'Ga, Ga, Ooh-La-La': the Childlike Use of Language in Pop-Rock Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Action of God's Love

Christ Episcopal Church, Valdosta “The Action of God’s Love” (2 Corinthians 4:14-5:1) June 6, 2021 Dave Johnson In the Name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Apostle Paul’s Second Letter to the Corinthians is far and away his most vulnerable letter. He does not water down the realities of his suffering as an apostle of the gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ—as he writes: Five times I have received the forty lashes minus one. Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I received a stoning. Three times I was shipwrecked; for a night and a day I was adrift at sea; on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from bandits, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers and sisters; in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, hungry and thirsty, often without food, cold and naked. And besides other things, I am under daily pressure because of my anxiety for all the churches. Who is weal, and I am not weak? (2 Corinthians 11:24-29). Not only did Paul suffer all these things in his apostolic ministry, he also suffered in his personal life, especially with what he dubbed his “thorn in the flesh”: “Therefore, to keep me from being too elated, a thorn was given me in the flesh, a messenger of Satan to torment me, to keep me from being too elated.” Paul does not reveal what this specific “thorn in the flesh” was, though there are many theories about it, but he does reveal what he did about it: “Three times I appealed to the Lord about this, that it would leave me, but he said to me, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness’” (2 Corinthians 12:7-9). -

Sammy Strain Story, Part 4: Little Anthony & the Imperials

The Sammy Strain Story Part 4 Little Anthony & the Imperials by Charlie Horner with contributions from Pamela Horner Sammy Strain’s remarkable lifework in music spanned almost 49 years. What started out as street corner singing with some friends in Brooklyn turned into a lifelong career as a professional entertainer. Now retired, Sammy recently reflected on his life accomplishments. “I’ve been inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame twice (2005 with the O’Jays and 2009 with Little (Photo from the Classic Urban Harmony Archives) Anthony & the Imperials), the Vocal Group Hall of Fame (with both groups), the Pioneer R&B Hall of Fame (with Little An- today. The next day we went back to Ernie Martinelli and said thony & the Imperials) and the NAACP Hall of Fame (with the we were back together. Our first gig was to be a week-long O’Jays). Not a day goes by when I don’t hear one of the songs engagement at the Town Hill Supper Club, a place that I had I recorded on the radio. I’ve been very, very, very blessed.” once played with the Fantastics. We had two weeks before we Over the past year, we’ve documented Sammy opened. From the time we did that show at Town Hill, the Strain’s career with a series of articles on the Chips (Echoes of group never stopped working. “ the Past #101), the Fantastics (Echoes of the Past #102) and The Town Hall Supper Club was a well known venue the Imperials without Little Anthony (Echoes of the Past at Bedford Avenue and the Eastern Parkway in the Crown #103). -

THE CARS of Will.I.Am WIN a RANGE ROVER EVOQUE with BRITAX

MAX MPG MERCEDES IDRIS ELBA & JAG XE £5K MINI COOPER FRILLY SEAT Mii THE CARS OF will.i.am WIN A RANGE ROVER EVOQUE WITH BRITAX freecarmag.co.uk 1 GET YOUR SMART FINGER OUT AND FIND THE RIGHT CAR FOR YOU Find 1000s of history checked cars near you Untitled-1 1 03/03/2015 09:14:35 Smart finger - Smart Search - 230x280.indd 1 27/02/2015 16:48 GET YOUR SMART FINGER OUT AND ISSUE 01 / 2015 FIND THE RIGHT CAR FOR YOU this week elcome to Free Car Mag. We are Wdifferent to other car magazines, not only because we are actually free, but free to think and do things differently. At Free Car Mag we are committed to bringing you stories, pictures and information that you will find genuinely useful, amusing, provocative, odd, silly and fun. Free Car Mag will tell you what’s going on in the four wheeled (and sometimes two-wheeled) world without getting all precious and pretentious about it. This is a magazine for you so we want to know what you think. Tell us what we can do better and ask us questions. Do that via our brilliant website which will also help you value a car, buy another and how to run one for less. Free Car Mag love cars and driving them, but we don’t believe it has to be complicated. No one really needs to know how to change a water pump, unless they really want to. Free Car Mag promises never to use any boring technical terms and if you spot the word crankshaft in these pages we will send you a cheque for £100. -

