War and Peace Anthony Briggs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problems of Mimetic Characterization in Dostoevsky and Tolstoy

Illusion and Instrument: Problems of Mimetic Characterization in Dostoevsky and Tolstoy By Chloe Susan Liebmann Kitzinger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Irina Paperno, Chair Professor Eric Naiman Professor Dorothy J. Hale Spring 2016 Illusion and Instrument: Problems of Mimetic Characterization in Dostoevsky and Tolstoy © 2016 By Chloe Susan Liebmann Kitzinger Abstract Illusion and Instrument: Problems of Mimetic Characterization in Dostoevsky and Tolstoy by Chloe Susan Liebmann Kitzinger Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Irina Paperno, Chair This dissertation focuses new critical attention on a problem central to the history and theory of the novel, but so far remarkably underexplored: the mimetic illusion that realist characters exist independently from the author’s control, and even from the constraints of form itself. How is this illusion of “life” produced? What conditions maintain it, and at what points does it start to falter? My study investigates the character-systems of three Russian realist novels with widely differing narrative structures — Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1865–1869), and Dostoevsky’s The Adolescent (1875) and The Brothers Karamazov (1879–1880) — that offer rich ground for exploring the sources and limits of mimetic illusion. I suggest, moreover, that Tolstoy and Dostoevsky themselves were preoccupied with this question. Their novels take shape around ambitious projects of characterization that carry them toward the edges of the realist tradition, where the novel begins to give way to other forms of art and thought. -

The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte's Invasion

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2012 “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London imesT Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia Julia Dittrich East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dittrich, Julia, "“We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1457. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1457 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia _______________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _______________________ by Julia Dittrich August 2012 _______________________ Dr. Stephen G. Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry J. Antkiewicz Dr. Brian J. Maxson Keywords: Napoleon Bonaparte, The London Times, English Identity ABSTRACT “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia by Julia Dittrich “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia aims to illustrate how The London Times interpreted and reported on Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia. -

Annual Report (Abridged)

2015 Department of Records (DoR) Annual Report (Abridged) Note: This is an abridged version of the report. Due to it being published in the winter of 2017, some data is not included as it is updated in real time and does not stay the same as the data at the end of a year does in some reports. We apologize for this and will be sure the missing sections are included in next year’s report. Napoleonic Wargames Club Popular Games and Scenarios: Games Game Battles* Campaign Waterloo (HPS) 407 Campaign Leipzig (JTS) 343 Campaign Eckmühl (HPS) 182 Campaign Austerlitz (HPS) 161 Napoleon's Russian Campaign (HPS) 111 Campaign Jena-Auerstedt (HPS) 103 Campaign Wagram (HPS) 72 Napoleon In Russia (Talonsoft) 65 Bonaparte's Peninsular War (JTS) 63 Campaign Bautzen (JTS) 58 Campaign 1814 (JTS) 54 Battleground Waterloo (Talonsoft) 43 Prelude To Waterloo (Talonsoft) 39 Les Grognards (HistWar) 30 Napoleon's Campaigns (AGEOD) 10 Commander: Napoleon At War 5 Crown of Glory: Emperor's Edition 5 Les Grognards (HistWar) - old version 3 Napoleonic Wargames Club (NWC) © 2016 Battleground Waterloo (Talonsoft, French version) 2 Egypt (mod) 1 The Eagle has Landed (Andy Barns) 0 Crown of Glory 0 Napoleon at Golymin (Greg Gorsuch) 0 Battlefield Eylau (Greg Gorsuch) 0 All 1757 Scenarios** Scenario Battles* The Waterloo Campaign, June 1815 43 The Battle of Quatre Bras - Historical, June 16, 1815 38 Hypothetical battles - v 10 35 #22H. The Battle of Austerlitz (HTH) 32 07. Kutuzov Turns to Fight 27 The Ridge - D'Erlon's Attack - Phase 1 23 14. The Battle of Waterloo 22 The Fall Campaign of 1813 22 Custom scenario 21 Waterloo - Historical 19 002. -

