Relfections on Die Andere Heimat, October 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Home Chronicle of a Vision

HOME FROM HOME CHRONICLE OF A VISION A FILM BY EDGAR REITZ Set in a dreary, unforgiving mid-19th century German village in Hunsrück, Home From Home captures the plight of hundreds of thousands of Europeans who emigrated to faraway South America to escape the famine, poverty and despotism that ruled at home. Their motto was: “Any fate is better than death”. Edgar Reitz’s film is a heart-wrenching drama and love story set against the backdrop of this forgotten tragedy. It encompasses a time of tribulation and illuminates the revolutionary and intellectual spirit present in the souls who are center of this tale. Jakob, our protagonist, tries to immerse himself in literature and learning, as the rest of his family toils to fend off starvation. He dreams about leaving his village, Schabbach, for a new life in Brazil and the freedom of the wild South American jungle. Jakob’s brother, Gustav, returns from military service and his appearance is destined to shatter Jakob’s world and his love for Henriette, as it symbolizes the necessary rift that will set into motion the unraveling of the regimented family structure. 2013 | Germany | 230 min | German w/English Subtitles | B&W | Historical Fiction CORINTH FILMS PRESENTS AN ERF EDGAR REITZ FILMPRODUCTION MUNICH IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH LES FILMS DU LOSANGE PARIS AND ARD DEGETO BR WDR ARTE WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF CENTRE NATIONAL DE CINEMA ET DE L’IMAGE ANIMEE ARTE FRANCE CINE+ STARRING JAN DIETER SCHNEIDER ANTONIA BILL MAXIMILIAN SCHEIDT MARITA BREUER RÜDIGER KRIESE PHILINE LEMBECK AND MÉLANIE FOUCHÉ PRODUCED BY CHRISTIAN REITZ CO-PRODUCED BY MARGARET MENEGOZ SCREENWRITERS EDGAR REITZ GERT HEIDENREICH CINEMATOGRAPHY GERNOT ROLL PRODUCTION DESIGN TONI GERG† HUCKY HORBERGER COSTUME DESIGN ESTHER AMUSER MAKE UP ARTIST NICOLE STOEWESAND SOUND DESIGNER MARC PARISOTTO PHILIPPE WELSH EDITOR UWE KLIMMECK ORIGINAL MUSIC BY MICHAEL RIESSLER DIRECTED BY EDGAR REITZ German filmmaker, author and producer, Edgar Reitz grew up in the Hunsrück region, studied German language and literature, journalism and dramatics in Munich. -

1848 Reitz-Flyer a 6 V.3.3.Indd

EDGAR REITZ Die große Werkschau 5.1. – 4.3.2018 filmhaus.nuernberg.de EDGAR REITZ Die große Werkschau Edgar Reitz ist einer der bedeutendsten deutschen DIE ZWEITE HEIMAT, ein Rückblick in die bewegten Die ZuschauerInnen können sich aus einer „Film- Filmregisseure. Diesem großen Meister der Erzähl- 60er- und 70er Jahre, und HEIMAT 3, die die jüngste Speisekarte“ das Programm selbst zusammenstellen. kunst widmet das Filmhaus nun eine umfassende Episode deutscher Geschichte mit dem Mauerfall Werkschau, mit der erstmals nahezu das komplette und der Immigration von Ost nach West themati- Die Werkschau wird mit Diskussionen, Live Music filmische Schaffen des Regisseurs in einer Retro- siert. 2012 realisierte Reitz dann den großen Kino- Acts und Vorträgen begleitet, Edgar Reitz wird viele spektive zusammengefasst und in neuen restaurier- film DIE ANDERE HEIMAT über die Auswanderung Programmpunkte selbst vorstellen und für Gesprä- ten und digitalisierten Fassungen präsentiert wird. der Hunsrücker nach Brasilien im 19. Jahrhundert. che mit dem Publikum zur Verfügung stehen. Da- rüber hinaus freuen wir uns auf weitere Gäste, wie Mit seiner international gefeierten HEIMAT-Saga Edgar Reitz’ Werk umfasst mehr als 40 Dokumen- die Regisseurin Ula Stöckl, die SchauspielerInnen hat Edgar Reitz ein filmisches Epos geschaffen, tar- und Spielfilme, darunter MAHLZEITEN, der Hannelore Elsner, Hannelore Hoger, Tilo Prückner, das seinesgleichen sucht. Er hat damit nicht nur 1967 als bestes Erstlingswerk auf den Filmfest- Henry Arnold, Marita Breuer, Salome Kammer, Armin Filmgeschichte geschrieben, sondern gehört auch spielen in Venedig ausgezeichnet wurde, DIE REISE Fuchs und den Filmwissenschaftler Prof. Dr. Thomas zu den großen Erzählern deutscher Geschichte NACH WIEN (1973), STUNDE NULL (1977) und DER Koerber, Robert Fischer und viele andere. -