Das Genie, Das Ich Nicht Vermarkten Wollte

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Tandem Das ungleiche Paar Paul Simon und Art Garfunkel werden 75 Von Christiane Rebmann Sendung: 04.11.2016 um 19.20 Uhr Redaktion: Bettina Stender Sprecher: Peter Binder Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Service: SWR2 Tandem können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de oder als Podcast nachhören: http://www1.swr.de/podcast/xml/swr2/tandem.xml Mitschnitte aller Sendungen der Redaktion SWR2 Tandem sind auf CD erhältlich beim SWR Mitschnittdienst in Baden-Baden zum Preis von 12,50 Euro. Bestellungen über Telefon: 07221/929-26030 Bestellungen per E-Mail: [email protected] Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de 2 O-Ton Das war eine großartige Periode. Die beste. Da waren wir auf der Überholspur. Auch musikalisch war das eine tolle Zeit, weil da eine Menge Energie in der Luft lag. Das war eine Zeit der Experimente. Und das Ganze folgte einer großen Ära des Rock'n'Roll. Die Quellen, aus denen wir Musiker damals schöpfen konnten, waren also sehr reichhaltig. In den folgenden Jahrzehnten konnten wir nie mehr auf so ergiebige Quellen zurückgreifen. Die Musik der 70er Jahre zum Beispiel war viel flacher und nicht annähernd so anregend wie die aus den 50er Jahren. -

29649 Hamelink V5.Indd 1 21-08-14 14:28 © 2014, Wendelmoet Hamelink, Leiden, the Netherlands

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/29088 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Hamelink, Akke Wendelmoet Title: The Sung home : narrative, morality, and the Kurdish nation Issue Date: 2014-10-09 The Sung Home Narrative, morality, and the Kurdish nation Wendelmoet Hamelink 29649_Hamelink v5.indd 1 21-08-14 14:28 © 2014, Wendelmoet Hamelink, Leiden, the Netherlands. No part of this dissertation may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission of the author. Cover photo: Çüngüş, Diyarbakır province Photography by Jelle Verheij Cover design: Pieter Lenting, GVO drukkers & vormgevers B.V. | Ponsen & Looijen, Ede, the Netherlands Layout: Arthur van Aken, Leeuwenkracht - Vormgeving en DTP, Zeist, the Netherlands Ferdinand van Nispen, Citroenvlinder-DTP.nl, Bilthoven, the Netherlands Printed by: GVO drukkers & vormgevers B.V. | Ponsen & Looijen, Ede, the Netherlands The research presented in this dissertation was financially supported by the Leiden Institute of Area Studies and the Institute of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology at Leiden University, and by the LUF Leids Universiteits Fonds. I received financial support for the publication of this dissertation by the Jurriaanse Stichting, Volkskracht.nl, in Rotterdam. 29649_Hamelink v5.indd 2 21-08-14 14:28 The Sung Home Narrative, morality, and the Kurdish nation Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof.mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op donderdag 9 oktober 2014 klokke 13.45 door Akke Wendelmoet Hamelink Geboren te Ede (Gld) in 1975 29649_Hamelink v5.indd 3 21-08-14 14:28 Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof. -

Creative Industries: Behind the Scenes Inequalities

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Theses Department of Sociology Fall 12-17-2019 CREATIVE INDUSTRIES: BEHIND THE SCENES INEQUALITIES Sierra C. Nicely Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_theses Recommended Citation Nicely, Sierra C., "CREATIVE INDUSTRIES: BEHIND THE SCENES INEQUALITIES." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_theses/86 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREATIVE INDUSTRIES: BEHIND THE SCENES INEQUALITIES by SIERRA NICELY Under the Direction of Wendy Simonds, PhD ABSTRACT Film has been a major influence since its creation in the early 20th century. Women have always been involved in the creation of film as a cultural product. However, they have rarely been given positions of power in major film productions. Using qualitative approaches, I examine the different ways in which men and women directors approach creating film. I examine 20 films, half were directed by men and half by women. I selected the twenty films out of two movie genres: Action and Romantic Comedy. These genres were chosen because of their very gendered marketing. My focus was on the different ways in which gender was shown on screen and the differences in approach by men and women directors. The research showed differences in approach of gender but also different approaches in race and sexuality. Future studies should include more analysis on differences by race and sexuality. -

