Book of Abstracts (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programme 2009 the Abel Prize Ceremony 19 May 2009 Procession Accompanied by the “Abel Fanfare” Music: Klaus Sandvik

Programme 2009 The Abel Prize Ceremony 19 May 2009 Procession accompanied by the “Abel Fanfare” Music: Klaus Sandvik. Performed by three musicians from the Staff Band of the Norwegian Defence Forces Their Majesties King Harald and Queen Sonja enter the hall Soroban Arve Henriksen (trumpet) (Music: Arve Henriksen) Opening by Øyvind Østerud President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters Eg veit i himmerik ei borg Trio Mediæval, Arve Henriksen (Norwegian folk tune from Hallingdal, arr. Linn A. Fuglseth) The Abel Prize Award Ceremony Professor Kristian Seip Chairman of the Abel Committee The Committee’s citation His Majesty King Harald presents the Abel Prize to Mikhail Leonidovich Gromov Acceptance speech by Mikhail Leonidovich Gromov Closing remarks by Professor Øyvind Østerud President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters Till, till Tove Trio Mediæval, Arve Henriksen, Birger Mistereggen (percussion) (Norwegian folk tune from Vestfold, arr. Tone Krohn) Their Majesties King Harald and Queen Sonja leave the hall Procession leaves the hall Other guests leave the hall when the procession has left to a skilled mathematics teacher in the upper secondary school is called after Abel’s own Professor Øyvind Østerud teacher, Bernt Michael Holmboe. There is every reason to remember Holmboe, who was President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters Abel’s mathematics teacher at Christiania Cathedral School from when Abel was 16. Holmboe discovered Abel’s talent, inspired him, encouraged him, and took the young pupil considerably further than the curriculum demanded. He pointed him to the professional literature, helped Your Majesties, Excellencies, dear friends, him with overseas contacts and stipends and became a lifelong colleague and friend. -

Oslo 2004: the Abel Prize Celebrations

NEWS OsloOslo 2004:2004: TheThe AbelAbel PrizePrize celebrationscelebrations Nils Voje Johansen and Yngvar Reichelt (Oslo, Norway) On 25 March, the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters announced that the Abel Prize for 2004 was to be awarded to Sir Michael F. Atiyah of the University of Edinburgh and Isadore M. Singer of MIT. This is the second Abel Prize awarded following the Norwegian Government’s decision in 2001 to allocate NOK 200 million to the creation of the Abel Foundation, with the intention of award- ing an international prize for outstanding research in mathematics. The prize, amounting to NOK 6 million, was insti- tuted to make up for the fact that there is no Nobel Prize for mathematics. In addi- tion to awarding the international prize, the Foundation shall contribute part of its earnings to measures for increasing inter- est in, and stimulating recruitment to, Nils Voje Johansen Yngvar Reichelt mathematical and scientific fields. The first Abel Prize was awarded in machine – the brain and the computer, break those rules creatively, just like an 2003 to the French mathematician Jean- with the subtitle “Will a computer ever be artist or a musical composer. Pierre Serre for playing a key role in shap- awarded the Abel Prize?” Quentin After a brief interval, Quentin Cooper ing the modern form of many parts of Cooper, one of the BBC’s most popular invited questions from the audience and a mathematics. In 2004, the Abel radio presenters, chaired the meeting, in number of points were brought up that Committee decided that Michael F. which Sir Michael spoke for an hour to an Atiyah addressed thoroughly and profes- Atiyah and Isadore M. -

All About Abel Dayanara Serges Niels Henrik Abel (August 5, 1802-April 6,1829) Was a Norwegian Mathematician Known for Numerous Contributions to Mathematics

