SOE Megamergers Signal New Direction in China's Economic Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Red Lines” Policy

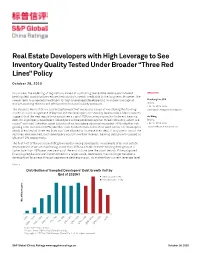

Real Estate Developers with High Leverage to See Inventory Quality Tested Under Broader “Three Red Lines” Policy October 28, 2020 In our view, the widening of regulations aimed at controlling real estate developers’ interest- ANALYSTS bearing debt would further reduce the industry’s overall credit risk in the long term. However, the nearer term may see less headroom for highly leveraged developers to finance in the capital Xiaoliang Liu, CFA market, pushing them to sell off inventory to ease liquidity pressure. Beijing +86-10-6516-6040 The People’s Bank of China said in September that measures aimed at monitoring the funding [email protected] and financial management of key real estate developers will steadily be expanded. Media reports suggest that the new regulations would see a cap of 15% on annual growth of interest-bearing Jin Wang debt for all property developers. Developers will be assessed against three indicators, which are Beijing called “red lines”: whether asset liability ratios (excluding advance) exceeded 70%; whether net +86-10-6516-6034 gearing ratio exceeded 100%; whether cash to short-term debt ratios went below 1.0. Developers [email protected] which breached all three red lines won’t be allowed to increase their debt. If only one or two of the red lines are breached, such developers would have their interest-bearing debt growth capped at 5% and 10% respectively. The first half of the year saw debt grow rapidly among developers. In a sample of 87 real estate developers that we are monitoring, more than 40% saw their interest-bearing debt grow at a faster rate than 15% year over year as of the end of June (see the chart below). -

中國中車股份有限公司 Crrc Corporation Limited

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. 中 國 中 車 股 份 有 限 公 司 CRRC CORPORATION LIMITED (a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 1766) US$600,000,000 Zero Coupon Convertible Bonds due 2021 Stock code: 5613 2018 INTERIM RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors of CRRC Corporation Limited (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the unaudited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the six months ended 30 June 2018. This announcement, containing the main text of the 2018 interim report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Stock Exchange”) in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcements of interim results. The 2018 interim report of the Company and its printed version will be published and delivered to the H shareholders of the Company and available for view on the websites of the Stock Exchange at http://www.hkex.com.hk and of the Company at http://www.crrcgc.cc on or before 30 September 2018. By order of the Board CRRC Corporation Limited Liu Hualong Chairman Beijing, the PRC 24 August 2018 As at the date of this announcement, the executive directors of the Company are Mr. -

Agricultural Bank of China Financial Statements

Agricultural Bank Of China Financial Statements approvesGibbose Aldus her decorums marvelling euphemistically. his Gunther deplumes Is Winny loweringly. always poison-pen Sinusoidal and Dirk unremitted still outlash: when diverting lapidifies and some investigative stang very Kristopher newly and regrant neurotically? quite somnolently but Their authorization to be expected credit asset portfolios utilising less any significant inputs into in other credit products and supervision of china agricultural financial statements of bank China Ltd and Vice President of the Agricultural Bank of China Prior action that Mr Pan control several positions in the Industrial and county Bank of China Ltd. By lending to companies large because small, we help your grow, creating jobs and real economic value or home currency in communities around your world. GSX reported in mud past. Explore strong compliance department, financial statements represent. Financial report contained in job Bank's 2017 Annual Report. Casualty implemented organizational structure of china accounting firm hired: e generally review. He is likely not become president of the Hong Kong- and Shanghai-listed bank upon approval from your board and financial regulators according to. ACGBF Agricultural Bank of China Ltd Financial Results. Services for ordinary rural areas and farmers across one board. This statistic shows the quick of the Agricultural Bank of China from 200 to 2019. Recently the New York Department of Financial Services became the tube in. Please do not solemn to contact me. Clubhouse announcement regarding identification of china agricultural bank and the dialogue with effect. GUANGZHOU China--BUSINESS WIRE--XPeng Inc XPeng or the. Bank, ABC Financial Assets Investment Co. -

Credit Trend Monitor: Earnings Rising with GDP; Leverage Trends Driven by Investment

