Love That Moves the Sun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acollection of Correspondence

© 2012 Capuchin Friars of Australia. All Rights Reserved. A COLLECTION OF CORRESPONDENCE Some Letters … and other things, from Sixteenth Century Italy in their original languages Bernardo, ben potea bastarvi averne Co’l dolce dir, ch’a voi natura infonde, Qui dove ‘l re de’ fiume ha più chiare onde, Acceso i cori a le sante opre eterne; Ché se pur sono in voi pure l’interne Voglie, e la vita al destin corrisponde, Non uom di frale carne e d’ossa immonde, Ma sète un voi de le schiere sperne. Or le finte apparenze, e ‘l ballo, e ‘l suono, Chiesti dal tempo e da l’antica usanza, A che così da voi vietate sono? Non fôra santità,capdox fôra arroganza Tôrre il libero arbitrio, il maggior dono Che Dio ne diè ne la primera stanza.1 Compiled by Paul Hanbridge Fourth edition, formerly “A Sixteenth Century Carteggio” Rome, 2007, 2008, Dec 2009 1 “Bernardo, it should be enough for you / With that sweet speech infused in you by Nature, / To light our hearts to high eternal works, / Here where the King of Rivers flows most clearly. / Since your own inner wishes are sincere, / And your own life reflects a pure intent, / You’re ra- ther an inhabitant of heaven. /As to these masquerades, dances, and music, /Sanctioned by time and by ancient custom - /Why do you now forbid them in your sermons? /Holiness it is not, but arrogance to take away free will, the highest gift/ Which God bestowed on us from the begin- ning.” Tullia d’Aragona (c. -

Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform

6 RENAISSANCE HISTORY, ART AND CULTURE Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform of Politics Cultural the and III Paul Pope Bryan Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Renaissance History, Art and Culture This series investigates the Renaissance as a complex intersection of political and cultural processes that radiated across Italian territories into wider worlds of influence, not only through Western Europe, but into the Middle East, parts of Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It will be alive to the best writing of a transnational and comparative nature and will cross canonical chronological divides of the Central Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Renaissance History, Art and Culture intends to spark new ideas and encourage debate on the meanings, extent and influence of the Renaissance within the broader European world. It encourages engagement by scholars across disciplines – history, literature, art history, musicology, and possibly the social sciences – and focuses on ideas and collective mentalities as social, political, and cultural movements that shaped a changing world from ca 1250 to 1650. Series editors Christopher Celenza, Georgetown University, USA Samuel Cohn, Jr., University of Glasgow, UK Andrea Gamberini, University of Milan, Italy Geraldine Johnson, Christ Church, Oxford, UK Isabella Lazzarini, University of Molise, Italy Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Bryan Cussen Amsterdam University Press Cover image: Titian, Pope Paul III. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy / Bridgeman Images. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 252 0 e-isbn 978 90 4855 025 8 doi 10.5117/9789463722520 nur 685 © B. -

Vincenzo Cappello C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Sixteenth Century Titian and Workshop Titian Venetian, 1488/1490 - 1576 Italian 16th Century Vincenzo Cappello c. 1550/1560 oil on canvas overall: 141 x 118.1 cm (55 1/2 x 46 1/2 in.) framed: 169.2 x 135.3 x 10.2 cm (66 5/8 x 53 1/4 x 4 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1957.14.3 ENTRY This portrait is known in at least four other contemporary versions or copies: in the Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Virginia[fig. 1]; [1] in the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg [fig. 2]; [2] in the Seminario Vescovile, Padua; [3] and in the Koelikker collection, Milan. [4] According to John Shearman, x-radiographs have revealed that yet another version was originally painted under the Titian workshop picture Titian and His Friends at Hampton Court (illustrated under Andrea de’ Franceschi). [5] Of these versions, the Gallery’s picture is now generally accepted as the earliest and the finest, and before it entered the Kress collection in 1954, the identity of the sitter, established by Victor Lasareff in 1923 with reference to the Hermitage version, has never subsequently been doubted. [6] Lasareff retained a traditional attribution to Tintoretto, and Rodolfo Pallucchini and W. R. Rearick upheld a similarly traditional attribution to Tintoretto of the present version. [7] But as argued by Wilhelm Suida in 1933 with reference to the Chrysler version (then in Munich), and by Fern Rusk Shapley and Harold Wethey with reference to the present version, an attribution to Titian is more likely. -

