The ILLIAC IV Computer 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Stored Program Computers

Stored Program Computers Thomas J. Bergin Computing History Museum American University 7/9/2012 1 Early Thoughts about Stored Programming • January 1944 Moore School team thinks of better ways to do things; leverages delay line memories from War research • September 1944 John von Neumann visits project – Goldstine’s meeting at Aberdeen Train Station • October 1944 Army extends the ENIAC contract research on EDVAC stored-program concept • Spring 1945 ENIAC working well • June 1945 First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC 7/9/2012 2 First Draft Report (June 1945) • John von Neumann prepares (?) a report on the EDVAC which identifies how the machine could be programmed (unfinished very rough draft) – academic: publish for the good of science – engineers: patents, patents, patents • von Neumann never repudiates the myth that he wrote it; most members of the ENIAC team contribute ideas; Goldstine note about “bashing” summer7/9/2012 letters together 3 • 1.0 Definitions – The considerations which follow deal with the structure of a very high speed automatic digital computing system, and in particular with its logical control…. – The instructions which govern this operation must be given to the device in absolutely exhaustive detail. They include all numerical information which is required to solve the problem…. – Once these instructions are given to the device, it must be be able to carry them out completely and without any need for further intelligent human intervention…. • 2.0 Main Subdivision of the System – First: since the device is a computor, it will have to perform the elementary operations of arithmetics…. – Second: the logical control of the device is the proper sequencing of its operations (by…a control organ. -

Computer Development at the National Bureau of Standards

Computer Development at the National Bureau of Standards The first fully operational stored-program electronic individual computations could be performed at elec- computer in the United States was built at the National tronic speed, but the instructions (the program) that Bureau of Standards. The Standards Electronic drove these computations could not be modified and Automatic Computer (SEAC) [1] (Fig. 1.) began useful sequenced at the same electronic speed as the computa- computation in May 1950. The stored program was held tions. Other early computers in academia, government, in the machine’s internal memory where the machine and industry, such as Edvac, Ordvac, Illiac I, the Von itself could modify it for successive stages of a compu- Neumann IAS computer, and the IBM 701, would not tation. This made a dramatic increase in the power of begin productive operation until 1952. programming. In 1947, the U.S. Bureau of the Census, in coopera- Although originally intended as an “interim” com- tion with the Departments of the Army and Air Force, puter, SEAC had a productive life of 14 years, with a decided to contract with Eckert and Mauchly, who had profound effect on all U.S. Government computing, the developed the ENIAC, to create a computer that extension of the use of computers into previously would have an internally stored program which unknown applications, and the further development of could be run at electronic speeds. Because of a demon- computing machines in industry and academia. strated competence in designing electronic components, In earlier developments, the possibility of doing the National Bureau of Standards was asked to be electronic computation had been demonstrated by technical monitor of the contract that was issued, Atanasoff at Iowa State University in 1937. -

Performing the Shuffle with the PM2I and Illiac SIMD Interconnection Networks

Performing the Shuffle with the PM2I and Illiac SIMD Interconnection Networks Robert R. Seban Howard Jay Siegel Purdue University School of Electrical Engineering West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 Abstract—Three SIMD single stage interconnection networks which have been proposed and studied in the literature are the Illiac, PM2I, and Shuffle-Exchange. Here the ability of the Illiac and PM2I networks to per- form the shuffle interconnection in an SIMD machine with N processors is examined. A lower bound of 3\/N/2 transfers for the Illiac to shuffle data is derived. An algorithm to do this task in 2\/N-l transfers is given. A lower bound of log2N transfers for the PM2I to shuffle data has been published previously. An algo- rithm to do this task in log2N + l in transfers is presented here. 1. Introduction This paper extends SIMD interconnection network studies presented in [28, 31]. In particular, the ability of Fig. 1: PE-to-PE SIMD machine configuration, with the PM2I and Illiac single stage interconnection SIMD machine networks to perform the shuffle interconnection NPEs. is examined. In [28] it is shown that a lower bound on of configuration is shown in Fig. 1. It is called the PE- the number of transfers needed for the PM2I network to to-PE organization. The network is unidirectional and perform the shuffle is log2N, where N is the number of connects each PE to some subset of the other PEs. A processing elements in the SIMD machine. The algo- transfer instruction causes data to be moved from each rithm presented here requires only (log2N) + l transfers. -

