1 Leviathan and Its Intellectual Context Kinch Hoekstra Scholars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bartow-Pell: a Family Legacy

Lesson Plan: Bartow-Pell: A Family Legacy Architect: Minard Lafever, with John Bolton, local carpenter, both friends of the Bartow family. Site: Bartow-Pell Mansion Curriculum Link: High School US History and Government (this is a review activity that brings together several units of study) Unit Two: A:2:a and c The peoples and peopling of the American colonies (voluntary and involuntary)—Native American Indians (relations between colonists and Native American Indians, trade, alliances, forced labor, warfare) and Varieties of immigrant motivation, ethnicities, and experiences. A:4 The Revolutionary War and the Declaration of Independence D:1 The Constitution in jeopardy: The American Civil War 7th and 8th Grade Social Studies I. European Exploration and Settlement D. Exploration and settlement of the New York State area by the Dutch and English 1. Relationships between the colonists and the Native American Indians 4. Rivalry between the Dutch and English eventually resulting in English supremacy Project Aim: Through an investigation of the long history of the Bartow-Pell estate, students discover the far-reaching influence of this family in American history throughout their long occupation of this property. Students will also be able to contextualize history as a series of events that are caused by and effect the lives of real people. Students will be able to imagine the great events of American history through the lens of a family local to the Bronx. Vocabulary: Greek Revival: A style of art that was popular in the 19th Century that was a reaction to Baroque Art. This style was derived from the art and culture of ancient Greece and imitated this period’s architecture and fascination for order and simplicity. -

William Hamilton Merritt and Pell's Canal.FH11

Looking back... with Alun Hughes WILLIAM HAMILTON MERRITT AND PELLS CANAL It is not entirely clear when William Hamilton March he wrote to his wife that The waters of Merritt first had the idea of building a canal between Chippawa Creek will be down the 12 in two years Lakes Erie and Ontario. According to his son and from this time as certain as fate. Later that month biographer Jedediah, it was while he was patrolling he held a preliminary meeting at Shipmans Tavern, the Niagara River during the War of 1812, but and in April a subscription was opened to pay for a Merritt himself recalled late in life that the idea came professional survey of the canal route, which took to him after the war when water-supply problems place in May. In June a public meeting was held at plagued his milling operations on the Twelve Mile Beaverdams, and in July Merritt and eight others Creek. The solution he envisaged a supply announced their intention to apply to the Legislature channel to carry water from the Welland River (or for incorporation of what became the Welland Canal Chippawa Creek) into the headwaters of the Twelve Company. The required act was passed in January soon evolved into a canal to carry barge traffic. 1824, and construction began that November. In 1817 Merritt presented the case for a canal as part of Grantham Townships response to Robert Gourlay One authority suggests that the answer to the for this Statistical Account of Upper Canada, and mystery of Pells Canal lies in Chautauqua, in a in September 1818, with the help of others, he used proposal made around 1800 to replace the ancient a borrowed water level to survey the rise of land portage road between Lake Erie and Chautauqua between the two creeks to assess the ideas feasibilty. -

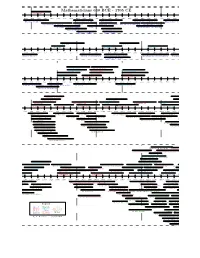

Mathematicians Timeline

Rikitar¯oFujisawa Otto Hesse Kunihiko Kodaira Friedrich Shottky Viktor Bunyakovsky Pavel Aleksandrov Hermann Schwarz Mikhail Ostrogradsky Alexey Krylov Heinrich Martin Weber Nikolai Lobachevsky David Hilbert Paul Bachmann Felix Klein Rudolf Lipschitz Gottlob Frege G Perelman Elwin Bruno Christoffel Max Noether Sergei Novikov Heinrich Eduard Heine Paul Bernays Richard Dedekind Yuri Manin Carl Borchardt Ivan Lappo-Danilevskii Georg F B Riemann Emmy Noether Vladimir Arnold Sergey Bernstein Gotthold Eisenstein Edmund Landau Issai Schur Leoplod Kronecker Paul Halmos Hermann Minkowski Hermann von Helmholtz Paul Erd}os Rikitar¯oFujisawa Otto Hesse Kunihiko Kodaira Vladimir Steklov Karl Weierstrass Kurt G¨odel Friedrich Shottky Viktor Bunyakovsky Pavel Aleksandrov Andrei Markov Ernst Eduard Kummer Alexander Grothendieck Hermann Schwarz Mikhail Ostrogradsky Alexey Krylov Sofia Kovalevskya Andrey Kolmogorov Moritz Stern Friedrich Hirzebruch Heinrich Martin Weber Nikolai Lobachevsky David Hilbert Georg Cantor Carl Goldschmidt Ferdinand von Lindemann Paul Bachmann Felix Klein Pafnuti Chebyshev Oscar Zariski Carl Gustav Jacobi F Georg Frobenius Peter Lax Rudolf Lipschitz Gottlob Frege G Perelman Solomon Lefschetz Julius Pl¨ucker Hermann Weyl Elwin Bruno Christoffel Max Noether Sergei Novikov Karl von Staudt Eugene Wigner Martin Ohm Emil Artin Heinrich Eduard Heine Paul Bernays Richard Dedekind Yuri Manin 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 Carl Borchardt Ivan Lappo-Danilevskii Georg F B Riemann Emmy Noether Vladimir Arnold August Ferdinand -