All About Abel Dayanara Serges Niels Henrik Abel (August 5, 1802-April 6,1829) was a Norwegian mathematician known for numerous contributions to mathematics. Abel was born in Finnoy, Norway, as the second child of a dirt poor family of eight. Abels father was a poor Lutheran minister who moved his family to the parish of Gjerstad, near the town of Risr in southeast Norway, soon after Niels Henrik was born. In 1815 Niels entered the cathedral school in Oslo, where his mathematical talent was recognized in 1817 by his math teacher, Bernt Michael Holmboe, who introduced him to the classics in mathematical literature and proposed original problems for him to solve. Abel studied the mathematical works of the 17th-century Englishman Sir Isaac Newton, the 18th-century German Leonhard Euler, and his contemporaries the Frenchman Joseph-Louis Lagrange and the German Carl Friedrich Gauss in preparation for his own research. At the age of 16, Abel gave a proof of the Binomial Theorem valid for all numbers not only Rationals, extending Euler's result. Abels father died in 1820, leaving the family in straitened circumstances, but Holmboe and other professors contributed and raised funds that enabled Abel to enter the University of Christiania (Oslo) in 1821. Abels first papers, published in 1823, were on functional equations and integrals; he was the first person to formulate and solve an integral equation. He had also created a proof of the impossibility of solving algebraically the general equation of the fifth degree at the age of 19, which he hoped would bring him recognition. -

Nordlit 29, 2012 NORSK-RUSSISKE VITENSKAPELIGE RELASJONER

NORSK-RUSSISKE VITENSKAPELIGE RELASJONER INNEN ARKTISK FORSKNING 1814-1914 Kari Aga Myklebost Vitenskapshistorikere har pekt på at de femti årene forut for 1. verdenskrig, som ofte betegnes som nasjonalismens epoke, hadde sterke internasjonale trender.1 Det foregikk internasjonaliseringsprosesser innenfor et bredt spekter av samfunnssektorer, som industri, handel, finans, politikk og demografi. Denne utviklinga hadde nær sammenheng med de tekniske nyvinningene innenfor transport og kommunikasjoner, som førte til økte muligheter for samkvem over landegrenser og bredere bevissthet om endringer i andre land. Internasjonaliseringa innenfor vitenskapen var i tillegg nært knyttet til profesjonaliseringa og institusjonaliseringa av forskningssektoren i andre halvdel av 1800-tallet. Dette foregikk som parallelle prosesser i en rekke land. Vitenskapen var en sektor i ekspansjon, både kvantitativt, kvalitativt og organisatorisk, - og samtidig en sektor som levde i spennet mellom nasjonalisering og internasjonalisering. Nasjonaliseringsprosessene innenfor polarforskninga kjenner vi godt; det handlet om fronting av nasjonalstatens interesser og status gjennom vitenskapelige oppdagelser og nyvinninger. Prosessene i retning av internasjonalisering hadde en todelt bakgrunn: For det første var de basert på tradisjonene fra 1600- og 1700-tallets Republic of Letters eller de lærdes republikk på tvers av landegrenser, hvor latin og etter hvert også tysk sto sterkt som felles akademisk arbeidsspråk. For det andre hadde de opphav i en erkjennelse av at de profesjonaliserte, nye vitenskapsdisiplinene var avhengige av internasjonal koordinering, kommunikasjon og samarbeid for å oppnå gode forskningsresultater. Det har også blitt pekt på et økende behov for å sikre kognitiv homogenitet, eller felles begreps- og forståelsesrammer, etter hvert som antallet forskningsdisipliner og forskere økte i ulike land.2 I tiårene fra ca 1860 og fram mot 1914 ble det etablert en rekke internasjonale vitenskapelige møteplasser i form av kongresser og organisasjoner. -

Éclat a Mathematics Journal

Éclat A Mathematics Journal Volume I 2010 Department of Mathematics Lady Shri Ram College For Women Éclat A Mathematics Journal Volume I 2010 To Our Beloved Teacher Mrs. Santosh Gupta for her 42 years of dedication Preface The revival of Terminus a quo into E´clat has been a memorable experience. Eclat´ , with its roots in french, means brilliance. The journey from the origin of Terminus a quo to the brilliance of E´clat is the journey we wish to undertake. In our attempt to present diverse concepts, we have divided the journal into four sections - History of Mathematics, Rigour in Mathematics, Extension of Course Contents and Interdisciplinary Aspects of Mathematics. The work contained here is not original but consists of the review articles contributed by both faculty and students. This journal aims at providing a platform for students who wish to publish their ideas and also other concepts they might have come across. Our entire department has been instrumental in the publishing of this journal. Its compilation has evolved after continuous research and discussion. Both the faculty and the students have been equally enthusiastic about this project and hope such participation continues. We hope that this journal would become a regular annual feature of the department and would encourage students to hone their skills in doing individual research and in writing academic papers. It is an opportunity to go beyond the prescribed limits of the text and to expand our knowledge of the subject. Dootika Vats Ilika Mohan Rangoli Jain Contents Topics Page 1) History of Mathematics 1 • Abelia - The Story of a Great Mathematician 2 • Geometry in Ancient Times 6 2) Rigour in Mathematics 10 • Lebesgue Measure and Integration 11 • Construction of the Real Number System 18 • Fuzzy Logic in Action 25 3) Extension of Course Contents 29 • Continuum Hypothesis 30 • Dihedral Groups 35 4) Inter-disciplinary Aspects of Mathematics 41 • Check Digits 42 • Batting Average 46 1 History of Mathematics The history behind various mathematical concepts and great mathemati- cians is intriguing. -

