples Micro credit Program; 7. -

Who Is Who in Pakistan & Who Is Who in the World Study Material

1 Who is Who in Pakistan Lists of Government Officials (former & current) Governor Generals of Pakistan: Sr. # Name Assumed Office Left Office 1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah 15 August 1947 11 September 1948 (died in office) 2 Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin September 1948 October 1951 3 Sir Ghulam Muhammad October 1951 August 1955 4 Iskander Mirza August 1955 (Acting) March 1956 October 1955 (full-time) First Cabinet of Pakistan: Pakistan came into being on August 14, 1947. Its first Governor General was Muhammad Ali Jinnah and First Prime Minister was Liaqat Ali Khan. Following is the list of the first cabinet of Pakistan. Sr. Name of Minister Ministry 1. Liaqat Ali Khan Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Defence Minister, Minister for Commonwealth relations 2. Malik Ghulam Muhammad Finance Minister 3. Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar Minister of trade , Industries & Construction 4. *Raja Ghuzanfar Ali Minister for Food, Agriculture, and Health 5. Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar Transport, Communication Minister 6. Fazal-ul-Rehman Minister Interior, Education, and Information 7. Jogendra Nath Mandal Minister for Law & Labour *Raja Ghuzanfar’s portfolio was changed to Minister of Evacuee and Refugee Rehabilitation and the ministry for food and agriculture was given to Abdul Satar Pirzada • The first Chief Minister of Punjab was Nawab Iftikhar. • The first Chief Minister of NWFP was Abdul Qayum Khan. • The First Chief Minister of Sindh was Muhamad Ayub Khuro. • The First Chief Minister of Balochistan was Ataullah Mengal (1 May 1972), Balochistan acquired the status of the province in 1970. List of Former Prime Ministers of Pakistan 1. Liaquat Ali Khan (1896 – 1951) In Office: 14 August 1947 – 16 October 1951 2. -

ORF Issue Brief 17 FINAL

EARCH S F E O R U R N E D V A R T E I O S N B O ORF ISSUE BRIEF APRIL 2009 ISSUE BRIEF # 17 Military-militant nexus in Pakistan and implications for peace with India By Wilson John n November 26, 2008, 10 terrorists who There is otherwise substantial evidence that shows attacked Mumbai undid in less than 60 the Mumbai attack was planned and executed with Ohours what governments of two the help of present and former ISI and Army sovereign nations had been struggling for over four officers who form part of a clandestine group set up years to achieve-peace and stability in the region. to pursue the Army's duplicitous policy of These terrorists were from Pakistan, recruited, protecting its allies among the terrorist groups trained and armed by Lashkar-e-Tayyeba (LeT), a operating within the country while fighting others terrorist group with visible presence across the for the US as part of the Global War on Terror.1 country. The group has clear allegiance to the global terrorist groups like al Qaida and has a presence in This strategic military-militant collusion in Pakistan, over 21 countries. which shows no signs of breaking up, will remain the most critical stumbling block in any future It is well known that terrorist groups like LeT could attempt to mend the relationship between India and not have weathered eight years of global sanctions Pakistan. Arguing the case for dismantling the without the support of the State, and in case of terrorist infrastructure in Pakistan as a pre- Pakistan, it has to be the Pakistan Army and its condition for reviving the peace process, this paper intelligence agency, ISI. -

Pakistan: the Worsening Conflict in Balochistan

PAKISTAN: THE WORSENING CONFLICT IN BALOCHISTAN Asia Report N°119 – 14 September 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. CENTRALISED RULE AND BALOCH RESISTANCE ............................................ 2 A. A TROUBLED HISTORY .........................................................................................................3 B. RETAINING THE MILITARY OPTION .......................................................................................4 C. A DEMOCRATIC INTERLUDE..................................................................................................6 III. BACK TO THE BEGINNING ...................................................................................... 7 A. CENTRALISED POWER ...........................................................................................................7 B. OUTBREAK AND DIRECTIONS OF CONFLICT...........................................................................8 C. POLITICAL ACTORS...............................................................................................................9 D. BALOCH MILITANTS ...........................................................................................................12 IV. BALOCH GRIEVANCES AND DEMANDS ............................................................ 13 A. POLITICAL AUTONOMY .......................................................................................................13 -

