Der Fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

05-11-2019 Gotter Eve.Indd

Synopsis Prologue Mythical times. At night in the mountains, the three Norns, daughters of Erda, weave the rope of destiny. They tell how Wotan ordered the World Ash Tree, from which his spear was once cut, to be felled and its wood piled around Valhalla. The burning of the pyre will mark the end of the old order. Suddenly, the rope breaks. Their wisdom ended, the Norns descend into the earth. Dawn breaks on the Valkyries’ rock, and Siegfried and Brünnhilde emerge. Having cast protective spells on Siegfried, Brünnhilde sends him into the world to do heroic deeds. As a pledge of his love, Siegfried gives her the ring that he took from the dragon Fafner, and she offers her horse, Grane, in return. Siegfried sets off on his travels. Act I In the hall of the Gibichungs on the banks of the Rhine, Hagen advises his half- siblings, Gunther and Gutrune, to strengthen their rule through marriage. He suggests Brünnhilde as Gunther’s bride and Siegfried as Gutrune’s husband. Since only the strongest hero can pass through the fire on Brünnhilde’s rock, Hagen proposes a plan: A potion will make Siegfried forget Brünnhilde and fall in love with Gutrune. To win her, he will claim Brünnhilde for Gunther. When Siegfried’s horn is heard from the river, Hagen calls him ashore. Gutrune offers him the potion. Siegfried drinks and immediately confesses his love for her.Ð When Gunther describes the perils of winning his chosen bride, Siegfried offers to use the Tarnhelm to transform himself into Gunther. -

The Ring Sample Lesson Plan: Wagner and Women **Please Note That This Lesson Works Best Post-Show

The Ring Sample Lesson Plan: Wagner and Women **Please note that this lesson works best post-show Educator should choose which female character to focus on based on the opera(s) the group has attended. See below for the list of female characters in each opera: Das Rheingold: Fricka, Erda, Freia Die Walküre: Brunhilde, Sieglinde, Fricka Siegfried: Brunhilde, Erda Götterdämmerung: Brunhilde, Gutrune GRADE LEVELS 6-12 TIMING 1-2 periods PRIOR KNOWLEDGE Educator should be somewhat familiar with the female characters of the Ring AIM OF LESSON Compare and contrast the actual women in Wagner’s life to the female characters he created in the Ring OBJECTIVES To explore the female characters in the Ring by studying Wagner’s relationship with the women in his life CURRICULAR Language Arts CONNECTIONS History and Social Studies MATERIALS Computer and internet access. Some preliminary resources listed below: Brunhilde in the “Ring”: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brynhildr#Wagner's_%22Ring%22_cycle) First wife Minna Planer: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minna_Planer) o Themes: turbulence, infidelity, frustration Mistress Mathilde Wesendonck: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mathilde_Wesendonck) o Themes: infatuation, deep romantic attachment that’s doomed, unrequited love Second wife Cosima Wagner: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosima_Wagner) o Themes: devotion to Wagner and his works; Wagner’s muse Wagner’s relationship with his mother: (https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/richard-wagner-392.php) o Theme: mistrust NATIONAL CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.7.9 STANDARDS/ Compare and contrast a fictional portrayal of a time, place, or character and a STATE STANDARDS historical account of the same period as a means of understanding how authors of fiction use or alter history. -

05-09-2019 Siegfried Eve.Indd

Synopsis Act I Mythical times. In his cave in the forest, the dwarf Mime forges a sword for his foster son Siegfried. He hates Siegfried but hopes that the youth will kill the dragon Fafner, who guards the Nibelungs’ treasure, so that Mime can take the all-powerful ring from him. Siegfried arrives and smashes the new sword, raging at Mime’s incompetence. Having realized that he can’t be the dwarf’s son, as there is no physical resemblance between them, he demands to know who his parents were. For the first time, Mime tells Siegfried how he found his mother, Sieglinde, in the woods, who died giving birth to him. When he shows Siegfried the fragments of his father’s sword, Nothung, Siegfried orders Mime to repair it for him and storms out. As Mime sinks down in despair, a stranger enters. It is Wotan, lord of the gods, in human disguise as the Wanderer. He challenges the fearful Mime to a riddle competition, in which the loser forfeits his head. The Wanderer easily answers Mime’s three questions about the Nibelungs, the giants, and the gods. Mime, in turn, knows the answers to the traveler’s first two questions but gives up in terror when asked who will repair the sword Nothung. The Wanderer admonishes Mime for inquiring about faraway matters when he knows nothing about what closely concerns him. Then he departs, leaving the dwarf’s head to “him who knows no fear” and who will re-forge the magic blade. When Siegfried returns demanding his father’s sword, Mime tells him that he can’t repair it. -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

