The Vulnerability of Subsea Infrastructure to Underwater Attack: Legal Shortcomings and the Way Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High-Speed Broadband Submarine Cable FLY-LION3 Makes Landfall in Mayotte

Press Release Mamoudzou (Mayotte), 25 February 2019 High-speed broadband submarine cable FLY-LION3 makes landfall in Mayotte Orange and the members of the FLY-LION3 (Lower Indian Ocean Network) consortium - the Société Réunionnaise du Radiotéléphonie and Comores Câbles - have completed the deployment of a new fibre-optic submarine cable connecting Moroni (Grande Comore) and Mamoudzou (Mayotte). The cable, which is scheduled to be activated in the third quarter of 2019, made landfall in Mamoudzou today. The 400 km-long FLY-LION3 cable will enhance the connectivity in the Indian Ocean by opening a new route to connect Mayotte to the global internet and a direct connection to Grande Comore. Orange Marine, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Orange group, is responsible for laying the cable. Diversification and security With landing stations in Kaweni (Mamoudzou) and Moroni, FLY- LION3 provides new diversification solutions for submarine telecommunications infrastructure and provides greater security in the event of outages in the zone. FLY-LION3 will also link to existing cables LION2 and EASSy, offering a direct connection to the east coast of Africa. The FLY-LION3 cable benefits from 1 wavelength division multiplexing technology, which enables each fibre pair to reach a maximum capacity of 20x100Gbps. The cable includes two pairs of fibres making for a total capacity of 4 terabits per second. FLY-LION3 will support the development of high-speed broadband internet in both regions for many years to come. Powerful networks for every region For many years, Orange has helped to improve connectivity in the Indian Ocean by participating and investing in several submarine cable projects: . -

ITU-Dstudygroups

ITU-D Study Groups Study period 2018-2021 Broadband development and connectivity solutions for rural and Question 5/1 Telecommunications/ remote areas ICTs for rural and remote areas Executive summary This annual deliverable reviews major backbone telecommunication Annual deliverable infrastructure installation efforts and approaches to last-mile connectivity, 2019-2020 describes current trends in last-mile connectivity and policy interventions and recommended last-mile technologies for use in rural and remote areas, as well as in small island developing States (SIDS). Discussions and contributions made during a workshop on broadband development in rural areas, held in September 2019, have been included in this document, which concludes with two sets of high-level recommendations for regulators and policy-makers, and for operators to use as guidelines for connecting rural and remote communities. 1 More information on ITU-D study groups: E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: +41 22 730 5999 Web: www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/study-groups ITU -D Study Groups Contents Executive summary 1 Introduction 3 Trends in telecommunication/ICT backbone infrastructure 4 Last mile-connectivity 5 Trends in last-mile connectivity 6 Business regulatory models and policies 7 Recommendations and guidelines for regulators and policy-makers 8 Recommendations and guidelines for operators 9 Annex 1: Map of the global submarine cable network 11 Annex 2: Listing of submarine cables (A-Y) 12 2 More information on ITU-D study groups: E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: +41 22 730 5999 Web: www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/study-groups ITU -D Study Groups Introduction The telecommunications/ICT sector and technologies have evolved over a long period of time, starting with ancient communication systems such as drum beating and smoke signals to the electric telegraph, the fixed telephone, radio and television, transistors, video telephony and satellite. -

Regional Systems

SubmarineTelecomsFORUM REGIONAL SYSTEMS An international forum for the expression of ideas and opinions Issue 20 Issue 17 pertaining to the submarine telecoms industry May 2005 January 2005 1 Submarine Telecoms Forum is published bi-monthly by WFN Strategies, L.L.C. The publication may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form, in whole or in part, without the permission of the publishers. ExordiumWelcome to the 20th edition of Submarine Telecoms Forum, our Regional Systems issue. Submarine Telecoms Forum is an independent com- We are approximately 14 months from the previous SubOptic and only 24 months from the mercial publication, serving as a freely accessible forum for next! Whether that latter fact produces an air of excitement is certainly debatable, but I look professionals in industries connected with submarine optical forward to the next conference with far less trepidation than the last. fibre technologies and techniques. Liability: while every care is taken in preparation of this As I discussed with a GIS colleague recently, it is really nice to be drawing lines on a chart publication, the publishers cannot be held responsible for the again; even short lines are better than none of late. And while it’s still not time to cash in one’s stock, it is time to work again on some real projects. And those, even small, are a start. accuracy of the information herein, or any errors which may occur in advertising or editorial content, or any consequence arising from any errors or omissions. This issue brings some exciting articles together for your consideration. The publisher cannot be held responsible for any views Brian Crawford of Trans Caribbean Cable Company gives his view of the world in this issue’s expressed by contributors, and the editor reserves the right installment of Executive Forum. -

