Page I Submitted by Michael R. Erlanger a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF As Well As Course Slides (Only in French) Are Joined

Transient Fault Tolerant (TFT) 32-bit RISC processor designed by iROC Technologies based on TIMA solutions Micromachined 3D view of a fingerprint Ultrasonic captured with the Transducer - based sweeping mode MEMS tactile pulse-echo system fingerprint sensor CMOS active pixel THESIS system sensor within the vacuum chamber Four-processor System 2.5 Gb/s ATM on Chip with label translator application-specific on- implemented on digital chip communication GaAs network to implement packet routing switch TIMA Laboratory ANNUAL REPORT 2004 May 2005 46, Avenue Félix Viallet 38031 Grenoble Cedex France Tel. :+33 4 76 57 45 00 Fax :+33 4 76 47 38 14 http://tima.imag.fr TIMA Annual Report 2004 3 Abstract The Laboratory has a long experience on hardware design (computer architecture, microprocessor-based architectures, VLSI) and on CAD software (multi-level and mixed-mode simulation, physical design, architectural synthesis, system-level design). Today, the Laboratory is focusing on various aspects of the design, CAD and test of circuits and systems. The Laboratory is approximately 130 people large. It is organized in research groups : Micro and Nano Systems (MNS), Reliable Mixed-signal Systems (RMS), System Level Synthesis (SLS), Verification and modeling of Digital Systems (VDS), QuaLiFication of circuits (QLF), Concurrent Integrated Systems (CIS). The Laboratory is very international : many staff members enjoy 2 countries of citizenship, and there are many foreign researchers and visitors (usually more than 20 countries of citizenship). The Laboratory is also hosting the CMP Service, serving for chips and microsystems fabrication, down to 90 nm. Two multidisciplinary projects are ongoing. One is concerned with the development of the WUCS, Wireless Universal Control System, in view of Ambient Intelligence, and the most recent one is dealing with Quantum Architectures, in cooperation with LEIBNIZ, a theoretical computer science Grenoble-based Lab for Quantum Computing and with Physics and Chemistry Labs working on the implementation of quantum dots. -

Bigger Buzzing Colin King

Journal of the National Autocycle & Cyclemotor Club Ltd. The Buzzing Club Volume 28 Number 5 October 2009 October 2009 Club Information Membership Membership of the NACC costs £9.00 a year plus a £3 joining fee for new or lapsed members. Application forms are available from the Membership Secretary (see previous page). Dating and Registration The current dating fees for club members are: £7 (£10 for non-members) for a certifi cate supporting an application for an age-related registration, £12.50 (£17.50 for non-members) for processing a V765 application. Contact the Machine Registrar for details, please send an SAE. Affi liations The NACC Ltd. is a member of the Federation of British Historic Vehicle Clubs, we have corresponding agreements with; the Register of Unusual Microcars, New Zealand Classic Scooter Club, the Bermuda Classic Bike Club, Rijwiel Hulpmotor Club Nederland, AML GC17 in France, the Sjællands Veteranknallert Klub, Denmark and the British Two Stroke Club. Club Insurance Full and Associate members of the NACC can benefi t from our Footman James NACC Insurance Scheme, offering a range of policies to suit Autocycle, Cyclemotor and Moped owners, including those riding sub-50cc machines on full car licences without a motorcycle licence or CBT. Please quote your membership number when contacting Footman James on 0121 561 6222. Library Alan Hummerstone can supply copies of material held in the NACC Library (contact Alan for a copy of the Library List, see previous page for his details) Website The NACC website www.thebuzzingclub.co.uk is updated frequently and carries all the latest news. -

