Trafodion November 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace The Crystal Palace was a cast-iron and plate-glass structure originally The Crystal Palace built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. More than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000-square-foot (92,000 m2) exhibition space to display examples of technology developed in the Industrial Revolution. Designed by Joseph Paxton, the Great Exhibition building was 1,851 feet (564 m) long, with an interior height of 128 feet (39 m).[1] The invention of the cast plate glass method in 1848 made possible the production of large sheets of cheap but strong glass, and its use in the Crystal Palace created a structure with the greatest area of glass ever seen in a building and astonished visitors with its clear walls and ceilings that did not require interior lights. It has been suggested that the name of the building resulted from a The Crystal Palace at Sydenham (1854) piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 General information wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Status Destroyed Exhibition, referring to a "palace of very crystal".[2] Type Exhibition palace After the exhibition, it was decided to relocate the Palace to an area of Architectural style Victorian South London known as Penge Common. It was rebuilt at the top of Town or city London Penge Peak next to Sydenham Hill, an affluent suburb of large villas. It stood there from 1854 until its destruction by fire in 1936. The nearby Country United Kingdom residential area was renamed Crystal Palace after the famous landmark Coordinates 51.4226°N 0.0756°W including the park that surrounds the site, home of the Crystal Palace Destroyed 30 November 1936 National Sports Centre, which had previously been a football stadium Cost £2 million that hosted the FA Cup Final between 1895 and 1914. -

The Restoration of Belle Vue Park, Newport by John Woods

No. 53 Winter 2008/09 The restoration of Belle Vue Park, Newport by John Woods Park Square was the first public park to open in Newport. remained intact, the park has developed steadily since the mid Today it lies behind a multi-storey car park of the same name 1890s with the Council adding additional features and on Commercial Street in the heart of the busy city centre. In facilities sometimes as a result of direct public pressure. In the 1880s this little park was reported as mainly serving as a 1896 the Gorsedd Circle was added in readiness for the meeting place and playground for children, but by 1889 , National Eisteddfod which was held in Newport for the first when Councillor Mark Mordey approached the local time in 1897. In the early 1900s , following public pressure , landowner Lord Tredegar, the Corporation clearly had sporting facilities were added: two bowling rinks in 1904 and aspirations to build a public park that befitted the status of tennis courts in 1907. The present-day bowls pavilion was the developing town. built in 1934 and is located centrally between two full size flat In 1891 following the Town Council’s decision “That a bowling greens. Whilst the park pavilion and conservatories public park should be procured for the town in some suitable were completed in readiness for the official opening, the locality” , Lord Tredegar expressed an interest in presenting a demand for additional space for both refreshments and shelter site to Newport . The following year the fields lying between brought about the building of the Rustic Tea House in 1910. -

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE STRATEGY March 2019

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE STRATEGY March 2019 Volume 1 Strategic Framework Monmouth CONTENTS Key messages 1 Setting the Scene 1 2 The GIGreen Approach Infrastructure in Monmouthshire Approach 9 3 3 EmbeddingGreen Infrastructure GI into Development Strategy 25 4 PoSettlementtential GI Green Requirements Infrastructure for Key Networks Growth Locations 51 Appendices AppendicesA Acknowledgements A B SGISources Database of Advice BC GIStakeholder Case Studies Consultation Record CD InformationStrategic GI Networkfrom Evidence Assessment: Base Studies | Abergavenny/Llanfoist D InformationD1 - GI Assets fr Auditom Evidence Base Studies | Monmouth E InformationD2 - Ecosystem from Services Evidence Assessment Base Studies | Chepstow F InformationD3 - GI Needs fr &om Opportunities Evidence Base Assessment Studies | Severnside Settlements GE AcknowledgementsPlanning Policy Wales - Green Infrastructure Policy This document is hyperlinked F Monmouthshire Wellbeing Plan Extract – Objective 3 G Sources of Advice H Biodiversity & Ecosystem Resilience Forward Plan Objectives 11128301-GIS-Vol1-F-2019-03 Key Messages Green Infrastructure Vision for Monmouthshire • Planning Policy Wales defines Green Infrastructure as 'the network of natural Monmouthshire has a well-connected multifunctional green and semi-natural features, green spaces, rivers and lakes that intersperse and infrastructure network comprising high quality green spaces and connect places' (such as towns and villages). links that offer many benefits for people and wildlife. • This Green Infrastructure -