Islamist Militancy in the Pakistan-Afghanistan Border Region and U.S. Policy

= 81&2.89= .1.9&3(>=.3=9-*=&0.89&38 +,-&3.89&3=47)*7=*,.43=&3)=__=41.(>= _=1&3=74389&)9= 5*(.&1.89=.3=4:9-=8.&3=++&.78= *33*9-=&9?2&3= 5*(.&1.89=.3=.))1*=&89*73=++&.78= 4;*2'*7=,+`=,**2= 43,7*88.43&1= *8*&7(-=*7;.(*= 18/1**= <<<_(78_,4;= -.10-= =*5479=+47=43,7*88 Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress 81&2.89= .1.9&3(>=.3=9-*=&0.89&38+,-&3.89&3=47)*7=*,.43=&3)=__=41.(>= = :22&7>= Increasing militant activity in western Pakistan poses three key national security threats: an increased potential for major attacks against the United States itself; a growing threat to Pakistani stability; and a hindrance of U.S. efforts to stabilize Afghanistan. This report will be updated as events warrant. A U.S.-Pakistan relationship marked by periods of both cooperation and discord was transformed by the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States and the ensuing enlistment of Pakistan as a key ally in U.S.-led counterterrorism efforts. Top U.S. officials have praised Pakistan for its ongoing cooperation, although long-held doubts exist about Islamabad’s commitment to some core U.S. interests. Pakistan is identified as a base for terrorist groups and their supporters operating in Kashmir, India, and Afghanistan. Since 2003, Pakistan’s army has conducted unprecedented and largely ineffectual counterterrorism operations in the country’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) bordering Afghanistan, where Al Qaeda operatives and pro-Taliban insurgents are said to enjoy “safe haven.” Militant groups have only grown stronger and more aggressive in 2008. -

3 Who Is Who and What Is What

3 e who is who and what is what Ever Success - General Knowledge 4 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success Revised and Updated GENERAL KNOWLEDGE Who is who? What is what? CSS, PCS, PMS, FPSC, ISSB Police, Banks, Wapda, Entry Tests and for all Competitive Exames and Interviews World Pakistan Science English Computer Geography Islamic Studies Subjectives + Objectives etc. Abbreviations Current Affair Sports + Games Ever Success - General Knowledge 5 Saad Book Bank, Lahore © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced In any form, by photostate, electronic or mechanical, or any other means without the written permission of author and publisher. Composed By Muhammad Tahsin Ever Success - General Knowledge 6 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Dedicated To ME Ever Success - General Knowledge 7 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success - General Knowledge 8 Saad Book Bank, Lahore P R E F A C E I offer my services for designing this strategy of success. The material is evidence of my claim, which I had collected from various resources. I have written this book with an aim in my mind. I am sure this book will prove to be an invaluable asset for learners. I have tried my best to include all those topics which are important for all competitive exams and interviews. No book can be claimed as prefect except Holy Quran. So if you found any shortcoming or mistake, you should inform me, according to your suggestions, improvements will be made in next edition. The author would like to thank all readers and who gave me their valuable suggestions for the completion of this book. -

South Asia @ LSE: “We Have Some Critical National Security Interests, and You Have to Be Respectful of Those Interests” – General Haq Page 1 of 2

South Asia @ LSE: “We have some critical national security interests, and you have to be respectful of those interests” – General Haq Page 1 of 2 “We have some critical national security interests, and you have to be respectful of those interests” – General Haq LSE South Asia Centre and LSE SU Pakistan Development Society recently hosted Ehsan Ul Haq, retired four-star general of the Pakistan Army, for the event titled “Can Intelligence Services Do Good?“. General Haq briefly spoke to Mahima A. Jain after the event. Edited excerpts: Mahima A. Jain (MJ): “For its part, Pakistan often gives safe haven to agents of chaos, violence, and terror.” What is your comment on US President Trump’s stance on combating terrorism in South Asia with more help from India? Pakistan had been a key player in the war on terror, but do you think it’s being sidelined now? Ehsan Ul Haq (EUH): This is not a recent shift. If you look at Barack Obama’s policy from 2009, what President Donald Trump is saying is exactly the same except for the Trump style of making it sound very aggressive. We have always disagreed with the US approach of de-hyphenating Pakistan and India, and then trying to foster a strategic partnership with India without regards to the strategic stability in South Asia. Particularly because Pakistan already has very significant differential in our conventional military capabilities. Nuclear is just a stabiliser. If they are going to arm India against China, it is going to impact extremely seriously on Pakistan’s security dynamics. -