Introduction Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Was One of the Most Prolific Thinkers

Chapter 1: Introduction “Theoria cum praxi [Theory with practice]”—Leibniz’s motto for the Berlin Society of Sciences. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was one of the most prolific thinkers of all time. “Often in the morning when I am still in bed,” he wrote, “so many thoughts occur to me in a single hour that sometimes it takes me a whole day or more to write them out” (LH 338; quoted from Mates 1986, 34). These thoughts might have included designs for a new wind pump to drain the mines of the Harz mountains or for a calculating machine based on binary arithmetic, sketches for a treatise on geology or etymology, another draft of a logical calculus that was two hundred years ahead of its time, or a new derivation of Newton’s law of gravitation on strictly mechanical principles. Even before getting up, Leibniz would usually have written lengthy letters on such subjects to one or two learned correspondents, and perhaps a proposal to Peter the Great for a scientific academy, or to his employer the Duke of Hanover for a universally accessible state medical system. He might have penned a legal brief in support of the Duke’s electoral claim to certain territories, a deposition aimed at church reunification, or tried to mediate in the dispute among the Jesuits over the interpretation of Chinese religious rites. In short, Leibniz was an indefatigable one-man industry. Yet all this worldly activity seems at odds with the usual understanding of Leibniz as a philosopher. He is well known for his claim that the world is constituted by what he calls monads (or unities), which he characterizes as substances consisting in perceptions (representations of the whole of the rest of the universe) and appetitions (tendencies toward future states), governed by a law specific to each individual. -

Chapter Four Pay-Ing for Pansophy , 'The Pansophical Vndertaking Is Of

230 PART YWO: WISDCW - Chapter Four Pay-Ing for Pansophy ,'The Pansophical Vndertaking is of mighty importance. For what can bee almost greater then to have All knowledge. If it were with the addition to have All love also it were perfection' - Joachim HQbner, cited in Ephemerides 1639, HP 30/4/12A. 4: 1 origins of the Pansophic Project From Moriaen's first surviving letter to Hartlib, it is evident that when he arrived in Amsterdam he was already deeply, indeed missionarily, committed to his friend's project to fund and publicise Pansophy, the vision of universal wisdom whose most famous formulation was being worked out by the Moravian theologian and 1 pedagogue Jan Amos Komensky, or Comenius. This scheme 1 The secondary literature on Comenius is enormous. The fullest biographical account is Milada Blekastad's Comenius: Versuch eines Umrisses von Leben Werk und Schicksal des Jan Amos Komensky (Oslo and Prague, 1969), which despite its modest title is a detailed and exhaustive account of his life and work, based heavily and usefully (though at times somewhat uncritically) on Comenius's correspondence and autobiographical writings. Still valuable are the many studies written nearly a century ago by Jan Kva6ala, particularly Die Padagogische Reform des Comenius in Deutschland bis zum Ausgange des xvIX Jahrhunderts (Monumenta Germaniae P&udagogica XVII (Berlin,, 1903) and XXII (Berlin, 1904)). The standard English sources are Turnbull, HDC part 3 (342-464), Webster, Great Xnstauration and 'Introduction' to Samuel Hartlib and the Advancement of Learning (Cambridge, 1970), and Hugh Trevor-Roper's rather dismissive and anglocentric 'Three Foreigners: The Philosophers of the Puritan Revolution', in Religion, the Reformation and social change (London, 1967), 237-293 (on Hartlib, Dury and Comenius and their impact in England). -

The Mathematical Minister: John Wallis (1616-1703) at the Intersection of Science, Mathematics, and Religion

