Section 4: U.S.-China Clean Energy Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

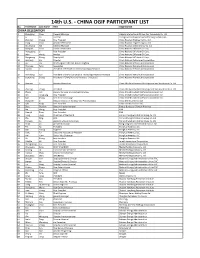

14TH OGIF Participant List.Xlsx

14th U.S. ‐ CHINA OGIF PARTICIPANT LIST No. First Name Last Name Title Organization CHINA DELEGATION 1 Zhangxing Chen General Manager Calgary International Oil and Gas Technology Co. Ltd 2 Li He Director Cheng Du Development and Reforming Commission 3 Zhaohui Cheng Vice President China Huadian Engineering Co. Ltd 4 Yong Zhao Assistant President China Huadian Engineering Co. Ltd 5 Chunwang Xie General Manager China Huadian Green Energy Co. Ltd 6 Xiaojuan Chen Liason Coordinator China National Offshore Oil Corp. 7 Rongguang Li Vice President China National Offshore Oil Corp. 8 Wen Wang Analyst China National Offshore Oil Corp. 9 Rongwang Zhang Deputy GM China National Offshore Oil Corp. 10 Weijiang Liu Director China National Petroleum Cooperation 11 Bo Cai Chief Engineer of CNPC RIPED‐Langfang China National Petroleum Corporation 12 Chenyue Feng researcher China National Petroleum Corporation 13 Shaolin Li President of PetroChina International (America) Inc. China National Petroleum Corporation 14 Xiansheng Sun President of CNPC Economics & Technology Research Institute China National Petroleum Corporation 15 Guozheng Zhang President of CNPC Research Institute(Houston) China National Petroleum Corporation 16 Xiaquan Li Assistant President China Shenhua Overseas Development and Investment Co. Ltd 17 Zhiming Zhang President China Shenhua Overseas Development and Investment Co. Ltd 18 Zhang Jian deputy manager of unconventional gas China United Coalbed Methane Corporation Ltd 19 Wu Jianguang Vice President China United Coalbed Methane Corporation Ltd 20 Jian Zhang Vice General Manager China United Coalbed Methane Corporation Ltd 21 Dongmei Li Deputy Director of Strategy and Planning Dept. China Zhenhua Oil Co. Ltd 22 Qifa Kang Vice President China Zhenhua Oil Co. -

The Next Wave of Chinese Lng Importers

THE NEXT WAVE OF CHINESE LNG IMPORTERS Jenny Yang Xizhou Zhou (Presenter) Director, IHS Markit Greater China Power, Gas, Coal, and Renewables Managing Director, IHS Markit Many new and potential LNG importers have emerged in China, thanks to a combination of policy support and market fundamentals. Together, these new players present an important new source of LNG demand in the global market and significant opportunities for suppliers. However, further reforms are needed to transform the current market structure and remove obstacles for these new players. What are the challenges facing new LNG importers? What is being done to release their full potential? How will international suppliers get familiar with them? Jenny Yang, IHS Markit Key implications1 Chinese government policies allowing more players in wholesale natural gas supply had and will continue to affect the global LNG market. The country’s three national oil companies (NOCs) have traditionally monopolized China’s gas importing business, but this has changed. The Chinese non-NOCs have been increasingly active in LNG importing activities. Several non-NOCs have procured new LNG supply agreements and successfully imported cargoes. Many more companies are building or proposing new LNG receiving terminals. Together, China’s non-NOCs will provide significant opportunities for suppliers. These companies vary from large end-users and citygas distributors seeking to minimize their gas procurement costs to energy companies looking for new market opportunities. However, China will need to carry out further reforms to remove obstacles for these new players. Allowing midstream access, removing barriers to downstream gas market, and reducing pricing regulations are critical steps toward realizing the full potential of China’s domestic natural gas industry. -

Nuclear Power: "Made in China"

Nuclear Power: “Made in China” Andrew C. Kadak, Ph.D. Professor of the Practice Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology Introduction There is no doubt that China has become a world economic power. Its low wages, high production capability, and constantly improving quality of goods place it among the world’s fastest growing economies. In the United States, it is hard to find a product not “Made in China.” In order to support such dramatic growth in production, China requires an enormous amount of energy, not only to fuel its factories but also to provide electricity and energy for its huge population. At the moment, on a per capita basis, China’s electricity consumption is still only 946 kilowatt-hours (kwhrs) per year, compared to 9,000 kwhrs per year for the developed world and 13,000 kwhrs per year for the United States.1 However, China’s recent electricity growth rate was estimated to be 15 percent per year, with a long-term growth rate of about 4.3 percent for the next 15 years.2 This is almost triple the estimates for most Western economies. China has embarked upon an ambitious program of expansion of its electricity sector, largely due to the move towards the new socialist market economy. As part of China’s 10th Five-Year Plan (2001-2005), a key part of energy policy is to “guarantee energy security, optimize energy mix, improve energy efficiency, protect ecological environment . .”3 China’s new leaders are also increasingly concerned about the environmental impact of its present infrastructure. -