The Orchestra in History

Jeremy Montagu The Orchestra in History The Orchestra in History A Lecture Series given in the late 1980s Jeremy Montagu © Jeremy Montagu 2017 Contents 1 The beginnings 1 2 The High Baroque 17 3 The Brandenburg Concertos 35 4 The Great Change 49 5 The Classical Period — Mozart & Haydn 69 6 Beethoven and Schubert 87 7 Berlioz and Wagner 105 8 Modern Times — The Age Of The Dinosaurs 125 Bibliography 147 v 1 The beginnings It is difficult to say when the history of the orchestra begins, be- cause of the question: where does the orchestra start? And even, what is an orchestra? Does the Morley Consort Lessons count as an orchestra? What about Gabrieli with a couple of brass choirs, or even four brass choirs, belting it out at each other across the nave of San Marco? Or the vast resources of the Striggio etc Royal Wedding and the Florentine Intermedii, which seem to have included the original four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie, or at least a group of musicians popping out of the pastry. I’m not sure that any of these count as orchestras. The Morley Consort Lessons are a chamber group playing at home; Gabrieli’s lot wasn’t really an orchestra; The Royal Wed- dings and so forth were a lot of small groups, of the usual renais- sance sorts, playing in turn. Where I am inclined to start is with the first major opera, Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. Even that tends to be the usual renaissance groups taking turn about, but they are all there in a coherent dra- matic structure, and they certainly add up to an orchestra. -

Johannes Brahms and Hans Von Buelow

The Library Chronicle Volume 1 Number 3 University of Pennsylvania Library Article 5 Chronicle October 1933 Johannes Brahms and Hans Von Buelow Otto E. Albrecht Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/librarychronicle Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Albrecht, O. E. (1933). Johannes Brahms and Hans Von Buelow. University of Pennsylvania Library Chronicle: Vol. 1: No. 3. 39-46. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/librarychronicle/vol1/iss3/5 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/librarychronicle/vol1/iss3/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. not later than 1487. Incidentally it may be mentioned that the Gesamtkatalog fully records a "Seitengetreuer Nach- druck" (mentioned by Proctor) as of [Strassburg, Georg Husner, um 1493/94]. The two editions (of which Dr. Ros- enbach's gift is the original) have the same number of leaves but the register of signatures is different. And now in 1933 comes the Check list of fifteenth century books in the New- berry Library, compiled by Pierce Butler, capping the struc- ture with the date given as [1488] and the printer Johann Priiss, OTHER RECENT GIFTS Through the generosity of Mr. Joseph G. Lester the Library has received a copy of Lazv Triumphant, by Violet Oakley. The first volume of this beautifully published work contains a record of the ceremonies at the unveiling of Miss Oakley's mural paintings, "The Opening of the Book of the Law," in the Supreme Court room at Harrisburg, and the artist's journal during the Disarmament Conference at Gen- eva. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