Cht Highbury Landscape History 1878-Present and Restoration Proposals

1 CHT HIGHBURY LANDSCAPE HISTORY 1878-PRESENT AND RESTORATION PROPOSALS © Chamberlain Highbury Trust 2021 2 CHT HIGHBURY LANDSCAPE HISTORY 1878-PRESENT AND RESTORATION PROPOSALS Introduction The gardens of Highbury are of considerable historic importance and a great asset to Birmingham. They were laid out from 1879 to 1914 and were the creation of Joseph Chamberlain the head of Birmingham’s most distinguished political family, who employed the well-known landscape architect, Edward Milner, and subsequently his son Henry. In their day the gardens of Highbury were the most renowned in Birmingham, and possibly the West Midlands. They were widely written about in the national press and provided the setting for Chamberlain’s entertaining of leading politicians and his Birmingham associates. The fame of Highbury was due to the fact that within the thirty acres there were many different features and these contributed to the feel of being in the country on a large estate rather than in the suburbs of a major industrial city. They display the quintessence of high Victorian taste in gardening, and, moreover the taste of one man having been created on an undeveloped agricultural site and having remained largely intact and substantially unaltered since Joseph Chamberlain’s death in 1914. The fact that much of the grounds became a public park in 1921and the rest remained with Chamberlain’s former home which became an institution, has resulted in their preservation from development. The significance of the Highbury landscape is recognised by its listing at Grade 11 on the E H Register of Gardens and Parks of Special Historical Significance. -

Vicarage Cottage Cover.Indd

Vicarage Cottage Bakewell | Derbyshire | DE45 1FE VICARAGE COTTAGE Introducing Vicarage Cottage, formerly the gardener’s cottage, coach house and stables to the adjacent Vicarage, the property was originally constructed in 1870 and designed by the noted architect Alfred Waterhouse whose other commissions included the Manchester Assize Court and Manchester Town Hall. Boasting three spacious bedrooms, three large reception rooms (one of which could be a ground floor bedroom) a modern, recently updated kitchen, a fully operational passenger lift ideal for those with mobility challenges, and a bespoke spiral staircase. Adjoining the house is a tandem garage and single garage, for which planning permission to create further accommodation has been granted. Sitting on a good-sized plot (0.41 acres) with mature gardens, tucked away on a private road, Vicarage Cottage is within walking distance of all local amenities, schools and shops, yet peaceful and separate from the hustle and bustle of the town centre. Bakewell is home to both of the popular and renowned schools, Lady Manners School and St. Anselm’s Preparatory School. KEY FEATURES Ground Floor On entering the property through the original high arched coach house doorway, an abundance of features, such as high ceilings, large doorways, deep skirting boards, and original stable fittings immediately offer the viewer a sense of the history of the house. The ground floor boasts ample flexible use options and has three good sized reception rooms, the first of which is a family dining room with large picture windows, a mirrored wall which further reflects the light and creates the illusion of more space. -

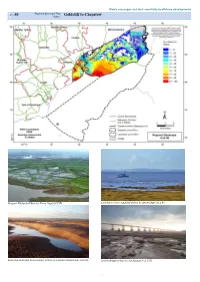

Goldcliff to Chepstow Name

Welsh seascapes and their sensitivity to offshore developments No: 50 Regional Seascape Unit Goldcliff to Chepstow Name: Newport Wetlands (Photo by Kevin Dupé,©CCW) Looking across to England (Photo by Kevin Dupé,©CCW) Extensive sand flats in the estuary (Photo by Charles Lindenbaum ©CCW) Severn Bridge (Photo by Ian Saunders ©CCW) 1 Welsh seascapes and their sensitivity to offshore developments No: 50 Regional Seascape Unit Goldcliff to Chepstow Name: Seascape Types: TSLR Key Characteristics A relatively linear, reclaimed coastline with grass bund sea defences and extensive sand and mud exposed at low tide. An extensive, flat hinterland (Gwent Levels), with pastoral and arable fields up to the coastal edge. The M4 and M48 on the two Severn bridges visually dominate the area and power lines are also another major feature. Settlement is generally set back from the coast including Chepstow and Caldicot with very few houses directly adjacent, except at Sudbrook. The Severn Estuary has a strong lateral flow, a very high tidal range, is opaque with suspended solids and is a treacherous stretch of water. The estuary is a designated SSSI, with extensive inland tracts of considerable ecological variety. Views from the coastal path on bund, country park at Black Rock and the M4 and M48 roads are all important. Road views are important as the gateway views to Wales. All views include the English coast as a backdrop. Key cultural associations: Gwent Levels reclaimed landscape, extensive historic landscape and SSSIs, Severn Bridges and road and rail communications corridor. Physical Geology Triassic rocks with limited sandstone in evidence around Sudbrook. -

