Listen and Learn TED Talks Reach Millions Around the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“I Don't Care for My Other Books, Now”

THE LIBRARY University of California, Berkeley | No. 29 Fall 2013 | lib.berkeley.edu/give Fiat Lux “I don’t care for my other books, now” MARK TWAIN’S AUTOBIOGRAPHY CONTINUED by Benjamin Griffin, Mark Twain Project, Bancroft Library Mark Twain’s complete, uncensored Autobiography was an instant bestseller when the first volume was published in 2010, on the centennial of the author’s death, as he requested. The eagerly-awaited Volume 2 delves deeper into Twain’s life, uncovering the many roles he played in his private and public worlds. Affectionate and scathing by turns, his intractable curiosity and candor are everywhere on view. Like its predecessor, Volume 2 mingles a dia- ry-like record of Mark Twain’s daily thoughts and doings with fragmented and pungent portraits of his earlier life. And, as before, anything which Mark Twain had written but hadn’t, as of 1906–7, found a place to publish yet, might go in: Other autobiographies patiently and dutifully“ follow a planned and undivergent course through gardens and deserts and interesting cities and dreary solitudes, and when at last they reach their appointed goal they are pretty tired—and they The one-hundred-year edition comprises what have been frequently tired during the journey, too. could be called a director’s cut, says editor Ben But this is not that kind of autobiography. This one Griffin. “It hasn’t been cut to size or made to fit is only a pleasure excursion. the requirements of the market or brought into ” continued on page 6-7 line with notions of public decency. -

Rethinking the Participatory Web: a History of Hotwired's “New Publishing Paradigm,” 1994–1997

University of Groningen Rethinking the participatory web Stevenson, Michael Published in: New Media and Society DOI: 10.1177/1461444814555950 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2016 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Stevenson, M. (2016). Rethinking the participatory web: A history of HotWired's 'new publishing paradigm,' 1994-1997. New Media and Society, 18(7), 1331-1346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814555950 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

Rethinking the Participatory Web Final

Preprint version of Stevenson, Michael. 2014. “Rethinking the Participatory Web: A History of HotWired’s ‘New Publishing Paradigm,’ 1994–1997.” New Media & Society, October. doi: 10.1177/1461444814555950. Title Rethinking the participatory web: A history of HotWired’s ‘new publishing paradigm,’ 1994-1997. Author Michael Stevenson University of Amsterdam [email protected] Abstract This article critically interrogates key assumptions in popular web discourse by revisiting an early example of web ‘participation.’ Against the claim that Web 2.0 technologies ushered in a new paradigm of participatory media, I turn to the history of HotWired, Wired magazine’s ambitious web-only publication launched in 1994. The case shows how debates about the value of amateur participation vis-à-vis editorial control have long been fundamental to the imagination of the web’s difference from existing media. It also demonstrates how participation may be conceptualized and designed in ways that extend (rather than oppose) 'old media' values like branding and a distinctive editorial voice. In this way, HotWired's history challenges the technology-centric change narrative underlying Web 2.0 in two ways: first, by revealing historical continuity in place of rupture, and, second, showing that 'participation' is not a uniform effect of technology, but rather something constructed within specific social, cultural and economic contexts. Keywords web history, participation, Web 2.0, cyberculture, digital utopianism, Wired !1 Introduction In the mid-2000s, a series of popular accounts celebrating the web’s newfound potential for participatory media appeared, from Kevin Kelly’s (2005) proclamation that active audiences were performing a ‘bottom-up takeover’ of traditional media and Tim O’Reilly’s (2005) definition of ‘Web 2.0’ to Time’s infamous 2006 decision to name ‘You’ as the person of the year (Grossman, 2006). -

