Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2D6 Substrates 2D6 Inhibitors 2D6 Inducers

Physician Guidelines: Drugs Metabolized by Cytochrome P450’s 1 2D6 Substrates Acetaminophen Captopril Dextroamphetamine Fluphenazine Methoxyphenamine Paroxetine Tacrine Ajmaline Carteolol Dextromethorphan Fluvoxamine Metoclopramide Perhexiline Tamoxifen Alprenolol Carvedilol Diazinon Galantamine Metoprolol Perphenazine Tamsulosin Amiflamine Cevimeline Dihydrocodeine Guanoxan Mexiletine Phenacetin Thioridazine Amitriptyline Chloropromazine Diltiazem Haloperidol Mianserin Phenformin Timolol Amphetamine Chlorpheniramine Diprafenone Hydrocodone Minaprine Procainamide Tolterodine Amprenavir Chlorpyrifos Dolasetron Ibogaine Mirtazapine Promethazine Tradodone Aprindine Cinnarizine Donepezil Iloperidone Nefazodone Propafenone Tramadol Aripiprazole Citalopram Doxepin Imipramine Nifedipine Propranolol Trimipramine Atomoxetine Clomipramine Encainide Indoramin Nisoldipine Quanoxan Tropisetron Benztropine Clozapine Ethylmorphine Lidocaine Norcodeine Quetiapine Venlafaxine Bisoprolol Codeine Ezlopitant Loratidine Nortriptyline Ranitidine Verapamil Brofaramine Debrisoquine Flecainide Maprotline olanzapine Remoxipride Zotepine Bufuralol Delavirdine Flunarizine Mequitazine Ondansetron Risperidone Zuclopenthixol Bunitrolol Desipramine Fluoxetine Methadone Oxycodone Sertraline Butylamphetamine Dexfenfluramine Fluperlapine Methamphetamine Parathion Sparteine 2D6 Inhibitors Ajmaline Chlorpromazine Diphenhydramine Indinavir Mibefradil Pimozide Terfenadine Amiodarone Cimetidine Doxorubicin Lasoprazole Moclobemide Quinidine Thioridazine Amitriptyline Cisapride -

Appendix 13C: Clinical Evidence Study Characteristics Tables

APPENDIX 13C: CLINICAL EVIDENCE STUDY CHARACTERISTICS TABLES: PHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS Abbreviations ............................................................................................................ 3 APPENDIX 13C (I): INCLUDED STUDIES FOR INITIAL TREATMENT WITH ANTIPSYCHOTIC MEDICATION .................................. 4 ARANGO2009 .................................................................................................................................. 4 BERGER2008 .................................................................................................................................... 6 LIEBERMAN2003 ............................................................................................................................ 8 MCEVOY2007 ................................................................................................................................ 10 ROBINSON2006 ............................................................................................................................. 12 SCHOOLER2005 ............................................................................................................................ 14 SIKICH2008 .................................................................................................................................... 16 SWADI2010..................................................................................................................................... 19 VANBRUGGEN2003 .................................................................................................................... -

Mechanisms of Action of Antipsychotic Drugs Of

302 Current Neuropharmacology, 2009, 7, 302-314 Mechanisms of Action of Antipsychotic Drugs of Different Classes, Refractoriness to Therapeutic Effects of Classical Neuroleptics, and Individual Variation in Sensitivity to their Actions: PART I R. Miller* Otago Centre for Theoretical Studies in Psychiatry and Neuroscience (OCTSPAN), Department of Anatomy and Struc- tural Biology, School of Medical Sciences, University of Otago, P.O.Box 913, Dunedin, New Zealand Abstract: Many issues remain unresolved about antipsychotic drugs. Their therapeutic potency scales with affinity for dopamine D2 receptors, but there are indications that they act indirectly, with dopamine D1 receptors (and others) as pos- sible ultimate targets. Classical neuroleptic drugs disinhibit striatal cholinergic interneurones and increase acetyl choline release. Their effects may then depend on stimulation of muscarinic receptors on principle striatal neurones (M4 recep- tors, with reduction of cAMP formation, for therapeutic effects; M1 receptors for motor side effects). Many psychotic pa- tients do not benefit from neuroleptic drugs, or develop resistance to them during prolonged treatment, but respond well to clozapine. For patients who do respond, there is a wide (>ten-fold) range in optimal doses. Refractoriness or low sensitiv- ity to antipsychotic effects (and other pathologies) could then arise from low density of cholinergic interneurones. Clozap- ine probably owes its special actions to direct stimulation of M4 receptors, a mechanism available when indirect action is lost. Key Words: Antipsychotic drugs, neuroleptic drugs, cholinergic interneurones, D1 receptors, D2 receptors, muscarinic M1 receptors, muscarinic M4 receptors, neuroleptic threshold, atypical antipsychotic agents. 1. INTRODUCTION these drugs. Guidelines for dosage, and dose equivalences between different drugs have been based on group averages The first antipsychotic drug - chlorpromazine - was dis- derived from dose-finding trials. -

