Vine Hill Clarkia Draft Recovery Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qty Size Name 6 1G Abies Bracteata 10 1G Abutilon Palmeri 1 1G Acaena Pinnatifida Var

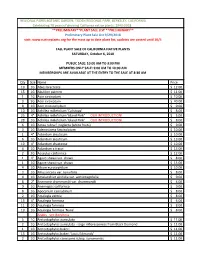

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 76 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2016 **FINAL**PLANT SALE LIST **FINAL** (9/30/2016 @ 6:00 PM) visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2016 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name 6 1G Abies bracteata 10 1G Abutilon palmeri 1 1G Acaena pinnatifida var. californica 18 1G Achillea millefolium 10 4" Achillea millefolium - Black Butte 28 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 8 4" Achillea millefolium 'Rosy Red' - donated by Annie's Annuals 2 4" Achillea millefolium 'Sonoma Coast' 7 4" Acmispon (Lotus) argophyllus var. argenteus 9 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) 25 4" Adiantum x tracyi (A. jordanii x A. aleuticum) 5 1G Aesculus californica 1 2G Agave shawii var. shawii 2 1G Agoseris grandiflora 8 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 2 2G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 5 4" Ambrosia pumila 5 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia 9 1G Anemopsis californica 5 1G Angelica hendersonii 3 1G Angelica tomentosa 1 1G Apocynum androsaemifolium x Apocynum cannabinum 7 1G Apocynum cannabinum 5 1G Aquilegia formosa 2 4" Aquilegia formosa 4 4" Arbutus menziesii 2 1G Arctostaphylos andersonii 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata 3 1G Arctostaphylos 'Austin Griffith' 11 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 5 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Clarkia Tenella Is Tetraploid, Having N 34 (Hiorth, 1941; Raven and Lewis, 1959) and 2Fl32 (Moore and Lewis, I965b)

VARIATION AND EVOLUTION IN SOUTH AMERICAN CLARKIA D. M. MOORE and HARLAN LEWiS Botany Department, University of Leicester and Botany Department, University of California, Los Angeles Received5.V.65 1.INTRODUCTION THEgenus Clarkia (Onagracee), currently considered to contain 36 species, is restricted to the western parts of North and South America (fig. i). The 35 North American species are distributed from Baja California to British Columbia (300N.to 48° N.), most of them occurring in California. The South American populations, which have a smaller though still considerable latitudinal spread (290 30' S. to 42030'S.), comprise a single variable species, Clarkia tenella (Cay.) H. and M. Lewis (Lewis and Lewis, within which four sub.. species have been recognised (Moore and Lewis, i 965b). Clarkia tenella is tetraploid, having n 34 (Hiorth, 1941; Raven and Lewis, 1959) and 2fl32 (Moore and Lewis, i965b). It is placed in section Godetia, together with seven North American species, and shows its closest affinities with the only tetraploid among these, C. davyi (Jeps.) H. and M. Lewis. A study of artificial hybrids between C. tenella and C. davji, together with pakeo-ecological evidence, led Raven and Lewis (i) to hypothesise that the two species were derived from a common tetraploid ancestor which had traversed the tropics by long-distance dispersal during or since the Late-Tertiary and given rise to the populations now comprising C. tenella. Detailed study of the variation within Clarkia tenella was made possible by a field trip to Chile and Argentina during 1960-61 and by subsequent experimental work at Leicester and Los Angeles. -

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

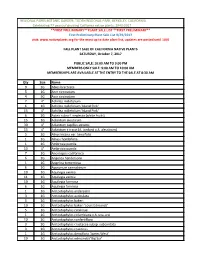

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Publications of Peter H. Raven