Section 2: Emerging Technologies and Military-Civil Fusion: Artificial Intelli

SECTION 2: EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES AND MILITARY-CIVIL FUSION: ARTIFICIAL INTELLI- GENCE, NEW MATERIALS, AND NEW ENERGY Key Findings • China’s government has implemented a whole-of-society strat- egy to attain leadership in artificial intelligence (AI), new and advanced materials, and new energy technologies (e.g., energy storage and nuclear power). It is prioritizing these areas be- cause they underpin advances in many other technologies and could lead to substantial scientific breakthroughs, economic dis- ruption, enduring economic benefits, and rapid changes in mili- tary capabilities and tactics. • The Chinese government’s military-civil fusion policy aims to spur innovation and economic growth through an array of pol- icies and other government-supported mechanisms, including venture capital (VC) funds, while leveraging the fruits of civil- ian innovation for China’s defense sector. The breadth and opac- ity of military-civil fusion increase the chances civilian academ- ic collaboration and business partnerships between the United States and China could aid China’s military development. • China’s robust manufacturing base and government support for translating research breakthroughs into applications allow it to commercialize new technologies more quickly than the Unit- ed States and at a fraction of the cost. These advantages may enable China to outpace the United States in commercializing discoveries initially made in U.S. labs and funded by U.S. insti- tutions for both mass market and military use. • Artificial intelligence: Chinese firms and research institutes are advancing uses of AI that could undermine U.S. economic lead- ership and provide an asymmetrical advantage in warfare. Chi- nese military strategists see AI as a breakout technology that could enable China to rapidly modernize its military, surpassing overall U.S. -

Clean Tech Handbook for Asia Pacific May 2010

Clean Tech Handbook for Asia Pacific May 2010 Asia Pacific Clean Tech Handbook 26-Apr-10 Table of Contents FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................. 16 1 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................... 19 1.1 WHAT IS CLEAN TECHNOLOGY? ........................................................................................................................ 19 1.2 WHY CLEAN TECHNOLOGY IN ASIA PACIFIC? .......................................................................................................19 1.3 FACTORS DRIVING THE CLEAN TECH MARKET IN ASIA PACIFIC .................................................................................20 1.4 KEY CHALLENGES FOR THE CLEAN TECH MARKET IN ASIA PACIFIC ............................................................................20 1.5 WHO WOULD BE INTERESTED IN THIS REPORT? ....................................................................................................21 1.6 STRUCTURE OF THE HANDBOOK ........................................................................................................................ 21 PART A – COUNTRY REVIEW.......................................................................................................................... 22 2 COUNTRY OVERVIEW.......................................................................................................................... -

2016 State Utility Commissioners Clean Energy Policy and Technology Leadership Mission to China

2016 STATE UTILITY COMMISSIONERS CLEAN ENERGY POLICY AND TECHNOLOGY LEADERSHIP MISSION TO CHINA SPONSORED BY OFFICE OF CLEAN COAL & CARBON MANAGEMENT US-CHINA CLEAN ENERGY RESEARCH CENTER US DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY BEIJING, HAIYANG, SHANGHAI, AND ORDOS TRIP REPORT ROBERT W. GEE, PRESIDENT SHERI S. GIVENS, SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT .... Gee Strategies 11111 Group,LLc WASHINGTON | AUSTIN WITH SPECIAL APPRECIATION TO: COMMISSIONER TRAVIS KAVULLA, MONTANA COMMISSIONER DAVID ZIEGNER, INDIANA COMMISSIONER LIBBY JACOBS, IOWA COMMISSIONER SANDY JONES, NEW MEXICO COMMISSIONER SHERINA MAYE EDWARDS, ILLINIOIS JOE GIOVE, US DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY a1J1 6e e Strategies Group,LLc 11111 December 1, 2016 Dr. Robert C. Marlay US Director US-China Clean Energy Research Center Office of International Affairs US Department of Energy Mr. David Mohler Deputy Assistant Secretary for Clean Coal and Carbon Management Office of Fossil Energy US Department of Energy Dear Dr. Marlay and Mr. Mohler: We are forwarding you the 2016 Trip Report for the State Utility Commissioners Clean Energy Policy and Technology Leadership Mission to China As the attached report outlines, each goal we set out to accomplish at the outset of the mission was achieved, and we believe that the lessons learned by the participating state utility commissioners will yield dividends to the US Government and Department of Energy. We extend my deep gratitude for your support for this mission. Sincerely, Robert W. Gee President Gee Strategies Group LLC Sheri S. Givens Sheri S. Givens Senior Vice President Gee Strategies Group LLC Attachment TABLE OF CONTENTS Background 1 Delegation Meetings 2 Beijing 3 Haiyang 33 Shanghai 38 Ordos 44 Major Mission Accomplishments 56 Recommendations 58 Appendices A. -

