Critique D'art, 47 | Automne \/ Hiver 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critique D'art, 53

Critique d’art Actualité internationale de la littérature critique sur l’art contemporain 53 | Automne/hiver CRITIQUE D'ART 53 The Landscape of African Art: Transformations at the Venice Biennale Dagara Dakin Translator: Phoebe Clarke Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/critiquedart/53747 DOI: 10.4000/critiquedart.53747 ISBN: 2265-9404 ISSN: 2265-9404 Publisher Groupement d'intérêt scientifique (GIS) Archives de la critique d’art Printed version Date of publication: 26 November 2019 Number of pages: 43-53 ISBN: 1246-8258 ISSN: 1246-8258 Electronic reference Dagara Dakin, « The Landscape of African Art: Transformations at the Venice Biennale », Critique d’art [Online], 53 | Automne/hiver, Online since 26 November 2020, connection on 01 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/critiquedart/53747 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/critiquedart.53747 This text was automatically generated on 1 December 2020. EN The Landscape of African Art: Transformations at the Venice Biennale 1 The Landscape of African Art: Transformations at the Venice Biennale Dagara Dakin Translation : Phoebe Clarke “Although I try and put things into perspective, I believe that the reason I have become so spiritually foreign to my native country, while remaining preoccupied by it – while it remains a preoccupation –, is for a great part its refusal to acknowledge the existence of this skull.”1 1 The Venice Biennale, to a greater extent than any other international event, offers a summary of the current global art scene, which could opportunely be re-questioned regarding the visibility of contemporary African art. Throughout the 1990s, the scant participation of African artists in the ritual art gathering was interpreted as the sign of the Western scene’s lack of open-mindedness. -

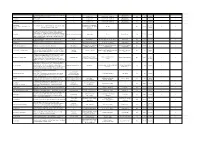

Bibliothèque Le Cube

titre de l'exposition artistes curateur auteurs lieu de l'exposition éditeurs nombre de pages année langue exposition d'artistes marocains nombre d'exemplaires Villa Delaporte / Fouad Bellamine, Mahi Binebine, Mustapha Boujemaoui, James Brown, Safâa Erruas, Sâad Hassani, Aziz Lazrak / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français x 1 art contemporains Villa Delaporte Après la pluie Pierre Gangloff / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 52p 2011 français 1 art contemporains Villa Delaporte Jacques Barry Angel For Ever / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français 1 art contemporains Yusur-Puentes espagnol - Paysage et architecture au Maroc et en Emilia Hernández Pezzi, Joaquín Ibáñez Montoya, Ainhoa Díez de Pablo, El Montacir Bensaïd, Iman Benkirane. Programmation culturelle de la Présidence espagnole de l’Union européenne Madrid 62p 2010 x 1 français Espagne Chourouk Hriech, Fouad Bellamine, Azzedine Baddou, Hassan Darsi, Ymane Fakhir, Faisal Samra, Fatiha Zemmouri, Mohamed Arejdal, Mohamed El Baz, Philippe Délis, Saad Tazi, Younes Baba Ali, Between Walls Abdelmalek Alaoui, Yasmina Naji Yasmina Naji Rabat Integral Editions 44p 2012 français x 1 Amande In, Anna Raimondo, Mohammed Fettaka, Ymane Fakhir, Mustapha Akrim, Hassan Ajjaj, Hassan Slaoui, Mohamed Laouli, Mounat Charrat, Tarik Oualalou, Fadila El Gadi Regards Nomades Mohamed Abdel Benyaich, Hassan Darsi, Mounir Fatmi, Younes Rahmoun, Batoul S'Himi Anne Dary Frédéric Bouglé Musée des Beaux Arts de Dole - France Ville de Dole 42p 1999 français -