L'épopée Fantastique

L’épopée fantastique 1820-1920, cycles et motos 8 avril - 25 juillet 2016 Musée national de la Voiture du Palais de Compiègne www.musees-palaisdecompiegne.fr Suriray, Vélocipède de course, 1869. ©RMNGP/Tony Querrec La collection de cycles du musée national de la Voiture compte, pour les années 1818-1920, parmi les plus remarquables d’Europe. Une importante acquisition réalisée en 2015 a permis de notablement l’enrichir et se trouve présentée au public à cette occasion. L’exposition L’Epopée fantastique est organisée autour de différentes thématiques comme les innovations techniques, la recherche de vitesse, les loisirs, les courses, les clubs et la pratique cycliste, ainsi que les impacts sociaux liés au développement des deux-roues entre 1820 et 1920. Des emprunts à d’autres musées français comme le musée Auto Moto de Chatellerault et le musée d’Art et d’Industrie de Saint Etienne, ainsi qu’à des collections privées viennent compléter cette première sélection. C’est à l’occasion du 125e anniversaire de la course Paris-Roubaix, dont le départ a lieu à Compiègne depuis presque quarante ans, que l’exposition sera ouverte au public. On pourra y découvrir les origines du cycle et de la moto et l’extraordinaire émulation qui animait les fabricants, les coureurs, les cyclistes et motards de ces années d’expérimentations et d’exploration qui sont synonymes de nouvelles sensations. L’exposition s’articule autour de quatre axes principaux : 1. Les années 1820-1860 : de la draisienne au vélocipède. Né de la draisienne, inventée par le baron allemand Karl Drais, le vélocipède est issu de la mise en place d’un pédalier sur la roue avant, innovation attribuée au français Pierre Michaux en 1861. -

AANGEBODEN MOTOREN Alcyon, 1908, Erg Vroege Franse Alcyon, Met Nog Wat Werk Maar Wel in Eerste Lak. Meer Info Tel 06-55747521 O

AANGEBODEN MOTOREN Alcyon, 1908, erg vroege Franse Alcyon, met nog wat werk maar wel in eerste lak. Meer info tel 06-55747521 of email info@dutch-lion- motorbikes.com Ariel NH 350cc, 1956, geheel compleet origineel, trappen - lopen - rijden. €2850,- tel 06-20334466 Ariel 500cc OHV, ca. 1929, voor restauratie, compleet, blok los, €7500,-. www.classic-motorcycles.nl, tel 06-30258131 Bevel-Ducati Mille S2, 1986, 973cc, koningsas, 37.500 km, origineel, Conti’s, luchtfilters, extra Silentiums en spoiler, 25 jaar in mijn bezit. €24.500,-, tel 06-53541423 Bianchi 250 cc kopklep 1937, €12.950,-. Yesterdays Antique Motorcycles, tel 0495-546054 www.yesterdays.nl BMW R26, 250cc, 1958. Goed onderhouden, gelijke nrs, Ned. kent. €6350,-. Alltimersmotorcycle classics, tel 06-53439196 www.alltimers.nl BMW R100RS 1978,sterk in prijs verlaagd, voor verdere inlichtingen: [email protected] BMW liefhebbers opgelet! DE KNALPOT, Haltestraat 55 te Rilland meldt HMR onlangs weer een grote partij klassieke BMW’s uit de periode 1950 - 1969 te hebben ontvangen. Bel naar 0113-552298, mail [email protected] of zie www.knalpot.nl voor meer info. BSA KM20, 1939, 500cc zijklepper, in goede staat, €6800,-. www.classic- motorcycles.nl, tel 06-30258131 BSA S29 500 cc kopklep, €11.500,-. Yesterdays Antique Motorcycles, tel 0495-546054 www.yesterdays.nl 98cc DKW met volledige Nederlandse historie, erg mooie staat en zelfs nog met oude foto’s waar je kan zien dat de oude eigenaars er mee in Oostenrijk op vakantie zijn geweest in de jaren vijftig. Voor meer info [email protected] of tel 06-55747521 Douglas CW 350 cc, 1952, €13.950,-. -

