Completing the Collective Security Mechanism of the Charter: Establishing an International Peace Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EE~1F#.~~§:;~~~~L~~:K~:F~~M~:~~~;~~R1'

.-~- - .. , ., 1 i" Ia 1.92' lax LeHBt.bal Aat.ed ,bat. ... 1IU ~al Cou.o.M1 for t.be ~:--",-::.:-:' \ . ~:tu.1u -.noaA 1D4R8t.J's.a1 ~~NtlOD, ~ UzdGA ~, .... tork Cit.1. '. h a pro.peot.u. publl.be4 ~ wu.' ~r,porat.lon tor Use paJ",po.. Dr ra1dQi ..0:;" ,. , "\ Mpit.al, 1t. 1••t.at.ed t.bat. t.be pl.&n tor ergan1.ut.1cm or a a1.11ion dollu - '. .._,. '\ eoropoJ"l,t.1on a. ~aor1bed. in 'be proa~t.Il' 1IU an out.iPowt.b or t.be ridt. or ~,", -'.:' :.... ""\ Slclney l:llla&n, rr.aident of t.he AuJ.&...t.e~ Clot.tU.n& aorkv. or AMrlc-&, . ,k iIled.• in UM n-er or 1921• .:.. - ..;,..' '.' "\ !he et.at.ed purpoH .r tbe eorpont.iOa .... -"" &1d and udat. 1n ~co·:\ EE~1f#.~~§:;~~~~L~~:k~:f~~m~:~~~;~~r1'. ~_. -:',-"-<- .1 oODeN.lena 1M:IUld be ".t.ed in repnaeat.at.ina or the Bupreae Council or !!t.t1o:u:.l l.eonoorl.clS or t.he Sc-v1et Go,.er~ent and or the RU!8i~ .~erice..n l~dl.'.~t-!"i=.l Corporation. In a pasphlet blUed by t.hie oorporat10n t.he" appeared t.he na.mesof • ;os \ Mr. and ~.. M&x Lowent.hal as wblc1"1ber. '0 MIa.ian AMrican ~.t.rial - ~':~~'~ .- _" .\CorporaUon .t.ook. 62-25733-ZW page 2 ~ .::-~.~-":..-:-.', "'", -) .','-~ i 'In rebruaP7 1942 the let.t..rhead or 'be Int.ernatiooal. Juridica.l '-:"'. ,,-.~~}..Sloc1at.lon oarried t.be ~e ,or Max l.o1tent.hal u be1n£ a aMber or t.he lational :. ''.. ~ttee NpN.ent.1n& t.he DUtJ"1ct. -

Temple Library Database 2017-05-17

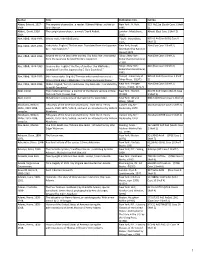

Temple Sholom Library 6/9/2017 BOOK PUB CALL TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY KEYWORDS FORMAT DATE NUMBER Children's Books : Literature : 10 Traditional Jewish Children's Stories Goldreich, Gloria Hardcover 1996 Children's stories, Hebrew, Legends, Jewish J 185.6 Go Classics by Age : General Feldman, 100+ Jewish Art Projects for Children Paperback 1996 Religion Biblical Studies Bible. O.T. Pentateuch Textbooks Margaret A. Language selfstudy & 1001 Yiddish Proverbs Kogos, Fred Paperback 1990 phrasebooks 101 Classic Jewish Jokes : Jewish Humor from Groucho Marx to Jerry Menchin, Robert Paperback 1997 Entertainment : Humor : General Jewish wit and humor 550.7 Seinfeld World War, 19141918 Peace, World War, 19141918 1918: War and Peace Dallas, Gregor Hardcover 2001 20th Century World History Armistices Kipfer, Barbara English language Style Handbooks, manuals,, etc, 21ST Century Style Manual Paperback 1993 English Composition Ann English language Usage Dictionaries 26 Big Things Small Hands Do Paratore, Coleen Paperback 1905 Tikkun olam J Pa 300 ways to ask the four questions : from Zulu to Abkhaz : an extraordinary survey of the world's languages through the prism of the Spiegel, Murray Hardcover 1905 Passover Mah nishtannah Translations 244.4 Sp Haggadah 5,600 Jokes for All Occasions Meiers, Mildred Hardcover 1905 Jewish Humor Jewish Humor 550.7 Me 50 Ways to be Jewish: Or, Simon & Garfunkel, Jesus loves you less Forman, David J. Hardcover 2001 Jewish living Jewish way of life, Judaism 20th century 246 Fo than you will know 700 sundays Crystal, Billy Hardcover 1905 Crystal, Billy Crystal, Billy, Comedians United States Biography B Cr FinkWhitman, 94 Maidens Paperback 1905 Fiction F Fi Rhonda A Backpack, A Bear, and Eight Crates of Vodka Golinkin, Lev Paperback 1905 Biographies & Memoirs B Go Jews Folklore, Folklore Europe, Eastern, Yiddish Folk A Big Quiet House Forest, Heather Hardcover 1996 Folklore J 185.6 Fo Tales Jews New York (State) New York Social, life and customs, Immigrants New York (State) New York , A Bintel brief. -