Strategies for the Promotion of Broadband Services and Infrastructure: a Case Study on Mauritius

MDG # broadband series millennium development goals 8 partnership REGULATORY & MARKET ENVIRONMENT International Telecommunication Union Place des Nations Strategies for the promotion of CH-1211 Geneva 20 Switzerland broadband services and infrastructure: www.itu.int A CASE STUDY ON MAURITIUS BROADBAND SERIES Printed in Switzerland Geneva, 2012 08/2012 Strategies for the promotion of broadband services and infrastructure: a case study on Mauritius This report has been prepared for the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) by Sofie Maddens- Toscano. This study was funded by the ITU and the Broadband Commission for Digital Development. We would especially like to thank Dr K. Oolun, Executive Director, Information and Communications Technologies Authority for his invaluable support. It is part of a new series of ITU reports on broadband that are available online and free of charge at the Broadband Commission website: http://www.broadbandcommission.org/ and at the ITU Universe of Broadband portal: www.itu.int/broadband. Please consider the environment before printing this report. © ITU 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any means whatsoever, without the prior written permission of ITU. Strategies for the promotion of broadband services and infrastructure: a case study on Mauritius Table of Contents Page Preface ........................................................................................................................................ iii Foreword ................................................................................................................................... -

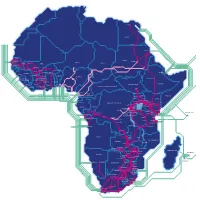

African International Capacity Demand, Supply and Economics in an Era of Bandwidth Abundance

The Future of African Bandwidth Markets African International Capacity Demand, Supply and Economics in an Era of Bandwidth Abundance A XALAM ANALYTICS INVESTOR REPORT May 2017 Our analysis goes deeper. For we know no other way. Xalam. Xalam Analytics, LLC Part of the Light Reading Research Network 1 Mifflin Place, Harvard Sq., Suite 400, Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Copyright 2017 by Xalam Analytics, LLC. All rights reserved. Please see important disclosures at the end of this document. We welcome all feedback on our research. Please email feedback to: [email protected] © Xalam Analytics LLC - 2017 2 About this Report The Xalam Analytics reports offer our take on key strategic and tactical questions facing market players in the markets we cover. They leverage continuous primary and secondary research and our Africa digital infrastructure, services and applications forecast models. Our general objective is to provide our customers with alternative, independent views of the forces driving the marketplace, along with a view on outlook and value. We purposefully refer to our reports as “Investor Reports”, though we do not provide stock recommendations. This, we believe, emphasizes the general focus of our analysis on economic value – from an investor’s perspective. The insights in this reports are our views, and our views only. Some of the elements are speculative and/or scenario-based. This report follows a format purposefully designed to be easy to read, with a style that aims to be straightforward, while adding value. We are obsessed with not wasting our customers’ time, and providing them with commensurate value for the investment they are making in our content. -