Download Transcript

MoS Episode Transcript: Reid Hoffman MATTHEW MERCER: After days of tumultuous travel through harsh rain and biting winds, you finally ascend the cold, granite steps outside the gates of the mountain city of Grimgoleir. Glancing amongst your comrades from under your soaked cloak, you reach out for the heavy brass knocker and hammer the massive stone door three times. REID HOFFMAN: That's Matthew Mercer, creator of the hit Dungeons and Dragons web series called Critical Role. And right now, Matthew is your Game Master — the central storyteller in a game of Dungeons & Dragons. Which means: Your fate is in his hands. Listen carefully, because he has a question for you. One that could mean the difference between heroic success and epic failure. MERCER: A stillness takes the air, the sounds of rain almost fading as the door slowly opens, releasing the stench of death from within the chambers. Your eyes catch nearby torch light inside, and what appears to be an armored ghoul, slick with fresh blood as it drops some errant piece of a recent kill, and turns its head towards you with a growl. What would you like to do? VOICE: I’m going to stab that nasty ghoul with my magical scimitar and save the day! Come on, lucky sevens! Oh come on — a one? MERCER: Oh, you quickly draw your scimitar, the cold metal warming with the flames that magically dance across its surface as you rush the undead beast, but in your haste, you failed to notice the body on the ground hidden in shadow, catching your foot as your stumble forward, barely catching yourself before you come to stop right at the feet of the now-grinning ghoul. -

Screening TED: a Rhetorical Analysis of the Intersections of Rhetoric, Digital Media, and Pedagogy

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 Screening TED: A rhetorical analysis of the intersections of rhetoric, digital media, and pedagogy Joseph Alan Watson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Watson, Joseph Alan, "Screening TED: A rhetorical analysis of the intersections of rhetoric, digital media, and pedagogy" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2544. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2544 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SCREENING TED: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE INTERSECTIONS OF RHETORIC, DIGITAL MEDIA, AND PEDAGOGY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Joseph A. Watson B.A., The University of Memphis, 1998 M.A., The University of Memphis, 2003 December 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The decision to enter a doctoral program is agreeing to train for and complete an intense marathon. During my training, I had the good fortune to work with some amazingly talented and supportive people at LSU. First, thank you to my best friend and wife, Shalika, for supporting and believing in this dream. You have been the backbone and inspiration for this entire journey. -

Philip G. Zimbardo

PHILIP G. ZIMBARDO An Oral History conducted by Daniel Hartwig STANFORD HISTORICAL SOCIETY ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM Stanford University ©2017 2 Ferne Millen Photography Philip G. Zimbardo, 2015 3 4 Contents Publisher’s Note p. 9 Introduction p. 11 Abstract p. 13 Biography p. 15 Part One—May 9, 2016 p. 19 Ancestors, childhood, and family life in New York Temporary move to California High school classmate Stanley Milgram Milgram’s obedience experiments and career Stanford Prison Experiment Undergraduate education Social activism Part Two—September 1, 2016 p. 67 Graduate study at Yale Teaching at New York University Research on deindividuation Social activism Harlem Summer Project Vietnam War Malcolm X International European Social Psychology Summer Program Part Three—September 1, 2016 p. 97 Columbia University Joining Stanford faculty 5 Stanford Psychology Department Resident faculty at Cedro Teaching methods Psychology & Life Faculty and colleagues 1960s, activism, Vietnam War Social Psychology in Action Birth of the Stanford Prison Experiment Stanford Shyness Project Part Four—December 9, 2016 p. 145 End of the Stanford Prison Experiment Stanford Shyness Clinic Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory Mind control Madness Part Five—December 9, 2016 p. 163 Discontinuity and paranoia Discovering Psychology Teaching psychology at Stanford American Psychological Association 9/11, terrorism Abu Ghraib Retirement The Lucifer Effect Heroic Imagination Project Part Six—March 12, 2017 p. 207 Man Interrupted, A Boy Disconnected Heroic Imagination Project Discovering Psychology 6 Recruitment of minorities and women Mentoring graduate students Applied psychology Program in Human Biology Part Seven—March 12, 2017 p. 245 Music Department, Stanley Getz Activism Psi Chi, the Psychology Honor Society Reflections and accomplishments Curriculum Vitae p. -