University of Cincinnati

! "# $ % & % ' % !" #$ !% !' &$ &""! '() ' #$ *+ ' "# ' '% $$(' ,) * !$- .*./- 0 #!1- 2 *,*- Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2010 by Wolfgang Lueckel B.A. (equivalent) in German Literature, Universität Mainz, 2003 M.A. in German Studies, University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: Sara Friedrichsmeyer, Ph.D. Committee Members: Todd Herzog, Ph.D. (second reader) Katharina Gerstenberger, Ph.D. Richard E. Schade, Ph.D. ii Abstract In my dissertation “Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture,” I investigate the portrayal of the nuclear age and its most dreaded fantasy, the nuclear apocalypse, in German fictionalizations and cultural writings. My selection contains texts of disparate natures and provenance: about fifty plays, novels, audio plays, treatises, narratives, films from 1946 to 2009. I regard these texts as a genre of their own and attempt a description of the various elements that tie them together. The fascination with the end of the world that high and popular culture have developed after 9/11 partially originated from the tradition of nuclear fiction since 1945. The Cold War has produced strong and lasting apocalyptic images in German culture that reject the traditional biblical apocalypse and that draw up a new worldview. In particular, German nuclear fiction sees the atomic apocalypse as another step towards the technical facilitation of genocide, preceded by the Jewish Holocaust with its gas chambers and ovens. -

ED 194 419 EDRS PRICE Jessup, John E., Jr.: Coakley, Robert W. A

r r DOCUMENT RESUME ED 194 419 SO 012 941 - AUTHOR Jessup, John E., Jr.: Coakley, Robert W. TITLE A Guide to the Study and use of Military History. INSTITUTION Army Center of Military History, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 79 NOTE 497p.: Photographs on pages 331-336 were removed by ERIC due to poor reproducibility. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 ($6.50). EDRS PRICE MF02/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *History: military Personnel: *Military Science: *Military Training: Study Guides ABSTRACT This study guide On military history is intended for use with the young officer just entering upon a military career. There are four major sections to the guide. Part one discusses the scope and value of military history, presents a perspective on military history; and examines essentials of a study program. The study of military history has both an educational and a utilitarian value. It allows soldiers to look upon war as a whole and relate its activities to the periods of peace from which it rises and to which it returns. Military history also helps in developing a professional frame of mind and, in the leadership arena, it shows the great importance of character and integrity. In talking about a study program, the guide says that reading biographies of leading soldiers or statesmen is a good way to begin the study of military history. The best way to keep a study program current is to consult some of the many scholarly historical periodicals such as the "American Historical Review" or the "Journal of Modern History." Part two, which comprises almost half the guide, contains a bibliographical essay on military history, including great military historians and philosophers, world military history, and U.S. -

Norman Cousins Papers, 1924-1991, Bulk 1944-1990

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft558004w3 No online items Finding Aid for the Norman Cousins papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Processed by Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Norman 1385 1 Cousins papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Finding Aid for the Norman Cousins Papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Collection number: 1385 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Contact Information Manuscripts Division UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Telephone: 310/825-4988 (10:00 a.m. - 4:45 p.m., Pacific Time) Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ Processed by: Manuscripts Division staff Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Text converted and initial container list EAD tagging in part by: Apex Data Services © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Norman Cousins papers, Date (inclusive): 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Collection number: 1385 Creator: Cousins, Norman. Extent: 1816 boxes (908 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. -