Peter H. Raven LIST OF PUBLICATIONS 1950 1. 1950 Base Camp botany. Pp. 1-19 in Base Camp 1950, (mimeographed Sierra Club report of trip). [Upper basin of Middle Fork of Bishop Creek, Inyo Co., CA]. 1951 2. The plant list interpreted for the botanical low-brow. Pp. 54-56 in Base Camp 1951, (mimeographed Sierra Club report of trip). 3. Natural science. An integral part of Base Camp. Pp. 51-52 in Base Camp 1951, (mimeographed Sierra Club report of trip). 4. Ediza entomology. Pp. 52-54 in Base Camp 1951, (mimeographed Sierra Club report of trip). 5. 1951 Base Camp botany. Pp. 51-56 in Base Camp 1951, (mimeographed Sierra Club report of trip). [Devils Postpile-Minaret Region, Madera and Mono Counties, CA]. 1952 6. Parsley for Marin County. Leafl. West. Bot. 6: 204. 7. Plant notes from San Francisco, California. Leafl. West. Bot. 6: 208-211. 8. 1952 Base Camp bird list. Pp. 46-48 in Base Camp 1952, (mimeographed Sierra Club report of trip). 9. Charybdis. Pp. 163-165 in Base Camp 1952, (mimeographed Sierra Club report of trip). 10. 1952 Base Camp botany. Pp. 1-30 in Base Camp 1952, (mimeographed Sierra Club report of trip). [Evolution Country - Blaney Meadows - Florence Lake, Fresno, CA]. 11. Natural science report. Pp. 38-39 in Base Camp 1952, (mimeographed Sierra Club report of trip). 1953 12. 1953 Base Camp botany. Pp. 1-26 in Base Camp 1953, (mimeographed Sierra Club report of trip). [Mono Recesses, Fresno Co., CA]. 13. Ecology of the Mono Recesses. Pp. 109-116 in Base Camp 1953, (illustrated by M. -

Verdura® Native Planting

Abronia maritime Abronia maritima is a species of sand verbena known by the common name red (Coastal) sand verbena. This is a beach-adapted perennial plant native to the coastlines of southern California, including the Channel Islands, and northern Baja California. Abronia villosa Abronia villosa is a species of sand-verbena known by the common name desert (Inland) sand-verbena. It is native to the deserts of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico and the southern California and Baja coast. Adenostoma Adenostoma fasciculatum (chamise or greasewood) is a flowering plant native to fasciculatum California and northern Baja California. This shrub is one of the most widespread (Coastal/Inland) plants of the chaparral biome. Adenostoma fasciculatum is an evergreen shrub growing to 4m tall, with dry-looking stick-like branches. The leaves are small, 4– 10 mm long and 1mm broad with a pointed apex, and sprout in clusters from the branches. Arctostaphylos Arctostaphylos uva-ursi is a plant species of the genus Arctostaphylos (manzanita). uva-ursi Its common names include kinnikinnick and pinemat manzanita, and it is one of (Coastal/Inland) several related species referred to as bearberry. Arctostaphylos Arctostaphylos edmundsii, with the common name Little Sur manzanita, is a edmundsii species of manzanita. This shrub is endemic to California where it grows on the (Coastal/Inland) coastal bluffs of Monterey County. Arctostaphylos Arctostaphylos hookeri is a species of manzanita known by the common name hookeri Hooker's manzanita. Arctostaphylos hookeri is a low shrub which is variable in (Coastal/Inland) appearance and has several subspecies. The Arctostaphylos hookeri shrub is endemic to California where its native range extends from the coastal San Francisco Bay Area to the Central Coast. -

Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies Bracteata 5 1G Acer Circinatum 4 5G Acer

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 77 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2017 **FIRST PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **FIRST PRELIMINARY** First Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2017 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/6 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 7, 2017 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies bracteata 5 1G Acer circinatum 4 5G Acer circinatum 7 4" Achillea millefolium 6 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 15 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) 15 1G Adiantum aleuticum 30 4" Adiantum capillus-veneris 15 4" Adiantum x tracyi (A. jordanii x A. aleuticum) 5 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 1 1G Alnus rhombifolia 1 1G Ambrosia pumila 13 4" Ambrosia pumila 7 1G Anemopsis californica 6 1G Angelica hendersonii 1 1G Angelica tomentosa 6 1G Apocynum cannabinum 10 1G Aquilegia eximia 11 1G Aquilegia eximia 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 6 1G Aquilegia formosa 1 1G Arctostaphylos andersonii 3 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata 5 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 10 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' 5 1G Arctostaphylos catalinae 1 1G Arctostaphylos columbiana x A. uva-ursi 10 1G Arctostaphylos confertiflora 3 1G Arctostaphylos crustacea subsp. subcordata 3 1G Arctostaphylos cruzensis 1 1G Arctostaphylos densiflora 'James West' 10 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 2 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 22 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii var. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abella, S. R. 2010. Disturbance and plant succession in the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts of the American Southwest. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 7:1248—1284. Abella, S. R., D. J. Craig, L. P. Chiquoine, K. A. Prengaman, S. M. Schmid, and T. M. Embrey. 2011. Relationships of native desert plants with red brome (Bromus rubens): Toward identifying invasion-reducing species. Invasive Plant Science and Management 4:115—124. Abella, S. R., N. A. Fisichelli, S. M. Schmid, T. M. Embrey, D. L. Hughson, and J. Cipra. 2015. Status and management of non-native plant invasion in three of the largest national parks in the United States. Nature Conservation 10:71—94. Available: https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.10.4407 Abella, S. R., A. A. Suazo, C. M. Norman, and A. C. Newton. 2013. Treatment alternatives and timing affect seeds of African mustard (Brassica tournefortii), an invasive forb in American Southwest arid lands. Invasive Plant Science and Management 6:559—567. Available: https://doi.org/10.1614/IPSM-D-13-00022.1 Abrahamson, I. 2014. Arctostaphylos manzanita. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Fire Effects Information System (Online). plants/shrub/arcman/all.html Ackerman, T. L. 1979. Germination and survival of perennial plant species in the Mojave Desert. The Southwestern Naturalist 24:399—408. Adams, A. W. 1975. A brief history of juniper and shrub populations in southern Oregon. Report No. 6. Oregon State Wildlife Commission, Corvallis, OR. Adams, L. 1962. Planting depths for seeds of three species of Ceanothus. -