Achat Viagra Puissant ### Ablation Prostate Et Viagra >>> Kvadridze.Github.Io

Viagra est indiquée pour le traitement de la dysfonction érectile masculine. >>> ORDER NOW <<< Achat viagra puissant Tags: ordonnance de viagra combien de temps dur viagra comment peut on se procurer du viagra efficacité viagra générique un site fiable pour acheter du viagra le viagra sur ordonnance danger dacheter du viagra sur internet prix cachet viagra combien coute le viagra au maroc le rôle de viagra peut acheter du viagra sans ordonnance quesque cest viagra composition de viagra acheter viagra paris sans ordonnance comment se procurer viagra sans ordonnance comment reconnaitre le faux viagra quand faut il prendre viagra comment acheter du viagra au quebec lancement du viagra quest ce que cest le viagra viagra pfizer mode demploi les conséquences du viagra edex plus viagra comment prendre de viagra forum viagra pas cher commande de viagra en ligne meme effet que viagra prendre la moitié dun viagra experience viagra femme A vaginal ring can slip out of the vagina. In the event of overdosage, general symptomatic and achat viagra puissant measures are indicated as required Resistance to azithromycin may be inherent or acquired. Comments: Take one pill a day. Ca 20 minuter senare börjar mina kollegor droppa in i ordningen: Susanne, Britt, Emma, Nina, Gunnel, Eva och sist Barbro. Epidemiologic investigations of this outbreak demonstrated that individuals in close contact with the index case or with exposure to poultry were at risk of being infected. 25 mg pour femme viagra cherche 2 weeks or until I "felt" like I could go lower. It might take a while to adapt to it, since it will lower your blood pressure. -

The Use of Stems in the Selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Pharmaceutical Substances

WHO/PSM/QSM/2006.3 The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances 2006 Programme on International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Quality Assurance and Safety: Medicines Medicines Policy and Standards The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances FORMER DOCUMENT NUMBER: WHO/PHARM S/NOM 15 © World Health Organization 2006 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

Comprehensive Review on the Interaction Between Natural Compounds and Brain Receptors: Benefits and Toxicity

European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 174 (2019) 87e115 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/ejmech Review article Comprehensive review on the interaction between natural compounds and brain receptors: Benefits and toxicity * Ana R. Silva a, Clara Grosso b, , Cristina Delerue-Matos b,Joao~ M. Rocha a, c a Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology (CBMA), Department of Biology (DB), University of Minho (UM), Campus Gualtar, P-4710-057, Braga, Portugal b REQUIMTE/LAQV, Instituto Superior de Engenharia do Instituto Politecnico do Porto, Rua Dr. Antonio Bernardino de Almeida, 431, P-4249-015, Porto, Portugal c REQUIMTE/LAQV, Grupo de investigaçao~ de Química Organica^ Aplicada (QUINOA), Laboratorio de polifenois alimentares, Departamento de Química e Bioquímica (DQB), Faculdade de Ci^encias da Universidade do Porto (FCUP), Rua do Campo Alegre, s/n, P-4169-007, Porto, Portugal article info abstract Article history: Given their therapeutic activity, natural products have been used in traditional medicines throughout the Received 6 December 2018 centuries. The growing interest of the scientific community in phytopharmaceuticals, and more recently Received in revised form in marine products, has resulted in a significant number of research efforts towards understanding their 10 April 2019 effect in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's (AD), Parkinson (PD) and Accepted 11 April 2019 Huntington (HD). Several studies have shown that many of the primary and secondary metabolites of Available online 17 April 2019 plants, marine organisms and others, have high affinities for various brain receptors and may play a crucial role in the treatment of diseases affecting the central nervous system (CNS) in mammalians. -