FILMHAUS 1/18 Königstraße 93 · 90402 Nürnberg filmhaus.Nuernberg.De · T: 2317340 REITZ

FILMHAUS 1/18 Königstraße 93 · 90402 Nürnberg filmhaus.nuernberg.de · T: 2317340 REITZ DGAR E EDGAR REITZ – DIE GROSSE WERKSCHAU Edgar Reitz ist einer der bedeutendsten deutschen Sein Werk umfasst mehr als 40 Dokumentar- und Die große Werkschau bietet Wie soll man leben? Wie soll man lieben? In Filmregisseure. Diesem großen Meister der Erzählkunst Spielfilme, darunter MAHLZEITEN, der 1967 als bestes die Gelegenheit, die Filme von Edgar Reitz zu widmet das Filmhaus nun eine umfassende Werkschau, Erstlingswerk auf den Filmfestspielen in Venedig aus- erleben und (wieder) zu entdecken. Darunter befind- den Filmen des koreanischen Regisseurs Hong mit der erstmals nahezu das komplette filmische Schaffen gezeichnet wurde, DIE REISE NACH WIEN (1973), en sich Schätze wie frühe Kurzfilme oder die frechen geht es in gänzlich unspektakulärer des Regisseurs in einer Retrospektive zusammengefasst STUNDE NULL (1977) und DER SCHNEIDER VON ULM GESCHICHTEN VOM KÜBELKIND (1971/2017), die Weise immer ums Ganze. So auch in seinem und in neuen restaurierten und digitalisierten Fassungen (1978). Edgar Reitz war Unterzeichner des Oberhausener Anfang März wie damals als Kneipenkino vorgeführt neuesten Werk. Mit präsentiert wird. Manifests von 1962, ein wegbereitendes Ereignis in der werden: Die Zuschauer können sich aus einer „Film- scher Schlichtheit und feinem Humor nä- Mit seinen international gefeierten HEIMAT-Chroniken bundesdeutschen Filmgeschichte. Junge Filmschaffende Speisekarte“ das Programm selbst zusammenstellen. hert sich ON THE BEACH AT NIGHT ALONE – so hat Edgar Reitz ein filmisches Epos geschaffen, das sei- proklamierten: „Papas Kino ist tot“ und forderten ein Die große Werkschau wird mit Diskussionen und heißt übrigens auch eines der kosmischsten Ge- nesgleichen sucht. Er hat damit nicht nur Filmgeschichte neues, selbständiges und von der Förderung nicht ge- Vorträgen begleitet, Edgar Reitz wird viele Pro- dichte Walt Whitmans –, dem von Melancholie geschrieben, sondern gehört auch zu den großen Erzäh- gängeltes Kino. -