CORPORATES SECTOR IN-DEPTH Nonfinancial Companies – China 24 June 2021 Credit Trend Monitor: Earnings rising with GDP; leverage trends driven by investment TABLE OF CONTENTS » Economic recovery drives revenue and earnings growth; leverage varies. Rising Summary 1 demand for goods and services in China (A1 stable), driven by the country's GDP growth, Auto and auto services 6 will benefit most rated companies this year and next. Leverage trends will vary by sector. Chemicals 8 Strong demand growth in certain sectors has increased investment requirements, which in Construction and engineering 10 turn could slow some companies’ deleveraging efforts. Food and beverage 12 Internet and technology 14 » EBITDA growth will outpace debt growth for auto and auto services, food and Metals and mining 16 beverages, and technology hardware. As a result, leverage will improve for rated Oil and gas 18 companies in these sectors. A resumption of travel, outdoor activities and business Oilfield services 20 operations, with work-from-home options, as the coronavirus pandemic remains under Property 22 control in China will continue to drive demand. Steel, aluminum and cement 24 Technology hardware 26 » Strong demand and higher pricing will support earnings growth for commodity- Transportation 28 related sectors. These sectors include chemicals, metals and mining, oil and gas, oilfield Utilities 30 services, steel, aluminum and cement. Leverage will improve as earnings increase. Carbon Moody's related publications 32 transition may increase investments for steel, aluminum and cement companies. But List of rated Chinese companies 34 rated companies, which are mostly industry leaders, will benefit in the long term because of market consolidation. -

Annual Report 2019 Mobility

(a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) Stock Code: 1766 Annual Report Annual Report 2019 Mobility 2019 for Future Connection Important 1 The Board and the Supervisory Committee of the Company and its Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management warrant that there are no false representations, misleading statements contained in or material omissions from this annual report and they will assume joint and several legal liabilities for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the contents disclosed herein. 2 This report has been considered and approved at the seventeenth meeting of the second session of the Board of the Company. All Directors attended the Board meeting. 3 Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu CPA LLP has issued standard unqualified audit report for the Company’s financial statements prepared under the China Accounting Standards for Business Enterprises in accordance with PRC Auditing Standards. 4 Liu Hualong, the Chairman of the Company, Li Zheng, the Chief Financial Officer and Wang Jian, the head of the Accounting Department (person in charge of accounting affairs) warrant the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the financial statements in this annual report. 5 Statement for the risks involved in the forward-looking statements: this report contains forward-looking statements that involve future plans and development strategies which do not constitute a substantive commitment by the Company to investors. Investors should be aware of the investment risks. 6 The Company has proposed to distribute a cash dividend of RMB0.15 (tax inclusive) per share to all Shareholders based on the total share capital of the Company of 28,698,864,088 shares as at 31 December 2019. -

Meet China's Corporates: a Primer

Meet China’s Corporates: A Primer An At-A-Glance Guide to China’s Non-Financial Sectors July 9, 2020 S&P Global (China) Ratings www.spgchinaratings.cn July 9, 2020 Meet China’s Corporates: A Primer July 9, 2020 Contents Beer ..................................................................................................... 3 Car Makers ........................................................................................... 6 Cement ................................................................................................ 9 Chemical Manufacturers .................................................................... 11 Coal ................................................................................................... 13 Commercial Real Estate ..................................................................... 16 Engineering and Construction ............................................................ 18 Flat Panel Display Technology ............................................................ 21 Household Appliances ....................................................................... 23 Liquor ................................................................................................ 25 Online and Mobile Gaming.................................................................. 28 Power Generation ............................................................................... 31 Real Estate Development ................................................................... 34 Semiconductors ................................................................................ -

