Robert-Hooke-And-Westminster.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tale of a Fish How Westminster Abbey Became a Royal Peculiar

The Tale of a Fish How Westminster Abbey became a Royal Peculiar For Edric it had been a bad week’s fishing in the Thames for salmon and an even worse Sunday, a day on which he knew ought not to have been working but needs must. The wind and the rain howled across the river from the far banks of that dreadful and wild isle called Thorney with some justification. The little monastic church recently built on the orders of King Sebert stood forlornly waiting to be consecrated the next day by Bishop Mellitus, the first Bishop of London, who would be travelling west from the great Minster of St Paul’s in the City of London. As he drew in his empty nets and rowed to the southern bank he saw an old man dressed in strange and foreign clothing hailing him. Would Edric take him across even at this late hour to Thorney Island? Hopeful for some reward, Edric rowed across the river, moaning to the old man about the poor fishing he had suffered and received some sympathy as the old man seemed to have had some experience in the same trade. After the old man had alighted and entered the little church, suddenly the building was ablaze with dazzling lights and Edric heard chanting and singing and saw a ladder of angels leading from the sky to the ground. Edric was transfixed. Then there was silence and darkness. The old man returned and admonished Edric for fishing on a Sunday but said that if he caste his nets again the next day into the river his reward would be great. -

Westminster City Council

Westminster Your choice for secondary education A guide for parents with children transferring to secondary school in 2019 APPLY ONLINE FOR YOUR CHILD’S SECONDARY SCHOOL PLACE westminster.gov.uk/admissions Westminster City Council westminster.gov.uk APPLY ONLINE AND SAVE TIME CONTENTS The Pan-London eAdmissions site opens on 1st September 2018. CONTACTING THE ADMISSIONS TEAM 4 SCHOOL INFORMATION 21 If your child was born between 1st September Common definitions 21 2007 and 31st August 2008, you will need to INTRODUCTION TO WESTMINSTER’S The Grey Coat Hospital 22 apply for a secondary school place by SECONDARY SCHOOLS 5 31st October 2018. Harris Academy St. John’s Wood 26 Applying online can be done in five easy steps. PAN-LONDON SYSTEM 5 Marylebone Boys’ School 28 How the system works 5 Paddington Academy 30 Why apply online? Pimlico Academy 32 • It is quick and easy to do. KEY DATES 6 St. Augustine’s CE High School 34 • It’s more flexible as you can change or delete preferences on your application up until St. George’s Catholic School 38 GATHERING INFORMATION 7 the application deadline of 11.59pm on The St. Marylebone CE School 40 31st October 2018. Considering the facts 7 Westminster Academy 44 • You’ll receive an email confirmation once Applying for schools outside Westminster 8 you submit the application. Westminster City School 46 • You can receive reminder alerts to your mobile THE APPLICATION PROCESS 9 to make sure your application gets in on time. ALL-THROUGH SCHOOL (4–18) 50 Closing date for applications 9 • You will receive your outcome by email Ark King Solomon Academy 50 Proof of address 9 during the evening of 1st March 2019. -

John Dryden and the Late 17Th Century Dramatic Experience Lecture 16 (C) by Asher Ashkar Gohar 1 Credit Hr

JOHN DRYDEN AND THE LATE 17TH CENTURY DRAMATIC EXPERIENCE LECTURE 16 (C) BY ASHER ASHKAR GOHAR 1 CREDIT HR. JOHN DRYDEN (1631 – 1700) HIS LIFE: John Dryden was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who was made England's first Poet Laureate in 1668. He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the “Age of Dryden”. The son of a country gentleman, Dryden grew up in the country. When he was 11 years old the Civil War broke out. Both his father’s and mother’s families sided with Parliament against the king, but Dryden’s own sympathies in his youth are unknown. About 1644 Dryden was admitted to Westminster School, where he received a predominantly classical education under the celebrated Richard Busby. His easy and lifelong familiarity with classical literature begun at Westminster later resulted in idiomatic English translations. In 1650 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he took his B.A. degree in 1654. What Dryden did between leaving the university in 1654 and the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 is not known with certainty. In 1659 his contribution to a memorial volume for Oliver Cromwell marked him as a poet worth watching. His “heroic stanzas” were mature, considered, sonorous, and sprinkled with those classical and scientific allusions that characterized his later verse. This kind of public poetry was always one of the things Dryden did best. On December 1, 1663, he married Elizabeth Howard, the youngest daughter of Thomas Howard, 1st earl of Berkshire. -