NIDA Drug Supply Program Catalog, 25Th Edition

RESEARCH RESOURCES DRUG SUPPLY PROGRAM CATALOG 25TH EDITION MAY 2016 CHEMISTRY AND PHARMACEUTICS BRANCH DIVISION OF THERAPEUTICS AND MEDICAL CONSEQUENCES NATIONAL INSTITUTE ON DRUG ABUSE NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES 6001 EXECUTIVE BOULEVARD ROCKVILLE, MARYLAND 20852 160524 On the cover: CPK rendering of nalfurafine. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Introduction ................................................................................................1 B. NIDA Drug Supply Program (DSP) Ordering Guidelines ..........................3 C. Drug Request Checklist .............................................................................8 D. Sample DEA Order Form 222 ....................................................................9 E. Supply & Analysis of Standard Solutions of Δ9-THC ..............................10 F. Alternate Sources for Peptides ...............................................................11 G. Instructions for Analytical Services .........................................................12 H. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis of Compounds .............................................13 I. Nicotine Research Cigarettes Drug Supply Program .............................16 J. Ordering Guidelines for Nicotine Research Cigarettes (NRCs)..............18 K. Ordering Guidelines for Marijuana and Marijuana Cigarettes ................21 L. Important Addresses, Telephone & Fax Numbers ..................................24 M. Available Drugs, Compounds, and Dosage Forms ..............................25 -

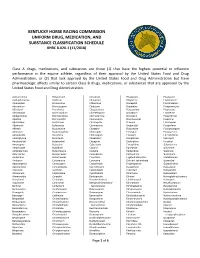

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

Astrazenecateva09252009

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit 2008-1480, -1481 ASTRAZENECA PHARMACEUTICALS LP and ASTRAZENECA UK LIMITED, Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC. and TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES, LTD., Defendants-Appellants, and SANDOZ, INC., Defendant-Appellant. Henry J. Renk, Fitzpatrick Cella, Harper & Scinto, of New York, New York, argued for plaintiffs-appellees. With him on the brief were Bruce C. Haas; Charles E. Lipsey, Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow Garrett & Dunner, LLP, of Reston, Virginia, and Thomas A. Stevens, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, of Wilmington, Delaware. Ira J. Levy, Goodwin Proctor LLP, of New York, New York, argued for defendants- appellants Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., et al. With him on the brief were Henry C. Dinger, Daryl L. Wiesen and John T. Bennett, of Boston, Massachusetts. Douglass C. Hochstetler, Schiff Hardin LLP, of Chicago, Illinois, argued for defendant- appellant Sandoz, Inc. With him on the brief were Jason G. Harp; and Beth D. Jacob, of New York, New York. Appealed from: United States District Court for the District of New Jersey Judge Joel A. Pisano United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit 2008-1480,-1481 ASTRAZENECA PHARMACEUTICALS LP and ASTRAZENECA UK LIMITED, Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC. and TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES, LTD., Defendants-Appellants, and SANDOZ, INC., Defendant-Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey in consolidated Case Nos. 05-CV-5333, 06-CV-1528, 07-CV-1632, and 07-CV-3001, Judge Joel A. Pisano. ___________________________ DECIDED: September 25, 2009 ___________________________ Before NEWMAN, RADER, and PROST Circuit Judges. NEWMAN, Circuit Judge. -