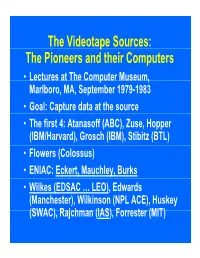

P the Pioneers and Their Computers

The Videotape Sources: The Pioneers and their Computers • Lectures at The Compp,uter Museum, Marlboro, MA, September 1979-1983 • Goal: Capture data at the source • The first 4: Atanasoff (ABC), Zuse, Hopper (IBM/Harvard), Grosch (IBM), Stibitz (BTL) • Flowers (Colossus) • ENIAC: Eckert, Mauchley, Burks • Wilkes (EDSAC … LEO), Edwards (Manchester), Wilkinson (NPL ACE), Huskey (SWAC), Rajchman (IAS), Forrester (MIT) What did it feel like then? • What were th e comput ers? • Why did their inventors build them? • What materials (technology) did they build from? • What were their speed and memory size specs? • How did they work? • How were they used or programmed? • What were they used for? • What did each contribute to future computing? • What were the by-products? and alumni/ae? The “classic” five boxes of a stored ppgrogram dig ital comp uter Memory M Central Input Output Control I O CC Central Arithmetic CA How was programming done before programming languages and O/Ss? • ENIAC was programmed by routing control pulse cables f ormi ng th e “ program count er” • Clippinger and von Neumann made “function codes” for the tables of ENIAC • Kilburn at Manchester ran the first 17 word program • Wilkes, Wheeler, and Gill wrote the first book on programmiidbBbbIiSiing, reprinted by Babbage Institute Series • Parallel versus Serial • Pre-programming languages and operating systems • Big idea: compatibility for program investment – EDSAC was transferred to Leo – The IAS Computers built at Universities Time Line of First Computers Year 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 ••••• BTL ---------o o o o Zuse ----------------o Atanasoff ------------------o IBM ASCC,SSEC ------------o-----------o >CPC ENIAC ?--------------o EDVAC s------------------o UNIVAC I IAS --?s------------o Colossus -------?---?----o Manchester ?--------o ?>Ferranti EDSAC ?-----------o ?>Leo ACE ?--------------o ?>DEUCE Whirl wi nd SEAC & SWAC ENIAC Project Time Line & Descendants IBM 701, Philco S2000, ERA.. -

Online Sec 6.15.Indd

6.155.9 Historical Perspective and Further Reading Th ere is a tremendous amount of history in multiprocessors; in this section we divide our discussion by both time period and architecture. We start with the SIMD approach and the Illiac IV. We then turn to a short discussion of some other early experimental multiprocessors and progress to a discussion of some of the great debates in parallel processing. Next we discuss the historical roots of the present multiprocessors and conclude by discussing recent advances. SIMD Computers: Attractive Idea, Many Attempts, No Lasting Successes Th e cost of a general multiprocessor is, however, very high and further design options were considered which would decrease the cost without seriously degrading the power or effi ciency of the system. Th e options consist of recentralizing one of the three major components. Centralizing the [control unit] gives rise to the basic organization of [an] . array processor such as the Illiac IV. Bouknight et al. [1972] Th e SIMD model was one of the earliest models of parallel computing, dating back to the fi rst large-scale multiprocessor, the Illiac IV. Th e key idea in that multiprocessor, as in more recent SIMD multiprocessors, is to have a single instruction that operates on many data items at once, using many functional units (see Figure 6.15.1). Although successful in pushing several technologies that proved useful in later projects, it failed as a computer. Costs escalated from the $8 million estimate in 1966 to $31 million by 1972, despite construction of only a quarter of the planned multiprocessor. -