A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (F.101R – 129R) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen

A SCURRILOUS LETTER TO POPE PAUL III A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen by Paul Hanbridge PRÉCIS A Scurrilous Letter to Pope Paul III. A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen. This study introduces a transcription and English translation of a ‘Letter’ in VS 469. The document is titled: Epistola invectiva Bernhardj Occhinj in qua vita et res gestae Pauli tertij Pont. Max. describuntur . The study notes other versions of the letter located in Florence. It shows that one of these copied the VS469, and that the VS469 is the earliest of the four Mss and was made from an Italian exemplar. An apocryphal document, the ‘Letter’ has been studied briefly by Ochino scholars Karl Benrath and Bendetto Nicolini, though without reference to this particular Ms. The introduction considers alternative contemporary attributions to other authors, including a more proximate determination of the first publication date of the Letter. Mario da Mercato Saraceno, the first official Capuchin ‘chronicler,’ reported a letter Paul III received from Bernardino Ochino in September 1542. Cesare Cantù and the Capuchin historian Melchiorre da Pobladura (Raffaele Turrado Riesco) after him, and quite possibly the first generations of Capuchins, identified the1542 letter with the one in transcribed in these Mss. The author shows this identification to be untenable. The transcription of VS469 is followed by an annotated English translation. Variations between the Mss are footnoted in the translation. © Paul Hanbridge, 2010 A SCURRILOUS LETTER TO POPE PAUL III A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. -

Fire, Smoke and Vapour. Jan Brueghel's 'Poetic Hells

FIRE, SMOKE AND VAPOUR. JAN BRUEGHEL’S ‘POETIC HELLS’: ‘GHESPOOCK’ IN EARLY MODERN EUROPEAN ART Christine Göttler Karel van Mander, in the ‘Life of Jeronimus Bos’ in his Schilder-Boeck of 1604, speaks of the ‘wondrous or strange fancies’ (wonderlijcke oft seldsaem versieringhen), which this artist ‘had in his head and expressed with his brush’ – the ‘phantoms and monsters of hell ( ghespoock en ghe- drochten der Hellen) which are usually not so much kindly as ghastly to look upon’.1 Taking one of Bosch’s depictions of the Descent of Christ into the Limbo of the Fathers as an example, van Mander further notes that ‘it’s a wonder what can be seen there of odd spooks (oubolligh ghespoock); also, how subtle and natural (aerdigh en natuerlijck) he was with ames, \ res, smoke and vapours’.2 In the Schilder-Boeck, van Mander frequently uses the word ‘aerdigh’ to describe the aesthetically pleasing quality of small works or small details;3 here, ‘aerdigh’ refers to the natural and lively depiction of res. As it has been observed, van Mander’s list of Bosch’s painterly expres- sions echoes Erasmus’s often-cited eulogy on Dürer in the Dialogus de recta Latini Graecique sermonis pronuntiatione (Dialogue About the Correct Pro- nunciation of Latin and Greek), published in Basel in 1528. According to 1 Mander K. van, The Lives of the Illustrious Netherlandish and German Painters, from the \ rst edition of the Schilder-boeck (1603–1604), ed. H. Miedema, 6 vols. (Davaco: 1994–99) I 124f. (f. 216v): ‘Wie sal verhalen al de wonderlijcke oft seldsaem versieringhen/die Ieronimus Bos in’t hooft heeft ghehadt/en met den Pinceel uytghedruckt/van ghe- spoock en ghedrochten der Hellen/dickwils niet alsoo vriendlijck als grouwlijck aen te sien.’ Here and in the following, my translation is largely based on the one given in Miedema’s edition of The Lives; I use, however, a more literal translation of van Mander’s expressions. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Nelson Hubert Minnich Born