The Mathematical Minister: John Wallis (1616-1703) at the Intersection of Science, Mathematics, and Religion by Adam Richter A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Adam Richter 2018 The Mathematical Minister: John Wallis (1616-1703) at the Intersection of Science, Mathematics, and Religion Adam Richter Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2018 Abstract John Wallis, Savilian Professor of Geometry at Oxford, is primarily known for his contributions to seventeenth-century mathematics. However, as a founder member of the Royal Society and an Anglican minister, Wallis also had a productive career in both natural philosophy and theology. This thesis considers Wallis as a “clerical practitioner” of science—a member of the clergy who studied natural philosophy as well as divinity—and seeks to articulate his unique perspective on the relationship between God and nature. This account of Wallis serves as a case study in the history of science and religion, establishing several novel connections between secular and sacred studies in seventeenth-century England. In particular, Wallis blends elements of experimental philosophy, Calvinist theology, and Scholastic philosophy in creative ways to make connections between the natural and the divine. This thesis has three main goals. First, it traces Wallis’s unique and idiosyncratic role in the history of science and religion. Second, it complicates two common narratives about Wallis: first, that he is historically significant mostly because his mathematics served as a precursor to Isaac Newton’s development of calculus, and second, that his successful career is the result of his ambition and political savvy rather than his original contributions to mathematics, natural philosophy, theology, and other fields. -

The Relation Between Leibniz and Wallis: an Overview from New Sources and Studies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UPCommons. Portal del coneixement obert de la UPC Quaderns d’Història de l’Enginyeria volum xvi 2018 THE RELATION BETWEEN LEIBNIZ AND WALLIS: AN OVERVIEW FROM NEW SOURCES AND STUDIES Siegmund Probst [email protected] In memoriam Walter S. Contro (1937-2017) In 2016 the 400th anniversaries of the death of Cervantes and of Shakespeare were commemorated throughout the world. But the same year is also impor- tant in the history of mathematics as the year of the 400th anniversary of the birth of John Wallis (1616-1703) and the year of the 300th anniversary of the death of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716). Separated by a generation, there was a mutual reception and discussion of the two scholars which com- prises a period of more than 30 years in their lives and deals with a variety of scientific, especially mathematical topics, and some other fields of scholarly discussion, too. The exchange between them was first started by the corre- spondence Leibniz entered with Henry Oldenburg (1618-1677), the secretary of the Royal Society. But Wallis and Leibniz never met in person: When Leibniz visited London early in 1673 and in October 1676 and met Oldenburg, Robert Boyle (1627-1692), John Pell (1610-1685), and other members of the Royal Society, Wallis was not present, and the same holds for Isaac Newton (1643-1727). A direct correspondence between them was started only in 1695 by Leibniz, but as is clear from their letters and other writings, they read each other’s publications carefully, and Leibniz even wrote reviews of books published by Wallis. -

'My Friend the Gazetier': Diplomacy and News in Seventeenth

chapter 18 ‘My Friend the Gazetier’: Diplomacy and News in Seventeenth-Century Europe Jason Peacey In February 1681, the English government was hunting for information about European newspapers. Its new envoy at The Hague, Thomas Plott, duly obliged by writing that “The printed paper of Leyden … I have never seen”, although he had heard that “such a paper had appeared”, and that “it had been suppressed”. That he knew this much reflected the fact that he had already made a point of getting to know “the French gazetier, who is my friend”, and who had previ- ously been a “pensionary” of the English ambassador, Henry Sidney. Indeed, Plott also added that “what news he has he always communicates to me in a manuscript, but when there is nothing worth writing he only supplies me with his gazettes, so that what intelligence he had, I can always furnish you with”. Plott concluded by adding that I have likewise another intelligencer here who is paid for it, that gives me twice a week what comes to his hands, whose original papers and likewise those of the French gazetier I shall hereafter send you, and when I return for England I shall settle a correspondence between you and them, that you may have a continuance of their news.1 That Plott’s first tasks upon reaching The Hague had included familiarising himself with European print culture, its gazetteers and its intelligencers is highly revealing, and the aim of this piece is explore the significance of this letter, and of the practices to which it alludes. -

Samuel H. and Mary T. Booth House

DESIGNATION REPORT Samuel H. and Mary T. Booth House Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 502 Commission Booth House LP-2488 November 28, 2017 DESIGNATION REPORT Samuel H. and Mary T. Booth House LOCATION Borough of the Bronx 30 Centre Street, City Island LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE A wood frame house designed in the Stick style and constructed between 1887 and 1893, which is representative of the 19th-century development of City Island. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 502 Commission Booth House LP-2488 November 28, 2017 Samuel H. and Mary T. Booth House (LPC) 2017 (above) 30 Centre Street, New York City Tax photo, c. 1940, NYC Municipal Archives (left) Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 502 Commission Booth House LP-2488 November 28, 2017 3 of 17 Samuel H. and Mary T. Booth Revival and Queen Anne styles. Samuel Booth moved his family to City Island by 1880 where he House established his career as a carpenter and house 30 Centre Street, the Bronx builder. The Booth family owned the house at 30 Centre Street until 1959 during which time they added a rear porch, a gabled oriel on the east and an angled bay on the west. The house remained unchanged until new owners renovated it in the late- 20th or early-21st century, building out the attic on Designation List 502 two sides, reconfiguring the attic windows, replacing LP-2488 the first-story windows on the east with a bay window, and replacing some of the historic Built: c. 1887-1893 clapboard with decorative shingles. -