Surpass Shelf List

Beth Sholom B'Nai Israel Shelf List Barcode Call Author Title Cost 1001502 Daily prayer book = : Ha-Siddur $0.00 ha-shalem / translated and annotated with an introduction by Philip Birnbaum. 1000691 Documents on the Holocaust : $0.00 selected sources on the destruction of the Jews of Germany and Austria, Poland, and the Soviet Union / edited by Yitzhak Arad, Yisrael Gutman, Abraham Margaliot. 1001830 Explaining death to children / $0.00 Edited by Earl A. Grollman. 1003811 In the tradition : an anthology $0.00 of young Black writers / edited by Kevin Powell and Ras Baraka. 1003812 In the tradition : an anthology $0.00 of young Black writers / edited by Kevin Powell and Ras Baraka. 1002040 Jewish art and civilization / $0.00 editor-in-chief: Geoffrey Wigoder. 1001839 The Jews / edited by Louis $0.00 Finkelstein. 56 The last butterfly $0.00 [videorecording] / Boudjemaa Dahmane et Jacques Methe presentent ; Cinema et Communication and Film Studio Barrandov with Filmexport Czechoslovakia in association with HTV International Ltd. ; [The Blum Group and Action Media Group 41 The magician of Lublin $0.00 [videorecording] / Cannon Video. 1001486 My people's Passover Haggadah : $0.00 traditional texts, modern commentaries / edited by Lawrence A. Hoffman and David Arnow. 1001487 My people's Passover Haggadah : $0.00 traditional texts, modern commentaries / edited by Lawrence A. Hoffman and David Arnow. 1003430 The Prophets (Nevi'im) : a new $0.00 trans. of the Holy Scriptures according to the Masoretic text. Second section. 1001506 Seder K'riat Hatorah (the Torah $0.00 8/9/2021 Surpass Page 1 Beth Sholom B'Nai Israel Shelf List Barcode Call Author Title Cost service) / edited by Lawrence A. -

HOUSE FEBRU~RY 26 the PRESIDING OFFICER

1768 CONGRESSIONAL _RECORD-HOUSE FEBRU~RY 26 The PRESIDING OFFICER. With· Services Committee, which seeks to · is widely held in Oklahoma that the land out objection, they will be passed over. transfer · the Remount Service from the. is potentially valuable as a possible site HOME LOAN BANK BOARD Army to the Department of Agriculture, for the 'discovery of . oil and the drilling was favorably reported by the Armed of oil wells, and I think the Federal Gov The legislative clerk read the nomina· Services Committee by unanimous vote, ernment has a great interest in that . tion of J. Alston Adams, of New Jersey, and is based upon an agreement which potentiality. ' · to be a member of the Home Loan Bank already has been worked out by the Army I desire further to point out that the Board. and the Department of Agriculture. horse industry of the country has come The PRESIDING OFFICER. With· In view of the hearings we have had to rely on the Remount Service dur out objection, the nomination is con· in the Armed Services Committee and ing the course of many years. 1;here firmed. in view of the extensive negotiations are millions of dollars of Federal money The legislative clerk read the nomina~ which have taken place between the invested in it. Contrary to the impli· tion of William K. Divers, of Ohio, to be Army and the Department of Agricul· cations of the comments · of the Senator a member of the Home Loan Bank Board. ture, certainly I do not think any good from Oklahoma, there is a great demand The PRESIDING OFFICER. -

Viewer of the First English by Engels from Marx’S Posthumous Papers

1 FOR THE COLLECTION OF A LIFETIME The process of creating one’s personal library is the pursuit of a lifetime. It requires special thought and consideration. Each book represents a piece of history, and it is a remarkable task to assemble these individual items into a collection. Our aim at Raptis Rare Books is to render tailored, individualized service to help you achieve your goals. We specialize in working with private collectors with a specific wish list, helping individuals find the ideal gift for special occasions, and partnering with representatives of institutions. We are here to assist you in your pursuit. Thank you for letting us be your guide in bringing the library of your imagination to reality. OUR GUARANTEE All items are fully guaranteed and can be returned within ten days. We accept all major credit cards and offer free domestic shipping and free worldwide shipping on orders over $500 for single item orders. A wide range of rushed shipping options are also available at cost. Each purchase is expertly packaged to ensure safe arrival and free gift wrapping services are available upon request. FOR MORE INFORMATION For further details regarding any of the items featured in these pages, visit our website or call 561-508-3479 for expert assistance from one of our booksellers. www.RaptisRareBooks.com Raptis Rare Books | 226 Worth Avenue | Palm Beach, FL 33480 T. 561-508-3479 | F. 561-757-7032 | [email protected] Presenting 80 Great Works Opening Selections 2 History & World Leaders 12 Americana 14 Scientific Discovery 28 Business & Economics 42 Literature 50 Children’s Literature 76 Index 81 Opening Selections RARE FIRST EDITION OF HERODOTUS’ HISTORIAE, IN GREEK HERODOTUS; EDITED BY ALDUS MANUTIUS Historiae, In Greek. -