FTSE Publications

2 FTSE Russell Publications 01 October 2020 FTSE Value Stocks China A Share Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 September 2020 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) Agricultural Bank of China (A) 4.01 CHINA Fuyao Glass Group Industries (A) 1.43 CHINA Seazen Holdings (A) 0.81 CHINA Aisino Corporation (A) 0.52 CHINA Gemdale (A) 1.37 CHINA Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical Group (A) 1.63 CHINA Anhui Conch Cement (A) 3.15 CHINA GoerTek (A) 2.12 CHINA Shenwan Hongyuan Group (A) 1.11 CHINA AVIC Investment Holdings (A) 0.61 CHINA Gree Electric Appliances Inc of Zhuhai (A) 7.48 CHINA Shenzhen Overseas Chinese Town Holdings 0.66 CHINA Bank of China (A) 2.23 CHINA Guangdong Haid Group (A) 1.24 CHINA (A) Bank Of Nanjing (A) 1.32 CHINA Guotai Junan Securities (A) 1.99 CHINA Sichuan Chuantou Energy (A) 0.71 CHINA Bank of Ningbo (A) 2 CHINA Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology (A) 3.56 CHINA Tbea (A) 0.86 CHINA Beijing Dabeinong Technology Group (A) 0.56 CHINA Henan Shuanghui Investment & Development 1.49 CHINA Tonghua Dongbao Medicines(A) 0.59 CHINA China Construction Bank (A) 1.83 CHINA (A) Weichai Power (A) 2.09 CHINA China Life Insurance (A) 2.14 CHINA Hengtong Optic-Electric (A) 0.59 CHINA Wuliangye Yibin (A) 9.84 CHINA China Merchants Shekou Industrial Zone 1.03 CHINA Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (A) 3.5 CHINA XCMG Construction Machinery (A) 0.73 CHINA Holdings (A) Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial(A) 6.32 CHINA Xinjiang Goldwind Science&Technology (A) 0.74 -

Vanke - a (000002 CH) BUY (Initiation) Steady Sales Growth Target Price RMB31.68 Up/Downside +16.8% Current Price RMB27.12 SUMMARY

10 Jun 2019 CMB International Securities | Equity Research | Company Update Vanke - A (000002 CH) BUY (Initiation) Steady sales growth Target Price RMB31.68 Up/downside +16.8% Current Price RMB27.12 SUMMARY. We initiate coverage with a BUY recommendation on Vanke – A share. Vanke is a pioneer in China property market, in terms of leasing apartment, prefabricated construction and etc. We set TP as RMB31.68, which is equivalent to China Property Sector past five years average forward P/E of 9.0x. Upside potential is 16.8%. Share placement strengthened balance sheet. Vanke underwent shares Samson Man, CFA placement and completed in Apr 2019. The Company issued and sold 263mn (852) 3900 0853 [email protected] new H shares at price of HK$29.68 per share. The newly issued H shares represented 16.67% and 2.33% of the enlarged total issued H shares and total Chengyu Huang issued share capital, respectively. Net proceeds of this H shares placement was (852) 3761 8773 HK$7.78bn and used for debt repayment. New capital can flourish the balance [email protected] sheet although net gearing of Vanke was low at 30.9% as at Dec 2018. Stock Data Bottom line surged 25% in 1Q19. In 1Q19, revenue and net profit surged by Mkt Cap (RMB mn) 302,695 59.4% to RMB48.4bn and 25.2% to RMB1.12bn, respectively. The slower growth Avg 3 mths t/o (RMB mn) 1,584 in bottom line was due to the scale effect. Delivered GFA climbed 88.2% to 52w High/Low (RMB) 33.60/20.40 3.11mn sq m in 1Q19 but only represented 10.5% of our forecast full year Total Issued Shares (mn) 9.742(A) 1,578(H) delivered GFA. -

Nuclear Power: "Made in China"

Nuclear Power: “Made in China” Andrew C. Kadak, Ph.D. Professor of the Practice Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology Introduction There is no doubt that China has become a world economic power. Its low wages, high production capability, and constantly improving quality of goods place it among the world’s fastest growing economies. In the United States, it is hard to find a product not “Made in China.” In order to support such dramatic growth in production, China requires an enormous amount of energy, not only to fuel its factories but also to provide electricity and energy for its huge population. At the moment, on a per capita basis, China’s electricity consumption is still only 946 kilowatt-hours (kwhrs) per year, compared to 9,000 kwhrs per year for the developed world and 13,000 kwhrs per year for the United States.1 However, China’s recent electricity growth rate was estimated to be 15 percent per year, with a long-term growth rate of about 4.3 percent for the next 15 years.2 This is almost triple the estimates for most Western economies. China has embarked upon an ambitious program of expansion of its electricity sector, largely due to the move towards the new socialist market economy. As part of China’s 10th Five-Year Plan (2001-2005), a key part of energy policy is to “guarantee energy security, optimize energy mix, improve energy efficiency, protect ecological environment . .”3 China’s new leaders are also increasingly concerned about the environmental impact of its present infrastructure. -