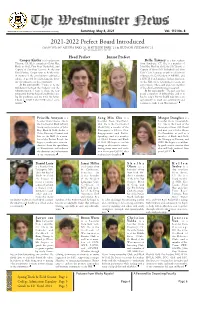

2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced - - - Times

Westminster School Simsbury, CT 06070 www.westminster-school.org Saturday, May 8, 2021 Vol. 110 No. 8 2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced COMPILED BY ALEYNA BAKI ‘21, MATTHEW PARK ‘21 & HUDSON STEDMAN ‘21 CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF, 2020-2021 Head Prefect Junior Prefect Cooper Kistler is a boarder from Bella Tawney is a day student Tiburon, CA. He is a member of John Hay, from Simsbury, CT. She is a member of Black & Gold, First Boys’ Basketball, and John Hay, Black & Gold, the SAC Board, a Captain of First Boys’ lacrosse. As the new Captain of First Girls’ Basketball and First Head Prefect, Cooper aims to be the voice Girls’ Cross Country, as well as a Horizons of everyone in the community to cultivate a volunteer, the Co-President of AWARE, and culture of growth by celebrating the diver- a HOTH board member. In her final year sity of perspectives in the community. on the Hill, she is determined to create an In his own words: “I want to be the environment, where each and every member middleman between the Students and the of the school community feels accepted. Administration. I want to share the new In her own words: “The past year has perspective that we have all established dur- posed a number of difficulties, and it is ing the pandemic, and use it for the better. hard to adapt, but we should take this as an I want to UNITE the NEW school com- opportunity to teach our community and munity." continue to make it our Westminster." Priscilla Ameyaw is a Sung Min Cho is a Margot Douglass is a boarder from Ghana. -

014 Westminster Abbey 013 Royal Opera House

disabled toilets in various locations, including next to the main entrance and by the 013 Royal Opera House Amphitheatre bar. All operas come with surtitles, and some performances have BSL interpretation. In addition, there are special headphones available to amplify the sound, Address: Covent Garden, London WC2E 9DD Web: www.roh.org.uk Tel: switchboard: 020 7240 and an induction collar to be used with hearing aids. It’s worth noting that the ROH L 1200, box o"ce: 020 7304 4000 Hours: box o"ce Mon–Sat 10am–8pm, Sun 2–4 hours before o$ers a free Access Membership Scheme (allow three weeks for registration), which L ONDON ONDON performances; ROH Collections open Mon–Fri 10am–3.30pm (performance ticket holders only) Dates: includes several bene!ts including discounted tickets, priority booking, personalised closed 25 Dec & Easter Sunday Entry: varies by performance and seat [D]25% discount when registered assistance and same-day telephone booking. to ROH’s free Access Membership Scheme [C]free if accompanying disabled scheme member [0–18s] ĪĪ at selected “family” performances 2 children go free with paying adult, otherwise same rate as adults FOOD & DRINK "ere are several well-appointed on-site bars and restaurants. !e Paul [Con]half-price standby tickets, subject to availability (see website for details); see below for tour prices Hamlyn Hall Balconies Restaurant o$ers an especially memorable setting, overlooking the Floral Hall – with prices to match, of course (two courses for £42.50; three courses £49.50). Commanding a prime spot in London’s picturesque Covent Garden, the Royal Opera House 014 Westminster Abbey is the capital’s premier opera venue and the home of the Royal Ballet and Royal Opera. -

Katharine and Philip Henry and Their Children: a Case Study in Family Ideology

KATHARINE AND PHILIP HENRY AND THEIR CHILDREN: A CASE STUDY IN FAMILY IDEOLOGY. Patricia Crawford, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. Historians are currently debating the nature of English families in the early modern period. In his ambitious study of the family from 1500 1800, Lawrence Stone has argued that there was a transition from families in which there was little love between spouses, little affection between parents and children, to ones in which love was important. 1 His critics have argued that the picuture is not so black as he has painted, and in the most recent study of the English family over a similar period of time, Ralph Houlbrooke has rejected Stone's depiction of change and argued rather for continuity of patterns of affection.2 There is a danger in the geneal discussion at present that by focussing on questions about the degree of happiness within families, to which ultimately there can be no answers, historians will be diverted from the more important questions about the ways in which ideas influ enced the lives of men and women in the past, and how the family transmitted values from one generation to another. In particular, the family taught children their place in the world: their social position and their gender. Yet, what we know of individual families and their dynamics in the early modern period is still fairly limited. Alan Macfarlane's pioneering study of the Essex clergyman, Ralph Josselin, is deservedly widely cited, but we still need further studies to allow us to assess whether Josselin was a typical or unusual individual.3 Miriam Slater has assessed Stone's general conclusions through the records of one upper gentry family, the Verneys, and Vivienne Larminie has concluded, from her study of another gentry family, the Newdigates, that the personalities of individuals influenced the effects of patriarchal ideas in families.' It is only on such detailed studies that the broad generalisations can rest. -

A Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

252 CATALOGUE OF MANUSCRIPTS [114 114. PARKER'S CORRESPONDENCE. \ ~, ' [ L . jT ames vac. Codex chartaceus in folio, cui titulus, EPISTOL^E PRINCIPUM. In eo autem continentur, 1. Epistola papae Julii II, ad Henricum VIII. in qua regem orat ut eum et sedem apostolicam contra inimicos defendat, data 14 Martii 1512, p. 4. 2. Henry VIII's recommendatory letter for Dr. Parker to be master of Corpus Christi College, dated Westminster ultimo Nov. anno regni 36°. original, p. 5. 3. Letter from queen Katherine [Parr] recommending Randall Radclyff to the bayliwick of the college of Stoke, dated Westm. 14 Nov. 36 Hen. VIII. p. 7. 4. Warrant for a doe out of the forest of Wayebrige under the sign manual of Henry VIII. dated Salisbury Oct. 13, anno regni 36, p. 8. 5. Letter from queen Elizabeth to the archbishop directing him to receive and entertain the French ambassador in his way to London. Richmond May 14, anno regni 6*°. p. 13. 6. From the same, commanding the archbishop to give his orders for a general prayer and fasting during the time of sickness, and requiring obedience from all her subjects to his directions, dated Richmond Aug. I, anno regni 5*°. p. 15. 7. From the same, directing the archbishop and other commissioners to visit Eaton-college, and to enquire into the late election of a provost, dated Lea 22 Aug. anno regni 3*°. p. 21. 8. Visitatio collegii de Eaton per Mattheum Parker archiepiscopum Cantuariensem, Robertum Home episcopum Winton et Anthonium Cooke militem, facta 9, 10 et 11 Sept. 1561, p. -

Bartow-Pell: a Family Legacy

Lesson Plan: Bartow-Pell: A Family Legacy Architect: Minard Lafever, with John Bolton, local carpenter, both friends of the Bartow family. Site: Bartow-Pell Mansion Curriculum Link: High School US History and Government (this is a review activity that brings together several units of study) Unit Two: A:2:a and c The peoples and peopling of the American colonies (voluntary and involuntary)—Native American Indians (relations between colonists and Native American Indians, trade, alliances, forced labor, warfare) and Varieties of immigrant motivation, ethnicities, and experiences. A:4 The Revolutionary War and the Declaration of Independence D:1 The Constitution in jeopardy: The American Civil War 7th and 8th Grade Social Studies I. European Exploration and Settlement D. Exploration and settlement of the New York State area by the Dutch and English 1. Relationships between the colonists and the Native American Indians 4. Rivalry between the Dutch and English eventually resulting in English supremacy Project Aim: Through an investigation of the long history of the Bartow-Pell estate, students discover the far-reaching influence of this family in American history throughout their long occupation of this property. Students will also be able to contextualize history as a series of events that are caused by and effect the lives of real people. Students will be able to imagine the great events of American history through the lens of a family local to the Bronx. Vocabulary: Greek Revival: A style of art that was popular in the 19th Century that was a reaction to Baroque Art. This style was derived from the art and culture of ancient Greece and imitated this period’s architecture and fascination for order and simplicity. -