About the Technical Reviewer About the Cartoonist About the Author

00 2069_FM 5/19/03 4:37 PM Page xii xii | the unusually useful web book about the author June Cohen has been a leading developer of web sites and mul- timedia for more than a decade. In 1991, she led the Stanford University team that developed the world’s first networked mul- timedia publication. Then, in 1994, she helped launch HotWired.com, the first commercial content site (and spin-off of Wired Magazine). While at HotWired, she founded Webmonkey.com, the much-loved web-developer’s site used by millions. Later, as HotWired’s VP of Content, she played a key role on a range of innovative sites, from Animation Express to the HotBot search engine. June holds a BA from Stanford, where she was editor of The Stanford Daily. After years in San Francisco, she now lives in New York City, where she occasionally talks about things other than the web. about the technical reviewer Steve Sanchez is the founder and CEO of iNexus.com, a Los Angeles–based firm that consults, builds, and promotes Internet solutions for business. Over the past 10 years, he has worked with leading companies in industries such as travel, medicine, and publishing, creating sites that work for both owners and users. A long-time evangelist for strengthening the online user’s experience, Steve is a “raving fan” of database- driven web sites, web communities for business, and technologies such as dynamic Flash, VR tours, Active Server Pages, and Microsoft’s .NET. He enjoys photography, travel, sailing, and scuba diving. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife and four children. -

Transworld Non-Fiction Jul-Dec 2021

NON-FICTION CATALOGUE JULY - DECEMBER 2021 1 Rebuild How to Do Business Better Mary Portas Since the pandemic, many businesses have gone under. But some businesses are positively buoyant, despite the odds being stacked against them. Why is that? Rebuild is a life raft, a vital guide to how we reset and build back better. Over the past thirty years the business of what we buy has been dominated by the biggest, fastest and cheapest. But those values no longer resonate. We've come to realize that more doesn't equal better. Good business is now about putting people and planet before profit. The post-pandemic era is all about care, respect and understanding the implications of what we're doing. This 'Kindness Economy' is a new value system that means in order to thrive businesses must rediscover their true purpose, and fuse brand magnetism with social progress. We're not simply consuming anymore, we're buying into something. Which means that, whether physical or digital, the most important space that any business can now occupy is the space in peoples' hearts. Full of expert insight, Rebuild is about resetting the dial. It gives businesspeople pause for thought and the practical tools to build back post- pandemic and speaks to anyone who votes with the pound in their pocket, who with social progress in mind wants to spend their money differently and better. Mary Portas is one of the UK's most high-profile businesswomen. After making her name transforming Harvey Nichols into London's sexiest fashion destination, Mary July 2021 launched her own retail consultancy, Portas, which works with 9781787635166 clients ranging from Louis Vuitton to Sainsbury's. -

The High Price of Silence Analyzes Management’S Viewpoints, Pressures, and Privileges Regarding Time Off

The High Price of Analyzing the Business Implications of an Under-Vacationed Workforce It is the punch-line to the clichéd, “What’s your biggest weakness?” interview question: “I work too hard. I care too much.” But somewhere along the way, the joke became prophecy. The inability to take time off has become one of America’s greatest work culture failings, defining hard work quantitatively not qualitatively, epitomized by the 658 million vacation days workers left unused last year. Americans consistently assert their vacation time is important, yet the majority leave days unused each year. Who is to blame? The strongest influencer over taking time off is not workers themselves: it is their bosses. The High Price of Silence analyzes management’s viewpoints, pressures, and privileges regarding time off. We must better understand how to create meaningful solutions that work for individual employees and companies. The vibrancy and success of the American business community depends on it. The High Price of Silence 1 GfK conducted an online survey using the GfK KnowledgePanel® from January 20-February 16, 2016 with 5,641 American workers, age 18+, who work more than 35 hours a week and receive paid time off from their employer. GfK’s KnowledgePanel® is the only large-scale online panel based on a representative random sample of the U.S. population. This report looks at a subset of this data, including 1,184 respondents who have managerial responsibilities and 312 managers who are executive and senior leaders. Throughout the report, the data will be referenced according to the following definitions: • Non-manager employees: respondents who are not involved in decision-making and do not have managerial responsibilities. -