Curators' Series #8 All of Us Have a Sense of Rhythm

CURATORS’ SERIES #8 ALL OF US HAVE A SENSE OF RHYTHM 05.06.2015 – 01.08.2015 INTRODUCTION It is a great pleasure to welcome eighth guest curator Christine Eyene and her ambitious and original exhibition All Of Us Have A Sense Of Rhythm to DRAF. This is, to my knowledge, the first exploration of the lineage of African rhythmic sources in modernist and contemporary practices, thanks to Eyene’s scholarship and personal dedication in its research. The exhibition encompasses sculpture, dance, poetry, video, performance, sound and music. It traces the cadences of modern masters (John Cage, Langston Hughes), popular subcultures (Northern Soul, drum’n’bass) and a contemporary generation of London African diaspora artists (Larry Achiampong, Evan Ifekoya). We look forward to welcoming visitors to this exciting show and concurrent programme of talks and live performances. DRAF is a factory for new prototypes to present and engage with art, and since 2009 exhibitions by international independent curators have introduced new forms to the space and our London audience. We have been particularly proud to present with them works of art from different continents, generations, practices and ideologies, many of which had never been previously displayed in the UK. The depth of their research, their individual curatorial sensibilities and the broad networks of artists and collaborators they have involved have made an invaluable contribution to our programme. Our guests have brought much to the household, and we have both enjoyed and learned from these collaborations. Our thanks to previous Curators’ Series participants, all of whom remain part of the family. -

• Joe ALFERS • Peter AUF DER HEYDE • Omar BADSHA • Rodger

• Joe ALFERS • Peter AUF DER HEYDE • Omar BADSHA • Rodger BOSCH • Julian COBBING • Gille DE VLIEG • Brett ELOFF • Don EDKINS • Ellen ELMENDORP • Graham GODDARD • Paul GRENDON • George HALLETT • Dave HARTMAN • Steven HILTON-BARBER • Mike HUTCHINGS • Lesley LAWSON • Chris LEDOCHOWSKI • John LIEBENBERG • Herbert MABUZA • Humphrey Phakade "Pax" MAGWAZA • Kentridge MATABATHA • Jimi MATTHEWS • Rafs MAYET • Vuyi Lesley MBALO • Peter MCKENZIE • Gideon MENDEL • Roger MEINTJES • Eric MILLER • Santu MOFOKENG • Deseni MOODLIAR (Soobben) • Mxolisi MOYO • Cedric NUNN • Billy PADDOCK • Myron PETERS • Biddy PARTRIDGE • Chris QWAZI • Jeevenundhan (Jeeva) RAJGOPAUL • Wendy SCHWEGMANN • Abdul SHARIFF • Cecil SOLS • Lloyd SPENCER • Guy TILLIM • Zubeida VALLIE • Paul WEINBERG • Graeme WILLIAMS • Gisele WULFSOHN • Anna ZIEMINSKI • Morris ZWI 1 AFRAPIX PHOTOGRAPHERS, BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES • Joe ALFERS Joe (Joseph) Alfers was born in 1949 in Umbumbulu in Kwazulu Natal, where his father was the Assistant Native Commissioner. He attended school and university in Pietermaritzburg, graduating from the then University of Natal with a BA.LLB in 1972. At University, he met one of the founders of Afrapix, Paul Weinberg, who was also studying law. In 1975 he joined a commercial studio in Pietermaritzburg, Eric’s Studio, as an apprentice photographer. In 1977 he joined The Natal Witness as a photographer/reporter, and in 1979 moved to the Rand Daily Mail as a photographer. In 1979, Alfers was offered a position as Photographer/Fieldworker at the National University of Lesotho on a research project, Analysis of Rock Art in Lesotho (ARAL) which made it possible for him to evade further military service. The ARAL Project ran for four years during which time Alfers developed a photographic recording system which resulted in a uniform collection of 35,000 Kodachrome slides of rock paintings, as well as 3,500 pages of detailed site reports and maps. -