Pakistan Response Towards Terrorism: a Case Study of Musharraf Regime

PAKISTAN RESPONSE TOWARDS TERRORISM: A CASE STUDY OF MUSHARRAF REGIME By: SHABANA FAYYAZ A thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham May 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The ranging course of terrorism banishing peace and security prospects of today’s Pakistan is seen as a domestic effluent of its own flawed policies, bad governance, and lack of social justice and rule of law in society and widening gulf of trust between the rulers and the ruled. The study focused on policies and performance of the Musharraf government since assuming the mantle of front ranking ally of the United States in its so called ‘war on terror’. The causes of reversal of pre nine-eleven position on Afghanistan and support of its Taliban’s rulers are examined in the light of the geo-strategic compulsions of that crucial time and the structural weakness of military rule that needed external props for legitimacy. The flaws of the response to the terrorist challenges are traced to its total dependence on the hard option to the total neglect of the human factor from which the thesis develops its argument for a holistic approach to security in which the people occupy a central position. -

List of Category -I Members Registered in Membership Drive-Ii

LIST OF CATEGORY -I MEMBERS REGISTERED IN MEMBERSHIP DRIVE-II MEMBERSHIP CGN QUOTA CATEGORY NAME DOB BPS CNIC DESIGNATION PARENT OFFICE DATE MR. DAUD AHMAD OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT COMPANY 36772 AUTONOMOUS I 25-May-15 BUTT 01-Apr-56 20 3520279770503 MANAGER LIMITD MR. MUHAMMAD 38295 AUTONOMOUS I 26-Feb-16 SAGHIR 01-Apr-56 20 6110156993503 MANAGER SOP OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT CO LTD MR. MALIK 30647 AUTONOMOUS I 22-Jan-16 MUHAMMAD RAEES 01-Apr-57 20 3740518930267 DEPUTY CHIEF MANAGER DESTO DY CHEIF ENGINEER CO- PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 7543 AUTONOMOUS I 17-Apr-15 MR. SHAUKAT ALI 01-Apr-57 20 6110119081647 ORDINATOR COMMISSION 37349 AUTONOMOUS I 29-Jan-16 MR. ZAFAR IQBAL 01-Apr-58 20 3520222355873 ADD DIREC GENERAL WAPDA MR. MUHAMMA JAVED PAKISTAN BORDCASTING CORPORATION 88713 AUTONOMOUS I 14-Apr-17 KHAN JADOON 01-Apr-59 20 611011917875 CONTRALLER NCAC ISLAMABAD MR. SAIF UR REHMAN 3032 AUTONOMOUS I 07-Jul-15 KHAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110170172167 DIRECTOR GENRAL OVERS PAKISTAN FOUNDATION MR. MUHAMMAD 83637 AUTONOMOUS I 13-May-16 MASOOD UL HASAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110163877113 CHIEF SCIENTIST PROFESSOR PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISION 60681 AUTONOMOUS I 08-Jun-15 MR. LIAQAT ALI DOLLA 01-Apr-59 20 3520225951143 ADDITIONAL REGISTRAR SECURITY EXCHENGE COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD CHIEF ENGINEER / PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 41706 AUTONOMOUS I 01-Feb-16 LATIF 01-Apr-59 21 6110120193443 DERECTOR TRAINING COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD 43584 AUTONOMOUS I 16-Jun-15 JAVED 01-Apr-59 20 3820112585605 DEPUTY CHIEF ENGINEER PAEC WASO MR. SAGHIR UL 36453 AUTONOMOUS I 23-May-15 HASSAN KHAN 01-Apr-59 21 3520227479165 SENOR GENERAL MANAGER M/O PETROLEUM ISLAMABAD MR. -