Bourgogne 2014

LA VERSION COMPLETE DE VOTRE GUIDE BOURGOGNE 2014 en numérique ou en papier en 3 clics à partir de 5.99€ Disponible sur Bienvenue EDITION Directeurs de collection et auteurs : Dominique AUZIAS et Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE Responsable d’édition : Pascale LEFORT à Bourgogne ! Avec la collaboration de Eric VOILLEQUIN, Josiane MAXEL et Florence PEROUX Auteurs : Delphine TABARY, Isabelle CASSOTTI, Marie-Chantal BAYOL-SORET, Caroline MUSQUET, Anne-Claire DUCHOSSOY, Stacy ARCHAMBAULT, a colline de Vézelay et sa basilique, les douces pentes Isabelle PARRY, Jean-Paul VALENTIN, Olivier COLLET, du vignoble de Puligny-Montrachet, les chênes cente- Karine PALMA, Cédric BLANC, Jeremy GAUTHIOT, L Sophie THOZET, François AUBERT, naires de la forêt de Bertranges, les sources de la Valérie ALAMO BARBELIVEN, Fréderic BRUN, Fabienne AUSSERRE, Valérie MAYINGILA, Jérémy BARBIER, Seine… L’une des premières forces de notre belle région ? Claire DELBARD, Noémie FAVRE COQUERET, Diane AJINA, La variété de ses paysages. Envie de vous ressourcer au cœur Adeline GILLIER, Myriam HENRY, Cynthia BENZIANE, Maxime RONGET, Arnaud AUBRY, Stéphanie QUENON, d'une nature généreuse ? Ici, vous pourrez vous évader au fil Hélène MOULIN, Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE, de l'eau sur les canaux de Bourgogne et du Nivernais, arpenter Dominique AUZIAS et alter Directeur Editorial : Stéphan SZEREMETA les milliers de kilomètres de chemins de randonnées, sillonner Rédaction France : François TOURNIE, Jeff BUCHE, la campagne à vélo sur les voies vertes et véloroutes, vous Grégoire DECONIHOUT et Perrine GALAZKA Rédaction Monde : Patrick MARINGE, Caroline MICHELOT, adonner à des activités nautiques sur l'un des grands lacs Morgane VESLIN, Julien BERNARD et Pierre-Yves SOUCHET du Morvan. -

Motorcycles, Spares and Memorabilia Bicester Heritage | 14 - 16 August 2020

The Summer Sale | Live & Online Including The Morbidelli Motorcycle Museum Collection Collectors’ Motorcycles, Spares and Memorabilia Bicester Heritage | 14 - 16 August 2020 The Summer Sale | Live & Online Including The Morbidelli Motorcycle Museum Collection Collectors’ Motorcycles, Spares and Memorabilia Hangar 113, Bicester Heritage, OX26 5HA | Friday 14, Saturday 15 & Sunday 16 August 2020 VIEWING SALE NUMBER MOTORCYCLE ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES In light of the current government 26111 ON VIEW AND SALE DAYS Monday to Friday 8:30am - 6pm guidelines and relaxed measures +44 (0) 330 3310779 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 we are delighted to welcome CATALOGUE viewing, strictly by appointment. £30.00 + p&p ENQUIRIES Please see page 2 for bidder All the lots will be on view at Ben Walker information including after-sale Bicester Heritage in our traditional +44 (0) 20 8963 2819 collection and shipment Hangar 113. We will ensure social BIDS ENQUIRIES INCLUDING [email protected] distancing measures are in place, VIEW AND SALE DAYS Please see back of catalogue with gloves and sanitiser available +44 (0) 330 3310778 James Stensel for important notice to bidders for clients wishing to view [email protected] +44 (0) 20 8963 2818 motorcycle history files. Please [email protected] IMPORTANT INFORMATION email: motorcycles@bonhams. LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS The United States Government com or call +44 (0) 20 8963 2817 AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE Bill To has banned the import of ivory to book an appointment. Please email [email protected] +44 (0) 20 8963 2822 into the USA. Lots containing with “Live bidding” in the subject [email protected] ivory are indicated by the VIEWING TIMES line no later than 6pm the day symbol Ф printed beside the Wednesday 12 August before the relevant auction Andy Barrett lot number in this catalogue. -