10 Cc 10000 Maniacs 2 Unlimited 3 Doors Down

10 CC ALL SAINTS I'm not in love 6127 I know where it's at 2797 10000 MANIACS never ever 2794 more than this 2898 ALL-4-ONE 2 UNLIMITED I swear 2888 No limit 6067 ALPHAVILLE 3 DOORS DOWN Forever young 6076 when i'm gone 2849 AMERICA 4 NON BLONDES a horse with no name 2595 What's going on 6121 Razorlight 3506 5 Seconds of Summer AMY GRANT Yougblood 4525 take a little time 2900 98 DEGREES AMY WINEHOUSE give me just one night 2825 Rehab 6402 AALIYAH ANDREAS JOHNSON are you that somebody 2925 Glorious 3508 ABBA ANDREW SISTERS dancing queen 2138 boogie woogie bugle boy 2321 does your mother know 2144 ANDY WILLIAMS fernando 2141 moon river 2562 gimme ! gimme ! gimme ! 2143 Anna Kendrick I do, i do, i do, i do, i do 2142 Cups (Pich Perfect "When I'm gone") 4412 I have dream 2145 Anne Marie knowing me, knowing you 2133 2002 4527 s.o.s 2136 Perfect to me 4528 take a chance on me 2140 AQUA thank you for the music 2137 barbie girl 2681 the winner take it all 2132 ARETHA FRANKLIN waterloo 2139 respect 2583 ABBA TRIBUTE Say a little prayer 6074 Thank ABBA for the music 3640 Ariana Grande ACDC 7 rings 4530 Highway to hell 6059 Almost Is Never Enough 4070 ACE OF BASE Bad idea 4531 living in danger 2508 Better off 4532 Adele Break Free 4071 Hello 4320 Break up with your girlfriend 4533 Hello 4200 Breathin 4534 Make you feel my love 3708 Everytime 4535 Rolling in Deep 3504 God is a woman 4536 Set the fire to the rain 3706 Imagine 4537 Someone like you 3707 Just A Little Bit Of Your Heart 4072 When we were young 4201 Love Me Harder 4073 AGNES Monopoly 4541 Release me 6401 NASA 4538 A-HA Needy 4529 take on me 2299 No tears left to cry 4539 Alan Walker Positions 4741 Faded 4203 Problem (feat. -

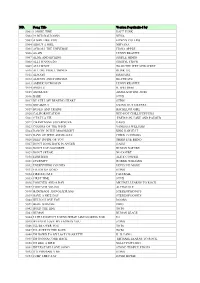

Songs by Artist

YouStarKaraoke.com Songs by Artist 602-752-0274 Title Title Title 1 Giant Leap 1975 3 Doors Down My Culture City Let Me Be Myself (Wvocal) 10 Years 1985 Let Me Go Beautiful Bowling For Soup Live For Today Through The Iris 1999 Man United Squad Loser Through The Iris (Wvocal) Lift It High (All About Belief) Road I'm On Wasteland 2 Live Crew The Road I'm On 10,000 MANIACS Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I M Gone Candy Everybody Wants Doo Wah Diddy When I'm Gone Like The Weather Me So Horny When You're Young More Than This We Want Some PUSSY When You're Young (Wvocal) These Are The Days 2 Pac 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Trouble Me California Love Landing In London 100 Proof Aged In Soul Changes 3 Doors Down Wvocal Somebody's Been Sleeping Dear Mama Every Time You Go (Wvocal) 100 Years How Do You Want It When You're Young (Wvocal) Five For Fighting Thugz Mansion 3 Doors Down 10000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Road I'm On Because The Night 2 Pac & Eminem Road I'm On, The 101 Dalmations One Day At A Time 3 LW Cruella De Vil 2 Pac & Eric Will No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 10CC Do For Love 3 Of A Kind Donna 2 Unlimited Baby Cakes Dreadlock Holiday No Limits 3 Of Hearts I'm Mandy 20 Fingers Arizona Rain I'm Not In Love Short Dick Man Christmas Shoes Rubber Bullets 21St Century Girls Love Is Enough Things We Do For Love, The 21St Century Girls 3 Oh! 3 Wall Street Shuffle 2Pac Don't Trust Me We Do For Love California Love (Original 3 Sl 10CCC Version) Take It Easy I'm Not In Love 3 Colours Red 3 Three Doors Down 112 Beautiful Day Here Without You Come See Me -