Commander Ship Port Tons Mate Gunner Boatswain Carpenter Cook

www.1812privateers.org ©Michael Dun Commander Ship Port Tons Mate Gunner Boatswain Carpenter Cook Surgeon William Auld Dalmarnock Glasgow 315 John Auld Robert Miller Peter Johnston Donald Smith Robert Paton William McAlpin Robert McGeorge Diana Glasgow 305 John Dal ? Henry Moss William Long John Birch Henry Jukes William Morgan William Abrams Dunlop Glasgow 331 David Hogg John Williams John Simpson William James John Nelson - Duncan Grey Eclipse Glasgow 263 James Foulke Martin Lawrence Joseph Kelly John Kerr Robert Moss - John Barr Cumming Edward Glasgow 236 John Jenkins James Lee Richard Wiles Thomas Long James Anderson William Bridger Alexander Hardie Emperor Alexander Glasgow 327 John Jones William Jones John Thomas William Thomas James Williams James Thomas Thomas Pollock Lousia Glasgow 324 Alexander McLauren Robert Caldwell Solomon Piike John Duncan James Caldwell none John Bald Maria Glasgow 309 Charles Nelson James Cotton? John George Thomas Wood William Lamb Richard Smith James Bogg Monarch Glasgow 375 Archibald Stewart Thomas Boutfield William Dial Lachlan McLean Donald Docherty none George Bell Bellona Greenock 361 James Wise Thomas Jones Alexander Wigley Philip Johnson Richard Dixon Thomas Dacers Daniel McLarty Caesar Greenock 432 Mathew Simpson John Thomson William Wilson Archibald Stewart Donald McKechnie William Lee Thomas Boag Caledonia Greenock 623 Thomas Wills James Barnes Richard Lee George Hunt William Richards Charles Bailey William Atholl Defiance Greenock 346 James McCullum Francis Duffin John Senston Robert Beck -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

The King James Bible

Chap. iiii. The Coming Forth of the King James Bible Lincoln H. Blumell and David M. Whitchurch hen Queen Elizabeth I died on March 24, 1603, she left behind a nation rife with religious tensions.1 The queen had managed to govern for a lengthy period of almost half a century, during which time England had become a genuine international power, in part due to the stabil- ity Elizabeth’s reign afforded. YetE lizabeth’s preference for Protestantism over Catholicism frequently put her and her country in a very precarious situation.2 She had come to power in November 1558 in the aftermath of the disastrous rule of Mary I, who had sought to repair the relation- ship with Rome that her father, King Henry VIII, had effectively severed with his founding of the Church of England in 1532. As part of Mary’s pro-Catholic policies, she initiated a series of persecutions against various Protestants and other notable religious reformers in England that cumu- latively resulted in the deaths of about three hundred individuals, which subsequently earned her the nickname “Bloody Mary.”3 John Rogers, friend of William Tyndale and publisher of the Thomas Matthew Bible, was the first of her victims. For the most part, Elizabeth was able to maintain re- ligious stability for much of her reign through a couple of compromises that offered something to both Protestants and Catholics alike, or so she thought.4 However, notwithstanding her best efforts, she could not satisfy both groups. Toward the end of her life, with the emergence of Puritanism, there was a growing sense among select quarters of Protestant society Lincoln H. -

Ordination Sermons: a Bibliography1

Ordination Sermons: A Bibliography1 Aikman, J. Logan. The Waiting Islands an Address to the Rev. George Alexander Tuner, M.B., C.M. on His Ordination as a Missionary to Samoa. Glasgow: George Gallie.. [etc.], 1868. CCC. The Waiting Islands an Address to the Rev. George Alexander Tuner, M.B., C.M. on His Ordination as a Missionary to Samoa. Glasgow: George Gallie.. [etc.], 1868. Aitken, James. The Church of the Living God Sermon and Charge at an Ordination of Ruling Elders, 22nd June 1884. Edinburgh: Robert Somerville.. [etc.], 1884. Allen, William. The Minister's Warfare and Weapons a Sermon Preached at the Installation of Rev. Seneca White at Wiscasset, April 18, 1832. Brunswick [Me.]: Press of Joseph Grif- fin, 1832. Allen, Willoughby C. The Christian Hope. London: John Murray, 1917. Ames, William, Dan Taylor, William Thompson, of Boston, and Benjamin. Worship. The Re- spective Duties of Ministers and People Briefly Explained and Enforced the Substance of Two Discourses, Delivered at Great-Yarmouth, in Norfolk, Jan. 9th, 1775, at the Ordina- tion of the Rev. Mr. Benjamin Worship, to the Pastoral Office. Leeds: Printed by Griffith Wright, 1775. Another brother. A Sermon Preach't at a Publick Ordination in a Country Congregation, on Acts XIII. 2, 3. Together with an Exhortation to the Minister and People. London: Printed for John Lawrance.., 1697. Appleton, Nathaniel, and American Imprint Collection (Library of Congress). How God Wills the Salvation of All Men, and Their Coming to the Knowledge of the Truth as the Means Thereof Illustrated in a Sermon from I Tim. II, 4 Preached in Boston, March 27, 1753 at the Ordination of the Rev.