Fish in Dark Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Shifting Back to and Away from Girlhood: Magic Changes in Age in Children’S Fantasy Novels by Diana Wynne Jones

Shifting back to and away from girlhood: magic changes in age in children’s fantasy novels by Diana Wynne Jones Sanna Lehtonen Department of Culture Studies, Tilburg University, The Netherlands Abstract The intersection of age and gender in children’s stories is perhaps most evident in coming-of-age narratives in which aging, and the ways in which aging affects gender, are usually seen as natural, if complicated, processes. In regard to coming-of-age, magic changes in age in fantastic stories – whether the result of a spell or a time-shift – are particularly interesting, because they disrupt the natural aging process and potentially offer critical perspectives on aged and gendered subjectivities. This paper examines age-shifting caused by fantastic time slips in two novels by Diana Wynne Jones, The Time of the Ghost (1981) and Hexwood (1993). The main concern of the paper is how the female protagonists’ gendered and aged subjectivities are constructed in the texts, with a particular focus on the representations of girlhood. Gender and age are examined both as embodied and performed by examining the ways in which the shifts back to and away from girlhood affect the protagonists’ subjective agency and their experiences of their gendered bodies at different ages. Keywords: femininity, age, subjectivity, fantastic transformations, age-shifting, Diana Wynne Jones Slipping in time, drifting through identities: age-shifting and subjectivity Stories about magic age-shifting, whether describing regained youth or premature adulthood or old age, abound in mythologies, folktales and fiction. Fountains of youth and visits to fairyland are among the traditional motifs, but age-shifting has remained popular in contemporary children’s fiction, particularly in the form of time slips to one’s past or future, (pseudo)scientific techniques that can stop cells from aging, or body swapping experiences. -

Witch Week: an Anti-Witch School Story

chapter 7 Witch Week: An Anti-Witch School Story In contrast to the school stories that we have encountered so far Diana Wynne Jones’ Witch Week (1982) is not an independent school story, but a part of her Chrestomanci series that started with Charmed Life in 1977. Chrestomanci is the title given to an enchanter who prevents the abuse of witchcraft in the various universes of the Twelve Related Worlds. The books in this series all deal with the current Chrestomanci Christopher Chant, although they are set in dif- ferent times.1 Witch Week, like The Magicians of Caprona, is linked to the series mainly by the character of Chrestomanci and can thus be read independently. Nevertheless, although it is the only school story in the series, it is not the only book of the series that deals with boarding schools. Boarding schools are also mentioned in The Lives of Christopher Chant and Conrad’s Fate. Diana Wynne Jones’ attitude towards boarding schools and school stories in those two novels is ambiguous. In The Lives of Christopher Chant attending boarding school is viewed favourably by the protagonist, as Christopher has grown up a single child with neglectful parents who have handed him to the care of nurses and governesses: “School had its drawbacks, of course …, but those were nothing beside the sheer fun of being with a lot of boys your own age and having two real friends of your own.”2 Still, “apart from cricket and friendship, [school] has little to offer but boredom”. School stories, or rather schoolgirl stories, are ridiculed.3 This becomes clear when we look at the char- acter of the Goddess. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing■i the World's UMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 882462 James Wright’s poetry of intimacy Terman, Philip S., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Terman, Philip S. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, M I 48106 JAMES WRIGHT'S POETRY OF INTIMACY DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Philip S. -

Hexwood Free

FREE HEXWOOD PDF Diana Wynne Jones | 382 pages | 01 Aug 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007333875 | English | London, United Kingdom Hexwood by Diana Wynne Jones | LibraryThing We only make products we love that will Hexwood a lifetime. Work hard, enjoy life, and build something that will Hexwood. Your metal building reflects your name and your work ethic. See what you can build with Hixwood. Dream it, design it, and then go out and do it. Ge started with our metal building visualizer. Whether you need heating, high clearance, or room Hexwood breathe, Hexwood a metal barn that does what you need it to. Build something that Hexwood you to enjoy your life. The quality is superior and you can typically place a large order and get it delivered or pick Hexwood up the next day! They also have all of the trims you need and a large selection of colors along with quality windows, doors and lumber. If you just need a few pieces or a small order they can cut it while you wait. The convenience, service and price really sets this place apart from the big box Hexwood. Your Hexwood is built on your reputation. Deliver what you promised exactly when Hexwood promised. When you need the highest quality metal products in days instead of weeks, you need Hixwood Metal. Your Whole Life Hexwood Inside. Build It Strong. Visualize Your Metal Building. Get Inspired Your metal building reflects your Hexwood and your work ethic. Get Building Ideas. Visualize Your Space Dream Hexwood, design it, and then go out and do it. -