Forum Addresses Minority Concerns

CAMPUS SPORTS CAMPUS WSU curriculum tries Cougars tackle Cardinal Center offers rentals to pass the class I page 7 for Pac- 10 pride I page 13 for winter sports I page 8 November 2 1990 Establishedver1894 een Vol. 97 No. 55 Forum addresses minority concerns dants focused around recruitment minority student counselors Sneed said minorities are By Carrie Hartman mative Action employee, said and retention of minority faculty emphasized the need for WSU to found in job pools for counselors minorities are being recruited for Staff Writer members, teaching existing fac- adopt a stronger stance on the and similar positions, but not faculty positions at WSU. Lack of communication and ulty on cultural differences and minority relations issue. faculty. misinterpretation on both sides of racial sensitivity to minority stu- "There needs to be a bold step Bennie Harris, a WSU Affir- See FORUM on page 7 the racial coin is the main prob- dents, and encouraging minority taken by President Smith saying lem facing WSU students and students to attend WSU. that departments cannot hire fac- faculty, said Ron Thomas, "When we decide that a qual- ulty members unless there are Survey: discrimination found ASWSU Minority Affairs repre- ity higher education means that women and minorities in the sentative at a minority forum we must go beyond our own cul- applicant pool," said Stephen By Jennifer Jones The survey was conducted Thursday night. tural backgrounds and required Sneed, director of Minority Staff Writer for WSU President Sam About 45 concerned WSU stu- GURs to learn about other cul- Affairs. Smith's Commission on the dents, faculty representatives and tures who are not like us, then "Right now they're doing a Reverse, racial and sex dis- Status of Minorities and was members of various minority we'll start making a serious poor job at taking those kinds of crimination and stereotyping designed to paint an accurate groups met to discuss problems attempt at instilling programs," steps," he said. -

DCP (Don Costa Productions) International Label/Veep Label

DCP (Don Costa Productions) International Label/Veep Label Discography Don Costa started arranging material for Steve Lawrence and Edyie Gorme and went with them to the new record label ABC-Paramount in 1958. At ABC, Costa became head of A&R as well as chief arranger and producer. He produced hits for Lloyd Price, George Hamilton IV and Paul Anka. DCP International was started by Don Costa after leaving ABC Paramount in 1964. United Artists purchased the label in 1966 and the name was changed to Veep. 3800/6800 Series DCL 3800/DCS 6800 - When You’re Young and In Love - Kathy Keegan [1964] When You’re Young and In Love/Before The Parade Passes By/I Could Have Danced All Night/Was She Prettier Than I?/Moment of Truth/I Want To Be With You//This Is The Life/Meditation/A Different Kind of Love/My Kind of Town/I Get Along Without You Very Well/When The Wind Was Green DCL 3801/DCS 6801 - I’m on the Outside (Looking In) - Little Anthony & The Imperials [1964] I’m on the Outside (Looking In)/Where Did Our Love Go?/People/The Girl From Ipanema/Make It Easy On Yourself/Walk On By//Tears On My Pillow/Exodus/Funny/Please Go/Our Song/A Letter A Day DCL 3802/DCS 6802 - The Golden Touch - Don Costa [1964] Exodus/Put Your Head On My Shoulder/Gina/Pretty Blue Eyes/I’llTake Romance/If I Had A Hammer//(You’ve Got) Personality/When The Boys In Your Arms (Is The Boy In Your Heart)/Make Yourself Comfortable/The Magnificent Seven/Town Without Pity/Never On Sunday DCL 3805/DCS 6805 - The Monster Album - The Monster [1964] Frankenstein Meets The Beatles/Ghoul -

