Donald A. Kruse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Becoming Latin American Canadian

In-Between Cultures: Becoming Latin American Canadian by Josue Tario A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Social Justice Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Josue Tario, 2017 In-Between Cultures: Becoming Latin American Canadian Josue Tario Master of Arts Social Justice Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2017 Abstract Rooted in my own experiences and extending to phenomenological interviews with seven Latin American Canadian youth between the ages of 18 and 29 in the Greater Toronto Area, this thesis examines how the dominant educational and cultural narratives shape the heterogeneous ways in which they perceive themselves and others. Findings show that such narratives engender a sense of in-betweenness among Latin American Canadian youth that both inhibit and empower them in pursuing self-fulfillment. This study juxtaposes these findings to feminist pedagogies of “third space” and “critical spirituality” which have the ability to enhance the educational experiences of not just Latin American Canadian students but all participants in education. The overarching objective of this thesis, however, transcends the case study and explores the intersections between discourse, identity formation and agency, proposing critical spirituality as a practice enabling agency and as a transformational “punctum” that embraces the process of becoming over being. ii Acknowledgments I would like to sincerely thank my thesis supervisor, Dr. Miglena Todorova. Her patience and instruction were imperative for this project to be completed. Along with her theoretical insight and pedagogical awareness, the emotional and spiritual support she provided throughout the entire process was immensely pivotal for me to keep going. -

A Cultural Competence Guide for Primary Health Care Professionals in Nova Scotia

A Cultural Competence Guide for Primary Health Care Professionals in Nova Scotia “Adding wings to caterpillars does not create butterflies--it creates awkward and dysfunctional caterpillars. Butterflies are created through transformation...” Stephanie Marshal 2005 PROMOTING CULTURAL COMPETENCE IN PRMARY HEALTH CARE A Cultural Competence Guide for Primary Health Care Professionals in Nova Scotia Table of Contents Preface Section I General Information • Cultural Competence • Key Concepts • 8 Elements of Cultural Competence • Diverse Communities in Nova Scotia Section II Tools for Primary Health Care Providers • Providing Health Care in a Multicultural Society • Patient and Client Encounter Questions • LIAASE: A General Cultural Competence Tool • Health Professional Self-Assessment Tool Section III Tools for Management and Administrative Staff in Primary Health Care Settings • An Organizational Change Strategy • Organizational Assessment Tool • LIAASE: A General Cultural Competence Tool • Health Professional Self-Assessment Tool Section IV Tools for Front-Line Staff in Primary Health Care Settings • Addressing Conflict • LIAASE: A General Cultural Competence Tool • Health Professional Self-Assessment Tool Section V Additional Resources • Community and Organizational Contact Information • Online Resources • Definition of Terms Appendix A – Diverse Communities of Nova Scotia - Graphs Appendix B – Diversity and Social Inclusion in Primary Health Care Initiative Appendix C – “Bridging the Gap: Bringing Together Culture and Health Care” Appendix D – Culture Competence and the Primary Care Provider by Ardys McNaughton Dunn References PROMOTING CULTURAL COMPETENCE IN PRMARY HEALTH CARE Acknowledgements The information in this guide was collated from a variety of sources. Information about Nova Scotia’s diverse communities, and the barriers diverse communities face in accessing primary health care services, was gathered through a series of consultative workshops held by the Department of Health and each District Health Authority in Nova Scotia. -

Citizenship Revocation in the Mainstream Press: a Case of Re-Ethni- Cization?

CITIZENSHIP REVOCATION IN THE MAINSTREAM PRESS: A CASE OF RE-ETHNI- CIZATION? ELKE WINTER IVANA PREVISIC Abstract. Under the original version of the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act (2014), dual citizens having committed high treason, terrorism or espionage could lose their Canadian citizenship. In this paper, we examine how the measure was dis- cussed in Canada’s mainstream newspapers. We ask: who/what is seen as the target of citizenship revocation? What does this tell us about the direction that Canadian citizenship is moving towards? Our findings show that Canadian newspapers were more often critical than supportive of the citizenship revocation provision. However, the press ignored the involvement of non-Muslim, white, Western-origin Canadians in terrorist acts and interpreted the measure as one that was mostly affecting Canadian Muslims. Thus, despite advocating for equal citizenship in principle, in their writing and reporting practice, Canadian newspapers constructed Canadian Muslims as sus- picious and less Canadian nonetheless. Keywords: Muslim Canadians; Citizenship; Terrorism; Canada; Revocation Résumé: Au sein de la version originale de la Loi renforçant la citoyenneté cana- dienne (2014), les citoyens canadiens ayant une double citoyenneté et ayant été condamnés pour haute trahison, pour terrorisme ou pour espionnage, auraient pu se faire révoquer leur citoyenneté canadienne. Dans cet article, nous étudions comment ce projet de loi fut discuté au sein de la presse canadienne. Nous cherchons à répondre à deux questions: Qui/quoi est perçu comme pouvant faire l’objet d’une révocation de citoyenneté? En quoi cela nous informe-t-il sur les orientations futures de la citoy- enneté canadienne? Nos résultats démontrent que les journaux canadiens sont plus critiques à l’égard de la révocation de la citoyenneté que positionnés en sa faveur. -