LIT Fibre Map May21

CAIRO EGYPT AAE-1 Argeen EiG SEAMEWE-5 Port Sudan SEACOM SEAMEWE-4 EASSy Dahra PEACE SUDAN SENEGAL KHARTOUM NIGER DAKAR Kidira Kayes CHAD MALI Kaolack Tambacounda BAMAKO Al Junaynah El Obeid Kita N’DJAMENA Metema OUAGADOUGOU Bobo-Dioulasso Kano Sikasso Mongo BURKINA FASO Nyala DJIBOUTI GUINEA CONAKRY Ferkessedougou BENIN NIGERIA FREETOWN ADDIS ABABA Ouangolodougou ABUJA SIERRA LEONE COTE D’IVOIRE Bondoukou TOGO Bouake PORTO- ETHIOPIA MONROVIA Lagos SOUTH SUDAN GHANA LOME NOVO CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC LIBERIA YAMOUSSOUKRO ACCRA Abidjan Port JUBA Harcourt DOUALA Yaounde Nimule Moyale WACS NCSCS CAMEROON Kribi UGANDA SOMALIA SAT3 Karuma ACE Masindi Mbale Equiano KENYA 2Africa Tororo Bungoma SAIL KAMPALA LIBREVILLE Eldoret Liboi DEM. REP. OF CONGO Masaka Busia Meru Mbarara Nakuru Kisumu Goma Kagitumba Garissa NAIROBI GABON CONGO Gatuna Thika Lamu RWANDA KIGALI TEAMS Bukavu DARE Kindu Rusumo Mwanza Rusizi Malindi BRAZZAVILLE Namanga Kabanga Moshi PEACE KINSHASA Bujumbura SEYCHELLES Arusha Pointe Noire Kasongo Shinyanga Mombasa Manyovu Kikwit BURUNDI LION 2/LION Kananga Singida Tanga Inga Muanda Mbuji-Mayi SEAS DODOMA Morogoro Mwene-Ditu Dar es Salaam Iringa Tunduma LUANDA SACS TANZANIA Kolwezi Lubumbashi Solwezi ANGOLA Kitwe Chipata Ndola MOZAMBIQUE ZAMBIA MALAWI LUSAKA Chirundu Livingstone Kariba Bindura Nyamapanda Sesheke Kasane MADAGASCAR ZIMBABWE HARARE Nyanga Victoria Falls Gweru MAURITIUS Mutare NAMIBIA Bulawayo Plumtree Masvingo Zvishavane Francistown Phokoje REUNION Walvis Bay WINDHOEK Beitbridge BOTSWANA Morupule Tzaneen Polokwane GABORONE Equiano Komatipoort Lobatse MAPUTO Johannesburg PRETORIA 2Africa ESWATINI SOUTH AFRICA Kimberley Bloemfontein Richards Bay MASERU EASSy LESOTHO Mtunzini Durban SEACOM Umbogintwini SAT3 METISS WACS Beaufort West SAFE ACE Yzerfontein Port Elizabeth Cape Town. -

Global WAN Solutions Managed Global MPLS VPN Service

Global WAN Solutions Managed Global MPLS VPN Service 23-03-2016 Managed Global MPLS VPN Service Mauritius Telecom’s Managed Global MPLS VPN Service is an international virtual private network solution based on IP/MPLS (Multi- anddata on a single network. Our Global MPLS VPN service is built on resilient network architecture with Network to Network Interface (NNI) Interconnection with global MPLS Partners at MT’s Points of Presence (PoP) in Telehouse 1, Paris and Telehouse West, London. MT has also implemented an MPLS network with Partners in Asia, Africa and the Indian Ocean Islands of Seychelles and Madagascar. Partner’s MPLS Network - Europe, North America MT POP London Partner’s MPLS North Route 2 Network - Asia LION/SEACOM MT POP Paris West Route 1 SAFE/WAGS North Route LION/EASSY/EIG West Route 2 SAFE/TYCO East Route SAFE Partners’ MPLS Network - Africa LION/EASSY/SEAS SAFE : South Africa Far East SAT-3 : South Atlantic Telecommunications cable MT’s IP/MPLS Network LION WASC : West African Submarine Cable LION : Lower Indian Ocean Network EASSY : Eastern Africa Submarine Cable System South Route SAFE EIG : Europe India Gateway WACS : West Africa Cable System SEACOM: Cable on East coast of Africa • A one stop shop solution with Single point of contact for • End to end service management ordering, billing and fault management • • Highest network reliability with auto-protected submarine performance and line status online through secured web cable paths access • Managed Services with Advanced SLA Options for faster site • Layer 2 and -