History of Mathematics: 17Th and 18Th Century Mathematicians 2007 National Mu Alpha Theta Convention NOTA Means “None of the Above”

History of Mathematics: 17th and 18th Century Mathematicians 2007 National Mu Alpha Theta Convention NOTA means “None of the Above” 1. This famous mathematician was banned from his family’s home after winning the Paris Academy Award jointly with his father. It is rumored that his father stole one of his great discoveries, changed the name and date on it, and claimed it as his own. One of his discoveries was on the conservation of energy. A. Jacob Bernoulli B. Johann Bernoulli II C. Daniel Bernoulli D. Nicolaus Bernoulli E. NOTA 2. This man’s father was a leather merchant. He married his mother’s cousin and had 3 sons and 2 daughters. He had a wide knowledge of European literature and languages. He worked as a king’s councilor and was expected to hold himself aloof from townsmen to abstain from unnecessary social activities so not to be corrupted by bribery. He was the first to apply analytic geometry to three dimensions. A. Pierre Fermat B. Blaise Pascal C. John Wallis D. Rene Descartes E. NOTA 3. This mathematician is commonly referred to as, “The Greatest Might Have Been in History”. His father banned mathematics in their household because he thought his son might overstrain. His sister bragged to other mathematicians that he discovered the first 32 propositions from Geometry as Euclid, and even in the same order! He suffered from Acute Dyspepsia and Insomnia until he died at age 39. A. James Gregory B. Blaise Pascal C. John Wallis D. Sir Christopher Wren E. NOTA 4. This lucky guy was a senator to Napoleon, Count of the Empire, and Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor. -

2440 Eblj Article 6, 2007

A Fragment of the Library of Theodore Haak (1605-1690) William Poole Great libraries are often built on the stock of prior great libraries, as much in the early modern period as in others. As the seventeenth-century French librarian Gabriel Naudé counselled his budding collector, ‘the first, the speediest, easie and advantagious [way] of all the rest ... is made by the acquisition of some other entire and undissipated Library.’1 One of the more valuable pleasures of provenance research is the detection of such libraries- behind-libraries, often extending to two, three, or even more removes. Over time, however, many collections assembled upon earlier collections suffer mutilation, and this mutilation inevitably disturbs the older strata. One example relevant to this article is the library of the Royal Society of London: when this library was a mere toddler, it was joined in 1667 by the distinctly aristocratic Arundelian library; later, these collections effectively merged. Behind Thomas Howard, Fourteenth Earl of Arundel’s, great Caroline library lay the bulk of the German humanist Willibald Pirckheimer’s collection; and at the centre of Pirckheimer’s collection was a supposed third of the books of the fifteenth-century King of Hungary Matthias Corvinus. But even in its earliest days the archaeology of the Royal Society’s ‘Bibliotheca Norfolciana’ may not have been appreciated by its new custodians. As the FRS and mathematician John Pell (1611-1685) wrote in March 1667 on the Society’s new library to the subject of this article, Theodore Haak (1605-1690), ‘I beleeve, divers of the R. S. -

Christiaan Huygens

CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS (April 14, 1629 – July 8, 1695) by HEINZ KLAUS STRICK, Germany Born in the Hague as the son of a poet and wealthy diplomat, CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS enjoyed extensive and varied training from various private tutors. In addition to Latin, Greek, French and Italian, he also learnt arithmetic, logic, geography and composition. His father CONSTANTIN HUYGENS had connections with many important scientists all over Europe, not least due to his work on behalf of WILHELM II, PRINCE OF ORANGE, the governor of the young Republic of the Netherlands. One of the friends of the family was RENÉ DESCARTES (1596 – 1650), who had lived in liberal Holland since 1629. (drawing: © Andreas Strick) At the age of 16, CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS began studying law in Leiden, and attended mathematics lectures by FRANS VON SCHOOTEN (1615 – 1660), a gifted teacher of mathematics and editor of FRANÇOIS VIÈTE's (1540 – 1603) Opera mathematica. He then moved to Breda, where JOHN PELL (1611 – 1685) taught, and received his doctorate in law at the Protestant University of Angers. Contrary to family tradition, he did not enter the diplomatic service but devoted himself to scientific research. In his first publication, published in 1651, he dealt with the determination of tangents to curves and the centres of gravity of surfaces. He also proved that a squaring of the circle by the Flemish mathematician GRÉGOIRE DE SAINT-VINCENT, published in 1647, was faulty. With this reputation, HUYGENS set off on a journey to Paris in 1655. There he heard about the famous correspondence between PIERRE DE FERMAT (1608 – 1665) and BLAISE PASCAL (1623 – 1662) from 1654, but found out nothing about its contents: ..