War & Peace by Helen Edmundson

War & Peace by Helen Edmundson from the novel by Leo Tolstoy Education Pack by Gillian King Photo: Alistair Muir | Rehearsal Photography: Ellie Kurttz | Designed by www.stemdesign.co.uk Contents • The Pack........................................................................................... 03 • Shared Experience Expressionism.............................................................. 04 • Summary of War & Peace........................................................................ 05 • Helen Edmundson on the Adaptation Process................................................. 07 • Ideas inspired by the research trip to Russia................................................. 08 • Tolstoy’s Russia.................................................................................... 09 • Leo Tolstoy Biography............................................................................. 10 • Playing the Subtext................................................................................ 12 • What do I Want? (exploring character intentions)............................................ 14 • Napoleon’s 1812 Campaign in Russia........................................................... 17 • The Battle - Created through the Actors’ Physicality......................................... 19 • The Ensemble Process............................................................................ 20 • Russian Women...................................................................................... 22 • Is Man Nothing More Than a Puppet?.......................................................... -

The Memoirs of General the Baron De Marbot in 2 Volumes

The Memoirs of General the Baron de Marbot in 2 Volumes by the Baron de Marbot THE MEMOIRS OF GENERAL THE BARON DE MARBOT. Table of Contents THE MEMOIRS OF GENERAL THE BARON DE MARBOT......................................1 Volume I....................................................................2 Introduction...........................................................2 Chap. 1................................................................6 Chap. 2...............................................................11 Chap. 3...............................................................17 Chap. 4...............................................................24 Chap. 5...............................................................31 Chap. 6...............................................................39 Chap. 7...............................................................41 Chap. 8...............................................................54 Chap. 9...............................................................67 Chap. 10..............................................................75 Chap. 11..............................................................85 Chap. 12..............................................................96 Chap. 13.............................................................102 Chap. 14.............................................................109 Chap. 15.............................................................112 Chap. 16.............................................................122 Chap. 17.............................................................132 -

Animals Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 2

AAnniimmaallss LLiibbeerraattiioonn PPhhiilloossoopphhyy aanndd PPoolliiccyy JJoouurrnnaall VVoolluummee 55,, IIssssuuee 22 -- 22000077 Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 2 2007 Edited By: Steven Best, Chief Editor ____________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Lev Tolstoy and the Freedom to Choose One’s Own Path Andrea Rossing McDowell Pg. 2-28 Jewish Ethics and Nonhuman Animals Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 29-47 Deliberative Democracy, Direct Action, and Animal Advocacy Stephen D’Arcy Pg. 48-63 Should Anti-Vivisectionists Boycott Animal-Tested Medicines? Katherine Perlo Pg. 64-78 A Note on Pedagogy: Humane Education Making a Difference Piers Bierne and Meena Alagappan Pg. 79-94 BOOK REVIEWS _________________ Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal, by Eric Schlosser (2005) Reviewed by Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 95-101 Eternal Treblinka: Our Treatment of Animals and the Holocaust, by Charles Patterson (2002) Reviewed by Steven Best Pg. 102-118 The Longest Struggle: Animal Advocacy from Pythagoras to PETA, by Norm Phelps (2007) Reviewed by Steven Best Pg. 119-130 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume V, Issue 2, 2007 Lev Tolstoy and the Freedom to Choose One’s Own Path Andrea Rossing McDowell, PhD It is difficult to be sat on all day, every day, by some other creature, without forming an opinion about them. On the other hand, it is perfectly possible to sit all day every day, on top of another creature and not have the slightest thought about them whatsoever. -- Douglas Adams, Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency (1988) Committed to the idea that the lives of humans and animals are inextricably linked, Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (1828–1910) promoted—through literature, essays, and letters—the animal world as another venue in which to practice concern and kindness, consequently leading to more peaceful, consonant human relations. -

Unpalatable Pleasures: Tolstoy, Food, and Sex

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Scholarship Languages, Literatures, and Cultures 1993 Unpalatable Pleasures: Tolstoy, Food, and Sex Ronald D. LeBlanc University of New Hampshire - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/lang_facpub Recommended Citation Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. Tolstoy’s Pierre Bezukhov: A Psychoanalytic Study. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1993. Critiques: Brett Cooke, Ronald LeBlanc, Duffield White, James Rice. Reply: Daniel Rancour- Laferriere. Volume VII, 1994, pp. 70-93. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW ~·'T'::'1r"'T,n.1na rp.llHlrIP~ a strict diet. There needs to'be a book about food. L.N. Tolstoy times it seems to me as if the Russian is a sort of lost soul. You want to do and yet you can do nothing. You keep thinking that you start a new life as of tomorrow, that you will start a new diet as of tomorrow, but of the sort happens: by the evening of that 'very same you have gorged yourself so much that you can only blink your eyes and you cannot even move your tongue. N.V. Gogol Russian literature is mentioned, one is likely to think almost instantly of that robust prose writer whose culinary, gastronomic and alimentary obsessions--in his verbal art as well as his own personal life- often reached truly gargantuan proportions. -