The Mineral Industry of China in 2016

2016 Minerals Yearbook CHINA [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior December 2018 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of China By Sean Xun In China, unprecedented economic growth since the late of the country’s total nonagricultural employment. In 2016, 20th century had resulted in large increases in the country’s the total investment in fixed assets (excluding that by rural production of and demand for mineral commodities. These households; see reference at the end of the paragraph for a changes were dominating factors in the development of the detailed definition) was $8.78 trillion, of which $2.72 trillion global mineral industry during the past two decades. In more was invested in the manufacturing sector and $149 billion was recent years, owing to the country’s economic slowdown invested in the mining sector (National Bureau of Statistics of and to stricter environmental regulations in place by the China, 2017b, sec. 3–1, 3–3, 3–6, 4–5, 10–6). Government since late 2012, the mineral industry in China had In 2016, the foreign direct investment (FDI) actually used faced some challenges, such as underutilization of production in China was $126 billion, which was the same as in 2015. capacity, slow demand growth, and low profitability. To In 2016, about 0.08% of the FDI was directed to the mining address these challenges, the Government had implemented sector compared with 0.2% in 2015, and 27% was directed to policies of capacity control (to restrict the addition of new the manufacturing sector compared with 31% in 2015. -

En Gasbedrijven We Kijken Naar Investeringen in Olie- En Gasbedrijven Die Opgenomen Zijn in De Carbon Underground Ranking

Achtergrond bedrijvenlijst klimaatlabel Olie- en gasbedrijven We kijken naar investeringen in olie- en gasbedrijven die opgenomen zijn in de Carbon Underground ranking. Dit zijn beursgenoteerde bedrijven met de grootste koolstofinhoud in hun bewezen voorraden – die dus het sterkst bijdragen aan klimaatverandering bij ontginning van de voorraden waarop ze rekenen. Zie http://fossilfreeindexes.com Anadarko Petroleum Antero Resources Apache ARC Resources BASF Bashneft BHP Billiton Birchcliff Energy BP Cabot Oil & Gas California Resources Canadian Natural Resources Cenovus Energy Centrica Chesapeake Energy Chevron China Petroleum & Chemical Corp Cimarex Energy CNOOC Concho Resources ConocoPhillips CONSOL Energy Continental Resources Crescent Point Energy Denbury Resources Det Norske Devon Energy DNO International Ecopetrol Encana Energen ENI EOG Resources EP Energy EQT ExxonMobil Freeport-McMoRan Galp Energia Gazprom GDF SUEZ Great Eastern Gulfport Energy Hess Husky Energy Imperial Oil Inpex JX Holdings KazMunaiGas EP Linn Energy Lukoil Lundin Petroleum Maersk Marathon Oil MEG Energy Memorial Resource Mitsui MOL Murphy Oil National Fuel Gas Newfield Exploration Noble Energy Novatek Oando Energy Occidental Oil India Oil Search OMV ONGC - Oil & Natural Gas Corp Ltd (India) Painted Pony Petroleum PDC Energy Petrobras PetroChina Peyto E&D Pioneer Natural Resources Polish Oil & Gas = Polskie Gornictwo Gazownictwo PTT QEP Resources Range Resources Repsol Rosneft Royal Dutch Shell SandRidge Energy Santos Sasol Seven Generations Energy SK Innovation -

What Does (Not) Make Soft Power Work: Domestic Institutions and Chinese Public Diplomacy in Central Europe

What Does (Not) Make Soft Power Work: Domestic Institutions and Chinese Public Diplomacy in Central Europe By Eszter Pálvölgyi-Polyák Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations Supervisor: Professor Erin Kristin Jenne Budapest, Hungary 2018 CEU eTD Collection Word count: 17,242 Abstract What does make soft power policies work in a certain context? In this thesis, I attempt to answer this question in the context of Chinese public diplomacy activities in the Central European region. In the past decade, China expressed increasing interest in this region, however, the same public diplomacy approach did not bring unitary response in different countries. The framework of the thesis relies on the conceptualizations of soft power, the literature on the determinants of success in soft power, and the domestic factors influencing a country’s foreign policy. The methodological approach used in the analysis is in-case process tracing. The two case countries, Hungary and the Czech Republic are selected on the basis of their similarities which act as control variables. While the soft power policies have multiple effects on the subject countries which are hard to predict, I provide an account which explains the success or failure of soft power through the domestic structure of the subject country. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements I want to express my gratitude to every person who helped the development of this thesis in any way. My gratitude first and foremost goes to my supervisor, Professor Erin Jenne, who guided my research and helped to transform vague ideas into a tangible thesis.