China's Fissile Material Production and Stockpile

China’s Fissile Material Production and Stockpile Hui Zhang Research Report No. 17 International Panel on Fissile Materials China’s Fissile Material Production and Stockpile Hui Zhang 2017 International Panel on Fissile Materials This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution – Noncommercial License To view a copy of this license, visit www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 On the cover: The map shows fissile material production sites in China. Table of Contents About IPFM 1 Overview 2 Introduction 4 HEU production and inventory 7 Plutonium production and inventory 20 Summary 36 About the author 37 Endnotes 38 About the IPFM The International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM) was founded in January 2006. It is an independent group of arms-control and nonproliferation experts from seventeen countries, including both nuclear weapon and non-nuclear weapon states. The mission of the IPFM is to analyze the technical bases for practical and achievable policy initiatives to secure, consolidate, and reduce stockpiles of highly enriched urani- um and plutonium. These fissile materials are the key ingredients in nuclear weapons, and their control is critical to nuclear disarmament, halting the proliferation of nuclear weapons, and ensuring that terrorists do not acquire nuclear weapons. Both military and civilian stocks of fissile materials have to be addressed. The nuclear weapon states still have enough fissile materials in their weapon and naval fuel stock- piles for tens of thousands of nuclear weapons. On the civilian side, enough plutonium has been separated to make a similarly large number of weapons. Highly enriched ura- nium fuel is used in about one hundred research reactors. -

Charles Zhang

In a little over 35 years China’s economy has been transformed Week in China from an inefficient backwater to the second largest in the world. If you want to understand how that happened, you need to understand the people who helped reshape the Chinese business landscape. china’s tycoons China’s Tycoons is a book about highly successful Chinese profiles of entrepreneurs. In 150 easy-to- digest profiles, we tell their stories: where they came from, how they started, the big break that earned them their first millions, and why they came to dominate their industries and make billions. These are tales of entrepreneurship, risk-taking and hard work that differ greatly from anything you’ll top business have read before. 150 leaders fourth Edition Week in China “THIS IS STILL THE ASIAN CENTURY AND CHINA IS STILL THE KEY PLAYER.” Peter Wong – Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive, Asia-Pacific, HSBC Does your bank really understand China Growth? With over 150 years of on-the-ground experience, HSBC has the depth of knowledge and expertise to help your business realise the opportunity. Tap into China’s potential at www.hsbc.com/rmb Issued by HSBC Holdings plc. Cyan 611469_6006571 HSBC 280.00 x 170.00 mm Magenta Yellow HSBC RMB Press Ads 280.00 x 170.00 mm Black xpath_unresolved Tom Fryer 16/06/2016 18:41 [email protected] ${Market} ${Revision Number} 0 Title Page.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 6:36 pm Page 1 china’s tycoons profiles of 150top business leaders fourth Edition Week in China 0 Welcome Note.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 3:10 pm Page 2 Week in China China’s Tycoons Foreword By Stuart Gulliver, Group Chief Executive, HSBC Holdings alking around the streets of Chengdu on a balmy evening in the mid-1980s, it quickly became apparent that the people of this city had an energy and drive Wthat jarred with the West’s perception of work and life in China. -

GIIGNL Annual Report Profile

The LNG industry GIIGNL Annual Report Profile Acknowledgements Profile We wish to thank all member companies for their contribution to the report and the GIIGNL is a non-profit organisation whose objective following international experts for their is to promote the development of activities related to comments and suggestions: LNG: purchasing, importing, processing, transportation, • Cybele Henriquez – Cheniere Energy handling, regasification and its various uses. • Najla Jamoussi – Cheniere Energy • Callum Bennett – Clarksons The Group constitutes a forum for exchange of • Laurent Hamou – Elengy information and experience among its 88 members in • Jacques Rottenberg – Elengy order to enhance the safety, reliability, efficiency and • María Ángeles de Vicente – Enagás sustainability of LNG import activities and in particular • Paul-Emmanuel Decroës – Engie the operation of LNG import terminals. • Oliver Simpson – Excelerate Energy • Andy Flower – Flower LNG • Magnus Koren – Höegh LNG • Mariana Ortiz – Naturgy Energy Group • Birthe van Vliet – Shell • Mika Iseki – Tokyo Gas • Yohei Hukins – Tokyo Gas • Donna DeWick – Total • Emmanuelle Viton – Total • Xinyi Zhang – Total © GIIGNL - International Group of Liquefied Natural Gas Importers All data and maps provided in this publication are for information purposes and shall be treated as indicative only. Under no circumstances shall they be regarded as data or maps intended for commercial use. Reproduction of the contents of this publication in any manner whatsoever is prohibited without prior -