SIMD1 Ñ Illiac IV

Illiac IV History Illiac IV n First massively parallel computer ● SIMD (duplicate the PE, not the CU) ● First large system with semiconductor- based primary memory n Three earlier designs (vacuum tubes and transistors) culminating in the Illiac IV design, all at the University of Illinois ● Logical organization similar to the Solomon (prototyped by Westinghouse) ● Sponsored by DARPA, built by various companies, assembled by Burroughs ● Plan was for 256 PEs, in 4 quadrants of 64 PEs, but only one quadrant was built ● Used at NASA Ames Research Center in mid-1970s 1 Fall 2001, Lecture SIMD1 2 Fall 2001, Lecture SIMD1 Illiac IV Architectural Overview Programming Issues n One CU (control unit), n Consider the following FORTRAN code: 64 64-bit PEs (processing elements), DO 10 I = 1, 64 each PE has a PEM (PE memory) 10 A(I) = B(I) + C(I) ● Put A(1), B(1), C(1) on PU 1, etc. n CU operates on scalars, PEs on vector- n Each PE loads RGA from base+1, aligned arrays adds base+2, stores into base, ● All PEs execute the instruction broadcast where “base” is base of data in PEM by the CU, if they are in active mode n Each PE does this simultaneously, giving a speedup of 64 ● Each PE can perform various arithmetic ● and logical instructions For less than 64 array elements, some processors will sit idle ● Each PE has a memory with 2048 64-bit ● words, accessed in less than 188 ns For more than 64 array elements, some processors might have to do more work ● PEs can operate on data in 64-bit, 32-bit, and 8-bit formats n For some algorithms, it may be desirable to turn off PEs n Data routed between PEs various ways ● 64 PEs compute, then one half passes data to other half, then 32 PEs compute, n I/O is handled by a separate Burroughs etc. -

Oral History Interview with David J. Wheeler

An Interview with DAVID J. WHEELER OH 132 Conducted by William Aspray on 14 May 1987 Princeton, NJ Charles Babbage Institute The Center for the History of Information Processing University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Copyright, Charles Babbage Institute 1 David J. Wheeler Interview 14 May 1987 Abstract Wheeler, who was a research student at the University Mathematical Laboratory at Cambridge from 1948-51, begins with a discussion of the EDSAC project during his tenure. He compares the research orientation and the programming methods at Cambridge with those at the Institute for Advanced Study. He points out that, while the Cambridge group was motivated to process many smaller projects from the larger university community, the Institute was involved with a smaller number of larger projects. Wheeler mentions some of the projects that were run on the EDSAC, the user-oriented programming methods that developed at the laboratory, and the influence of the EDSAC model on the ILLIAC, the ORDVAC, and the IBM 701. He also discusses the weekly meetings held in conjunction with the National Physical Laboratory, the University of Birmingham, and the Telecommunications Research Establishment. These were attended by visitors from other British institutions as well as from the continent and the United States. Wheeler notes visits by Douglas Hartree (of Cavendish Laboratory), Nelson Blackman (of ONR), Peter Naur, Aad van Wijngarden, Arthur van der Poel, Friedrich L. Bauer, and Louis Couffignal. In the final part of the interview Wheeler discusses his visit to Illinois where he worked on the ILLIAC and taught from September 1951 to September 1953. 2 DAVID J. -

Vector Machines Vector Machines Today Introduction a Vector Processor Is a CPU That Can Run One Instructiononanentire Vector of Data