Art. Contemporary. African

art. contemporary. Edition 1 Featuring: african. Odili Donald Odita, Otobong Nkanga, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Simon Njami, Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie, Riason Naidoo, Chimurenga. (Re-) Mapping the field: a bird’s eye view on discourses. IMPRINT / IMPRESSUM SAVVY | art.contemporary.african. SAVVY | kunst.zeitgenössisch.afrikanisch. Online magazine / Onlinezeitschrift Editor-in-chief / Project Initiator Chefredakteur / Projektinitiator Dr. Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung Deputy Editor-in-chief Stellv. Chefredakteurin Andrea Heister Editors of edition 1 Editoren von Ausgabe 1 Andrea Heister, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung Proofreading for edition 1 Lektorat von Ausgabe 1 Katja Vobiller, Simone Kraft, Andrea Heister, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung Authors of edition 1 Autoren von Ausgabe 1 Aicha Diallo, Brenda Cooper, Andrea Heister, Prune Helfter, Nancy Hoffmann, Missla Libsekal, Alanna Lockward, Riason Naidoo, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Simon Njami, Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie, Annette Schemmel, Fiona Siegenthaler, Kangsen Feka Wakai Translations Übersetzungen Katja Vobiller, Claudia Lamas Cornejo, Johanna Ndikung, Simone Kraft, Andrea Heister Web design Webdesign Alice Motanga Graphic design Grafikdesign Soavina Ramaroson Bureau Büro Richardstr. 43/44 12055 Berlin Germany 3 TABLE OF CONTENT 0. Editorial Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung 1. Spotlight on... Go tell it on the mountain Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung / Andrea Heister A Maestro kicks the bucket: an obituary on Malangatana Der Vorhang fällt: ein Nachruf auf Malangatana Andrea Heister Wangechi Mutu passes the courvoisier to Yto Barrada Wangechi Mutu reicht den Courvoisier an Yto Barrada Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung House of African Art: First African Art Space in Asia House of African Art: erstes Haus für afrikanische Kunst in Asien Prune Helfter Goddy Leye is dead Goddy Leye ist tot Annette Schemmel 2. -

Third Text Reviews

This article was downloaded by: [90.197.75.198] On: 02 December 2014, At: 12:48 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Third Text Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ctte20 Reviews Anthony Downey , Christine Eyene , Amna Malik , Lize van Robbroeck , Theresa Avila & Alyssa Grossman Published online: 10 Feb 2009. To cite this article: Anthony Downey , Christine Eyene , Amna Malik , Lize van Robbroeck , Theresa Avila & Alyssa Grossman (2008) Reviews, Third Text, 22:6, 787-803, DOI: 10.1080/09528820802652573 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09528820802652573 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Creative Conversations: Black Women Artists Making & Doing Influences

Creative Conversations: Black Women Artists Making & Doing Influences and Inspirations of Literature and Language on Black Women’s Creativity Lubaina Himid, Five (from the Revenge series), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, 60 ins x 48 ins Image courtesy the artist and Griselda Pollock. On permanent loan/display at Leeds Art Gallery University of Central Lancashire, 16-17 January 2020 1 Two-day Symposium at UCLAN, 16-17 January 2020. Organised in celebration of the many achievements of Prof. Lubaina Himid, CBE, RA. 35 years of art making, curating and creating conversations, and the first black woman to win the Turner Prize (2017). 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS These events have been sponsored by the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan), the Institute for Black Atlantic Research (IBAR), the UCLan Research Centre for Migration, Diaspora and Exile (MIDEX), the Making Histories Visible Archive (MHV), and UCLan’s School of Humanities, Language & Global Studies and Faculty of Culture and Creative Industries. MHV MIDEX 3 DAY ONE: THURSDAY 16TH JANUARY 11.00am - 17.30pm Media Factory ME 414 11.00 - 11.30 - Registration (refreshments provided) 11.30 - 11.40 - Welcome Address by Prof. Alan Rice 11.40 - 13.15 - Panel One (Chair: Dr Ella S. Mills) • Prof. Lubaina Himid: Maupassant to May Sarton via Essex Hemphill and Toni Cade Bambara: Navigating Madness, Activating Change through painting and reading • Christine Eyene: Making Histories Visible: the George Hallett project • Marlene Smith: Bad Housekeeping: key works, key texts 13.15 - 14.15 - Lunch (provided) in -