THE GERMAN SOCIETY of PENNSYLVANIA Die Andere Heimat

surplus of misery at home, yet most of them do not know this. Jakob Simon, ein Hunsrücker Bauernjunge who reads books and has “Das Paradies im Kopf” keeps a diary and is the con- THE GERMAN SOCIETY OF duit of Sehnsucht to his family and friends in the village. He sees families continually leav- ing the village and the surrounding area, and wonders why, given the pain of parting and the PENNSYLVANIA dangers of the journey, so many are leaving. When migrants leave, they pass over a stout stone bridge and the women washing clothes Friday Film Fest Series below watch them trundle over the bridge, heading toward their own future as they simulta- neously become part of Schabach’s past. Jakob soon learns why these villagers are leaving: they are going to Brazil at the invitation of the Portuguese Emperor. He spends as much time as he can steal away from work reading books about the flora, fauna and people of Bra- zil. One day, when the time is right, he will go there, to the land where the sun goes when it departs from Schabach. Jakob’s horizons are very circumscribed, as are those of all the denizens of Schabach, but the world within those horizons is known and can be counted on to continue as it has always been, misery and mud and melancholy notwithstanding. There is comfort in knowing this, however slight: “…Etwas Besseres als den Tod …” The harsh class hierarchy of that time intrudes when Jakob is imprisoned following a fracas during a harvest fest, while his brother Gustav gets the only girl in the village who seemed to understand Jakob in a family way. -

GARDENS of COOPERATION Alexander Kluge

Alexander Kluge GARDENS OF COOPERATION Alexander Kluge (Halberstadt, 1932) has had an astonishingly multifaceted career. With fifty-five short and feature films, almost three thousand television programmes, a vast literary oeuvre and highly influen- tial essays on political theory and film history under his belt, Kluge has outgrown the epithet of cult creator to become a kind of multi-limbed institution. 05.11.2016 – 05.02.2017 © Archiv der Internationalen Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen Gardens of Cooperation is the first exhibition on Alex- ander Kluge in Spain and the only museum retrospec- tive to date to cover his entire oeuvre in an international context. Alexander Kluge has overseen the show himself and provided a large amount of previously unseen mate- rials, from both his personal archives and the documen- tary resources of his production company, Kairos-Film. All the audiovisual compilations on display have been specifically created by Alexander Kluge for La Virreina Centre de la Imatge. Along with this, in the context of Gardens of Coop- eration, nine new short films are being premiered. These include Herbert Hausdorf: Brother of my Mother, The Opera Principle, Digital Night Sky over Paris on November 13, 2015: Dark and Mute, Time to Live Against Money, Ingeborg Bachmann: Homage to Maria Callas, Anatomy of a Centaur (According to Leonardo da Vinci), Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Triptychon and The Intestine Thinks. Alexander Kluge (Halberstadt, 1932) has had an astonish- ingly multifaceted career. With fifty-five short and feature films, almost three thousand television programmes, a vast literary oeuvre and highly influential essays on political theory and film history under his belt, he has outgrown the epithet of cult creator to become a kind of multi-limbed institution. -

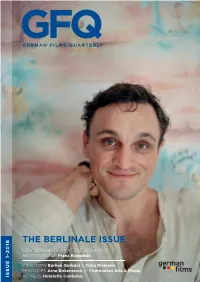

The Berlinale Issue

GFQ GERMAN FILMS QUARTERLY THE BERLINALE ISSUE NEW GERMAN FILMS AT THE BERLINALE SHOOTING STAR Franz Rogowski DIRECTORS Burhan Qurbani & Ziska Riemann PRODUCER Arne Birkenstock of Fruitmarket Arts & Media ISSUE 1-2018 ACTRESS Henriette Confurius CONTENTS GFQ 1-2018 4 5 6 7 8 10 13 16 32 35 36 49 2 GFQ 1-2018 CONTENTS IN THIS ISSUE IN BERLIN NEW DOCUMENTARIES 3 TAGE IN QUIBERON 3 DAYS IN QUIBERON Emily Atef ................. 4 ABHISHEK UND DIE HEIRAT ABHISHEK AND THE MARRIAGE Kordula Hildebrandt .................. 43 IN DEN GÄNGEN IN THE AISLES Thomas Stuber ............................ 5 CLIMATE WARRIORS Carl-A. Fechner, Nicolai Niemann ............... 43 MEIN BRUDER HEISST ROBERT UND IST EIN IDIOT MY BROTHER’S NAME IS ROBERT AND HE IS AN IDIOT Philip Gröning .................... 6 EINGEIMPFT FAMILY SHOTS David Sieveking ................................. 44 TRANSIT Christian Petzold ................................................................ 7 FAREWELL YELLOW SEA Marita Stocker ....................................... 44 DAS SCHWEIGENDE KLASSENZIMMER GLOBAL FAMILY Melanie Andernach, Andreas Köhler .................. 45 THE SILENT REVOLUTION Lars Kraume ......................................... 8 JOMI – LAUTLOS, ABER NICHT SPRACHLOS STYX Wolfgang Fischer ...................................................................... 9 JOMI’S SPHERE OF ACTION Sebastian Voltmer ............................. 45 DER FILM VERLÄSST DAS KINO – VOM KÜBELKIND-EXPERIMENT KINDSEIN – ICH SEHE WAS, WAS DU NICHT SIEHST! UND ANDEREN UTOPIEN FILM BEYOND CINEMA -