ARSC Journal, Vol.21, No

Sound Recording Reviews Wagner: Parsifal (excerpts). Berlin State Opera Chorus and Orchestra (a) Bayreuth Festival Chorus and Orchestra (b), cond. Karl Muck. Opal 837/8 (LP; mono). Prelude (a: December 11, 1927); Act 1-Transformation & Grail Scenes (b: July/ August, 1927); Act 2-Flower Maidens' Scene (b: July/August, 1927); Act 3 (a: with G. Pistor, C. Bronsgeest, L. Hofmann; slightly abridged; October 10-11and13-14, 1928). Karl Muck conducted Parsifal at every Bayreuth Festival from 1901 to 1930. His immediate predecessor was Franz Fischer, the Munich conductor who had alternated with Hermann Levi during the premiere season of 1882 under Wagner's own supervi sion. And Muck's retirement, soon after Cosima and Siegfried Wagner died, brought another changing of the guard; Wilhelm Furtwangler came to the Green Hill for the next festival, at which Parsifal was controversially assigned to Arturo Toscanini. It is difficult if not impossible to tell how far Muck's interpretation of Parsifal reflected traditions originating with Wagner himself. Muck's act-by-act timings from 1901 mostly fall within the range defined in 1882 by Levi and Fischer, but Act 1 was decidedly slower-1:56, compared with Levi's 1:47 and Fischer's 1:50. Muck's timing is closer to that of Felix Mottl, who had been a musical assistant in 1882, and of Hans Knappertsbusch in his first and slowest Bayreuth Parsifal. But in later summers Muck speeded up to the more "normal" timings of 1:50 and 1:47, and the extensive recordings he made in 1927-8, now republished by Opal, show that he could be not only "sehr langsam" but also "bewegt," according to the score's requirements. -

Constructing the Archive: an Annotated Catalogue of the Deon Van Der Walt

(De)constructing the archive: An annotated catalogue of the Deon van der Walt Collection in the NMMU Library Frederick Jacobus Buys January 2014 Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Music (Performing Arts) at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Supervisor: Prof Zelda Potgieter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION i ABSTRACT ii OPSOMMING iii KEY WORDS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION TO THIS STUDY 1 1. Aim of the research 1 2. Context & Rationale 2 3. Outlay of Chapters 4 CHAPTER 2 - (DE)CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHIVE: A BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CHAPTER 3 - DEON VAN DER WALT: A LIFE CUT SHORT 9 CHAPTER 4 - THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION: AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE 12 CHAPTER 5 - CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 1. The current state of the Deon van der Walt Collection 18 2. Suggestions and recommendations for the future of the Deon van der Walt Collection 21 SOURCES 24 APPENDIX A PERFORMANCE AND RECORDING LIST 29 APPEDIX B ANNOTED CATALOGUE OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION 41 APPENDIX C NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSTITY LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICES (NMMU LIS) - CIRCULATION OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT (DVW) COLLECTION (DONATION) 280 APPENDIX D PAPER DELIVERED BY ZELDA POTGIETER AT THE OFFICIAL OPENING OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION, SOUTH CAMPUS LIBRARY, NMMU, ON 20 SEPTEMBER 2007 282 i DECLARATION I, Frederick Jacobus Buys (student no. 211267325), hereby declare that this treatise, in partial fulfilment for the degree M.Mus (Performing Arts), is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment or completion of any postgraduate qualification to another University or for another qualification. -

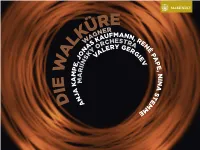

WAGNER / Рихард Вагнер DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (Conclusion) 1 Xii

lk a Waü GN r W , joNas k e e pe kY au r m iNs or f e ri C m i a a Val H k er e a m Y s N a t D j N G r N e , a r a r e G N i e é V p a p e , N i N a s t e e m m 2 Die Walküre Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (conclusion) 1 xii. Schwer wiegt mir der Waffen Wucht / My load of armour weighs heavy on me p18 2’28” DiE WAlkÜRE 2 xiii. Dritte Szene: Raste nun hier, gönne dir Ruh’! / Scene Three: Do stop here, and take a rest p18 8’56” (ThE VAlkyRiE / ВалькиРия) 3 xiv. Wo bist du, Siegmund? / Where are you, Siegmund? p19 3’49” 4 xv. Vierte Szene: Siegmund! Sieh auf mich! / Scene Four: Siegmund, look at me p19 10’55” Siegmund / Зигмунд...................................................................................................................................Jonas KAUFMANN / Йонас Кауфман 5 xvi. Du sahst der Walküre sehrenden Blick / you have seen the Valkyrie’s searing glance p20 4’27” hunding / Хундинг................................. ..............................................................................................Mikhail PETRENKO / михаил ПетренКо 6 xvii. So jung un schön erschimmerst du mir / So young and fair and dazzling you look p20 4’58” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René Pape / рене ПаПе 7 xviii. Funfte Szene: Zauberfest bezähmt ein Schlaf / Scene Five: Deep as a spell sleep subdues p21 3’01” Sieglinde / Зиглинда........................................................................................................................................................Anja