Gideon Mendel Release FINAL

The outskirts of Yenagoa, Bayelsa State, Nigeria November 2012 Gideon Mendel: Drowning World Preview: Thursday, 6 June 2013 | 6:30 – 8:30pm On View: Friday, 7 June – Saturday, 27 July 2013 Tiwani Contemporary presents Drowning World an exhibition by South African photographer Gideon Mendel, curated by Christine Eyene. The selection includes 15 images taken in Nigeria that have never been exhibited, and 5 photographs documenting flooding in various parts of the globe including England, India, Haiti and Australia. The exhibition also presents a two-part video of people living amidst floodwaters in Bangkok, as well as video portraits of Nigerian inhabitants returning to their flooded homes. Drowning World is a poignant depiction of climate change through portraits of flood survivors taken in deep floodwaters, within the remains of their homes, or in submerged landscapes, in the stillness of once lively environments. Keeping their composure, the subjects pause in front of Mendel’s camera, casting an unsettling, yet engaging gaZe. These images, taken across the globe demonstrate a shared experience that erases geographical and cultural divides. They invite the viewer to reflect on the impact on nature by humankind, and attachment to our homes and personal belongings. Beyond the documentary aspect of this project, Gideon Mendel subtly treads on the aesthetics of portraiture, yet pushes the boundaries by staging the photographs in unlikely environments. Each portrait isolates individuals, couples or small groups that would otherwise be represented by statistics. The portraits also reveal personality and status through clothes, style and even elegance. As well as representing destruction, water also contributes to the creative process. -

Bibliothèque Le Cube.Xlsx

titre de l'exposition artistes curateurs auteurs lieu de l'exposition éditeurs nombre de pages année langue exposition d'artistes marocains nombre d'exemplaires Fouad Bellamine, Mahi Binebine, Mustapha Boujemaoui, James Brown, Villa Delaporte / / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français x 1 Safâa Erruas, Sâad Hassani, Aziz Lazrak art contemporains Villa Delaporte Après la pluie Pierre Gangloff / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 52p 2011 français 1 art contemporains Villa Delaporte Jacques Barry Angel For Ever / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français 1 art contemporains Yusur-Puentes Programmation culturelle de la Emilia Hernández Pezzi, Joaquín Ibáñez Montoya, Ainhoa Díez de Pablo, espagnol - Paysage et architecture au Maroc et en Présidence espagnole de l’Union Madrid 62p 2010 x 1 El Montacir Bensaïd, Iman Benkirane. français Espagne européenne Chourouk Hriech, Fouad Bellamine, Azzedine Baddou, Hassan Darsi, Ymane Fakhir, Faisal Samra, Fatiha Zemmouri, Mohamed Arejdal, Mohamed El Baz, Philippe Délis, Saad Tazi, Younes Baba Ali, Amande In, Between Walls Abdelmalek Alaoui, Yasmina Naji Yasmina Naji Rabat Integral Editions 44p 2012 français x 1 Anna Raimondo, Mohammed Fettaka, Ymane Fakhir, Mustapha Akrim, Hassan Ajjaj, Hassan Slaoui, Mohamed Laouli, Mounat Charrat, Tarik Oualalou, Fadila El Gadi Mohamed Abdel Benyaich, Hassan Darsi, Mounir Fatmi, Younes Regards Nomades Anne Dary Frédéric Bouglé Musée des Beaux Arts de Dole - France Ville de Dole 42p 1999 français x 1 Rahmoun, Batoul -