Adenostoma Fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos Canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos Virgata (Marin Manzanita) Alison S

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 5-20-2016 Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species--Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita) Alison S. Pollack University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Pollack, Alison S., "Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species-- Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita)" (2016). Master's Projects and Capstones. 352. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/352 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 This Master's Project Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species--Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita) by Alison S. Pollack is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Science in Environmental Management at the University of San Francisco Submitted: Received: ................................…………. -

Classification of the Vegetation Alliances and Associations of Sonoma County, California

Classification of the Vegetation Alliances and Associations of Sonoma County, California Volume 1 of 2 – Introduction, Methods, and Results Prepared by: California Department of Fish and Wildlife Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program California Native Plant Society Vegetation Program For: The Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District The Sonoma County Water Agency Authors: Anne Klein, Todd Keeler-Wolf, and Julie Evens December 2015 ABSTRACT This report describes 118 alliances and 212 associations that are found in Sonoma County, California, comprising the most comprehensive local vegetation classification to date. The vegetation types were defined using a standardized classification approach consistent with the Survey of California Vegetation (SCV) and the United States National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) system. This floristic classification is the basis for an integrated, countywide vegetation map that the Sonoma County Vegetation Mapping and Lidar Program expects to complete in 2017. Ecologists with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the California Native Plant Society analyzed species data from 1149 field surveys collected in Sonoma County between 2001 and 2014. The data include 851 surveys collected in 2013 and 2014 through funding provided specifically for this classification effort. An additional 283 surveys that were conducted in adjacent counties are included in the analysis to provide a broader, regional understanding. A total of 34 tree-overstory, 28 shrubland, and 56 herbaceous alliances are described, with 69 tree-overstory, 51 shrubland, and 92 herbaceous associations. This report is divided into two volumes. Volume 1 (this volume) is composed of the project introduction, methods, and results. It includes a floristic key to all vegetation types, a table showing the full local classification nested within the USNVC hierarchy, and a crosswalk showing the relationship between this and other classification systems. -

Arctostaphylos Photos Susan Mcdougall Arctostaphylos Andersonii

Arctostaphylos photos Susan McDougall Arctostaphylos andersonii Santa Cruz Manzanita Arctostaphylos auriculata Mount Diablo Manzanita Arctostaphylos bakeri ssp. bakeri Baker's Manzanita Arctostaphylos bakeri ssp. sublaevis The Cedars Manzanita Arctostaphylos canescens ssp. canescens Hoary Manzanita Arctostaphylos canescens ssp. sonomensis Sonoma Canescent Manzanita Arctostaphylos catalinae Catalina Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos columbiana Columbia Manzanita Arctostaphylos confertiflora Santa Rosa Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. crinita Crinite Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. crustacea Brittleleaf Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. rosei Rose's Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. subcordata Santa Cruz Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos cruzensis Arroyo De La Cruz Manzanita Arctostaphylos densiflora Vine Hill Manzanita Arctostaphylos edmundsii Little Sur Manzanita Arctostaphylos franciscana Franciscan Manzanita Arctostaphylos gabilanensis Gabilan Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. adamsii Adam's Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. crassifolia Del Mar Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. cushingiana Cushing's Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. glandulosa Eastwood Manzanita Arctostaphylos glauca Big berry Manzanita Arctostaphylos hookeri ssp. hearstiorum Hearst's Manzanita Arctostaphylos hookeri ssp. hookeri Hooker's Manzanita Arctostaphylos hooveri Hoover’s Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. howellii Howell's Manzanita Arctostaphylos insularis Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos luciana -