Hakam Zaidan Stephen Moore Outline Vector Architectures Properties Applications History Westinghouse Solomon ILLIAC IV CDC STAR 100 Cray‐1 Other Cray Vector Machines Vector Machines Today Introduction A Vector processor is a CPU that can run one instructiononanentire vector of data. The fetched number of instructions are small. They also achieve data parallelism in large scientific and multimedia applications. Styles of Vector Architectures Based on how the operands are fetched, vector processors can be divided into two categories: Memory‐Memory Architecture. Vector‐Register Architecture. Vector Processor Elements Vector Register: Fixed length, single vector, ports for reading and writing. Usually 8 to 32 registers of length 64 or 128 bits. Vector Functional Units (FUs): Usually 4‐8 functional units: FP mult, FP add, and FP divide, in addition to the integer add and logical shift Vector Load Store Unit (LSUs). Scalar registers. Cross‐bar. Vector Processor Properties Results are independent. Known pattern for memory access by the vector instructions. In pipelines, branches and branch problems are reduced. Single vector instruction indicate huge amount of calculations (e.g. loops). Disadvantages With scalar instructions: Relatively slow. Some difficulties in the implementation of the precise exceptions. High cost for on‐chip vector memory systems. Code complexity. Applications Lossy compression. Lossless compression. Multimedia Processing. Standard benchmarking kernels. Handwriting recognition. Speech recognition. Cryptography. Operating system and networking. Databases. Support of language run‐time. History In 1962, Illinois Automatic Computer series of super computers ILLIAC I, ILLIAC II, ILLIAC III, ILLIAC IV (with 64 ALUs 100‐ 150 Mflops). In 1973 TI’s Advance Scientific Computer (ASC) 20‐80 Mflops. -

Markov Chain Monte Carlo Methods

Introduction to Machine Learning CMU-10701 Markov Chain Monte Carlo Methods Barnabás Póczos Contents Markov Chain Monte Carlo Methods Sampling • Rejection • Importance • Hastings-Metropolis • Gibbs Markov Chains • Properties Particle Filtering • Condensation 2 Monte Carlo Methods 3 Markov Chain Monte Carlo History A recent survey places the Metropolis algorithm among the 10 algorithms that have had the greatest influence on the development and practice of science and engineering in the 20th century (Beichl&Sullivan, 2000). The Metropolis algorithm is an instance of a large class of sampling algorithms, known as Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) MCMC plays significant role in statistics, econometrics, physics and computing science. There are several high-dimensional problems, such as computing the volume of a convex body in d dimensions and other high-dim integrals, for which MCMC simulation is the only known general approach for providing a solution within a reasonable time. 4 Markov Chain Monte Carlo History While convalescing from an illness in 1946, Stanislaw Ulam was playing solitaire. It, then, occurred to him to try to compute the chances that a particular solitaire laid out with 52 cards would come out successfully (Eckhard, 1987). Exhaustive combinatorial calculations are very difficult. New, more practical approach: laying out several solitaires at random and then observing and counting the number of successful plays. This idea of selecting a statistical sample to approximate a hard combinatorial problem by a much simpler problem is at the heart of modern Monte Carlo simulation. 5 FERMIAC FERMIAC: The beginning of Monte Carlo Methods Developed in the Early 1930’s The Monte Carlo trolley, or FERMIAC, was an analog computer invented by physicist Enrico Fermi to aid in his studies of neutron transport. -

Parallel Architecture Hardware and General Purpose Operating System

Parallel Architecture Hardware and General Purpose Operating System Co-design Oskar Schirmer G¨ottingen, 2018-07-10 Abstract Because most optimisations to achieve higher computational performance eventually are limited, parallelism that scales is required. Parallelised hard- ware alone is not sufficient, but software that matches the architecture is required to gain best performance. For decades now, hardware design has been guided by the basic design of existing software, to avoid the higher cost to redesign the latter. In doing so, however, quite a variety of supe- rior concepts is excluded a priori. Consequently, co-design of both hardware and software is crucial where highest performance is the goal. For special purpose application, this co-design is common practice. For general purpose application, however, a precondition for usability of a computer system is an arXiv:1807.03546v1 [cs.DC] 10 Jul 2018 operating system which is both comprehensive and dynamic. As no such op- erating system has ever been designed, a sketch for a comprehensive dynamic operating system is presented, based on a straightforward hardware architec- ture to demonstrate how design decisions regarding software and hardware do coexist and harmonise. 1 Contents 1 Origin 4 1.1 Performance............................ 4 1.2 Limits ............................... 5 1.3 TransparentStructuralOptimisation . 8 1.4 VectorProcessing......................... 9 1.5 Asymmetric Multiprocessing . 10 1.6 SymmetricMulticore ....................... 11 1.7 MultinodeComputer ....................... 12 2 Review 14 2.1 SharedMemory.......................... 14 2.2 Cache ............................... 15 2.3 Synchronisation .......................... 15 2.4 Time-Shared Multitasking . 15 2.5 Interrupts ............................. 16 2.6 Exceptions............................. 16 2.7 PrivilegedMode.......................... 17 2.8 PeripheralI/O ......................... -