Catalogue 60

CATALOGUE 60 DIAMOND JUBILEE CATALOGUE A SPECIAL COLLECTION OF ROYAL AUTOGRAPHS AND MANUSCRIPTS FROM ELIZABETH I TO ELIZABETH II To Commemorate the Celebration of the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II I have put together a collection of Royal documents and photographs spanning the 400 years from the first Elizabethan age of ‘Gloriana’ to our own Elizabethan era. It includes every King and Queen in between and many of their children and grandchildren. All purchases will be sent by First Class Mail. All material is mailed abroad by Air. Insurance and Registration will be charged extra. VAT is charged at the Standard rate on Autograph Letters sold in the EEC, except in the case of manuscripts bound in the form of books. My VAT REG. No. is 341 0770 87. The 1993 VAT Regulations affect customers within the European Community. PAYMENT MAY BE MADE BY VISA, BARCLAYCARD, ACCESS, MASTERCARD OR AMEX from all Countries. Please quote card number, expiry date and security code together with your name and address and please confirm answerphone orders by fax or email. There is a secure ordering facility on my website. All material is guaranteed genuine and in good condition unless otherwise stated. Any item may be returned within three days of receipt. COVER PHOTOGRAPHY: Thomas Harrison Anthony & Austin James Farahar http://antiquesphotography.wordpress.com E-mail: [email protected] 66a Coombe Road, Kingston, KT2 7AE Tel: 07843 348748 PLEASE NOTE THAT ILLUSTRATIONS ARE NOT ACTUAL SIZE SOPHIE DUPRÉ Horsebrook House, XV The Green, Calne, -

Holst in an Unusual Circle (PDF)

Holst in an unusual circle Tom Clarke, © 2014 For a man with socialist sympathies, and famed for his simple and modest life, it is ironic that Gustav Holst once gained support from Rolls-Royce, the very epitome of luxury and exclusiveness. But there was a human side to this story that probably accounts for Holst moving within this circle for a few years. His contact with Rolls-Royce involved someone like himself who preferred to keep out of the limelight. The Commercial Managing Director of Rolls-Royce Ltd. from 1906, and soon its full managing director, was Claude Goodman Johnson (1864-1926), a man of liberal outlook. He was one of seven children, born to a religious father who worked first in the glove trade and then at the South Kensington Museum, teaching himself much about art for self improvement. He instilled a love of church music and Bach into his children. Of Claude’s brothers, Cyril Leslie became a composer, Douglas a Canon of Manchester cathedral, and Basil succeeded him briefly at Rolls- Royce Ltd. Although not artistic Claude had a deep feeling for art and music. Claude Johnson was undoubtedly the business force which made Rolls-Royce preeminent in the Edwardian period and beyond. His organisational skills were phenomenal. As soon as he had Rolls-Royce on a sound footing he began to seek out artists who could enhance the Rolls-Royce image. He used the great sculptor and typographer Eric Gill in 1906 to design the company’s font. The sculptor Charles Robinson Sykes was invited to design the company’s famous car mascot, the Spirit of Ecstasy, in 1910. -

Chepstow Matters

Telephone 01291 606 900 December 2017 Community Chepstow^ Matters Hand delivered FREE to c10,000 homes across Chepstow & the surrounding villages Christmas is coming ... and there are many ways to join in the local celebrations listed inside this month’s issue. Christmas shopping? Plenty of local businesses with great gift ideas ... see inside for more details! THE PERFECT DESTINATIONFOR 01291635555 YOUR BUSINESS... basepoint.co.uk FLEXIBLE MEETING GREAT Formoreinformation WORKSPACE ROOMS FACILITIES FROM 1PERSON FROM ONLY ON SITE PARKING contactustoday UP TO 250 PEOPLE 15 PERHOUR &24/7ACCESS [email protected] @basepoint_chep INSIDE: • Local People • Local Businesses • Local Community Groups & Events Dear Readers... Christmas is almost upon us and, as I go to print on this edition, we are a week away from switching on Contact Us : the Town’s Christmas lights - our front cover depicts scenes from last year’s event. This is Santa’s first 01291 606 900 opportunity of the year to visit Chepstow, and his other scheduled visits are listed on page 7 - keep a [email protected] look out for his sleigh and give him a wave when he [email protected] visits your area! www.mattersmagazines.co.uk This festive edition of your community magazine is Chepstow Matters jam packed with details of all the local Christmas Editor: Jaci Crocombe fairs, concerts, carol and church services that we c/o Batwell Farm, Shirenewton NP16 6RX had received details of at time of going to print. It Reg Office: Matters Magazines Ltd, also contains plenty of Christmas present ideas to 130 Aztec West, Almondsbury BS32 4UB fulfil your shopping needs - Keep it Local and support Co Regn No: 8490434 our local businesses. -