Toutes Marques Jan

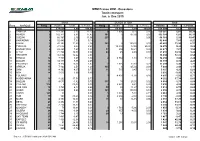

MTM France 2RM - Occasions Toutes marques Jan. à Déc.2019 Motos QUADS et TQM Total Rang MARQUE Rang Volume %Var % Penet. Rang Volume %Var % Penet. Volume %Var % Penet. Total 574 059 6,68 100,00 60 035 5,01 100,00 634 094 6,52 100,00 1 YAMAHA 1 127 387 5,70 22,19 8 1 900 0,21 3,16 129 287 5,61 20,39 2 HONDA 2 102 379 6,81 17,83 161 5 -37,50 0,01 102 384 6,81 16,15 3 SUZUKI 3 66 367 2,16 11,56 203 2 0,00 66 369 2,16 10,47 4 KAWASAKI 4 52 446 7,69 9,14 52 446 7,69 8,27 5 B.M.W. 5 40 399 11,89 7,04 145 6 100,00 0,01 40 405 11,90 6,37 6 PIAGGIO 8 21 046 0,04 3,67 1 15 030 13,50 25,04 36 076 5,24 5,69 7 HARLEY.DAV 6 22 267 7,67 3,88 37 204 34,21 0,34 22 471 7,87 3,54 8 K.T.M. 7 21 786 10,37 3,80 64 45 4,65 0,07 21 831 10,36 3,44 9 TRIUMPH 9 16 094 12,22 2,80 16 094 12,22 2,54 10 KYMCO 12 7 438 4,67 1,30 2 6 792 1,31 11,31 14 230 3,04 2,24 11 DUCATI 10 14 139 8,35 2,46 14 139 8,35 2,23 12 PEUGEOT 11 9 314 -0,58 1,62 7 1 925 12,18 3,21 11 239 1,40 1,77 13 APRILIA 13 7 402 2,51 1,29 145 6 -25,00 0,01 7 408 2,48 1,17 14 SYM 15 4 392 4,37 0,77 11 715 3,47 1,19 5 107 4,25 0,81 15 MBK 14 5 035 -3,95 0,88 5 035 -3,95 0,79 16 POLARIS 3 4 897 -1,05 8,16 4 897 -1,05 0,77 17 HUSQVARNA 16 4 202 17,34 0,73 4 202 17,34 0,66 18 DAELIM 17 4 039 -1,82 0,70 107 15 25,00 0,02 4 054 -1,75 0,64 19 CAN-AM 314 4 -20,00 0,00 4 3 832 4,61 6,38 3 836 4,58 0,60 20 GAS GAS 18 3 723 6,13 0,65 55 89 41,27 0,15 3 812 6,75 0,60 21 GUZZI 19 2 931 8,60 0,51 161 5 150,00 0,01 2 936 8,70 0,46 22 LINHAI 143 37 0,01 5 2 828 5,01 4,71 2 865 4,95 0,45 23 TGB 75 140 -10,26 0,02 6 2 -

(They Know Who They Are). on Your Own You Can Do Nothing, the Future Will Prove It