Exploring Young Black/ African Canadian Women's Practices

Exploring Young Black/ African Canadian Women’s Practices of Engagement and Resistance: Towards an Anticolonial Solidarity Building by Thashika Pillay A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in SOCIAL JUSTICE AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES IN EDUCATION Department of Educational Policy Studies University of Alberta © Thashika Pillay, 2018 ii Abstract The experiences of young women of Black/ African descent living in Edmonton/ Amiskwaciwaskahikan – in what is currently Canada – are mediated by relations and structures of power as constructed through settler colonialism, patriarchy, capitalism, imperialism, and neoliberalism. These political, economic, social, and cultural structures and systems organize the world and influence young women’s responses, both as individuals and as collectives. Young women of African descent are also influenced by African Indigenous Knowledge Systems (AIKS), a philosophy rooted in a relational worldview and culture in which knowledge is collectively and community oriented. A critical analysis of these interlocking structures and worldviews is integral to understanding the process through which the emergence and formation of subjects and selves as well as the collective occurs. This study is positioned within an Indigenous hermeneutics and draws on the work of Manulani Aluli Meyer as well as Desmond Tutu’s conceptualization of Ubuntu. Using a critical qualitative research design that included focus group and semi-structured interviews with nine young women -

Taking Root: Media, Community, and Belonging in Ottawa April Bella

Taking Root: Media, Community, and Belonging in Ottawa April Bella Lilas Carriere A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy in Political Science School of Political Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © April Bella Lilas Carriere, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 For my grand-mother, Lili, who, through her love, support, and indomitable spirit, instilled in me everything I needed to follow my dreams II TABLE OF CONTENTS Legend ........................................................................................................................................ VI Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... VII Preface ..................................................................................................................................... VIII Chapter 1 – Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Guiding Research Questions and Hypothesis ............................................................................. 5 Thesis Outline.............................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 2 – Literature Review, theoretical framework, and Methodology ................................... 8 Literature Review ....................................................................................................................... -

Racism in All Forms and Denounce Social, Economic, and Educational Inequities to Which Ethnocultural Groups Are Subject

MINUTES - LDRRAC Education Committee - August 13, 2015, at 10:00 a.m, London Public Library Downtown In Attendance:- Ian Silver, Chair; Jessica Hill; Michelle Lynne Goodfellow; Shirley Honyust. Regrets: Chad Callander; Suzanne Morrison ; Fae Andrighetti 1. Website a. Michelle will discuss the potential website with Jackie Martin, and report back to the subcommittee 2. Diversity Definitions a. We have obtained permission from the Halifax School Board to use their definitions, as attached. b. To replace the Nova Scotia First Nations terms used in the document, Jessica has prepared the attached glossary of local First Nations Terms 3. Two databases are attached – the Database of Cultural and Ethnic Groups is excerpted from the Website of Information London, with the addition of weblinks, where available. In addition, rthe list of religious and cultural clubs at Western University is attached, excerpted from the WUUCC Website. 4. The subcommittee will review the LGBTQTT definitions, and report after the next meeting. 5. Reception for the Awards Ceremony a. Quotes will be requested from Steeltown Catering and the City Hall caterer, and provided at the LDRRAC meeting, to a maximum of $600 b. Two members of the Board of Trustees of the Canadian Human Rights Museum are located in Toronto. We will contact both, to see if either would be available to give a brief talk at the receptions. Those names are appended. We would recommend paying reasonable transportation costs, to a maximum of $200. 6. At Shirley’s request, a copy of our existing brochure is attached. a. The subcommittee is recommending these be translated into Oneida and Ojibwa, to a total cost not to exceed $300 Respectfully submitted, Ian Silver m Home b About the HRSB b Board Services b Diversity Management Diversity Definitions The following definitions of terms are provided to assist users with the general understanding of issues related to diversity management. -