Our Hunsrück Expedition

Our Hunsrück expedition Explanation of pictures taken on from 29th of August until 5th of September 2010. IMG_1132 ‐ Same evening of our arrival in Hunsrück we make our first stroll in the surroundings of Sulzbach (south of Rhaunen) IMG_1133 ‐> 1141 – Wandering around in the neighborhood of Sulzbach and Rhaunen IMG_1142 ‐> 1148 – Checking out Woppenroth the most important part of the multipart (and therefore ) not really existing but constructed mythical village of Schabbach. IMG_1150 ‐> 1164 – Another part of mythical Schabbach: Gehlweiler with the forge / Schmiede „Simon“ IMG_1166 ‐> 1176 ‐ Of course we needed to hike around in beautiful Hunsrück as well, and rest too. People (Celts and Romans) resided here already a long time (since the second century ) IMG_1177 ‐> 1180 ‐ Not going anywhere without my morning coffee. IMG_1181 ‐> 1205 ‐ Mediaeval Herrstein has a “Traumschleife“ / Dreamtrail with wonderful sights and offered Marian the opportunity to tie me to a pillory and lead us along a cemetery into the fields with a place to lounge. IMG_1206 ‐> 1227 ‐ Our excursion to local capital Simmern with a Heimat department in the the local Hunsrücker museum with props and pictures from the series 1 and 3. And a picture of Marian’s favorite character Marie Goot, together with director Edgar Reitz. IMG_1235 ‐> 1238 – Nearby Kirchberg, a typical quiet Hunsrücker town. IMG_1239 ‐> 1256 ‐ Expedition to the slate mines of Budenbach where some scenes were taken of Heimat 3 and the focus point of the Robin Hood like Schinderhannes saga. IMG_1257 ‐> 1276 ‐ Jewels centre Idar‐Oberstein is a nice intermission on our expedition from Schneppenbach to the “Teufel Fels” / Devils Rock. -

Pressemitteilung München, 27. Mai 2019 AUFBRUCH INS JETZT – Der

Pressemitteilung München, 27. Mai 2019 AUFBRUCH INS JETZT – Der Neue Deutsche Film 6.6 – 28.7.2019, Bayerische Akademie der Schönen Künste, München mit einem filmischen Begleitprogramm im Filmmuseum München und im Theatiner Am 6. Juni 2019 eröffnet die Bayerische Akademie der Schönen Künste in München die multimediale Ausstellung „AUFBRUCH INS JETZT – Der Neue Deutsche Film“ des Schweizer Fotografen Beat Presser und ermöglicht einen frischen Blick zurück nach vorn in Bild, Wort und Ton auf die zeit- und filmhistorisch bedeutsame Ära des Neuen Deutschen Films. „Der alte Film ist tot. Wir glauben an den neuen.“, hieß es im Oberhausener Manifest vom 28. Februar 1962. Welche Folgen hatte der damalige Aufbruch für den Film in der Bundesrepublik? Beat Presser, Standfotograf für Werner Herzog bei Fitzcarraldo, Cobra Verde und Invincible, hat in den vergangenen neun Jahren 56 Personen aller filmischen Gewerke fotografiert, befragt und gefilmt, die an Produktionen des Neuen Deutschen Films vor oder hinter der Kamera beteiligt waren. Sie haben auf unterschiedliche Weise zu Erneuerung beigetragen. Einige von ihnen sind vielfach ausgezeichnet worden, andere wirkten eher im Hintergrund. Der immer wieder überraschende Blick zurück nach vorn wird erlebbar anhand rund 150 schwarz-weiß und farbiger zeitgenössischer fotografischer Portraits. Video- und Soundinstallationen ermöglichen einen Einblick aus heutiger Sicht auf den Aufbruch von damals. Zur Ausstellung erscheint die Publikation „AUFBRUCH INS JETZT – Der Neue Deutsche Film. Gespräche – Beat Presser“ -