City Research Online

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by City Research Online City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Bawden, D. ORCID: 0000-0002-0478-6456 (2018). 'In this book-making age': Edward Kemp as writer and communicator of horticultural knowledge. Garden History, 46(Suppl1), This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/20285/ Link to published version: Copyright and reuse: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] david bawden ‘in this book-making age’: edward kemp as writer and communicator of horticultural knowledge Edward Kemp, although best known as a park superintendent and a designer of parks and gardens, was also an influential and best-selling author. His how to lay out a garden, running into several editions, is the best known and most influential of his written works, but there were others, notably editions of the hand-book of gardening and parks, gardens etc. of london and its suburbs, the first ever such regional survey. Kemp assisted Joseph Paxton with the editing of his publications, and was a regular and thoughtful contributor to magazines, most notably the gardeners’ chronicle, where his critiques, such as that of the then new gardens of Biddulph Grange, Staffordshire, received considerable attention. -

Avon Power Station EIA Scoping Report

Avon Power Station EIA Scoping Report Scottish Power Generation Limited Avon Power Station January 2015 EIA Scoping Report Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background 1 Consenting Regime 3 Objectives of Scoping 3 The Need for the Proposed Development 4 2 Description of the Existing Environment 6 Description of the Site 6 Site surroundings 8 Historic and Existing Site Use 9 Sensitive Environmental Receptors 10 Previous Environmental Studies 11 3 Project Description 12 The Proposed Development 12 Overview of Operation of Combined Cycle Gas Turbines 13 Fast Response Generators 15 Electricity Connection 15 Gas Connection 16 Water Supply Options 16 Water Discharge 17 Access to the Site 17 Potential Rail Spur 17 Carbon Capture Readiness (CCR) 17 Preparation of the Site 18 Construction Programme and Management 19 4 Project Alternatives 20 Alternative Sites 20 Alternative Developments 20 Alternative Technologies 21 5 Planning Policy 22 Primary Policy Framework 22 Secondary Policy Framework 23 6 Potentially Significant Environmental Issues 25 Air Quality 25 Noise and Vibration 28 Ecology 31 Flood Risk, Hydrology and Water Resources 35 Geology, Hydrogeology and Land Contamination 36 Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 38 Traffic and Transport 41 Land Use, Recreation and Socio-Economics 43 Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment 44 Health Impact Assessment 47 Sustainability and Climate Change 47 CHP Assessment 48 Avon Power Station January 2015 EIA Scoping Report CCR Assessment 48 7 Non-Significant EIA Issues 49 Waste 49 Electronic Interference 49 -

PWLLMEYRIC Guide Price £425,000

PWLLMEYRIC Guide price £425,000 . www.archerandco.com To book a viewing call 01291 62 62 62 www.archerandco.comwww.archerandco.com To book a viewing call 01291 62 62 62 PRIORY COTTAGE Pwllmeyric, Chepstow, Monmouthshire NP16 6LE . Charming two bedroomed cottage style bungalow Excellent views over open countryside In very popular location with easy access to M48 motorway . A charming two bedroomed cottage style bungalow dating back to c1920's which has been sympathetically extended, updated and improved over recent years to provide spacious and versatile accommodation situated in the popular village of Pwllmeyric which is located just over one mile to Chepstow Town Centre, which provides primary and senior schools, leisure centre, shops, pubs, restaurants, bus and rail links, approximately 1.5 miles to the M48 Severn Bridge providing excellent commuting to Newport, Cardiff, Bristol, Gloucester and London. Just along the road is the famous St Pierre Golf and Country Club, Chepstow Garden Centre and for those who enjoy walking St Pierre Woods and a variety of countryside walks over open farmland. Mathern is the next village along to Pwllmeyric and boasts its own Gastro Pub, Mathern Palace and the beautiful and ancient St Tewdrics Church dating back to 600 AD. Also within a short driving distance is the beautiful and renowned Wye Valley and Offas Dyke Path which runs along the Welsh and English Border both of which provide a wealth of outdoor pursuits including walking, climbing, cycling and riding, Chepstow and Caldicot Castles and the Cistercian Abbey at Tintern provide places of historical interest locally and also hold occasional seasonal open air entertainment.