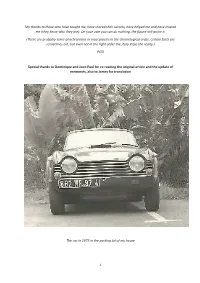

My thanks to those who have taught me, have shared their secrets, have helped me and have trusted me (they know who they are). On your own you can do nothing, the future will prove it. (There are probably some anachronisms or inaccuracies in the chronological order, certain facts are sometimes old, but even not in the right order the story stays the realty.) PGO Special thanks to Dominique and Jean-Paul for re-reading the original article and the update of memories, also to James for translation . The car in 1973 in the parking lot of my house 1 60 years of passion, Mechanics, and how to go from a Citroen C4 to a TRIUMPH TR5 PI with a big M for Mechanics THE PRESAGES. I used to see my Grandfather conscientiously turning the starter handle on his Citroen C4 to free up the engine before starting it, after having checked all the fluid levels. My active participation in this activity was to pass him the rags. Different times would you say ? (well yes, the C4 not that of today, that of 1932 with the thermometer on the radiator and a 'floating' engine) Appreciate the only two graduations of thermometer: Summer temperature and Winter temperature. Some years later, wandering around the mechanics who succeeded one another under the bonnet of his Renault 4CV, which lacked power (what a euphemism) and having thought about it for a long time (!) I decided to get involved. « You need to look at the air filter » Everybody burst out laughing, teasing sniggers by the mechanics. -

Triumph T100SS Motorcycle

CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. All prospective purchasers to register to bid and give in their name, address and telephone number, in default of which the lot or lots purchased may be immediately put up again and re-sold 2. The highest bidder to be the buyer. If any dispute arises regarding any bidding the Lot, at the sole discretion of the auctioneers, to be put up and sold again. 3. The bidding to be regulated by the auctioneer. 4. In the case of Lots upon which there is a reserve, the auctioneer shall have the right to bid on behalf of the Vendor. 5. No Lots to be transferable and all accounts to be settled at the close of the sale. 6. The lots to be taken away whether genuine and authentic or not, with all faults and errors of every description and to be at the risk of the purchaser immediately after the fall of the hammer but must be paid for in full before the property in the goods passes to the buyer. The auctioneer will not hold himself responsible for the incorrect description or authenticity of or any fault or defect in any lot and makes no warranty. 7. To prevent inaccuracy and inconvenience in the settlement of purchases, no lot may be removed either during or after the sale without being previously paid for. 8. If any person neglects or refuses to comply with any of the foregoing conditions, the auctioneer shall be at liberty to resell the lot and any deficiency that may arise in the resale, together with all expenses attending it shall be made good by the defaulter. -

La Grange Aux Motos

HOTEL DES VENTES DE NIMES Pierre CHAMPION, Françoise KUSEL 21, rue de l'Agau - 30000 NÎMES T 04 66 67 52 74 - F 04 66 76 20 96 [email protected] www.ivoire-france.com Communiqué de presse 15 mars 2016 Contact-presse : Sylvie Robaglia +33 (0)6 72 59 57 34 [email protected] La grange recélait une collection inattendue : près de 70 motos, scooters et voitures anciennes Ventes aux enchères le jeudi 14 et le vendredi 15 avril 2016 à 14h00 Le jeudi 14 avril pour les voitures exposition publique et vente sur site Le vendredi 15 avril pour les motos, scooters et vélos : Exposition publique de 9h30 à 11h30 et vente à 14h00 à l’annexe de l’Hôtel des ventes de Nîmes 2750 Route de Montpellier 30000 Nîmes Voici une histoire comme nous les aimons dans le marché de l’art ! Pierre Champion, commissaire-priseur d’Ivoire Nîmes a fait une découverte inattendue lors d’un inventaire. Dans une grange au fond du jardin, près de 70 motos et scooters datant de 1930 à 1960 étaient alignés, chacun préservés par une bâche de protection et portant une pancarte libellant ses marque, cylindrée, millésime et caractéristiques marquantes, sous une épaisse couche de poussière, visiblement parqués là depuis des années. Le collectionneur achetait ces véhicules en l’état et les remettait en fonctionnement. Cet ensemble représente un panorama de la production française motocycliste d'avant 1962 : ALCYON, AUTOMOTO, BERNARDET, BOURRELLY, F.M.C., FAVOR, René GILLET, GNOME-RHONE, GRIFFON, LA FRANCAISE-DIAMANT, LAMBRETTA (montage Français), MAGNAT-DEBON, MANHURIN, MOTOCONFORT, MONET-GOYON, PEUGEOT, RAVAT, TERROT, VESPA-ACMA, sont les marques collectionnées, certaines en plusieurs exemplaires. -