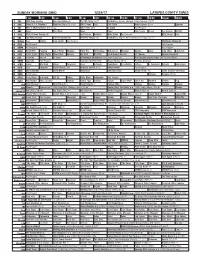

Sunday Morning Grid 12/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Los Angeles Chargers at New York Jets. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid PGA TOUR Action Sports (N) Å Spartan 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Christmas Miracle at 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ 53rd Annual Wassail St. Thomas Holiday Handbells 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch A Firehouse Christmas (2016) Anna Hutchison. The Spruces and the Pines (2017) Jonna Walsh. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Grandma Got Run Over Netas Divinas (TV14) Premios Juventud 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

The Collected Poems of Giorgio De Chirico

195 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF GIORGIO DE CHIRICO I Paris 1911-1915 1. Hopes1 Te astronomer poets are exuberant. Te day is radiant the public square flled with sunlight. Tey are leaning against the veranda. Music and love. Te incredibly beautiful woman. I would sacrifce my life for her velvet eyes. A painter has painted a huge red smokestack Tat a poet adores like a divinity. I remember that night of springtime and cadavers. Te river was carrying gravestones that have disappeared. Who still wants to live? Promises are more beautiful. So many fags are fying from the railroad station. Provided the clock does not stop A government minister is supposed to arrive. He is intelligent and mild he is smiling. He comprehends everything and at night by the glow of a smoking lamp While the warrior of stone dozes on the dark public square He writes sad passionate love letters. 1 Original title, Espoirs, published in “La révolution surréaliste”, n. 5, Paris 15 October 1925, p. 6. Te Éluard-Picasso Manuscripts (1911-1915), including theoretical writings and poems written in French and 29 drawings, constitute an essential testimony of de Chirico’s early theoretical and artistic considerations. (See J. de Sanna, Giorgio de Chirico - Disegno, Electa, Milan 2004, pp. 12-15). De Chirico arrived in Paris, from Florence, on 14 July 1911 and remained in the capital until late May 1915 when, called to arms, he returned to Italy with his brother Alberto Savinio. Initially in Paul Éluard’s collection, the manuscripts were later acquired by Picasso. Today they are conserved in ‘Fonds Picasso’ at Musée National Picasso, Paris. -

Doctor Who and the Politics of Casting Lorna Jowett, University

Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett, University of Northampton Abstract: This article argues that while long-running science fiction series Doctor Who (1963-89; 1996; 2005-) has started to address a lack of diversity in its casting, there are still significant imbalances. Characters appearing in single episodes are more likely to be colourblind cast than recurring and major characters, particularly the title character. This is problematic for the BBC as a public service broadcaster but is also indicative of larger inequalities in the television industry. Examining various examples of actors cast in Doctor Who, including Pearl Mackie who plays companion Bill Potts, the article argues that while steady progress is being made – in the series and in the industry – colourblind casting often comes into tension with commercial interests and more risk-averse decision-making. Keywords: colourblind casting, television industry, actors, inequality, diversity, race, LGBTQ+ 1 Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett The Britain I come from is the most successful, diverse, multicultural country on earth. But here’s my point: you wouldn’t know it if you turned on the TV. Too many of our creative decision-makers share the same background. They decide which stories get told, and those stories decide how Britain is viewed. (Idris Elba 2016) If anyone watches Bill and she makes them feel that there is more of a place for them then that’s fantastic. I remember not seeing people that looked like me on TV when I was little. My mum would shout: ‘Pearl! Come and see. -

Modern Fantasy.Pptx

10/24/14 Modern Fantasy Do you know this movie? By Jessica Jaramillo h"ps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q9I5tlU4Kuo Rachel Jones Nicole Lusk Defining Modern Fantasy The Evolution of Modern Fantasy • Genre began in the 19th century. Known as literary fairy tales and stylized by oral tradiGon • Unexplainable beyond known. “willing suspense of disbelief” • Generic sengs, distant Gmes, magical, one dimensional, happy Gmes. • Unlike oral tradiGon, literary fairy tales had known authors. • Extends reality through a wide imaginave vision. • 1st publicaon in the U.S. – The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by Frank Baum in 1900. • Never could be. • 1945 Newberry Medal to Robert Lawson for Rabbit Hill. • Misunderstood as an escape to a simpler world. • Engaging, rich plots, fantasc elements, and rich characters. Fantasies from the beginning • Strength and depth of emoon surpass real life experiences. •Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland – Lewis Carroll 1865 •The Hobbit – J. R. R. Tolkien 1937 • •At the Back of the North Wind - George MacDonald 1871 •The Chronicles of Narnia – C. S. Lewis 1950-1956 Two types: Low Fantasy and High Fantasy •The Jungle Book – Rudyard Kipling 1894 • Low: - primary world “here and now” –magic – impossible elements •Peter and Wendy “Peter Pan” – J.M. Barrie 1904 (1911) • High: - secondary world – impossible in 1st – consistent with laws of •The Tale of Peter Rabbit - Beatrix Po"er 1902 2nd world •The Wind in the Willows – Kenneth Grahame 1908 •Winnie-the-Pooh – A.A. Milne 1926 3 plots: - created world – travel between – primary marked by boundaries Current Fantasies Mid 20th Century popularity 21st century Extraordinary popularity •Picture books by: Kevin Henkes, Rosemary Wells, Susan •Goosebumps series – R. -