The CRAY- 1 Computer System

We believe the key to the 10's longevity is its basically simple, clean structure with adequately large (one Mbyte) address space that allows users to get work done. In this way, it has evolved easily with use and with technology. An equally significant factor in Computer G. Bell, S. H. Fuller, and its success is a single operating system environment Systems D. Siewiorek, Editors enabling user program sharing among all machines. The machine has thus attracted users who have built significant languages and applications in a variety of The CRAY- 1 environments. These user-developers are thus the dominant system architects-implementors. Computer System In retrospect, the machine turned out to be larger Richard M. Russell and further from a minicomputer than we expected. Cray Research, Inc. As such it could easily have died or destroyed the tiny DEC organization that started it. We hope that this paper has provided insight into the interactions of its development. This paper describes the CRAY,1, discusses the evolution of its architecture, and gives an account of Acknowledgments. Dan Siewiorek deserves our some of the problems that were overcome during its greatest thanks for helping with a complete editing of manufacture. the text. The referees and editors have been especially The CRAY-1 is the only computer to have been helpful. The important program contributions by users built to date that satisfies ERDA's Class VI are too numerous for us to give by name but here are requirement (a computer capable of processing from most of them: APL, Basic, BLISS, DDT, LISP, Pascal, 20 to 60 million floating point operations per second) Simula, sos, TECO, and Tenex. -

11/15/20 Engineering Computer Science James E. Robertson

The materials listed in this document are available for research at the University of Record Series Number Illinois Archives. For more information, email [email protected] or search http://www.library.illinois.edu/archives/archon for the record series number. 11/15/20 Engineering Computer Science James E. Robertson Papers, 1942-93 TABLE OF CONTENTS Material Box Biographical 1 Publications 1 Correspondence 1-3 Photography 3 Subject Files 1942-62 3 1962-65 4 1965-72 5 1972-88 6-7 1948-53 11 1953-58 12 1958-70 13 Course Material 8-9, 13 Research Papers, Publications, and Reports 9-10, 13 Computer Logbooks and Manuals 14-15 Computer Codes 16 Oversize 10, 16 11/15/20 2 Box 1: BIOGRAPHICAL Biographical and vitas, ca. 1950s, 1966, 1981, 1993 Appointments, 1949-72 PUBLICATIONS 1952-59 1960-67 1973-79 1980-83 1985-87 CORRESPONDENCE 1947, 1949 (4 folders), 1950-54 (4 folders), 1955-56 (2 folders), 1957-58 (18 folders), 1959-74 Box 2: Correspondence (9 folders), 1975-79 DCL Correspondence (13 folders), 1980-82 Box 3: DCL Correspondence (7 folders), 1983-July 1984 Correspondence (2 folders), 1985-90 PHOTOGRAPHY, J.E. ROBERTSON Drum Photos, Sept. 1953 Old Photos (Ordvac and Illiac), 1954 Pacific Travel Photo listing, 1962-63 Computer Panels & U of I photos, ca. 1965-70 Arithmetic Unit Glass Slides Fast Switching Experiment Glass Slides SUBJECT FILE, 1942-62 Certificates, 1942-51 Burks, Goldstine & von Neumann, Logical Design of an Electronic Computer 1946-47 Computer Memory Improvement article in C-U Gazette, Feb. 8, 1949 "Preliminary Design of an Arithmetic Unit for...Binary Digital Computer," by J.E.R., June 23, 1950 Ordvac article in Daily Oklahoman, Jan.