No. 46, March 2016

No. 46, March 2016 Editors: Professor Dr. Horst Drescher † Lothar Görke Professor Dr. Klaus Peter Müller Ronald Walker Table of Contents Editorial 2 Comments on the Referendum, the General Election, Land Reform & Feudalist Structures - Jana Schmick, "What the Scots Wanted?" 4 - Katharina Leible, "General Election and Poll Manipulation" 8 - Andrea Schlotthauer, "High Time to Wipe Away Feudalist Structures – 10 Not Only in Scotland" Ilka Schwittlinsky, "The Scottish Universities' International Summer School – 11 Where Lovers of Literature Meet" Klaus Peter Müller, "Scottish Media: The Evolution of Public and Digital Power" 13 New Scottish Poetry: Douglas Dunn 39 (New) Media on Scotland 40 Education Scotland 58 Scottish Award Winners 61 New Publications April 2015 – February 2016 62 Book Reviews Klaus Peter Müller on Demanding Democracy: The Case for a Scottish Media 75 Klaus Peter Müller on the Common Weal Book of Ideas. 2016 – 21 83 Kate McClune on Regency in Sixteenth-Century Scotland 91 Ilka Schwittlinsky on Tartan Noir: The Definitive Guide to Scottish Crime Fiction 92 Conference Reports (ASLS, Stirling, July 2015, by Silke Stroh and Nadja Khelifa) 95 Conference Announcements 100 In Memory of Ian Bell 103 Scottish Studies Newsletter 46, March 2016 2 Editorial Dear Readers, Here is the special issue on 'Scottish Media' projected in our editorial last year. Media are so important, so hugely contested, such a relevant business market, and so significant for peo- ple's understanding of reality that this Newsletter is a bit more voluminous than usual. It also wants to challenge you in important ways: media reflect the world we live in, and this issue points out the dangers we are facing as well as the enormous relevance of your active partici- pation in making our world better, freer, more democratic. -

Famed TED Talks Available in Multiple Languages 13 May 2009, by Glenn Chapman

Famed TED talks available in multiple languages 13 May 2009, by Glenn Chapman "There is something magical about seeing all these languages on the same page that makes the world smaller and bigger at the same time," said executive producer of TED media June Cohen. A TED roster of past speakers includes Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, rock star Bono, novelist Isabel Allende, and former US vice president Al Gore. The organizers of the famed annual TED conferences on TED Talks have reportedly been viewed more than Wednesday began making the thought-provoking lectures by giants of technology, science and the arts 100 million times by more than 15 million online available in dozens of languages. visitors. "A Web-empowered revolution in global education is under way," Anderson said. The organizers of the famed annual TED conferences on Wednesday began making the "We're not far from the day when anyone on Earth thought-provoking lectures by giants of technology, can directly access the world's great teachers science and the arts available in dozens of speaking to them in their own language. How cool languages. is that?" Online video of the talks at the annual Technology Volunteers from the TED community translate Education Design (TED) conferences devoted to approved transcripts of talks, creating multi-lingual "ideas worth spreading" are being translated for subtitles and full copies of the texts to accompany the world to hear with the help of volunteers. online videos. "TED's mission is to spread good thinking globally, Clicking on words in on-screen transcripts takes and so it's high time we began reaching out to the viewers instantly to corresponding portions of 4.5 billion people on the planet who don't speak videos. -

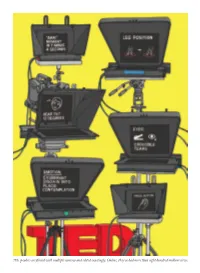

TED Speakers Are Filmed with Multiple Cameras and Edited Exactingly

TED speakers are filmed with multiple cameras and edited exactingly. Online, they’ve had more than eight hundred million views. TNY—2012_07_09&16—PAGE 68—133SC.—livE ArT r22355_rD3 amERicaN chronicLEs LisTEN aNd leaRN TED Talks reach millions around the world. How has a conference turned ideas into an industry? by naTHan heller ’d like to begin with a story. On a graduate work focusses on collective growing, best-educated, and wealthiest bright late-February afternoon, in cognition and social networks, saw his creative communities in America. (Ad- LongI Beach, California, Lior Zoref, an appearance in this company as an ar- mission to the Long Beach conference Israeli Ph.D. student, climbed onstage rival. Last April, he had signed up for starts at seventy-five hundred dollars, to rehearse what he called “the talk of the conference’s first public auditions, not including the hotel; tickets are my life.” It was the second full day of the promising a crowd-sourced talk, on the available by invitation, or through an TED ideas conference, and in the lobby idea that a group of networked minds application that includes both essays outside the theatre doors more than a can shape a better product than an in- and references.) And, although “TED” thousand men and women milled and dividual imagination. After putting out stands for Technology/Entertainment/ gammed and ate lunch in the winter sun. the word on Twitter, Facebook, and his Design, the conferences have recently Zoref was nervous. He had spent the past blog (“Ideas for other questions or sub- skewed toward the first part of the trip- few months preparing with an athlete’s jects I should address?”), he’d received tych.