Our Immigration Saga: Canada@150

SPRING 2017 Our Immigration Saga: Canada@150 In collaboration with RANDY BOSWELL MADELINE ZINIAK DORA NIPP VICTOR ARMONY MONICA MACDONALD LINTON GARNER TIMOTHY J. STANLEY FARID ROHANI JACK JEDWAB MYER SIEMIATYCKI STEVE SCHWINGHAMER MORTON WEINFELD AVVY GO RATNA GHOSH TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 INTRODUCTION IMMIGRANTS’ STORIES OF SETBACKS AND RESILIENCE KEEP REWRITING — AND ENRICHING — OUR NATIONAL NARRATIVE Randy Boswell 9 WHY DO WE NEED A MUSEUM OF IMMIGRATION? Monica MacDonald 13 MIGRATION IS AN ESSENTIAL PART OF CANADA’S HISTORICAL NARRATIVE Jack Jedwab 18 THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE LUCKY: IMMIGRATION AND THE CANADIAN EXPERIENCE Morton Weinfeld 22 ETHNIC MEDIA IN CANADA: THE POWER OF REFLECTION; A LINK TO NATION BUILDING AND IDENTITY Madeline Ziniak 26 HISTORICAL ISSUES AROUND BLACK IMMIGRATION TO CANADA AND HOW THEY HAVE AFFECTED THE BLACK COMMUNITY Linton Garner 31 CANADA 150: THE JEWISH IMPRINT Myer Siemiatycki 35 SHADES OF IMMIGRATION PAST: THE EXPERIENCE OF CHINESE IMMIGRANTS Avvy Go & Dora Nipp 40 THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF CHINESE IMMIGRANTS TO CANADIAN SOCIETY Timothy J. Stanley 44 “THIS IS TICKLISH BUSINESS”: UNDESIRABLE RELIGIOUS GROUPS AND CANADIAN IMMIGRATION AFTER THE SECOND WORLD WAR Steven Schwinghamer 53 SOUTH ASIAN IMMIGRATION TO CANADA Ratna Ghosh 57 SETTLING NORTH OF THE U.S. BORDER: CANADA’S LATINOS AND THE PARTICULAR CASE OF QUÉBEC Victor Armony 62 LEAVING A LAND WITH LIMITS AND TAKING OWNERSHIP OF AN ADOPTED NATION Farid Rohani CANADIAN ISSUES IS PUBLISHED BY ASSOCIATION FOR CANADIAN STUDIES BOARD OF DIRECTORS Canadian Issues is a quarterly publication of the Association THE HONOURABLE HERBERT MARX Montréal, Québec, acting Chair of the Board for Canadian Studies (ACS). -

Explaining Intentions to Seek Mental Health Services Among Black Canadians

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 7-19-2018 Explaining Intentions to Seek Mental Health Services among Black Canadians Renee Taylor University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Taylor, Renee, "Explaining Intentions to Seek Mental Health Services among Black Canadians" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 7579. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/7579 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. Explaining Intentions to Seek Mental Health Services among Black Canadians By Renee E. Taylor A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of Psychology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2018 © 2018 Renee Taylor Explaining Intentions to Seek Mental Health Services among Black Canadians by Renee E. -

Labour Force Survey, August 2020 Released at 8:30 A.M

Labour Force Survey, August 2020 Released at 8:30 a.m. Eastern time in The Daily, Friday, September 4, 2020 Context: COVID-19 restrictions continue to ease The August Labour Force Survey (LFS) results reflect labour market conditions as of the week of August 9 to 15, five months following the onset of the COVID-19 economic shutdown. By mid-August, public health restrictions had substantially eased across the country and more businesses and workplaces had re-opened. Assessing the labour market as lifting of COVID-19 restrictions continues This LFS release continues to integrate the international standard concepts such as employment and unemployment with supplementary indicators that help to monitor the labour market as restrictions are lifted and capture the full scope of the impacts of COVID-19. A series of survey enhancements were continued in August, including supplementary questions on working from home, workplace adaptations and financial capacity. New questions were added on concerns related to returning to usual workplaces and receipt of federal COVID-19 support payments. This release also includes, for the second time, information on the labour market conditions of population groups designated as visible minorities. Through the addition of a new survey question and the introduction of new statistical methods, the LFS is now able to more fully determine the impact of the COVID-19 economic shutdown on diverse groups of Canadians. Data from the LFS are based on a sample of more than 50,000 households. Statistics Canada continued to protect the health and safety of Canadians in August by adjusting the processes involved in survey operations. -