George Hallett: Nomad, Raconteur and Photographer Who 'Became The

George Hallett: Nomad, raconteur and photographer who ‘became the camera’ M Neelika Jayawardane 8 July 2020 Recreating memory: Dancers, 1967. (George Hallett) Anyone who met George Hallett, the South African photographer who passed away on July 1, at the age of 77, knows he was a born performer and raconteur, who relished the spotlight at any gathering. Yet, he was also a trickster figure — a chameleon who knew how to blend in with the background, and observe his photographic subjects‟ burdens and most vulnerable states. Hallett‟s iconic portraits reveal his shaman‟s ability — his ceremonial performances with the camera that created openings into his subjects, especially those who had a lot to hide. One would not necessarily realise that the slim, lanky man with a small camera, standing unobtrusively in a crowd, had taken photographs that broke through the reserve of seasoned charmers and politicians — including Nelson Mandela — and those, like Eugene de Kock, who had been responsible for the torture and deaths of hundreds, if not thousands, of South Africans who fought for freedom. Hallett was notoriously economical with his film — times were tough, and film expensive — taking only one or two frames. Yet each portrait that Hallett took is extraordinary — be they of those history has now marked as villain or hero; or the countless South African exiles in Europe with whom he forged close bonds, and whose loneliness, hardships and pain were invisible to a larger public. Perhaps, as a man who used performance and a loud persona to mask his own difficult experiences of exclusion, and maintained the effects of that damage behind tall tales of grand exploits, he knew how to read beyond what others, too, projected onto the screen. -

Nirveda Alleck

NIRVEDA ALLECK Born in Mauritius, 1975 Lives in Mauritius ART EDUCATION 2001 Master of Fine Art (MFA), Glasgow School of Art, Scotland 1997 Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts (Hons.), First Class, University of Cape Town, SA Placed on the Dean’s Merit List SPECIAL MENTIONS 2016 Honored to be listed among the 100 most Influencial women of Mauritius President of Jury for Prix Celimene, Department of Sports and Culture, Reunion Island. 2012-2015 Chair of Arterial Network Mauritius Chapter 2012 Cultural Leadership Training, at the African Arts Institute of South Africa, EU/AFAI funded. Recipient of Emma Award by Bank One, for Arts and Culture, Mauritius. 2011 Nominated for FNB Art Prize at Joburg Art Fair Nominated For One Minutes Africa 2011, Townhouse Gallery, Cairo Francis J Greenburger Fellowship at Omi International Arts Centre, USA Recipient of International Grant for Artist Scheme, Ministry of Arts and Culture Mauritius 2010 Laureate at Dakar Biennale 2010, Soleil d’Afrique Prize 2008 Sponsored by HIVOS to take part in Tulipamwe International Artists Workshop and Exhibition Namibia 2004 Selected for ‘ 1er Fond D’Aide au Développement du Film’, Mauritius Film Development Corporation 1999 School of Fine Art Postgraduate Scholarship, Glasgow School of Art 1998 Most Promising Young Artist Award, Seychelles Biennial of Contemporary Art 1997 Dean’s Merit List, University of Cape Town 1994 Edward Louis Ladan Bursary offered by the University of Cape Town PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2016-Now Lecturer in Fine Arts, Mahatma Gandhi Institute, Mauritius -

Yamamotokeikorochaix Instagram: Instagram.Com/Yamamotokeikorochaix Website

Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix PRESS RELEASE Still unresolved and very much ongoing 9th June ‒ 5th August 2017 Private view and opening reception: 8th June 2017, 6pm Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix is pleased to present 'Still unresolved and very much ongoing', a selection of works by Delaine Le Bas (UK), Thierry Geoffroy (France/ Denmark), Elsa M’bala (Cameroon/Germany), Gideon Mendel (South Africa/UK), and texts from Bakwa Magazine and its editor Dzekashu MacViban (Cameroon). Curated by Christine Eyene, the exhibition takes on the rhetoric of the importance of art ‘now more than ever’ ‒ a discourse that gained currency on social media in the face of the crisis of humanism ‒ to examine the relationship between the socio- political and aesthetics. Drawing from the British context as point of departure, the wave of exhibitions by Black British artists demonstrating the recurrence of the issues they addressed in the 1980s, and the continued relevance of their art to this day, this project is the result of ongoing conversations with artists who have always been alert to the fragility of democracies and concerned with the pockets of exclusions that exist in the so-called ‘Free World’. “Still unresolved and very much ongoing” is a quote from an essay by British art historian Kobena Mercer entitled “Iconography after Identity” (2005) in which he discusses Black British Art and the importance and complexities of apprehending identity-based, and by extension socio-politically oriented art, through the prism of iconography and iconology. The exhibition title also reflects the current climate of surreal revival of past forms of prejudice and injustice thought to be eradicated but resurfacing like a societal necrosis.