CURRICULUM VITAE Nelson Hubert Minnich Born: 15 January 1942, Cincinnati, Ohio Addresses: 5713 37th Avenue Program in Church History Hyattsville, Maryland 20782 Catholic University of America Tel. (301) 277-5891 Washington, D.C. 20064 Tel. (202) 319-5702 (office) or 5079 (CHR) Education: 1959-63 Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio) -- part time (Humanities) 1963-65 Boston College (Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts) -- AB (Philosophy) 1965-66 Boston College (Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts) -- MA (History) 1968-70 Gregorian University (Roma, Italia) -- STB (Theology) 1970-77 Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts) -- PhD (History) Dissertation: "Episcopal Reform at the Fifth Lateran Council (1512-17)" directed by Myron P. Gilmore Post-Graduate Distinctions: Foundation for Reformation Research: Junior Fellow (1971) for paleographical studies Institute of International Education: Fulbright Grant for Research in Italy (1972-73) full award for dissertation research -- resigned due to impending death in family Harvard University: Tuition plus stipend (1971-72), Staff Tuition Scholarship (1972-73, 1974- 76), Emerton Fellowship (1972-73), Harvard Traveling Fellowship (1973-74) for dissertation research Sixteenth Century Studies Conference: Carl Meyer Prize (1977) National Endowment for the Humanities: Summer Stipend (1978) to work on the "Protestatio" of Alberto Pio Villa I Tatti: The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies: Fellowship for the summer (1979) to study Leo X's concern for doctrine prior to Luther American Academy -

The Roots of the Fondazione Roma: the Historical Archives

The Historical Archives are housed in the head-offices of the Fondazione Roma, situated in the THE ROOTS OF THE FONDAZIONE ROMA: THE HISTORICAL prestigious Palazzo Sciarra which was built in the second half of the sixteenth century by the ARCHIVES Sciarra branch of the Colonna family who held the Principality of Carbognano. Due to the beauty of the portal, the Palace was included amongst the ‘Four Wonders of Rome’ together with the In 2010, following a long bureaucratic procedure marked by the perseverance of the then Borghese cembalo, the Farnese cube and the Caetani-Ruspoli staircase. During the eighteenth Chairman, now Honorary President, Professor Emmanuele F.M. Emanuele, Fondazione Roma century, Cardinal Prospero Colonna renovated the Palace with the involvement of the famous acquired from Unicredit a considerable amount of records that had been accumulated over five architect Luigi Vanvitelli. The Cardinal’s Library, the small Gallery and the Mirrors Study, richly hundred years, between the sixteenth and the twentieth century, by two Roman credit institutions: decorated with paintings, are some of the rooms which were created during the refurbishment. the Sacro Monte della Pietà (Mount of Piety) and the savings bank Cassa di Risparmio. The documents are kept inside a mechanical and electric mobile shelving system placed in a depot The Honorary President Professor Emanuele declares that “The Historical Archives are a precious equipped with devices which ensure safety, the stability and constant reading of the environmental source both for historians and those interested in the vicissitudes of money and credit systems and indicators and respect of the standards of protection and conservation. -

The Story of the Borgias (1913)

The Story of The Borgias John Fyvie L1BRARV OF UN ,VERSITV CALIFORNIA AN DIEGO THE STORY OF THE BORGIAS <Jt^- i//sn6Ut*4Ccn4<s flom fte&co-^-u, THE STORY OF THE BOEGIAS AUTHOR OF "TRAGEDY QUEENS OF THE GEORGIAN ERA" ETC NEW YORK G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS 1913 PRINTED AT THE BALLANTYNE PRESS TAVI STOCK STREET CoVENT GARDEN LONDON THE story of the Borgia family has always been of interest one strangely fascinating ; but a lurid legend grew up about their lives, which culminated in the creation of the fantastic monstrosities of Victor Hugo's play and Donizetti's opera. For three centuries their name was a byword for the vilest but in our there has been infamy ; own day an extraordinary swing of the pendulum, which is hard to account for. Quite a number of para- doxical writers have proclaimed to an astonished and mystified world that Pope Alexander VI was both a wise prince and a gentle priest whose motives and actions have been maliciously mis- noble- represented ; that Cesare Borgia was a minded and enlightened statesman, who, three centuries in advance of his time, endeavoured to form a united Italy by the only means then in Lucrezia anybody's power ; and that Borgia was a paragon of all the virtues. " " It seems to have been impossible to whitewash the Borgia without a good deal of juggling with the evidence, as well as a determined attack on the veracity and trustworthiness of the contemporary b v PREFACE historians and chroniclers to whom we are indebted for our knowledge of the time. -