The French Motorcycles

RÉTROMOBILE TRADESHOW PRESS RELEASE DECEMBER 2016 RÉTROMOBILE INTRODUCES A UNIQUE EXHIBITION «THE FRENCH MOTORCYCLES» From the 1871 Perreaux to the 2017 Midual, motorcycles at 100% french will be introduced for the first time at Rétromobile for the 42nd edition of this event. A great opportunity for both the curious and engine enthusiasts to throwback within the outstanding history of the motorcycle trough a beautiful retrospective. THE MOTORCYCLE : A FRENCH PASSION Motorcycles were invented in France and the machines we built dominated the world right at the start of the 20th century. The very first steam- powered velocipedes to be sold were built and patented in 1871 by Louis Guillaume Perreaux. Then very soon after, motorcycles were all the rage. In 1898, the Werner Brothers were credited with the first use of the word Perreaux motorcycle of 1871 «Motocyclette” – the name they used for their first model. © Collection musée du Domaine Terrot, Peugeot or Gnome & Rhône départemental de Sceaux - photo From major manufacturers such as Olivier Ravoire to France’s early craftsman, nearly 1000 brands have seen the light of day; Rétromobile will be bringing together some of the finest truly French inventions at this year’s show. Museums, collectors, motorcycle drivers and historians will all be sharing their love of these machines. The central exhibition area and the club area will feature thirty or so unique models – from the first to the very latest French motorcycles. They’ll include the 1871 Louis-Guillaume Perraux “Moto bicyclette”, Jonghi 350 of 1934 Louis Blériot’s 1920 invention, the Peugeot 500 two-cylinder which won the 1927 Grand Prix, the 1939 amphibious Simca-Sevitame, the machines on which Georges Monneret set his records, the 1934 Jonghi 350 and the 1952 Koehler-Escoffier 1000, the 1957 Taon Derny designed by Roger Tallon.. -

Acc Essoires· · Pour Motos

...'...=================================================== ======:.: ACC ESSOIRES· · POUR MOTOS. VElOMOTEURS & CYClOMOTEURS NOUVEAUTE FRANCE DE CLUB N ' 48 - SIEGE A RRIERE A SUSPENSION REGLA BLE Dessus ca o ut chou c doub le feuilles - Larg. 320 - Lo ng. 240 N ° 5 - SIEGE ARRIER E A S U :;PE N SIO N REGLABLE Tein tes hav a ne , nc ire, gr ise, ve rre , bl e ue Raf. G RAND MODELE Sur po rt e-ba gages Prix 3 ,500 TERROTDessus cco utVENDUcho uc do ubl e feuilles - Lc rg , 370 - Lo ng. 300 N ° 48 t el' - Speci al VESPA vert « 3.500 Tein t es hovo ne , noi re, gr ise , ve rte , bleue Ra f. « VESPA 55 sons poi gnee N " 5 - Mon ta ge sur po rt e- ba ga ges Prix 3.800 LE N ° 7 - Special VESPA ve r t « 3 .800 lvolr e et ve r t {( 3. 285 « VESPA 55 sa ns po ign ec « LAMBRETTA « 3.500 ÊTRE ivoir e e t ve rt « 3.585 Mob y-Scoote r M B ivo ire et gr is PAR« 3 .500 N "8 « LAMBRETTA « 3.800 N ) 49 - SIEGE ARRIERE A SUSPENSION REGLABLE Sim ple fe uille - Dessus 300 x 320 - Noir o u ha vo ne . P"ix : 3.500 N ' 50 - SIEGE ARRIEREPEUT sim pl e feuille. G ra nd modele 300 .<330 . Ga rn it ur e no ire a u hav a ne . Pr ix : 3.800 N ' 48 bis - S IEGE ARRIERE d oubl e feuill es. Mont a ge sur gorde bouc la rge .