Carrier Services Solutions Telkom

Telkom Carrier Services Solutons Monitoring Fully managed network and advanced ant-fraud systems Flexibility Antcipaton Adaptable solutons and Prepared for data explosion with efficient voice organisaton IP investment and innovaton Commitment Large investments in fast-growing markets: Africa and the Middle East Who we are Telkom carrier services offers innovatve solutons coupled with expertse, a high level of service management and global reach on an expansive and reliable network. Through our superior infrastructure and global partnerships, we are able to offer highly compettve rates for our services. We have extensive experience in the provision of end-to-end, wholesale and carrier services across Kenya, throughout Africa and globally. Who we serve Our clientele ranges from ISP’s, Mobile Network Operators, Multnatonal Corporatons, OTTs and Global Integraton Companies. Over the years, we have matured within the industry to become a market leader in carrier service provisions. Through our resources and partnerships, we provide reliable service offerings to our clients and have positoned ourselves as the regional carrier of choice. Global Carriers Mobile Network Operators ISP’s OTT’s Global Integraton Companies www.telkom.co.ke What can we do for you? We offer services that meet our customers' needs; whether they require turnkey solutons or a fully customized approach for Voice, IP Transit, Capacity and Data Center Services. This allows our customers to concentrate on providing their own customers with the solutons they are looking for. Our Mission Providing the best value for a simpler life, efficient business and stronger communites. Our Voice Solutons 1. Hubbing 3. Kenya terminatng Our service provides you with internatonal voice traffic terminaton. -

© M-Imagephotography

Digital Africa © m-imagephotography Digital technology is not only key to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals, it also supports our own ambitious commitments at Orange Middle East and Africa in terms of environmental responsibility and digital inclusion. That’s why we have identified the six main Goals where we feel we can have the greatest impact. Together let’s work to build a more responsible, sustainable world. Contents “ Our vision for Africa by Alioune Ndiaye ................................................................................ 3 1 How digital technology accelerates Africa’s integration and development ..... 4-7 2 Orange’s international interconnection network: spotlight on Africa ............. 8-9 3 Connecting Africa to the entire world .............................................................................. 10-13 4 Boosting digital inclusion in Africa ......................................................................................14-17 5 Digital tools for socio-economic development and employment ...................18-21 6 How digital services drive inclusion and development ......................................... 22-25 2 Back to contents The education divide experienced by women and rural populations will have gradually been reduced. There will be countless innovative digital solutions designed to meet the needs of African people. State services will be more relevant, easier to use, and better targeted thanks to digitalization, data, and artificial intelligence. And because improved access is closely linked to economic growth, increased connectivity will greatly contribute to the continent’s prosperity because it facilitates business and government activities. To tackle the climate emergency, Africa will have embraced these digital transitions in an eco- friendly way by increasing the use of renewable energies and reducing waste. At Orange Middle East and Africa, we firmly believe that this dream is within our grasp, and so we’re investing €1 billion every year on the continent to help achieve it. -

Submarine Telecoms

SUBMARINE TELECOMS FORUMISSUE 111 | MARCH 2020 FINANCE & LEGAL EXORDIUM FROM THE PUBLISHER WELCOME TO ISSUE 111, OUR FINANCE & LEGAL EDITION f ever there was a need for connectivity, Maybe this is the time to perfect virtual it is today… conferences. From my vantage along the Poto- But on the flipside, I read an article re- mac River the news has been coming cently saying if everyone stayed home, we like a slow moving, yet unstoppable would “break” the internet. Wow, really? I Itrain. Contingency plans have been know I play too much Team Fortress as it prepared and revised. Supplies have been is, but I doubt my supposed increase will purchased and stored, ready for use if shatter anything. absolutely necessary. Yet as an industry we are still incredibly We have already experienced a single busy, adapting to new, challenging rules wave of chest colds through the office, for fielding personnel and assets, but still which is typical this time of year, and getting the job done. have decided, if it comes to it, that we can all work remotely. Half of our people Q&A WITH BERMUDA are located somewhere else anyway; This issue we are talking trends with so, we can simply Skype or Webex or Bermuda’s Deputy Premier and Minister of whatever each other for various project Home Affairs, and gaining an understand- or marketing or planning meetings, and ing of the island’s new legal framework and bank the travel budget for now. I was on a video future plans for submarine cables. Bermuda I was on a video telecon the other day telecon the other is looking to establish itself as a landing with two international locations and was hub for transatlantic submarine cables; so, struck how the general consensus was day with two this is certainly a very interesting read. -