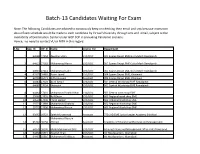

Batch-13 Candidates Waiting for Exam

Batch-13 Candidates Waiting For Exam Note: The following Candidates are advised to consciously keep on checking their email and sms because intimation about Exam schedule would be made to each candidate by Virtual University through sms and email, subject to the availability of Examination Center under GOP SOP in prevailing Pandemic scenario. Hence, no need to contact VU or NITB in this regard. S.No App_ID Off_Sr Name Course_For Department 1 64988 17254 Zeeshan Ullah LDC/UDC 301 Spares Depot EME Golra Morh Rawalpindi 2 64923 17262 Muhammad Harris LDC/UDC 301 Spares Depot EME Golra Morh Rawalpindi 3 64945 17261 Muhammad Tahir LDC/UDC 301 Spares Depot EME Golra Morh Rawalpindi 4 62575 16485 Aamir Javed LDC/UDC 304 Spares Depot EME, Khanewal 5 63798 16471 Jaffar Hussain Assistant 304 Spares Depot EME, Khanewal 6 64383 17023 Asim Ismail LDC/UDC 501 Central Workshop EME Rawalpindi 7 64685 17024 Shahrukh LDC/UDC 501 Central Workshop EME Rawalpindi 8 64464 17431 Muhammad Shahid Khan LDC/UDC 502 Central work shop EME 9 29560 17891 Asif Ehsan LDC/UDC 602 Regional work shop EME 10 64540 17036 Imran Qamar LDC/UDC 602 Regional Workshop EME 11 29771 17889 Muhammad Shahroz LDC/UDC 602 Regional Workshop EME 12 29772 17890 Muhammad Faizan LDC/UDC 602 Regional Workshop EME 13 63662 16523 Saleh Muhammad Assistant 770 LAD EME Junior Leader Academy Shinikiari Muhammad Naeem 14 65792 18156 Ahmed Assistant Academy of Educational Planning and Management 15 64378 18100 Malik Muhammad Bilal LDC/UDC Administrative and Management office GHQ Rawalpind 16 64468 16815 -

Pakistans Inter-Services Intelligence

Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite EINFÜHRUNG 1 Pakistans Inter-Services Intelligence 1 DAS ERSTE JAHRZEHNT 8 1.1 Die Gründungsgeschichte 8 1.2 Gründungsvater Generalmajor Walter J. Cawthorne 9 1.3 Die ISI-Führung der ersten Jahre 11 1.4 Strukturelle Konzepte: 1948-1958 11 2 DIE ZEIT DER ERSTEN GENERÄLE: 1958-1971 14 2.1 Der ISI unter Feldmarschall Ayub Khan (1958-1969) 14 2.2 General Yahya Khan (1969-1971) 20 2.3 Veränderungen in der ISI-Leitungs- und Aufgabenstruktur 23 2.4 ISI und CIA - verstärkte Kooperationen 24 2.5 Operationen in Indien: Die 60er und 70er Jahre 3 REGIERUNGSCHEF ZULFIKAR ALI BHUTTO: 1971-1977 28 3.1 Cherat – Kampfschule der Armee 28 3.2 Brennpunkt Balochistan: Die 70er Jahre 29 3.3 Die Geburt des Special Operation Bureau 3.4 Eine fatale Ernennung: Armeechef Zia-ul-Haq 32 3.5 Innenpolitische Verstrickungen 34 3.6 Der Sturz eines Regierungschefs 37 4 ZWISCHENBILANZ VON 30 JAHREN: 1948-1977 40 5 DER ISI UNTER ZIA-UL-HAQ: 1977-1988 5.1 Die ausgehenden 70er Jahre 44 5.2 Weihnachten 1979: Die Afghanistan-Option 46 5.3 Das Afghanistan-Bureau im ISI 49 5.4 Logistik und Korruption 53 5.5 Ingenieur Gulbuddin Hekmatyar 57 5.6 Das Jahr 1987: Abschied von Akhtar Rehman und Yousaf 58 6 TURBULENZEN ENDE DER ACHTZIGER JAHRE 62 6.1 Von Akhtar Rehman zu Hamid Gul 62 6.2 Die Katastrophe im Ojhri-Camp 63 6.3 Ein Flugzeugabsturz mit Folgen: Der Tod von Zia-ul-Haq 65 6.4 Desaster in Afghanistan: Jalalabad 69 7 INNENPOLITISCH SZENARIEN: 1988-1991 73 7.1 Armeechef General Mirza Aslam Beg 73 7.2 Wahlen und Regierungsbildung 76 7.3 Im ISI: Von Hamid