Arctostaphylos: the Winter Wonder by Lili Singer, Special Projects Coordinator

WINTER 2010 the Poppy Print Quarterly Newsletter of the Theodore Payne Foundation Arctostaphylos: The Winter Wonder by Lili Singer, Special Projects Coordinator f all the native plants in California, few are as glass or shaggy and ever-peeling. (Gardeners, take note: smooth- beloved or as essential as Arctostaphylos, also known bark species slough off old “skins” every year in late spring or as manzanita. This wild Californian is admired by summer, at the end of the growing season.) gardeners for its twisted boughs, elegant bark, dainty Arctostaphylos species fall into two major groups: plants that flowers and handsome foliage. Deep Arctostaphylos roots form a basal burl and stump-sprout after a fire, and those that do prevent erosion and stabilize slopes. Nectar-rich insect-laden not form a burl and die in the wake of fire. manzanita blossoms—borne late fall into spring—are a primary food source for resident hummingbirds and their fast-growing Small, urn-shaped honey-scented blossoms are borne in branch- young. Various wildlife feast on the tasty fruit. end clusters. Bees and hummers thrive on their contents. The Wintershiny, round red fruit or manzanita—Spanish for “little apple”— The genus Arctostaphylos belongs to the Ericaceae (heath O are savored by coyotes, foxes, bears, other mammals and quail. family) and is diverse, with species from chaparral, coastal and (The botanical name Arctostaphylos is derived from Greek words mountain environments. for bear and grape.) Humans use manzanita fruit for beverages, Though all “arctos” are evergreen with thick leathery foliage, jellies and ground meal, and both fruit and foliage have plant habits range from large and upright to low and spreading. -

Bob Allen's OCCNPS Presentation About Plant Families.Pages

Stigma How to identify flowering plants Style Pistil Bob Allen, California Native Plant Society, OC chapter, occnps.org Ovary Must-knows • Flower, fruit, & seed • Leaf parts, shapes, & divisions Petal (Corolla) Anther Stamen Filament Sepal (Calyx) Nectary Receptacle Stalk Major local groups ©Bob Allen 2017 Apr 18 Page !1 of !6 A Botanist’s Dozen Local Families Legend: * = non-native; (*) = some native species, some non-native species; ☠ = poisonous Eudicots • Leaf venation branched; veins net-like • Leaf bases not sheathed (sheathed only in Apiaceae) • Cotyledons 2 per seed • Floral parts in four’s or five’s Pollen apertures 3 or more per pollen grain Petal tips often • curled inward • Central taproot persists 2 styles atop a flat disk Apiaceae - Carrot & Parsley Family • Herbaceous annuals & perennials, geophytes, woody perennials, & creepers 5 stamens • Stout taproot in most • Leaf bases sheathed • Leaves alternate (rarely opposite), dissected to compound Style “horns” • Flowers in umbels, often then in a secondary umbel • Sepals, petals, stamens 5 • Ovary inferior, with 2 chambers; styles 2; fruit a dry schizocarp Often • CA: Apiastrum, Yabea, Apium*, Berula, Bowlesia, Cicuta, Conium*☠ , Daucus(*), vertically Eryngium, Foeniculum, Torilis*, Perideridia, Osmorhiza, Lomatium, Sanicula, Tauschia ribbed • Cult: Apium, Carum, Daucus, Petroselinum Asteraceae - Sunflower Family • Inflorescence a head: flowers subtended by an involucre of bracts (phyllaries) • Calyx modified into a pappus • Corolla of 5 fused petals, radial or bilateral, sometimes both kinds in same head • Radial (disk) corollas rotate to salverform • Bilateral (ligulate) corollas strap-shaped • Stamens 5, filaments fused to corolla, anthers fused into a tube surrounding the style • Ovary inferior, style 1, with 2 style branches • Fruit a cypsela (but sometimes called an achene) • The largest family of flowering plants in CA (ca.