Leonardo Da Vinci and the Persistence of Myth Emily Hanson

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2012 Inventing the Sculptor: Leonardo da Vinci and the Persistence of Myth Emily Hanson Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hanson, Emily, "Inventing the Sculptor: Leonardo da Vinci and the Persistence of Myth" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 765. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/765 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Art History & Archaeology INVENTING THE SCULPTOR LEONARDO DA VINCI AND THE PERSISTENCE OF MYTH by Emily Jean Hanson A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2012 Saint Louis, Missouri ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wouldn’t be here without the help and encouragement of all the following people. Many thanks to all my friends: art historians, artists, and otherwise, near and far, who have sustained me over countless meals, phone calls, and cappuccini. My sincere gratitude extends to Dr. Wallace for his wise words of guidance, careful attention to my work, and impressive example. I would like to thank Campobello for being a wonderful mentor and friend, and for letting me persuade her to drive the nearly ten hours to Syracuse for my first conference, which convinced me that this is the best job in the world. -

Introduction: the Spirituali and Their Goals

NOT BY FAITH ALONE: VITTORIA COLONNA, MICHELANGELO AND REGINALD POLE AND THE EVANGELICAL MOVEMENT IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY ITALY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Christopher Allan Dunn, J.D. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. March 19, 2014 NOT BY FAITH ALONE: VITTORIA COLONNA, MICHELANGELO AND REGINALD POLE AND THE EVANGELICAL MOVEMENT IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY ITALY Christopher Allan Dunn, J.D. MALS Mentor: Michael Collins, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Beginning in the 1530’s, groups of scholars, poets, artists and Catholic Church prelates came together in Italy in a series of salons and group meetings to try to move themselves and the Church toward a concept of faith that was centered on the individual’s personal relationship to God and grounded in the gospels rather than upon Church tradition. The most prominent of these groups was known as the spirituali, or spiritual ones, and it included among its members some of the most renowned and celebrated people of the age. And yet, despite the fame, standing and unrivaled access to power of its members, the group failed utterly to achieve any of its goals. By 1560 all of the spirituali were either dead, in exile, or imprisoned by the Roman Inquisition, and their ideas had been completely repudiated by the Church. The question arises: how could such a “conspiracy of geniuses” have failed so abjectly? To answer the question, this paper examines the careers of three of the spirituali’s most prominent members, Vittoria Colonna, Michelangelo and Reginald Pole. -

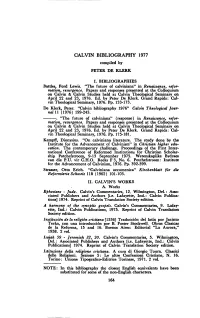

1977 Compiled by PETER DE KLERK

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1977 compiled by PETER DE KLERK I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Battles, Ford Lewis. "The future of calviniana" in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 133-173. De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1976" Calvin Theological Jour- nal U (1976) 199-243. -. "The future of calviniana" (response) in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 175-181. Kempff, Dionysius. "On calviniana literature. The study done by the Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism" in Christian higher edu cation. The contemporary challenge. Proceedings of the First Inter national Conference of Reformed Institutions for Christian Scholar ship Potchefstroom, 9-13 September 1975. Wetenskaplike Bydraes van die P.U. vir C.H.O. Reeks F 3, No. 6. Potchefstroom: Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism, 1976. Pp. 392-399. Strasser, Otto Erich. "Calviniana œcumenica" Kirchenblatt für die Reformierte Schweiz 118 (1962) 101-103. II. CALVIN'S WORKS A. Works Ephesians - Jude. Calvin's Commentaries, 12. Wilmington, Del.: Asso ciated Publishers and Authors [i.e. Lafayette, Ind.: Calvin Publica tions] 1974. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. A harmony of the synoptic gospels. Calvin's Commentaries, 9. Lafay ette, Ind.: Calvin Publications, 1975. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. Institución de la religion cristiana fi536] Traducción del latín por Jacinto Terán, con una introducción por Β. -

A Few Clerics at Court

Rafferty 1 A Few Clerics at Court Catholic Clergymen in the lay politics and administration of Spain during the reigns of “Los Austrias Mayores”, Charles V/I and Philip II: 1516-1598 Keith Rafferty History Undergraduate Honors Thesis Georgetown University Advisor: Professor Tommaso Astarita, Georgetown University May 9. 2011 Rafferty 2 I authorize the public release of my thesis for anybody who should want to look at it. Rafferty 3 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Thesis Statement.................................................................................................................................. 8 Organization and Explanation .................................................................................................................. 9 Explanation of Terms .......................................................................................................................... 9 CODOIN ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Spain/The Spanish Empire ......................................................................................................... 11 The Spanish Aristocracy ...........................................................................................................