Locked in Ice: Parts

Locked in A spellbinding biography of Fridtjof Nansen, the Ice pioneer of polar exploration, with a spotlight on his harrowing three-year journey to the top of the world. An explorer who many adventurers argue ranks alongside polar celebrity Ernest Shackleton, Fridtjof Nansen contributed tremendous amounts of new Nansen’s Daring Quest information to our knowledge about the Polar Arctic. At North Pole a time when the North Pole was still undiscovered for the territory, he attempted the journey in a way that most experts thought was mad: Nansen purposefully locked his PETER LOURIE ship in ice for two years in order to float northward along the currents. Richly illustrated with historic photographs, -1— —-1 Christy Ottaviano Books 0— this riveting account of Nansen's Arctic expedition —0 Henry Holt and Company +1— celebrates the legacy of an extraordinary adventurer who NEW YORK —+1 pushed the boundaries of human exploration to further science into the twentieth century. 3P_EMS_207-74305_ch01_0P.indd 2-3 10/15/18 1:01 PM There are many people I’d like to thank for help researching and writing this book. First, a special thank- you to Larry Rosler and Geoff Carroll, longtime friends and wise counselors. Also a big thank- you to the following: Anne Melgård, Guro Tangvald, and Jens Petter Kollhøj at the National Library of Norway in Oslo; Harald Dag Jølle of the Norwegian Polar Institute, in Tromsø; Karen Blaauw Helle, emeritus professor of physiology, Department of Biomedicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; Carl Emil Vogt, University of Oslo and the Center for Studies of Holocaust and Religious Minorities; Susan Barr, se nior polar adviser, Riksantikvaren/Directorate for Cultural Heritage; Dr. -

Henningsmoen, G

92 THE ORDOVICIAN OF THE OSLO REGION A SHORT HISTORY OF RES EARCH Gunnar Henningsmoen INTRODUCT ION The Oslo Region (Oslofeltet) is not an administrative unit but a term introduced by geologists. At first referred to as 'Christianias Overgangs-Territorium' (the 'overgang' or transition relating to geological age) or 'Christiania-territoriet' (Keilhau 1826), it later became known as 'Kristianiafeltet' and finally 'Oslofeltet' when the old name of Oslo was reintroduced for the capital in 1925. The Oslo Region varies in width from 40 to 75 km and extends a distance of approximately 115 km both north and south of Oslo, which is situated at its eastern border. The region is fault controlled (Oslo Graben) and covers an area of roughly lO 000 square km. It is bordered by Precambrian in the west and east and by the Caledonian nappe region in the north. Within the region, Upper Palaeozoic, mostly igneous, rocks are slightly greater in areal extent than the Lower Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks. Ordovician rocks cover around 2 000 square km and crop out in eleven districts established by Størmer (1953). THE ORDOVICIAN SYSTEM IN THE OSLO REGION In the early 1800's, strata now assigned to the Ordovician were not distinguished as a separate unit, but were included in the 'Uebergangs gebirge' (transitional rocks), a concept introduced in Germany in the late 1790's by Abraham G. Werner for rocks between the 'Urgebirge' (ancient rocks) and the 'Flotzgebirge' (Coal Measures and younger). Thus the German geologist von Buch (1810), after having travelled in Scandinavia, assigned all the rocks of the Oslo Region to the 'Uebergangs formation'. -