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 6,060,642 Tecott Et Al

US006060642A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 6,060,642 Tecott et al. (45) Date of Patent: May 9, 2000 54 SEROTONIN 5-HT6 RECEPTOR KNOCKOUT Roth, Bryan L., et al., “Binding of Typical and Atypical MOUSE Antipsychotic Agents 5-Hydroxytryptamine-6 and 5-Hydroxytryptamine–7 Receptors'." The Journal Of Phar 75 Inventors: Laurence H. Tecott, San Francisco; macology and Experimental Therapeutics (1994) vol. 268, Thomas J. Brennan, San Carlos, both No. (3):1403–1410. of Calif. Ruat, Martial, et al., “A Novel Rat Serotonin (5-HT) 73 Assignee: The Regents of the University of Receptor: Molecular Cloning, Localization And Stimulation Of cAMP Accumulation,” Biochemical and Biophysical California, Oakland, Calif. Communications Research Communications (May 28, 1993) 21 Appl. No.: 09/132,388 vol. 193, No. (1):268–276. Saudou, Frédéric, et al., “5-Hydroxytryptamine Receptor 22 Filed: Aug. 11, 1998 Subtypes. In Vertebrates And Inverterbrates,” Neurochem Int. (1994) vol. 25, No. (6):503–532. Related U.S. Application Data Sleight, A.J., et al., “Effects of Altered 5-HT Expression. In 60 Provisional application No. 60/055.817, Aug. 15, 1997. The Rat: Functional Studies Using Antisense Oligonucle 51 Int. Cl." ............................. C12N 5700; C12N 15/12; otides,” Behavioural Brain Research (1996) vol. AO1K 67/027; G01N 33/15; CO7H 21/04 73:245-248. 52 U.S. Cl. ................................... 800/3; 800/18; 800/21; Tecott, Laurence H., et al., “Behavioral Genetics: Genes And 800/9; 435/172.1; 435/1723; 435/325; Aggressiveness,” Current Biology (1996) vol. 6, No. 435/455; 536/23.5 (3):238–240. 58 Field of Search ................................... -

Implications of Dopamine D3 Receptor for Glaucoma: In-Silico and In-Vivo Studies

International PhD Program in Neuropharmacology XXVI Cycle Implications of dopamine D3 receptor for glaucoma: in-silico and in-vivo studies PhD thesis Chiara Bianca Maria Platania Coordinator: Prof. Salvatore Salomone Tutor: Prof. Claudio Bucolo Department of Clinical and Molecular Biomedicine Section of Pharmacology and Biochemistry. University of Catania - Medical School December 2013 Copyright ©: Chiara B. M. Platania - December 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................ 4 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................ 5 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................... 7 GLAUCOMA ................................................................................................ 9 Aqueous humor dynamics .................................................................. 10 Pharmacological treatments of glaucoma............................................ 12 Pharmacological perspectives in treatment of glaucoma ..................... 14 Animal models of glaucoma ............................................................... 18 G PROTEIN COUPLED RECEPTORS ....................................................... 21 GPCRs functions and structure ........................................................... 22 Molecular modeling of GPCRs ........................................................... 25 D2-like receptors ............................................................................... -

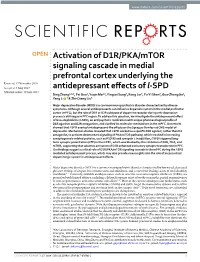

Activation of D1R/PKA/Mtor Signaling Cascade in Medial

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Activation of D1R/PKA/mTOR signaling cascade in medial prefrontal cortex underlying the Received: 17 November 2016 Accepted: 3 May 2017 antidepressant effects ofl -SPD Published: xx xx xxxx Bing Zhang1,2,3, Fei Guo1, Yuqin Ma1,2, Yingcai Song3, Rong Lin3, Fu-Yi Shen3, Guo-Zhang Jin1, Yang Li 1 & Zhi-Qiang Liu3 Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by diverse symptoms. Although several antidepressants can influence dopamine system in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), but the role of D1R or D2R subtypes of dopamine receptor during anti-depression process is still vague in PFC region. To address this question, we investigate the antidepressant effect of levo-stepholidine (l-SPD), an antipsychotic medication with unique pharmacological profile of D1R agonism and D2R antagonism, and clarified its molecular mechanisms in the mPFC. Our results showed that l-SPD exerted antidepressant-like effects on the Sprague-Dawley rat CMS model of depression. Mechanism studies revealed that l-SPD worked as a specific D1R agonist, rather than D2 antagonist, to activate downstream signaling of PKA/mTOR pathway, which resulted in increasing synaptogenesis-related proteins, such as PSD 95 and synapsin I. In addition, l-SPD triggered long- term synaptic potentiation (LTP) in the mPFC, which was blocked by the inhibition of D1R, PKA, and mTOR, supporting that selective activation of D1R enhanced excitatory synaptic transduction in PFC. Our findings suggest a critical role of D1R/PKA/mTOR signaling cascade in the mPFC during thel -SPD mediated antidepressant process, which may also provide new insights into the role of mesocortical dopaminergic system in antidepressant effects.