Nuclear Power in East Asia

4 A new normal? The changing future of nuclear energy in China M . V . Ramana and Amy King Abstract In recent years, China has reduced its goal for expanding nuclear power capacity, from a target of 70 gigawatts (GW) by 2020 issued in 2009 to just 58 GW by 2020 issued in 2016 . This chapter argues that this decline in targets stems from three key factors. The first factor is China’s transition to a relatively low-growth economy, which has led to correspondingly lower levels of growth in demand for energy and electricity . Given China’s new low- growth economic environment, we argue that the need for rapid increases in nuclear power targets will likely become a thing of the past . The second factor is the set of policy changes adopted by the Chinese government following the March 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan . Since the Fukushima disaster, China’s State Council has stopped plans for constructing inland nuclear reactors and restricted reactor construction to modern (third-generation) designs . The third factor is government responsiveness to public opposition to the siting of nuclear facilities near population centres . Collectively, these factors are likely to lead to a decline in the growth rate of nuclear power in China . 103 LEARNING FROM FUKUSHIMA Introduction In March 2016, China’s National People’s Congress endorsed its draft 13th Five Year Plan (2016–20), which set China the goal of developing 58 gigawatts (GW) of operating nuclear capacity by 2020, with another 30 GW to be under construction by then. At first glance, this goal appears ambitious, for it represents a doubling of China’s current nuclear capacity of 29 GW (as of May 2016, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) Power Reactor Information System (PRIS) database). -

Process Industry in China Future Developement and Government Regulation by Gao Peng and Lin Song, Innovation Norway, China

Process Industry in China Future developement and government regulation by Gao Peng and Lin Song, Innovation Norway, China Condensed report Kapittel 2 Table of contents Table of contents ............................................................................................................................................. ii Executive summary ......................................................................................................................................... iii Preface ........................................................................................................................................................... vi Acronyms and abbreviations ......................................................................................................................... vii 1. China’s process industry in general ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Chinese Process Industry brief introduction ................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Some of the relevant process industries’ development............................................................................... 2 1.3 Cooperation with Norway ............................................................................................................................ 3 1.4 Influence from the trade war with US-in China’s perspective ..................................................................... 3 1.5 Influence from COVID-19 -

Reform Is in the Pipelines: Pipechina and the Restructuring of China's

REFORM IS IN THE PIPELINES: PIPECHINA AND THE RESTRUCTURING OF CHINA’S NATURAL GAS MARKET BY ERICA DOWNS AND SHENG YAN SEPTEMBER 2020 Key Takeaways Beijing launched the most ambitious reform of China’s oil and natural gas industry in more than two decades with the establishment of the China Oil & Gas Piping Network Corporation (PipeChina) last December. The company is being developed from midstream assets— pipelines, liquified natural gas (LNG) import terminals, and storage facilities—and personnel transferred from China’s national oil companies (NOCs). Beijing expects that its goals of increasing China’s domestic and imported natural gas supplies and consumption will be more effectively advanced by having China’s midstream infrastructure owned and operated by a single company that provides fair and open access to its pipelines, LNG import terminals, and storage facilities instead of by three NOCs reluctant to grant third-party access to infrastructure. The specific objectives Beijing intends for PipeChina to further include: ● Growing China’s natural gas output by expanding the number of companies involved in the upstream (exploration and production) ● Reducing natural gas prices and increasing natural gas use by creating a more competitive downstream (processing, sales and distribution) ● Developing a unified national pipeline network to more efficiently distribute natural gas around the country If PipeChina delivers these outcomes—which depends, in part, on the enforcement of third- party access rules—there is likely to be an increasing number of new participants in China’s natural gas markets, especially LNG importers, which in turn should create new opportunities for LNG exporters. Introduction On December 9, 2019, Beijing legally established a new player in China’s oil and natural gas industry, the China Oil & Gas Piping Network Corporation (PipeChina).