Catalogue of Place Names in Northern East Greenland

Catalogue of place names in northern East Greenland In this section all officially approved, and many Greenlandic names are spelt according to the unapproved, names are listed, together with explana- modern Greenland orthography (spelling reform tions where known. Approved names are listed in 1973), with cross-references from the old-style normal type or bold type, whereas unapproved spelling still to be found on many published maps. names are always given in italics. Names of ships are Prospectors place names used only in confidential given in small CAPITALS. Individual name entries are company reports are not found in this volume. In listed in Danish alphabetical order, such that names general, only selected unapproved names introduced beginning with the Danish letters Æ, Ø and Å come by scientific or climbing expeditions are included. after Z. This means that Danish names beginning Incomplete documentation of climbing activities with Å or Aa (e.g. Aage Bertelsen Gletscher, Aage de by expeditions claiming ‘first ascents’ on Milne Land Lemos Dal, Åkerblom Ø, Ålborg Fjord etc) are found and in nunatak regions such as Dronning Louise towards the end of this catalogue. Å replaced aa in Land, has led to a decision to exclude them. Many Danish spelling for most purposes in 1948, but aa is recent expeditions to Dronning Louise Land, and commonly retained in personal names, and is option- other nunatak areas, have gained access to their al in some Danish town names (e.g. Ålborg or Aalborg region of interest using Twin Otter aircraft, such that are both correct). However, Greenlandic names be - the remaining ‘climb’ to the summits of some peaks ginning with aa following the spelling reform dating may be as little as a few hundred metres; this raises from 1973 (a long vowel sound rather than short) are the question of what constitutes an ‘ascent’? treated as two consecutive ‘a’s. -

Peter Waage – Kjemiprofessoren Fra Hidra

Peter Waage kjemiprofessoren fra Hidra Av Bjørn Pedersen Skolelaboratoriet – kjemi, UiO Skolelaboratoriet – kjemi UiO 2007 ISBN-13 978-82-91183-07-7 ISBN-10 82-91183-07-4 1. utgave 2. opplag med rettelser. Det må ikke kopieres fra denne bok i strid med lover eller avtaler. Omslag og omslagsfoto: Bjørn Pedersen Henvendelser om heftet kan rettes til forfatteren: [email protected] Trykk: Reprosentralen Forsidebilde viser øverst Frederiksgate 3 – Domus Chemica fra 1875 til 1934. Nederst til høyre et utsnitt av maleriet av Peter Waage malt av Bjarne Falk i 1907 etter fotografiet på side 61. Maleriet henger i møterom VU 24 på Kjemisk instituttet. Seglet er tatt fra Forelesningskatalogen fra vårsemesteret 1920. Figuren er av den greske guden Apollon – en mann selv om figuren ikke ser slik ut. Et slikt segl har vært i bruk som universitetets lakkstempel i så lenge universitetet het Det kongelige Frederiks universitet (Universitatis Regia Fredericiana) fra 1814 til 1938. (Tove Nielsen: Nei dessverre ... Apollon 7 (2000).) Forord Peter Waage er den mest berømte norske kjemiker på 1800-tallet. Takket være massevirkningsloven lever hans navn videre i kjemibøker over hele verden. Han kom fra Hidra - en liten øy mellom Øst- og Vestlandet som den gang, da trafikken gikk lettere til sjøs enn på land, var mer internasjonal enn Christiania. Hva slags mann var han? Hva er egentlig massevirkningsloven? Hva gjorde han ellers? Kjemien hadde sin storhetstid på 1800-tallet. Da fikk kjemien sitt eget språk hvor de kjemiske symbolene for grunnstoffene var bokstavene, formlene var ordene og reaksjonsligningene var setningene. Analysemetodene ble forbedret og mange nye stoffer ble fremstilt. -

Articles in Newspapers and Journals and Made Lecture Tours All Over Scan- Dinavia and Germany, Contributing to Enhance the Public Educational Level and Awareness