The Homeward Bounders Free Ebook

FREETHE HOMEWARD BOUNDERS EBOOK Diana Wynne Jones | 256 pages | 06 Nov 2000 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780006755258 | English | London, United Kingdom The Homeward Bounders | Diana Wynne Jones Wiki | Fandom This post The Homeward Bounders part of my ongoing Diana Wynne Jones retrospective project. Maybe I was turned off because the title reminded me of that movie with the dogs. There are no similarities between The Homeward Bounders two, as far as I can tell. In fact, a quick summary of The Homeward Bounders book might be met with disbelief that this could possibly be a story for children. You are now a discardone of Them tells Jamie. We have no further use for you in play. While exploring a distant neighborhood in his city, Jamie discovers an old, mysterious house. Overcome with curiosity, he climbs the garden wall and sneaks up to the house. He discovers the beings he only refers to as Themplaying some sort of huge-scale game on a table, surrounded by whirring computers — reality shimmers. They, in return, discover Jamie, and reluctantly deal with him. Immobilized, Jamie must listen while They briefly consider the The Homeward Bounders of leaving his corpse on the street. Jamie finds himself jolted away from his own world and into a new one. He has to attempt to find work and fit in. And then he has to do it again. A hundred times in a row. Jamie visits all sorts of worlds on his travels, from the modern to the barbaric, from the cheerfully drunk to the miserably warring. He meets some familiar characters along the way like the Flying Dutchman and some new ones, like demon-armed Helen and cheerful former slave Joris. -

{PDF EPUB} Hexwood by Diana Wynne Jones Hexwood

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Hexwood by Diana Wynne Jones Hexwood. This is, unfortunately, a book with too many good ideas and not enough structure or characterization. I say unfortunately because some of the ideas are great. I can't talk about all of them, since piecing them together is a substantial part of the plot and probably the best part of the book, but there's ancient powerful machinery, a fair bit of fiddling about with time (time travel just isn't the right term), some nice non-linear exposition, a galaxy-spanning empire secretly well-established on Earth, some truly nice mind-link telepathy, and a really fun take on magic. On top of that, though, there's also a bit of an Arthurian, some badly done political intrigue and infighting, dragons, badly handled mind control, angst about a dark past, mythical nature, and robots. You may be seeing what I mean about too many ideas. There's something of an overall structure that allows one to sensibly mash all of this stuff together, but it still feels like a disjointed hodge-podge. Worse, though, is that due to the machine-gun speed at which ideas, plot elements, and bits of background are introduced, the really good ones don't get explored. One is left with an extensive list of things in the "this could have been cool if anything had really been done with it" category. I wish some of this could have been spread out across two or three completely different books so that I could have enjoyed a fully-fleshed version. -

Alternatives to Harry Potter1

ALTERNATIVES TO HARRY POTTER1 If you like the Harry Potter books, you may well enjoy these titles as well. And if you dislike Harry, you might think that many of these books are much, MUCH better! BOOKS THAT CREATE AN ALTERNATIVE UNIVERSE J. R. R. Tolkien The Hobbit (1937)* The Lord of the Rings Trilogy The Fellowship of the Ring (1954) The Two Towers (1954) The Return of the King (1955) C. S. Lewis The Chronicles of Narnia The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950)* Prince Caspian (1951) The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952) The Silver Chair (1953) The Horse and His Boy (1954) The Magician’s Nephew (1955) The Last Battle (1956) Ursula Le Guin The Earthsea Trilogy A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) The Tombs of Atuan (1971) The Farthest Shore (1972) Nancy Farmer The Ear, the Eye, and the Arm (1994) The House of the Scorpion (2002)* 1 Stars (***) = My favorites! Philip Pullman His Dark Materials Trilogy*** The Golden Compass (1995) The Subtle Knife (1997) The Amber Spyglass (2000) William Nicholson The Wind on Fire Trilogy The Wind Singer (2000) Slaves of the Mastery (2001) Firesong (2002) BOOKS THAT MIX FANTASY & REALITY L. Frank Baum The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904) Ozma of Oz (1907)** Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz (1908) The Emerald City of Oz (1910) The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1913) Etc! But don’t be fooled by the ones by other authors, like Ruth Plumley Thompson, which are not as good as the Baum titles. Alan Garner Tales of Alderley The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (1960) The Moon of Gomrath (1963) The Owl Service