Living with Death: the Humanity in Leo Tolstoy's Prose Dr. Patricia A. Burak Yuri Pavlov

Living with Death: The Humanity in Leo Tolstoy’s Prose A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Renée Crown University Honors Program at Syracuse University Liam Owens Candidate for Bachelor of Science in Biology and Renée Crown University Honors Spring 2020 Honors Thesis in Your Major Thesis Advisor: _______________________ Dr. Patricia A. Burak Thesis Reader: _______________________ Yuri Pavlov Honors Director: _______________________ Dr. Danielle Smith, Director Abstract What do we fear so uniquely as our own death? Of what do we know less than the afterlife? Leo Tolstoy was quoted saying: “We can only know that we know nothing. And that is the highest degree of human wisdom.” Knowing nothing completely contradicts the essence of human nature. Although having noted the importance of this unknowing, using the venture of creative fiction, Tolstoy pined ceaselessly for an understanding of the experience of dying. Tolstoy was afraid of death; to him it was an entity which loomed. I believe his early involvements in war, as well as the death of his brother Dmitry, and the demise of his self-imaged major character Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, whom he tirelessly wrote and rewrote—where he dove into the supposed psyche of a dying man—took a toll on the author. Tolstoy took the plight of ending his character’s life seriously, and attempted to do so by upholding his chief concern: the truth. But how can we, as living, breathing human beings, know the truth of death? There is no truth we know of it other than its existence, and this alone is cause enough to scare us into debilitating fits and ungrounded speculation. -

King-Salter2020.Pdf (1.693Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Dostoevsky’s Storm and Stress Notes from Underground and the Psychological Foundations of Utopia John Luke King-Salter PhD Comparative Literature University of Edinburgh 2019 Lay Summary The goal of this dissertation is to combine philosophical and literary scholarship to arrive at a new interpretation of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. In this novel, Dostoevsky argues against the Russian socialists of the early 1860s, and attacks their ideal of a socialist utopia in particular. Dostoevsky’s argument is obscure and difficult to understand, but it seems to depend upon the way he understands the interaction between psychology and politics, or, in other words, the way in which he thinks the health of a society depends upon the psychological health of its members. It is usually thought that Dostoevsky’s problem with socialism is that it curtails individual liber- ties to an unacceptable degree, and that the citizens of a socialist utopia would be frustrated by the lack of freedom. -