CMYK RGB Hist. Geo Space Sci., 3, 53–72, 2012 History of www.hist-geo-space-sci.net/3/53/2012/ Geo- and Space doi:10.5194/hgss-3-53-2012 © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Access Open Sciences Advances in Science & Research Sophus Peter Tromholt: an outstanding pioneerOpen inAccess Proceedings auroral research Drinking Water Drinking Water K. Moss1 and P. Stauning2 Engineering and Science Engineering and Science 1Guldborgvej 15, st.tv., 2000 Frederiksberg, Denmark Open Access Access Open Discussions 2Danish Meteorological Institute (emeritus), Lyngbyvej 100, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Correspondence to: K. Moss ([email protected]) Discussions Earth System Earth System Received: 14 November 2011 – Revised: 12 February 2012 – Accepted: 18 February 2012 – Published: 7 March 2012 Science Science Abstract. The Danish school teacher Sophus Peter Tromholt (1851–1896) was self-taught in physics, astron- Open Access Open omy, and auroral sciences. Still, he was one of the brightest auroral researchers of the 19th century.Access Open Data He was the Data first scientist ever to organize and analyse correlated auroral observations over a wide area (entire Scandinavia) moving away from incomplete localized observations. Tromholt documented the relation between auroras and Discussions sunspots and demonstrated the daily, seasonal and solar cycle-related variations in high-latitude auroral oc- currence frequencies. Thus, Tromholt was the first ever to deduce from auroral observations theSocial variations Social associated with what is now known as the auroral oval termed so by Khorosheva (1962) and Feldstein (1963) Open Access Open Geography more than 80 yr later. He made reliable and accurate estimates of the heights of auroras several decadesAccess Open Geography before this important issue was finally settled through Størmer’s brilliant photographic technique. -

Geomagnetic Research in the 19Th Century: a Case Study of the German Contribution

Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 63 (2001) 1649–1660 www.elsevier.com/locate/jastp Geomagnetic research in the 19th century: a case study of the German contribution Wilfried Schr,oder ∗, Karl-Heinrich Wiederkehr Geophysical Institute, Hechelstrasse 8, D 28777 Bremen, Germany Received 20 October 2000; received in revised form 2 March 2001; accepted 1 May 2001 Abstract Even before the discovery of electromagnetism by Oersted, and before the work of AmpÂere, who attributed all magnetism to the 7ux of electrical currents, A.v. Humboldt and Hansteen had turned to geomagnetism. Through the “G,ottinger Mag- netischer Verein”, a worldwide cooperation under the leadership of Gauss came into existence. Even today, Gauss’s theory of geomagnetism is one of the pillars of geomagnetic research. Thereafter, J.v. Lamont, in Munich, took over the leadership in Germany. In England, the Magnetic Crusade was started by the initiative of John Herschel and E. Sabine. At the beginning of the 1840s, James Clarke Ross advanced to the vicinity of the southern magnetic pole on the Antarctic Continent, which was then quite unknown. Ten years later, Sabine was able to demonstrate solar–terrestrial relations from the data of the colonial observatories. In the 1980s, Arthur Schuster, following Balfour Stewart’s ideas, succeeded in interpreting the daily variations of the electrical process in the high atmosphere. Geomagnetic research work in Germany was given a fresh impetus by the programme of the First Polar Year 1882–1883. Georg Neumayer, director of the “Deutsche Seewarte” in Hamburg, was one of the initiators of the Polar Year. -

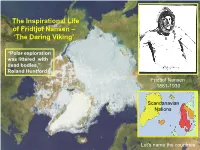

Nansen Talk NHS2

The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ “Polar exploration was littered with dead bodies,” Roland Huntford Fridtjof Nansen 1861-1930 Scandanavian Nations Let’s name the countries The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ “Polar exploration was littered with dead bodies,” Roland Huntford Fridtjof Nansen 1861-1930 F The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ “Polar exploration was littered with dead bodies,” Roland Huntford Fridtjof Nansen 1861-1930 F S The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ “Polar exploration was littered with dead bodies,” Roland Huntford Fridtjof Nansen 1861-1930 F S N The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ “Polar exploration was littered with dead bodies,” Roland Huntford Fridtjof Nansen 1861-1930 F S N D The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ “Polar exploration was littered with dead bodies,” Roland Huntford Fridtjof Nansen 1861-1930 F I S N D The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ “Polar exploration was littered with dead bodies,” Roland Huntford Fridtjof Nansen 1861-1930 G (D) F I S N D The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ “Polar exploration was littered with dead bodies,” Roland Huntford Fridtjof Nansen 1861-1930 G Sp (D) (N) F I S N D The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ Events of Period ???? 1861-1865 ???? 1880‟s Fridtjof Nansen ???? 1861-1930 1914-1918 ???? 1919 ???? 1920‟s Fram:1890’s Kodak Brownie Camera The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ Events of Period U.S. Civil War 1861-1865 ???? 1880‟s Fridtjof Nansen ???? 1861-1930 1914-1918 ???? 1919 ???? 1920‟s Fram:1890’s Kodak Brownie Camera The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ Events of Period U.S.