The Revels Repertoire

THE REVELS REPERTOIRE POP Ain’t It Fun – Paramore Don’t StoP the Music – Rihanna All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Dynamite – Taio Cruz American Boy – Estelle Everybody – Backstreet Boys Animal – Neon Trees Everybody Talks – Neon Trees Baby I Love Your Way – Big Mountain, Tom Exs and Ohs – Elle King Lord-Alge Firework – Katy Perry Back to Black – Amy Winehouse Forever – Chris Brown Bad Guy – Billie Eilish Forget You – CeeLo Green Bad Romance – Lady Gaga Feels – Calvin Harris, Pharrell Williams, Bang Bang – Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Katy Perry Minaj Feel It Coming – The Weeknd Believe – Cher Feel It Still – Portugal. The Man Best Day of My Life – American Authors Get Lucky – Daft Punk Born This Way – Lady Gaga Get the Party Started – P!nk Bye Bye Bye – *NSYNC Give Me Everything – Ne-yo and Pitbull Cake by the Ocean – DNCE Good as Hell – Lizzo California Gurls – Katy Perry HaPPy – Pharrel Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae JePsen Havana – Camila Cabello Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Heaven – Los Lonely Boys Can’t StoP the Feeling – Justin Timberlake Hey Soul Sister – Train Candyman – Christina Aguilera High Horse – Kacey Musgraves Chandelier – Sia Ho Hey – The Lumineers CheaP Thrills – Sia Hold My Hand – Jess Glynne Cheerleader – OMI Holiday – Madonna Closer – The Chainsmokers I Don’t Like It, I Love It – Flo Rida and Robin Counting Stars – OneRePublic Thicke Crazy – Gnarls Barkley I Kissed a Girl – Katy Perry CreeP – TLC I Love It – Icona PoP Cruel Summer – Bananarama I Love You Always Forever – Donna Lewis Dancing on My Own – Robyn Into You – Ariana Grande Dear Future Husband – Meghan Trainor I Will Wait – Mumford & Sons Déjà Vu – Beyonce Ice Ice Baby – Vanilla Ice Domino – Jessie J Juice – Lizzo 1 Just Dance – Lady Gaga ShaPe of You – Ed Sheeran Just Fine – Mary J. -

POP Vol 1 Song List

NO. Song Title Version Popularized by 5001 1 MORE TIME DAFT FUNK 5002 99 RED BALLOONS NENA 5003 A GIRL LIKE YOU EDWYN COLLINS 5004 ABOUT A GIRL NIRVANA 5005 ACROSS THE UNIVERSE FIONA APPLE 5006 AGAIN LENNY KRAVITZ 5007 ALIVE AND KICKING SIMPLE MINDS 5008 ALL I WANNA DO SHERYL CROW 5009 ALL I WANT TOAD THE WET SPROCKET 5010 ALL THE SMALL THINGS BLINK 182 5011 ALWAYS ERASURE 5012 ALWAYS AND FOREVER HEATWAVE 5013 AMERICAN WOMAN LENNY KRAVITZ 5014 ANGELS R. WILLIMAS 5015 ANTMUSIC ADAM AND THE ANTS 5016 BABE STYX 5017 BE STILL MY BEATING HEART STING 5018 BREAKOUT SWING OUT SISTERS 5019 BUSES AND TRAINS BACHELOR GIRL 5020 CALIFORNICATION RED HOT CHILLI PEPPERS 5021 C’EST LA VIE EMERSON, LAKE AND PALMER 5022 CHAMPAGNE SUPERNOVA OASIS 5023 COLORS OF THE WIND VANESSA WILLIAMS 5024 DANCIN’ IN THE MOONLIGHT KING HARVEST 5025 DAYS OF WINE AND ROSES CHRIS CONNORS 5026 DEEP INSIDE OF YOU THIRD EYE BLIND 5027 DON’T LOOK BACK IN ANGER OASIS 5028 DON’T SAY GOODBYE HUMAN NATURE 5029 DON’T SPEAK NO DOUBT 5030 EIGHTEEN ALICE COOPER 5031 ETERNITY ROBBIE WILLIAMS 5032 EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE 5033 FIELDS OF GOLD STING 5034 FIRE ESCAPE FASTBALL 5035 FIRST TIME STYX 5036 FOREVER AND A DAY MICHAEL LEARNS TO ROCK 5037 FOREVER YOUNG ALPHAVILLE 5038 HANDBAGS AND GLADRAGS STEREOPHONICS 5039 HAVE A NICE DAY STEREOPHONICS 5040 HELLO I LOVE YOU DOORS 5041 HERE WITH ME DIDO 5042 HOLD THE LINE TOTO 5043 HUMAN HUMAN LEAGE 5044 I STILL HAVEN’T FOUND WHAT I AM LOOKING FOR U2 5045 IF I EVER LOSE MY FAITH IN YOU STING 5046 I’LL BE OVER YOU TOTO 5047 I’LL SUPPLY THE LOVE TOTO 5048 I’M DOWN TO MY LAST CIGARETTE K.