Sample Pages

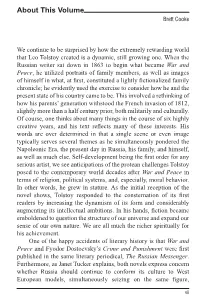

About This Volume Brett Cooke We continue to be surprised by how the extremely rewarding world WKDW/HR7ROVWR\FUHDWHGLVDG\QDPLFVWLOOJURZLQJRQH:KHQWKH Russian writer sat down in 1863 to begin what became War and PeaceKHXWLOL]HGSRUWUDLWVRIfamily members, as well as images RIKLPVHOILQZKDWDW¿UVWFRQVWLWXWHGDOLJKWO\¿FWLRQDOL]HGfamily chronicle; he evidently used the exercise to consider how he and the SUHVHQWVWDWHRIKLVFRXQWU\FDPHWREH7KLVLQYROYHGDUHWKLQNLQJRI KRZKLVSDUHQWV¶JHQHUDWLRQZLWKVWRRGWKH)UHQFKLQYDVLRQRI slightly more than a half century prior, both militarily and culturally. Of course, one thinks about many things in the course of six highly FUHDWLYH \HDUV DQG KLV WH[W UHÀHFWV PDQ\ RI WKHVH LQWHUHVWV +LV words are over determined in that a single scene or even image typically serves several themes as he simultaneously pondered the Napoleonic Era, the present day in Russia, his family, and himself, DVZHOODVPXFKHOVH6HOIGHYHORSPHQWEHLQJWKH¿UVWRUGHUIRUDQ\ VHULRXVDUWLVWZHVHHDQWLFLSDWLRQVRIWKHSURWHDQFKDOOHQJHV7ROVWR\ posed to the contemporary world decades after War and Peace in terms of religion, political systems, and, especially, moral behavior. In other words, he grew in stature. As the initial reception of the QRYHO VKRZV 7ROVWR\ UHVSRQGHG WR WKH FRQVWHUQDWLRQ RI LWV ¿UVW readers by increasing the dynamism of its form and considerably DXJPHQWLQJLWVLQWHOOHFWXDODPELWLRQV,QKLVKDQGV¿FWLRQEHFDPH emboldened to question the structure of our universe and expand our sense of our own nature. We are all much the richer spiritually for his achievement. One of the happy accidents of literary history is that War and Peace and Fyodor 'RVWRHYVN\¶VCrime and PunishmentZHUH¿UVW published in the same literary periodical, The Russian Messenger. )XUWKHUPRUHDV-DQHW7XFNHUH[SODLQVERWKQRYHOVH[SUHVVFRQFHUQ whether Russia should continue to conform its culture to West (XURSHDQ PRGHOV VLPXOWDQHRXVO\ VHL]LQJ RQ WKH VDPH ¿JXUH vii Napoleon Bonaparte, in one case leading a literal invasion of the country, in the other inspiring a premeditated murder. -

Dvigubski Full Dissertation

The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Anna Dvigubski All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski This dissertation examines representations of authorship in Russian literature from a number of perspectives, including the specific Russian cultural context as well as the broader discourses of romanticism, autobiography, and narrative theory. My main focus is a narrative device I call “the figured author,” that is, a background character in whom the reader may recognize the author of the work. I analyze the significance of the figured author in the works of several Russian nineteenth- and twentieth- century authors in an attempt to understand the influence of culture and literary tradition on the way Russian writers view and portray authorship and the self. The four chapters of my dissertation analyze the significance of the figured author in the following works: 1) Pushkin's Eugene Onegin and Gogol's Dead Souls; 2) Chekhov's “Ariadna”; 3) Bulgakov's “Morphine”; 4) Nabokov's The Gift. In the Conclusion, I offer brief readings of Kharms’s “The Old Woman” and “A Fairy Tale” and Zoshchenko’s Youth Restored. One feature in particular stands out when examining these works in the Russian context: from Pushkin to Nabokov and Kharms, the “I” of the figured author gradually recedes further into the margins of narrative, until this figure becomes a third-person presence, a “he.” Such a deflation of the authorial “I” can be seen as symptomatic of the heightened self-consciousness of Russian culture, and its literature in particular. -

Tolstoy in Prerevolutionary Russian Criticism

Tolstoy in Prerevolutionary Russian Criticism BORIS SOROKIN TOLSTOY in Prerevolutionary Russian Criticism PUBLISHED BY THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS FOR MIAMI UNIVERSITY Copyright ® 1979 by Miami University All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Sorokin, Boris, 1922 Tolstoy in prerevolutionary Russian criticism. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Tolstoi, Lev Nikolaevich, graf, 1828-1910—Criticism and interpretation—History. 2. Criticism—Russia. I. Title. PG3409.5.S6 891.7'3'3 78-31289 ISBN 0-8142-0295-0 Contents Preface vii 1/ Tolstoy and His Critics: The Intellectual Climate 3 2/ The Early Radical Critics 37 3/ The Slavophile and Organic Critics 71 4/ The Aesthetic Critics 149 5/ The Narodnik Critics 169 6/ The Symbolist Critics 209 7/ The Marxist Critics 235 Conclusion 281 Notes 291 Bibliography 313 Index 325 PREFACE Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) has been described as the most momen tous phenomenon of Russian life during the nineteenth century.1 Indeed, in his own day, and for about a generation afterward, he was an extraordinarily influential writer. During the last part of his life, his towering personality dominated the intellectual climate of Russia and the world to an unprecedented degree. His work, moreover, continues to be studied and admired. His views on art, literature, morals, politics, and life have never ceased to influence writers and thinkers all over the world. Such interest over the years has produced an immense quantity of books and articles about Tolstoy, his ideas, and his work. In Russia alone their number exceeded ten thousand some time ago (more than 5,500 items were published in the Soviet Union between 1917 and 1957) and con tinues to rise.