U of L Oral History Project Commemorates Alberta's African

For immediate release — Tuesday, February 20, 2018 U of L oral history project commemorates Alberta’s African- American settlers After more than a year in the making, a film documenting the lives of black settlers in Alberta and Saskatchewan and their experiences with discrimination will premiere in Edmonton during Black History Month. We are the Roots: Black Settlers and Their Experiences of Discrimination on the Canadian Prairies was the brainchild of Deborah Dobbins, president of Edmonton’s Shiloh Centre for Multicultural Roots (SCMR). After securing funding from the Alberta Human Rights Commission, she teamed up with Drs. Jenna Bailey and David Este. Bailey is an adjunct history professor and senior research fellow at the University of Lethbridge’s Centre for Oral History and Tradition (COHT). Este is a professor in the Faculty of Social Work at the University of Calgary. “Here we are 18 months later and it has been amazing,” says Dobbins. “The people we interviewed told wonderful stories and their experiences focus on the positive, but there’s lots of adversity, too. Through it all, we’re here and able to celebrate our accomplishments.” Bailey and Este interviewed 19 second- and third-generation individuals from the families of the original settlers who left the United States to come to Western Canada between 1905 and 1912. Between 1,000 and 1,500 African Americans came to Canada, largely settling in the small rural Alberta communities of Amber Valley, Campsie, Wildwood, Breton and Maidstone in Saskatchewan. “It’s a fascinating history,” says Bailey. “I learned a lot about discrimination in Alberta. -

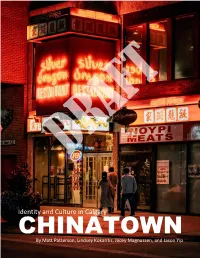

Identity and Culture in Calgary's Chinatown

Identity and Culture in Calgary CHINATOWN By Matt Patterson, Lindsey Kokaritis, Jacey Magnussen, and Jason Yip DRAFT VERSION – PLEASE DO NOT CIRCULATE TERRITORIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report focuses on an area on the south banks of the Bow River that is currently known as Chinatown and, in part, examines the development of this neighbourhood within the larger context of European colonialization and settlement. The City of Calgary must be recognized as being situated within the traditional territories of the Blackfoot and the people of the Treaty 7 region in Southern Alberta, which includes the Siksika, the Piikuni, the Kainai, the Tsuut’ina, and the Stoney Nakoda First Nations, including Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley First Nation. Chinatown, distinctly, sits near the intersection of the Bow and Elbow Rivers and the traditional Blackfoot name of this place is “Mohkinstsis”. The City of Calgary, is also home to Métis Nation of Alberta, Region III. i DRAFT VERSION – PLEASE DO NOT CIRCULATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was made possible with the support and contributions of dozens of people. The research for this report was supported by a grant provided by the City of Calgary. We would like to thank our partners at the City of Calgary, Janet Lavoie (Arts & Culture) and Fazeel Elahi (Community Planning, Planning & Development) who provided guidance and direction. We would also like to thank Professor Eliot Tretter (Geography, University of Calgary) who served as co-investigator on the grant, helped to oversee the research, and provided helpful feedback on the final report. As well, this partnership was made possible by the Urban Alliance, a partnership established by the City of Calgary and the University of Calgary to facilitate research collaboration. -

Canada's Latinos and the Particular Case of Québec

lasaforum fall 2015 : volume xlvi : issue 4 DEBATES: GLOBAL LATIN(O) AMERICANOS Settling North of the U.S. Border: Canada’s Latinos and the Particular Case of Québec by VICTOR ARMONY | Université du Québec à Montréal | [email protected] The case of Latin American Canadians 1970s and the 1990s, most immigrants If we take the narrowest definition possible offers an exceptional opportunity to from Latin America came to Canada for and consider a Latin American to be any examine and compare how minorities are political reasons (i.e., fleeing military person born in a Latin American country constructed and transformed in different dictatorships in South America and civil (that is, a first-generation immigrant), we host societies. Minorities are shaped wars in Central America). However, since see that this group represents just about 6 differently by their societal context, and the 1990s, and even more clearly during percent of all immigrants in Canada. Canada is especially relevant in that regard the following decades, most Latin However, its growth rate is roughly three because of the existence of two main Americans in Canada have been admitted times higher than that of the overall dominant cultural environments— under the “economic category”: 70 percent immigrant population (32 vs. 10 percent grounded on political and territorial in 2012. This means, in general terms, that between 1996 and 2001; 47 vs. 12.7 configurations—within the same country: they have been granted permanent percent between 2001 and 2006; 49 vs. an English-language Canadian majority at residency on account of their prospective 12.9 percent between 2006 and 2011), due the national level and a French-language employability as skilled workers in Canada, to the increasing share of Latin American Québécois majority in Canada’s second a condition evaluated on the basis of their newcomers, most of them having arrived most-populated province.