Die Lange Nacht Mit Dem Filmemacher Edgar Reitz

„Eine gute Geschichte ist nie ganz erklärbar“ Die Lange Nacht mit dem Filmemacher Edgar Reitz Autorin: Beate Becker Regie: die Autorin Redaktion: Dr. Monika Künzel SprecherIn Ruth Reinecke (Sprecherin) Christian Schmidt (Sprecher) Cornelia Schönwald (Bilderzählerin) Thomas Fränzel (Zitator) Sendetermine: 2. November 2019 Deutschlandfunk Kultur 2./3. November 2019 Deutschlandfunk ___________________________________________________________________________ Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis: Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Jede Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in den §§ 45 bis 63 Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig. © Deutschlandradio - unkorrigiertes Exemplar - insofern zutreffend. 1. Stunde MUSIK: Hussong: Whose Song. John Cage, Souvenir Sprecherin: Edgar Reitz ist einer der großen zeitgenössischen deutschen Filmemacher. Er wurde 1932 geboren und wuchs im Hunsrücker Dorf Morbach auf. Nach dem Abitur, ging er nach München, wo er heute noch lebt. International bekannt wurde Edgar Reitz ab den 80er Jahren durch die Trilogie mit dem Titel „Heimat“, die mehr als 50 Stunden umfasst und an der er über 30 Jahre arbeitete. In der ersten Stunde der Langen Nacht spricht Edgar Reitz über seine Herkunft und dem „Sich-in-die Fremde träumen“. Er beschreibt seine Anfänge als experimenteller Kurzfilmer in München in den 50er Jahre und erste Begegnungen mit der Neuen Musik, spricht über das „Oberhausener Manifest“ und den großen Erfolg mit seinem ersten Spielfilm „Mahlzeiten“ 1967 auf der Biennale in Venedig. Zwischen 1968-78 hat er „Cardillac“, „Reise nach Wien“, „Schneider von Ulm“ und die „Stunde Null“ gedreht. Wichtige Filme, die weniger erfolgreich waren als die „Heimat-Chroniken“, die im Zentrum der zweiten Stunde stehen sollen. -

Der Schneider Von Ulm Die Andere Heimat Die Nacht Der Regisseure

DIE ANDERE HEIMAT HEIMAT - EINE DEUTSCHE CHRONIK Der Schneider von Ulm Die Nacht der Regisseure DE 1978, 121 Min., FSK ab 12 Jahren, Regie: Edgar Reitz, Drehbuch: Edgar DE 1995, 87 Min., FSK ab 12 Jahren, Regie: Edgar Reitz, Drehbuch: Edgar Reitz Reitz, Petra Kiener, Besetzung: Tilo Prückner, Vadim Glowna, Hannelore Els- Besetzung: Volker Schlöndorff, Helma Sanders-Brahms, Margarethe von Trotta, ner, Harald Kuhlmann, Kamera: Dietrich Lohmann Wolfgang Kohlhaase, Frank Beyer, Hans Jürgen Syberberg, Peter Schamoni, Alex- ander Kluge, Peter Fleischmann, Leni Riefenstahl, Wim Wenders, Werner Herzog, Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts: Albrecht Berblinger, Schneider- Wolfgang Becker geselle, ist zu Fuß unterwegs von Wien nach Ulm, seiner Hei- matstadt. In seinem Gepäck ein ausgestopfter Bussard, in Dokumentarfilm mit Spielszenen und digitaler Animation. Teil einer seinem Kopf ein schwindelerregender Traum: Der Traum vom Filmreihe zum 100.Geburtstag des Kinos. Menschenflug, von vogelgleichen Reisen durch die Luft. So widmet er sich in seiner Freizeit fortan Versuchen, ein funk- tionstüchtiges Fluggerät herzustellen. Schließlich soll er vor Geschichten vom Kübelkind dem Stuttgarter König seine Künste mit einer Überquerung DE 1971, 90 Min., FSK ab 18 Jahren, Regie: Ula Stöckl, Edgar Reitz der Donau unter Beweis stellen. Drehbuch: Edgar Reitz, Besetzung: Kristine de Loup, Heidewig Fankhänel, Erika Heffner Die andere Heimat Kurzfilmprogramm mit der Kunstfigur Kübelkind, das vom bürgerlichen Problemfilm, über den Gangsterfilm und Historienfilm, in den Western DE 2013, 231 Min., FSK ab 6 Jahren, Regie: Edgar Reitz und ins Musical stolpert. Drehbuch: Edgar Reitz, Gert Heidenreich, Besetzung: Werner Herzog, Im Jahr 1969 schüttete eine Krankenschwester eine Nachgeburt aus Antonia Bill, Jan Dieter Schneider u. -