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel. -

Library Collection 19-08-20 Changes-By-Category

Temple Sholom Library 8/20/2019 BOOK PUB TITLE AUTHOR FORMAT CATEGORY KEYWORDS DATE CALL NUMBER The Menorah Treasury: Harvest of Half a Century Writers, The Menorah Hardcover 6416760 1964 800 Sc Library Holocaust, Jewish (19391945) Poland Lódâz, Personal narratives The Boys Who Saved the Children Baldwin, Margaret Binding ¡âodâz Juvenile literature, Edelbaum, Ben, 1928 Juvenile literature, Jewish children in 1981 Je 940.4 Ba Bernstein Remembered Fluegel, Jane Hardcover 20th century music Bernstein, Leonard, 19181990 Portraits, Musicians Portraits, photographs 690.8 FL 1918: War and Peace Dallas, Gregor Hardcover 20th Century World History World War, 19141918 Peace, World War, 19141918 Armistices Mass Market Night Wiesel, Elie Paperback 4for3 Books : Biographies & Memoirs Elie Wiesel, Buchenwald, Holocaust, Auschwitz 1982 B Wi 4for3 Books : Children's Books : Baby Hanukkah Cat Burstein, Chaya M. Paperback Books Cats Fiction, Hanukkah Fiction 2001 J Bu 4for3 Books : Children's Books : Baby Musical books Specimens, Children's songs Texts, Dreidel (Game) Songs Dreidel, Dreidel, Dreidel Board Book Domain, Public Hardcover Books and music, Hanukkah Songs and music, Songs, Toy and movable books, 1998 J Dr 4for3 Books : Children's Books : Baby The Shapes of My Jewish Year (Very First Board Books) GoldVukson, Marji Hardcover Books Fasts and feasts Judaism Juvenile, literature, Shapes Juvenile literature 2003 J Go 4for3 Books : Children's Books : Baby Fasts and feasts Judaism Juvenile, literature, Sounds Juvenile literature, The Sounds of My Jewish Year (Very First Board Books) GoldVukson, Marji Board book Books Fasts and feasts Judaism, Holidays, Sound 2003 J Go 4for3 Books : Children's Books : Baby Light the Candles: A Hanukkah LifttheFlap Book (Picture Puffins) Holub, Joan Paperback Books Hanukkah Juvenile fiction 2000 J Ho 4for3 Books : Children's Books : Baby What Is God's Name? (Early Childhood Sprituality) Sasso, Sandy Eisenberg Board book Books God, spiritualitychildren 1999 J 136 Sa 4for3 Books : Children's Books : Baby Bible. -

Norman Cousins Papers, 1924-1991, Bulk 1944-1990

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft558004w3 No online items Finding Aid for the Norman Cousins papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Processed by Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Norman 1385 1 Cousins papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Finding Aid for the Norman Cousins Papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Collection number: 1385 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Contact Information Manuscripts Division UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Telephone: 310/825-4988 (10:00 a.m. - 4:45 p.m., Pacific Time) Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ Processed by: Manuscripts Division staff Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Text converted and initial container list EAD tagging in part by: Apex Data Services © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Norman Cousins papers, Date (inclusive): 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Collection number: 1385 Creator: Cousins, Norman. Extent: 1816 boxes (908 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. -

Worcester Historical

Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies 11 Hawthorne Street Worcester, Massachusetts ARCHIVES 2019.01 Kline Collection Processd by Casey Bush January 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Series Page Box Collection Information 3 Historical/Biographical Notes 4 Scope and Content 4 Series Description 5 1 Antisemitic Material 7-15 1-2, 13 2 Holocaust Material 16-22 2-3, 13 3 Book Jackets 23 4-9 4 Jewish History material 24-29 10-11, 13 5 Post-war Germany 30-32 12 6 The Second World War & Resistance 33-37 28 7 French Books 38-41 14 8 Miscellaneous-language materials 42-44 15 9 German language materials 45-71 16-27 10 Yiddish and Hebrew language materials 72-77 29-31 11 Immigration and Refugees 78-92 32-34 12 Oversized 93-98 35-47 13 Miscellaneous 99-103 48 14 Multi-media 104-107 49-50 Appendix 1 108 - 438 2 Collection Information Abstract : This collection contains books, pamphlets, magazines, guides, journals, newspapers, bulletins, memos, and screenplays related to anti-Semitism, German history, and the Holocaust. Items cover the years 1870-1990. Finding Aid : Finding Aid in print form is available in the Repository. Preferred Citation : Kline Collection – Courtesy of The Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts. Provenance : Purchased in 1997 from Eric Chaim Kline Bookseller (CA) through the generosity of the following donors: Michael J. Leffell ’81 and Lisa Klein Leffell ’82, the Sheftel Family in memory of Milton S. Sheftel ’31, ’32 and the proceeds of the Carole and Michael Friedman Book Fund in honor of Elisabeth “Lisa” Friedman of the Class of 1985.