Mauritius Telecom Annual Report 2011

Evolution is not a force but a process. Not a cause but a law. John Morley MAJOR LANDMARKS • First telephone installed in Mauritius and fi rst manual exchange inaugurated • Mauritius connected to Zanzibar and Seychelles by telegraph submarine cable 1883 - 1900 • Durban connected to Mauritius, Rodrigues and Seychelles by second submarine cable • First automatic telephone exchange opened • Telex service introduced • Digital E10B telephone exchange installed 1901 - 1999 • Internet Services launched commercially by Telecom Plus • Mobile GSM services introduced commercially by Cellplus Mobile Communications • Strategic equity partnership with France Telecom signed in November 2000 • SAFE fi bre-optic cable system inaugurated 2000 - 2004 • First Teleshop launched in Curepipe • Wi-Fi offered by Telecom Plus commercially • Cellplus’ 3G Network launched • My.T, Mauritius Telecom’s Multiplay-IPTV services, launched 2005 - 2012 • ADSL launched in Rodrigues • The LION submarine cable came into service in November 2009 OUR CORE VALUES OUR VISION Innovation & Creativity, To be a Premier World Class Quality, Professionalism, Infocom Services Provider Customer Service, Competitiveness 4 MAURITIUS TELECOM - ANNUAL REPORT 2011 CONTENTS Financial Highlights 6 Certifi cate by Company Secretary 8 Corporate Profi le 11 Board of Directors 13 Chairman’s Statement 18 Chief Executive Offi cer’s Review 20 Strategic Executive Committee 25 Corporate Governance 27 Directors’ Annual Report 35 Highlights 2011 41 Business Review 47 Independent Auditor’s Report 64 Statements -

Expanding Regional Connectivity in Asia and the Pacific

Expanding Regional Connectivity in Asia and the Pacific: I. Broadband Markets: State-of-Play II. International Network Vulnerabilities III. Terrestrial Infrastructure Initiatives, Opportunities, and Challenges Michael Ruddy Director of International Research Terabit Consulting www.terabitconsulting.com Part 1: Broadband State of Play in Hub Markets www.terabitconsulting.com Broadband State of Play in 5 “Hub” Markets ESCAP Subregion Market East and Northeast Asia China South and Southwest Asia India North and Central Asia Russia The Pacific Australia Southeast Asia Singapore www.terabitconsulting.com China • China shows the strongest prospects for growth in the region – China is already the world’s largest broadband market, having surpassed the US in 2008 – Currently 10x more fixed-broadband subscribers than India – Fixed-broadband subscribers will exceed 200 million by 2014 – 1.4 Tbps of international demand as of year-end 2011 • In terms of international bandwidth demand, still trailing Japan (>2 Tbps) for the time being www.terabitconsulting.com China: Broadband Targets • 12th Five-Year Plan calls for broadband speeds to increase to 20 Mbps in urban areas and 4 Mbps in rural areas by the end of 2015 – More than 8m fiber kilometers deployed; robust FTTx market of 25m+ (although DSL still dominant) • Ministry of Industry and Information Technology indicated intention to lower broadband access pricing • ARPU of US$11 per month, while comparatively low, should still allow for investment in 4G networks www.terabitconsulting.com India • Extremely promising broadband growth, but timing uncertain • 3G service launch was marred by weak coverage, incompatible handsets, and “bill shock” – Watching 1-hour sporting event on 3G = 300 INR ($5) • Reliance planning nationwide $10 bil 4G rollout – But some foreign 3G/4G investors have pulled out of market, citing “regulatory uncertainty” • Fixed-broadband market: 100Mbps VPON FTTH service launched in 2011 – However, affordable packages were limited to 2Mbps (and 8GB/mo).