9 Historicising the Story Through Film and Music

9 Historicising the Story through Film and Music An Intermedial Reading of Heimat 21 Abstract Chapter 9 focuses on Heimat 2: Chronicle of a Generation (Die zweite Heimat: Chronik einer Jugend, 1992), the second part of the monumental Heimat TV and cinema series, scripted and directed by German filmmaker Edgar Reitz. The project, spanning over 60 hours, has in Heimat 2 its longest instalment, with 13 episodes totalling more than 25 hours of film. My objective here is to evaluate the ways in which the Heimat 2 series, as part of a ‘total-history’ project, i.e. the retelling of the history of Germany from the nineteenth century to today, presents history in the making by means of intermediality, that is, through the use of music as theme, diegetic performance and organisational principle of all episodes. Keywords: Heimat series; Edgar Reitz; German Cinema; New German Cinema; New Music; Intermediality This chapter focuses on Heimat 2: Chronicle of a Generation (Die zweite Heimat: Chronik einer Jugend, 1992), the second part of the monumental Heimat TV and cinema series, which started with Heimat: A Chronicle of Germany (Heimat: eine deutsche Chronik, 1982) and continued with Heimat 3: A Chronicle of Endings and Beginnings (Heimat 3: Chronik einer Zeitenwende, 2004) and Home from Home: A Chronicle of Vision (Die andere Heimat: Chronik einer Sehnsucht, 2013), all scripted and directed by German filmmaker Edgar Reitz. The project, spanning over 60 hours so far, has in Heimat 2 its longest instalment, with 13 episodes totalling more than 25 hours of film. 1 I would like to thank Suzana Reck Miranda and John Gibbs for their technical advice on this chapter. -

Br-Alpha Forum. Interview with Edgar Reitz by Walter Greifenstein

br-alpha Forum interview with Edgar Reitz, Page 1 of 10 Professor Edgar Reitz Film Director interviewed by Walter Greifenstein. Broadcast on br-alpha, January 13th 2007, first broadcast on January 3rd 2005. Original German at http://www.br-online.de/alpha/forum/vor0701/20070113_i.shtml. Amateur translation by Angela Skrimshire with helpful suggestions from Thomas Hönemann, published on www.heimat123.de. Greifenstein: Welcome to the BR-Alpha Forum. Our guest today is the author and film director, Edgar Reitz, one of the co-founders of the New German Film in the sixties, and author of a hitherto unique body of artistic work: 54 hours of film devoted to one theme, namely that of Heimat. A warm welcome to you, Herr Reitz. Reitz: Grüß Gott. Greifenstein: I am happy that you have found the time to come here. A frank question: doesn’t it sometimes annoy you that your name has become almost synonymous with the concept of “Heimat”, is it annoying to be associated only with that? Reitz: Of course that’s the title. I gave the whole thing the broad label “Hei- mat” but it is certainly no documentary film, and also not a thematic film, de- voted only to a single defined issue, but it is a narrative: it is like the material of a novel, and is about many things and not just about Heimat. And therefore through all these years it was in no way a one-sided preoccupation, but it was truly a mirror image of life for me. Also, it was not as though 25 years ago I already knew how the whole thing was to end.